Herbert Hoover Dealing with Disaster EPISODE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Motion Film File Title Listing

Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum (714) 983 9120 ◦ http://www.nixonlibrary.gov ◦ [email protected] MOTION FILM FILE ● MFF-001 "On Guard for America: Nixon for U.S. Senator TV Spot #1" (1950) One of a series of six: On Guard for America", TV Campaign spots. Features Richard M. Nixon speaking from his office" Participants: Richard M. Nixon Original Format: 16mm film Film. Original source type: MPPCA. Cross Reference: MVF 47 (two versions: 15 min and 30 min);. DVD reference copy available ● MFF-002 "On Guard For America: Nixon for U.S. Senator TV Spot #2" (1950) One of a series of six "On Guard for America", TV campaign spots. Features Richard Nixon speaking from his office Participants: Richard M. Nixon Original Format: 16mm film Film. Original source type: MPPCA. DVD reference copy available ● MFF-003 "On Guard For America: Nixon for U.S. Senator TV Spot #3" (1950) One of a series of six "On Guard for America", TV campaign spots. Features Richard Nixon speaking from his office. Participants: Richard M. Nixon Original Format: 16mm film Film. Original source type: MPPCA. DVD reference copy available Monday, August 06, 2018 Page 1 of 202 Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum (714) 983 9120 ◦ http://www.nixonlibrary.gov ◦ [email protected] MOTION FILM FILE ● MFF-004 "On Guard For America: Nixon for U.S. Senator TV Spot #4" (1950) One of a series of six "On Guard for America", TV campaign spots. Features Richard Nixon speaking from his office. Participants: Richard M. Nixon Original Format: 16mm film Film. Original source type: MPPCA. -

Hoovervilles: the Shantytowns of the Great Depression by History.Com, Adapted by Newsela Staff on 04.04.17 Word Count 702 Level 830L

Hoovervilles: The Shantytowns of the Great Depression By History.com, adapted by Newsela staff on 04.04.17 Word Count 702 Level 830L A typical shantytown of the Great Depression in the United States, this one located in a city. Photo: WPA The Great Depression was an economic crisis that began in 1929. Many people had invested money in the stock market and when it crashed they lost much of the money they had invested. People stopped spending money and investing. Banks did not have enough money, which led many people to lose their savings. Many Americans lost money, their homes and their jobs. Homeless Americans began to build their own camps on the edges of cities, where they lived in shacks and other crude shelters. These areas were known as shantytowns. As the Depression got worse, many Americans asked the U.S. government for help. When the government failed to provide relief, the people blamed President Herbert Hoover for their poverty. The shantytowns became known as Hoovervilles. In 1932, Hoover lost the presidential election to Franklin Roosevelt. Roosevelt created programs that helped lift the U.S. out of the Depression. By the early 1940s, most remaining Hoovervilles were torn down. This article is available at 5 reading levels at https://newsela.com. 1 The Great Depression sets in The Great Depression was one of the most terrible events of the 1900s, and led to a huge rise in unemployment. By 1933, 1 out of 4 Americans was out of work. Americans looked to the U.S. government for help. -

The President Also Had to Consider the Proper Role of an Ex * President

************************************~ * * * * 0 DB P H0 F E8 8 0 B, * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * The little-known * * story of how * a President of the * United States, Beniamin Harrison, helped launch Stanford law School. ************************************* * * * T H E PRESIDENT * * * * * * * * * * * * By Howard Bromberg, J.D. * * * TANFORD'S first professor of law was a former President of the United * States. This is a distinction that no other school can claim. On March 2, 1893, * L-41.,_, with two days remaining in his administration, President Benjamin Harrison * * accepted an appointment as Non-Resident Professor of Constitutional Law at * Stanford University. * Harrison's decision was a triumph for the fledgling western university and its * * founder, Leland Stanford, who had personally recruited the chief of state. It also * provided a tremendous boost to the nascent Law Department, which had suffered * months of frustration and disappointment. * David Starr Jordan, Stanford University's first president, had been planning a law * * program since the University opened in 1891. He would model it on the innovative * approach to legal education proposed by Woodrow Wilson, Jurisprudence Profes- * sor at Princeton. Law would be taught simultaneously with the social sciences; no * * one would be admitted to graduate legal studies who was not already a college * graduate; and the department would be thoroughly integrated with the life and * * ************************************** ************************************* * § during Harrison's four difficult years * El in the White House. ~ In 1891, Sena tor Stanford helped ~ arrange a presidential cross-country * train tour, during which Harrison * visited and was impressed by the university campus still under con * struction. When Harrison was * defeated by Grover Cleveland in the 1892 election, it occurred to Senator * Stanford to invite his friend-who * had been one of the nation's leading lawyers before entering the Senate * to join the as-yet empty Stanford law * faculty. -

American Identity, Humanitarian Experience, and the Commission for Relief in Belgium, 1914-1917 Thomas D

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 7-21-2014 Rough and Ready Relief: American Identity, Humanitarian Experience, and the Commission for Relief in Belgium, 1914-1917 Thomas D. Westerman University of Connecticut, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Westerman, Thomas D., "Rough and Ready Relief: American Identity, Humanitarian Experience, and the Commission for Relief in Belgium, 1914-1917" (2014). Doctoral Dissertations. 466. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/466 Rough and Ready Relief: American Identity, Humanitarian Experience, and the Commission for Relief in Belgium, 1914-1917 Thomas David Westerman, Ph.D. University of Connecticut, 2014 This dissertation examines a group of American men who adopted and adapted notions of American power for humanitarian ends in German-occupied Belgium with the Commission for Relief in Belgium (CRB) during World War I. The CRB, led by Herbert Hoover, controlled the importation of relief goods and provided supervision of the Belgian-led relief distribution. The young, college-educated American men who volunteered for this relief work between 1914 and 1917 constructed an effective and efficient humanitarian space for themselves by drawing not only on the power of their neutral American citizenship, but on their collectively understood American-ness as able, active, yet responsible young men serving abroad, thereby developing an alternative tool—the use of humanitarian aid—for the use and projection of American power in the early twentieth century. Drawing on their letters, diaries, recollections as well as their official reports on their work and the situation in Belgium, this dissertation argues that the early twentieth century formation of what we today understand to be non-state, international humanitarianism was partially established by Americans exercising explicit and implicit national power during the years of American neutrality in World War I. -

Draft-Encampment-Rules-Comments

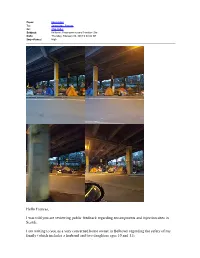

From: Karyn Blasi To: Samaniego, Frances Cc: Chip Hellar Subject: Belltown: Encampments and Injection Site Date: Thursday, February 09, 2017 9:49:02 AM Importance: High Hello Frances, I was told you are reviewing public feedback regarding encampments and injection sites in Seattle. I am writing to you as a very concerned home owner in Belltown regarding the safety of my family (which includes a husband and two daughters ages 10 and 11). I am requesting that (1) the needle exchange/injection site be placed closer to Harborview or an appropriate hospital and not in Belltown and (2) that trespassers and encampments not be allowed anywhere in Belltown. My family and I have been exposed to incredibly disturbing drug addicted people who have been blocking the sidewalk under the Hwy99 northbound on ramp (photos attached and since I took those, it has gotten much worse, more than 8 tents). I have been contacting a variety of departments for clean up. And while they have responded, the trespassers come back the next day and set up camp again. This must stop. This sidewalk is a main thoroughfare to the Pike Place Market for us and many of our neighbors (and is in my backyard). Having trespassers blocking the sidewalk especially while using drugs is incredibly unsafe for us and our daughters. Thank you for your consideration and doing anything possible to ensure these encampments are removed permanently. Karyn Blasi Hellar From: Andrew Otterness To: Samaniego, Frances Subject: Camp on sidewalk Date: Friday, February 10, 2017 9:21:18 AM Frances: Albeit this very polite and informative reply from Shana at the city's Customer Service desk, my concern is that City of Seattle absolutely must not allow homeless camps on the sidewalks. -

Post-Presidential Papers, 1961-69 1964 PRINCIPAL FILE Series

EISENHOWER, DWIGHT D.: Post-Presidential Papers, 1961-69 1964 PRINCIPAL FILE Series Description The 1964 Principal File, which was the main office file for Dwight D. Eisenhower’s Gettysburg Office, is divided into two subseries--a subject file and an alphabetical file. The subject subseries consists of a little over twenty-three boxes of material, and it is arranged alphabetically by subject. This subseries contains such categories as appointments, autographs, endorsements, gifts, invitations, memberships, memoranda, messages, political affairs, publications, statements, and trips. Invitations generated the greatest volume of correspondence, followed by appointments, messages, and gifts. Documentation in this subseries includes correspondence, schedules, agendas, articles, memoranda, transcripts of interviews, and reports. The alphabetical subseries, which has a little over thirty-four boxes, is arranged alphabetically by names of individuals and organizations. It is primarily a correspondence file, but it also contains printed materials, speeches, cross-reference sheets, interview transcripts, statements, clippings, and photographs. During 1964 Eisenhower was receiving correspondence from the public at the rate of over fifty thousand letters a year. This placed considerable strain on Eisenhower and his small office staff, and many requests for appointments, autographs, speeches, endorsements, and special messages met with a negative response. Although the great bulk of the correspondence in this series involves routine matters, there are considerable letters and memoranda which deal with national and international issues, events, and personalities. Some of the subjects discussed in Eisenhower’s correspondence include the 1964 presidential race, NATO, the U.S. space program, the U. S. economy, presidential inability and succession, defense policies, civil rights legislation, political extremists, and Cuba. -

Herbert Hoover Subject Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf758005bj Online items available Register of the Herbert Hoover subject collection Finding aid prepared by Elena S. Danielson and Charles G. Palm Hoover Institution Library and Archives © 1999 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305-6003 [email protected] URL: http://www.hoover.org/library-and-archives Register of the Herbert Hoover 62008 1 subject collection Title: Herbert Hoover subject collection Date (inclusive): 1895-2006 Collection Number: 62008 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Library and Archives Language of Material: English Physical Description: 354 manuscript boxes, 10 oversize boxes, 31 card file boxes, 2 oversize folders, 91 envelopes, 8 microfilm reels, 3 videotape cassettes, 36 phonotape reels, 35 phonorecords, memorabilia(203.2 Linear Feet) Abstract: Correspondence, writings, printed matter, photographs, motion picture film, and sound recordings, relating to the career of Herbert Hoover as president of the United States and as relief administrator during World Wars I and II. Sound use copies of sound recordings available. Digital copies of select records also available at https://digitalcollections.hoover.org. Access Boxes 382, 384, and 391 closed. The remainder of the collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. Publication Rights Published as: Hoover Institution on War, Revolution, and Peace. Herbert Hoover, a register of his papers in the Hoover Institution archives / compiled by Elena S. Danielson and Charles G. Palm. Stanford, Calif. : Hoover Institution Press, Stanford University, c1983 For copyright status, please contact Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Acquisition Information Acquired by the Hoover Institution Library & Archives in 1962. -

Addresses the American Road Herbert Hoover

ADDRESSES UPON THE AMERICAN ROAD BY HERBERT HOOVER 1955-1960 THE CAXTON PRINTERS, LTD. CALDWELL, IDAHO 1961 © 1961 BY HERBERT HOOVER NEW YORK. NEW YORK Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 61-5290 Printed and bound in the United States of America by The CAXTON PRINTERS, Ltd. Caldwell, Idaho 91507 Contents PART I: FOREIGN RELATIONS AN APPRAISAL OF THE CHANGES IN THE CHARTER OF THE UNITED NATIONS 3 [Statement of April 20, 1954] ON THE 15TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE BALTIC STATES FREEDOM COMMITTEE 11 [Letter to Dr. A, Trimakas, Chairman, Baltic States Freedom Committee, May 29, 1955] CONCERNING PRESIDENT EISENHOWER AND THE GENEVA CONFERENCE 12 [Statement to the Press, July 23, 1955] CHRISTMAS MESSAGE TO THE "CAPTIVE NATIONS" 13 [Letter to Mr. W. J. C. Egan, Director, Radio Free Europe, Broadcast at Christmas Time, November 30, 1955] ON THE 38TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE INDEPENDENCE OF ESTONIA 14 [Letter to The Estonian National Committee in the United States, February 15, 1956] MESSAGE TO THE PEOPLE OF HUNGARY 15 [Letter to Mr. Andrew Irshay, Hungarian Newspaperman in New Jersey, March 31, 1956] WORLD EXPERIENCE WITH THE KARL MARX WAY OF LIFE 16 [Address Before the Inter-American Bar Association, Dallas, Texas, April 16, 1956] ON RECREATION 27 [Message to the International Recreation Congress, New York City, September 21, 1956] ON THE OCCASION OF THE 5TH CONGRESS IN EXILE OF THE INTERNATIONAL PEASANT UNION 28 [Letter to Stanislaw Mikolajczyk, Paris, France, October 11, 1956] v CONCERNING HUNGARIAN PATRIOTISM 29 [Message Read at the Protest Meeting -

Franklin Roosevelt, Thomas Dewey and the Wartime Presidential Campaign of 1944

POLITICS AS USUAL: FRANKLIN ROOSEVELT, THOMAS DEWEY, AND THE WARTIME PRESIDENTIAL CAMPAIGN OF 1944 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. POLITICS AS USUAL: FRANKLIN ROOSEVELT, THOMAS DEWEY AND THE WARTIME PRESIDENTIAL CAMPAIGN OF 1944 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Michael A. Davis, B.A., M.A. University of Central Arkansas, 1993 University of Central Arkansas, 1994 December 2005 University of Arkansas Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the U.S. wartime presidential campaign of 1944. In 1944, the United States was at war with the Axis Powers of World War II, and Democrat Franklin D. Roosevelt, already serving an unprecedented third term as President of the United States, was seeking a fourth. Roosevelt was a very able politician and-combined with his successful performance as wartime commander-in-chief-- waged an effective, and ultimately successful, reelection campaign. Republicans, meanwhile, rallied behind New York Governor Thomas E. Dewey. Dewey emerged as leader of the GOP at a critical time. Since the coming of the Great Depression -for which Republicans were blamed-the party had suffered a series of political setbacks. Republicans were demoralized, and by the early 1940s, divided into two general national factions: Robert Taft conservatives and Wendell WiIlkie "liberals." Believing his party's chances of victory over the skilled and wily commander-in-chiefto be slim, Dewey nevertheless committed himself to wage a competent and centrist campaign, to hold the Republican Party together, and to transform it into a relevant alternative within the postwar New Deal political order. -

Herbert Hoover, Partisan Conflict, and the Symbolic Appeal Of

P1: Vendor International Journal of Politics, Culture and Society [ijps] ph152-ijps-452810 October 1, 2002 19:7 Style file version Nov. 19th, 1999 International Journal of Politics, Culture and Society, Vol. 16, No. 2, Winter 2002 (C 2002) Legacies Versus Politics: Herbert Hoover, Partisan Conflict, and the Symbolic Appeal of Associationalism in the 1920s Andrew J. Polsky,‡ and Olesya Tkacheva† The concept of a policy legacy has come into widespread use among schol- ars in history and the social sciences, yet the concept has not been subject to close scrutiny. We suggest that policy legacies tend to underexplain outcomes and minimize conventional politics and historical contingencies. These ten- dencies are evident in the revisionist literature on American politics in the aftermath of the First World War. That work stresses continuities between wartime mobilization and postwar policy, especially under the auspices of Herbert Hoover and the Commerce Department. We maintain that a rupture marks the transition between the war and the Republican era that followed and that the emphasis on wartime legacies distorts the political realities of the Harding–Coolidge era. We conclude by noting the risks of policy legacy approaches in historical analysis. KEY WORDS: policy legacy; Herbert Hoover; Republican party; partisanship; associa- tionalism. INTRODUCTION: LEGACIES THICK AND THIN Policy history scholars refer often to the idea of a policy legacy to help explain the durability or recurrence of policy patterns. The term “legacy” connotes something that has been handed down from one generation to another, an inheritance. Later generations of policy makers will look to the past as they try to grasp problems or seek lessons about success and failure; Hunter College and the Graduate School, CUNY. -

The Weekly Radio Addresses of Reagan and Clinton

Chapman University Chapman University Digital Commons Political Science Faculty Articles and Research Political Science 2006 New Strategies for an Old Medium: The eekW ly Radio Addresses of Reagan and Clinton Lori Cox Han Chapman University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/polisci_articles Part of the American Politics Commons, Communication Technology and New Media Commons, President/Executive Department Commons, and the Social Influence and Political Communication Commons Recommended Citation Han, Lori Cox. 2006. “New Strategies for an Old Medium: The eW ekly Radio Addresses of Reagan and Clinton.” Congress and the Presidency 33(1): 25-45. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Political Science at Chapman University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Political Science Faculty Articles and Research by an authorized administrator of Chapman University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. New Strategies for an Old Medium: The eekW ly Radio Addresses of Reagan and Clinton Comments This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published in Congress and the Presidency in 2006, available online at http://www.tandfonline.com/10.1080/07343460609507687. Copyright Taylor & Francis This article is available at Chapman University Digital Commons: http://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/polisci_articles/1 New Strategies for an Old Medium: The Weekly Radio Addresses of Reagan and Clinton “Of the untold values of the radio, one is the great intimacy it has brought among our people. Through its mysterious channels we come to wider acquaintance with surroundings and men.” President Herbert Hoover, Radio Address to the Nation, September 18, 1929 While president, Bill Clinton was never one to miss a public speaking opportunity. -

President Hoover: a Student Guide

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 388 559 SO 025 378 AUTHOR Evans, Mary TITLE President Hoover; A Student Guide. INSTITUTION Herbert Hoover Presidential Library-Museum, West Branch, IA. PUB DATE 94 NOTE 13p.; For related documents, see SO 025 379-381 and SO 025 383-384. AVAILABLE FROM Herbert Hoover Presidential Library, P.O. Box 488, West Branch, IA 52358. PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Use Teaching Guides (For Teacher) (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *American Studies; Federal Government; *Modern History; *Presidents of the United States; Sesondary Education; *Social History; Social Studies; State History; *United States History IDENTIFIERS *Hoover (Herbert) ABSTRACT This infoimation packet is intended for student use in research about the life of President Herbert Hoover. The packet is divided into three sections. Part 1 is "The Herbert Hoover Chronology," which sequences Hoover's accomplishments along with world events from his birth in 1874, until his death in 1964. Part 2 is "A Boyhood in Iowa," which is an excerpt taken from an informal address of boyhood recollections before the Iowa Society of Washington by Herbert Hoover in 1927 when he was 53 years old. Part 3 is "Presidential Cartoons," and shows artists' ways of portraying Hoover's accomplishments through illustrations. Lists of additional readings for students and teachers are included.(EH) * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. ********************************************************************** ?vesidentiN, I .E I'.113!,q1 . , c 4./6 EDLIC t . t. .0 ... (b. 4.1;"4^.' .49Q) :14 Lr'e FL11911W1 EV1 ..sseruilMiarida;=,,, !. West Branch, Iowa 3 "RERMISSIC.N 10 REPPO'.1l.,CE 1H6 MATERIAL HAS BEEN (,AAN'ED .)/V Herbert Hoover Chronology TO THE fl.