Homeless Negotiations of Public Space in Two California Cities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hoovervilles: the Shantytowns of the Great Depression by History.Com, Adapted by Newsela Staff on 04.04.17 Word Count 702 Level 830L

Hoovervilles: The Shantytowns of the Great Depression By History.com, adapted by Newsela staff on 04.04.17 Word Count 702 Level 830L A typical shantytown of the Great Depression in the United States, this one located in a city. Photo: WPA The Great Depression was an economic crisis that began in 1929. Many people had invested money in the stock market and when it crashed they lost much of the money they had invested. People stopped spending money and investing. Banks did not have enough money, which led many people to lose their savings. Many Americans lost money, their homes and their jobs. Homeless Americans began to build their own camps on the edges of cities, where they lived in shacks and other crude shelters. These areas were known as shantytowns. As the Depression got worse, many Americans asked the U.S. government for help. When the government failed to provide relief, the people blamed President Herbert Hoover for their poverty. The shantytowns became known as Hoovervilles. In 1932, Hoover lost the presidential election to Franklin Roosevelt. Roosevelt created programs that helped lift the U.S. out of the Depression. By the early 1940s, most remaining Hoovervilles were torn down. This article is available at 5 reading levels at https://newsela.com. 1 The Great Depression sets in The Great Depression was one of the most terrible events of the 1900s, and led to a huge rise in unemployment. By 1933, 1 out of 4 Americans was out of work. Americans looked to the U.S. government for help. -

American Identity, Humanitarian Experience, and the Commission for Relief in Belgium, 1914-1917 Thomas D

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 7-21-2014 Rough and Ready Relief: American Identity, Humanitarian Experience, and the Commission for Relief in Belgium, 1914-1917 Thomas D. Westerman University of Connecticut, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Westerman, Thomas D., "Rough and Ready Relief: American Identity, Humanitarian Experience, and the Commission for Relief in Belgium, 1914-1917" (2014). Doctoral Dissertations. 466. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/466 Rough and Ready Relief: American Identity, Humanitarian Experience, and the Commission for Relief in Belgium, 1914-1917 Thomas David Westerman, Ph.D. University of Connecticut, 2014 This dissertation examines a group of American men who adopted and adapted notions of American power for humanitarian ends in German-occupied Belgium with the Commission for Relief in Belgium (CRB) during World War I. The CRB, led by Herbert Hoover, controlled the importation of relief goods and provided supervision of the Belgian-led relief distribution. The young, college-educated American men who volunteered for this relief work between 1914 and 1917 constructed an effective and efficient humanitarian space for themselves by drawing not only on the power of their neutral American citizenship, but on their collectively understood American-ness as able, active, yet responsible young men serving abroad, thereby developing an alternative tool—the use of humanitarian aid—for the use and projection of American power in the early twentieth century. Drawing on their letters, diaries, recollections as well as their official reports on their work and the situation in Belgium, this dissertation argues that the early twentieth century formation of what we today understand to be non-state, international humanitarianism was partially established by Americans exercising explicit and implicit national power during the years of American neutrality in World War I. -

Draft-Encampment-Rules-Comments

From: Karyn Blasi To: Samaniego, Frances Cc: Chip Hellar Subject: Belltown: Encampments and Injection Site Date: Thursday, February 09, 2017 9:49:02 AM Importance: High Hello Frances, I was told you are reviewing public feedback regarding encampments and injection sites in Seattle. I am writing to you as a very concerned home owner in Belltown regarding the safety of my family (which includes a husband and two daughters ages 10 and 11). I am requesting that (1) the needle exchange/injection site be placed closer to Harborview or an appropriate hospital and not in Belltown and (2) that trespassers and encampments not be allowed anywhere in Belltown. My family and I have been exposed to incredibly disturbing drug addicted people who have been blocking the sidewalk under the Hwy99 northbound on ramp (photos attached and since I took those, it has gotten much worse, more than 8 tents). I have been contacting a variety of departments for clean up. And while they have responded, the trespassers come back the next day and set up camp again. This must stop. This sidewalk is a main thoroughfare to the Pike Place Market for us and many of our neighbors (and is in my backyard). Having trespassers blocking the sidewalk especially while using drugs is incredibly unsafe for us and our daughters. Thank you for your consideration and doing anything possible to ensure these encampments are removed permanently. Karyn Blasi Hellar From: Andrew Otterness To: Samaniego, Frances Subject: Camp on sidewalk Date: Friday, February 10, 2017 9:21:18 AM Frances: Albeit this very polite and informative reply from Shana at the city's Customer Service desk, my concern is that City of Seattle absolutely must not allow homeless camps on the sidewalks. -

Homelessness in the News 2013 Media Report

Homelessness in the News 2013 Media Report Education and Advocacy Department Prepared by: Katy Fleury, Education and Advocacy Coordinator [email protected] Homelessness in the News 2013 Media Report Table of Contents Overview ................................................................................................................................................................................ 2-3 Public Policy and Homelessness ................................................................................................................................... 4-9 Criminalization .......................................................................................................................................................... 4-6 Hate Crimes and Discrimination......................................................................................................................... 6-7 Federal Budget Cuts and Funding for Homeless Programs..................................................................... 7-8 Tent Cities and Camping Bans ............................................................................................................................. 8-9 Specific Populations ...................................................................................................................................................... 10-14 Families Experiencing Homelessness.......................................................................................................... 10-11 Unaccompanied Youth ...................................................................................................................................... -

There's a Skid Row Everywhere, and This Is Just

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2016 There’s a Skid Row Everywhere, and This is Just the Headquarters: Impacts of Urban Revitalization Policies in the Homeless Community of Skid Row Douglas Mungin Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Mungin, Douglas, "There’s a Skid Row Everywhere, and This is Just the Headquarters: Impacts of Urban Revitalization Policies in the Homeless Community of Skid Row" (2016). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 1693. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/1693 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. THERE’S A SKID ROW EVERYWHERE, AND THIS IS JUST THE HEADQUARTERS: IMPACTS OF URBAN REVITALIZATION POLICIES IN THE HOMELESS COMMUNITY OF SKID ROW A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Communication Studies by Douglas Mungin B.A., San Francisco State University, 2007 M.A., Louisiana State University, 2012 August 2016 Acknowledgements Thanks for taking this journey with me my ocean and little professor. This project would not be in existence if it were not for the tremendous support and guidance from my advisor Rachel Hall. -

Hoover Struggles with the Depression Sect. #3

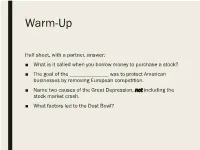

Warm-Up Half sheet, with a partner, answer: ■ What is it called when you borrow money to purchase a stock? ■ The goal of the ______________ was to protect American businesses by removing European competition. ■ Name two causes of the Great Depression, not including the stock market crash. ■ What factors led to the Dust Bowl? Warm-Up ■ What is it called when you borrow money to purchase a stock? – Buying on margin ■ The goal of the ______________ was to protect American businesses by removing European competition. – Hawley-Smoot Tariff ■ Name two causes of the Great Depression, not including the stock market crash. – War debts, tariffs, farm problems, easy credit, income disparity ■ What factors led to the Dust Bowl? – Drought, overworked soil, powerful winds HOOVER STRUGGLES WITH THE DEPRESSION Chapter 22.3 Hoover Tries to Reassure the Nation ■ Hoover’s Philosophy – Many experts believe depressions a normal part of business cycle – People should take care of own families; not depend on government ■ Hoover Takes Cautious Steps – Calls meeting of business, banking, labor leaders to solve problems ■ Creates organization to help private charities raise money for poor Hoover Reassures Nation Boulder Dam / Hoover Dam ■ Hoover’s Boulder Dam on Colorado River is massive project – later renamed Hoover Dam ■ Provides electricity, flood control, water to states on river basin Shift in Power ■ Democrats Win in 1930 Congressional Elections ■ As economic problems increase, Hoover, Republicans blamed ■ Widespread criticism of Hoover; shantytowns called “Hoovervilles” Hoover Takes Action ■ Federal Farm Board (organization of farm cooperatives) ■ buy crops, keep off market until prices rise ■ Direct Intervention – Federal Home Loan Bank Act lowers mortgage rates ■ Hoover’s measures do not improve economy before presidential election Gassing the Bonus Army ■ Bonus Army – veterans go to D.C. -

STAAR U.S. History Administered May 2017 Released

STAAR® State of Texas Assessments of Academic Readiness U.S. History Administered May 2017 RELEASED Copyright © 2017, Texas Education Agency. All rights reserved. Reproduction of all or portions of this work is prohibited without express written permission from the Texas Education Agency. U.S. HISTORY U.S. History Page 3 DIRECTIONS Read each question carefully. Determine the best answer to the question from thefouranswerchoicesprovided.Thenfill in theansweronyouranswer document. 1 The Progressive goal to implement women’s suffrage was accomplished by — A a national referendum B an executive order C a Supreme Court decision D a constitutional amendment U.S. History Page 4 2 This poster is from the first annual Earth Day in 1970. Source: Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division Earth Day was created for the purpose of — F celebrating the diversity of humankind G honoring the world’s agricultural workers H raising awareness of environmental issues J promoting peace throughout the world U.S. History Page 5 3 The Korean War was an effort by the United States to — A carry out its policy of containing the spread of communism B keep its economy strong by maintaining wartime activities C secure additional Asian trading partners D extend the principles of the Marshall Plan to Asia 4 A heat shield material designed to act as an insulating barrier is now used to protect high-rise buildings from fires. Source: NASA This technology was originally developed primarily to — F give rockets greater boost during takeoff G protect the space shuttle on reentry H provide astronauts with improved navigational equipment J slow down space capsules as they landed in the ocean 5 One reason the 2008 presidential election was historically significant is that it was the first time — A traditionally Republican states voted Democratic B voters used computerized ballots C an African American won the presidency D a Southerner won the vice-presidency U.S. -

Herbert Hoover Dealing with Disaster EPISODE

Herbert Hoover Dealing with disaster EPISODE TRANSCRIPT Listen to Presidential at http://wapo.st/presidential This transcript was run through an automated transcription service and then lightly edited for clarity. There may be typos or small discrepancies from the podcast audio. LILLIAN CUNNINGHAM: When I think of Herbert Hoover, this is what I think. SONG FROM 'ANNIE' LILLIAN CUNNINGHAM: It's a song from the musical, 'Annie.' The Great Depression is raging, and there's a scene where Little Orphan Annie stumbles into a Hooverville, which is what they called the shantytowns that sprung up when millions of Americans lost their jobs and their homes and were starving on the streets during the Depression. The word ‘Hooverville’ was, of course, a jab at President Hoover, who was in the White House as the country spiraled downward. So, this was basically the extent of my image of Hoover -- a failed president during the Great Depression. This week, we are going to get a much richer picture of him, starting with the fact that Hoover, like Annie, was an orphan. I'm Lillian Cunningham with The Washington Post, and this is the 30th episode of “Presidential.” PRESIDENTIAL THEME MUSIC LILLIAN CUNNINGHAM: Last week with Calvin Coolidge, we spent a lot of time talking about economics. So, this week, even though we're now at the Great Depression and there are a lot of interesting economic questions to explore, we're not actually going to get too into the weeds on economic policy. Instead, I'm interested in the fact that Hoover entered the White House looking extremely qualified for the role. -

Modern Charity: Morality, Politics, and Mid-Twentieth Century US Writing

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--English English 2019 Modern Charity: Morality, Politics, and Mid-Twentieth Century US Writing Matt Bryant Cheney University of Kentucky, [email protected] Author ORCID Identifier: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8237-6295 Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/etd.2020.027 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Bryant Cheney, Matt, "Modern Charity: Morality, Politics, and Mid-Twentieth Century US Writing" (2019). Theses and Dissertations--English. 101. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/english_etds/101 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the English at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--English by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

The World of Anne Frank: Through the Eyes of a Friend

1 Anne Frank and the Holocaust Introduction to the Guide This guide can help your students begin to understand Anne Frank and, through her eyes, the war Hitler and the Nazis waged against the Jews of Europe. Anne's viewpoint is invaluable for your students because she, too, was a teenager. Reading her diary will enhance the Living Voices presentation. But the diary alone does not explain the events that parallel her life during the Holocaust. It is these events that this guide summarizes. Using excerpts from Anne’s diary as points of departure, students can connect certain global events with their direct effects on one young girl, her family, and the citizens of Germany and Holland, the two countries in which she lived. Thus students come to see more clearly both Anne and the world that shaped her. What was the Holocaust? The Holocaust was the planned, systematic attempt by the Nazis and their active supporters to annihilate every Jewish man, woman, and child in the world. Largely unopposed by the free world, it resulted in the murder of six million Jews. Mass annihilation is not unique. The Nazis, however, stand alone in their utilization of state power and modern science and technology to destroy a people. While others were swept into the Third Reich’s net of death, the Nazis, with cold calculation, focused on destroying the Jews, not because they were a political or an economic threat, but simply because they were Jews. In nearly every country the Nazis occupied during the war, Jews were rounded up, isolated from the native population, brutally forced into detention camps, and ultimately deported to labor and death camps. -

The Great Depression

The American Yawp Chapter 23 – The Great Depression Quiz 1. What percent of Americans were investing in the stock market prior to the crash? a. 2.5% b. 10% c. 33% d. 66% 2. Which group of Americans benefitted the least from the economic changes of the 1920s? a. Unionized manufacturing laborers b. Southern farmers c. Northern bankers d. Female educators 3. What was the consequence of the Smoot-Hawley Tariff of 1930? a. Lowered prices on international goods b. Increased American exports c. Loosened banking regulation to increase financial liquidity d. International trade collapsed 4. How did the Federal Reserve respond to the financial collapse? a. Overcorrected by raising interest rates and tightening credit b. Flooded the market with low interest rates, increasing inflation c. The Federal Reserve did not take any consequential action d. Raised interest rates but increased subsidies for lenders 5. What is the definition of Herbert Hoover’s “Associationalism?” a. A belief that self-interest and greed are the surest routes to innovation and economic growth b. An adaption of European socialism designed to redistribute wealth c. A system where businesses would voluntarily limit harmful business practices for the greater economic good d. The use of Progressive Era regulation to protect workers and consumers 6. What was the Bonus Army? a. Bankers who were criticized in the press after receiving massive bonuses during the Great Depression b. The men under the command of General Douglas MacArthur who forcibly cleared the Hooverville that had formed in Washington D.C. c. Hoover’s team of financial advisers who designed the Reconstruction Finance Corporation d. -

New Jersey in the Great Depression by Arthur Guarino

Time of Despair, Time of Hope photo: David W. Steele 'Depression Breadline' by George Segal, 1999 - metal: bronze - Grounds for Sculpture, Hamilton, NJ http://www.groundsforsculpture.org/Artwork/Depression-Breadline New Jersey in the Great Depression by Arthur Guarino Time of Despair, Time of Hope Arthur Guarino | www.GardenStateLegacy.com Issue 24 June 2014 he Great Depression was an unprecedented period in our nation’s history in which the scars were deep and Tdevastating. The nation saw unemployment rates that never went below 14 percent and for a full four years—1932, 1933, 1934, and 1935—was never below 20 percent. In Detroit, Michigan, automobile production dropped by two-thirds, while the number of factory workers in the city’s biggest industry decreased by more than 50 percent. Many businesses across America were wiped out, never to open their doors again. Families lost their unprotected savings because they had trusted banks that were either poorly run or caught in the tide of the panics of the early 1930s. Children starved because their parents could not provide them food; young girls sold Top: The Trenton Evening Times from their bodies for a nickel just so they could eat. Men took to “Black Thursday.” www.genealogybank.com begging on the streets across America because they were out Above: A solemn crowd gathers of work and had no where to turn for help. Still other men outside the Stock Exchange after the abandoned their families and rode the rails across the United crash. States with the hope finding a job in a new city or state and be http://en.wikipedia.org Time of Despair, Time of Hope Arthur Guarino | www.GardenStateLegacy.com Issue 24 June 2014 able to regain their dignity.