There's a Skid Row Everywhere, and This Is Just

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Excavating the Vine Street Expressway: a Tour of 1950'S Philadelphia Skid

Excavating the Vine Street Expressway: A Tour of 1950’s Philadelphia Skid Row Stephen Metraux [email protected] Article for hiddencityphila.org March 2017 An approach to Philadelphia not soon forgotten is on the beautiful [Benjamin Franklin] Bridge high over the river and the city, followed by Franklin Square – also known as “Bum’s Park.” When a traveler sees a tree-filled square with hundreds of men reclining on park benches or lined up for soup and salvation across the street then he has arrived in Philadelphia. The Health and Welfare Council (HWC) opened their 1952 report “What About Philadelphia’s Skid Row?” with this vignette of a motorist’s first impression of Philadelphia. Coming off the bridge from New Jersey, cars would land on Vine Street at 6th Street, with Franklin Square taking up the southern side of the block and the Sunday Breakfast Mission sitting on the northwest corner. This was the gateway to Skid Row, and, for the next three blocks, Vine Street was its main drag. What follows continues the Skid Row tour that the HWC report started 65 years ago by reconstructing this segment of 1950s Vine Street that now lies buried under its namesake expressway. The HWC report directed Philadelphia’s attention to its Skid Row. Generically, skid row denoted an area, present in larger mid-twentieth century American cities, that originated as a pre-Depression era district of itinerant and near indigent workingmen. As this population aged and dwindled after World War II, these areas retained signature amenities such as cheap hotels, religious missions, and bars, all ensconced by seediness and decay. -

Hoovervilles: the Shantytowns of the Great Depression by History.Com, Adapted by Newsela Staff on 04.04.17 Word Count 702 Level 830L

Hoovervilles: The Shantytowns of the Great Depression By History.com, adapted by Newsela staff on 04.04.17 Word Count 702 Level 830L A typical shantytown of the Great Depression in the United States, this one located in a city. Photo: WPA The Great Depression was an economic crisis that began in 1929. Many people had invested money in the stock market and when it crashed they lost much of the money they had invested. People stopped spending money and investing. Banks did not have enough money, which led many people to lose their savings. Many Americans lost money, their homes and their jobs. Homeless Americans began to build their own camps on the edges of cities, where they lived in shacks and other crude shelters. These areas were known as shantytowns. As the Depression got worse, many Americans asked the U.S. government for help. When the government failed to provide relief, the people blamed President Herbert Hoover for their poverty. The shantytowns became known as Hoovervilles. In 1932, Hoover lost the presidential election to Franklin Roosevelt. Roosevelt created programs that helped lift the U.S. out of the Depression. By the early 1940s, most remaining Hoovervilles were torn down. This article is available at 5 reading levels at https://newsela.com. 1 The Great Depression sets in The Great Depression was one of the most terrible events of the 1900s, and led to a huge rise in unemployment. By 1933, 1 out of 4 Americans was out of work. Americans looked to the U.S. government for help. -

[email protected] Sent

Archived: Monday, August 17, 2020 11:18:30 AM From: [email protected] Sent: Sunday, August 16, 2020 9:08:08 PM To: agenda comments; Mark Apolinar Subject: [EXTERNAL] Agenda Comments Response requested: Yes Sensitivity: Normal A new entry to a form/survey has been submitted. Form Name: Comment on Agenda Items Date & Time: 08/16/2020 9:08 pm Response #: 635 Submitter ID: 38307 IP address: 50.46.194.37 Time to complete: 6 min. , 20 sec. Survey Details: Answers Only Page 1 1. Margaret Willson 2. Shoreline 3. (○) Richmond Beach 4. [email protected] 5. 08/17/2020 6. 9(a) 7. Dear Shoreline City Council, I am writing about the low barrier Navigation Center being proposed for the former site of Arden Rehab on Aurora Avenue. I read the "Shoreline Area News" notes from your August 10 meeting, and I saw that many of you have embraced a "Housing First" approach to addressing homelessness. I've always been skeptical of the Housing First philosophy, because homelessness, rather than being a person's primarily problem, is usually a symptom of a deeper problem or problems. Fortuituously, I just this past week learned of a brand new report on Housing First by Seattle's own Christopher Rufo, who is a Visiting Fellow for Domestic Policy Studies at the Heritage Foundation. The report presents abundant evidence that Housing First works pretty well at keeping a roof over people's heads, but not so well at healing them and helping them turn their lives around. What does work to actually help people is "Treatment First". -

Michael Crichton and the Distancing of Scientific Discourse

ASp la revue du GERAS 55 | 2009 Varia Apparent truth and false reality: Michael Crichton and the distancing of scientific discourse Stéphanie Genty Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/asp/290 DOI: 10.4000/asp.290 ISBN: 978-2-8218-0408-1 ISSN: 2108-6354 Publisher Groupe d'étude et de recherche en anglais de spécialité Printed version Date of publication: 1 March 2009 Number of pages: 95-106 ISSN: 1246-8185 Electronic reference Stéphanie Genty, « Apparent truth and false reality: Michael Crichton and the distancing of scientific discourse », ASp [Online], 55 | 2009, Online since 01 March 2012, connection on 02 November 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/asp/290 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/asp.290 This text was automatically generated on 2 November 2020. Tous droits réservés Apparent truth and false reality: Michael Crichton and the distancing of scie... 1 Apparent truth and false reality: Michael Crichton and the distancing of scientific discourse Stéphanie Genty Introduction 1 This article began as an inquiry into the relation of FASP, or professional-based fiction, to professional reality. I was interested in elucidating the ways in which this reality, which formed the basis for such fiction, was transformed by the writer in his/her work and the reasons behind the transformation. Since my own professional activity has been related to the sciences, I chose to study the novels of Michael Crichton, a commercially-successful writer whose credentials and practice qualify him as an author of professional-based fiction as defined by Michel Petit in his 1999 article “La fiction à substrat professionnel: une autre voie d'accès à l'anglais de spécialité”. -

200 Protest War Taxes, Military International Workers Day AS

Volume 8, Number 14 U.C. San Diego 16th yearof publication April 19--May2, 1983 SanDiego Protests Target U.5. Military... 200 ProtestWar Taxes,Military A numberof eventsoccured last week the San Diego community,due to its in the San Diego community. From conser,,atismand the percentageof April10 through16 was National.lobs militaDand Federal retirees. In pointof withPeace Week. which had as its locus fact.the lailureof the rallyand its ho~ ourtax mone}is beingspent. It ~as organizersto definea politicalposition preceedcdon April9 by a rail,,,for Social on the issue also contributedto the Security. event’smoderate turnout. I n t heir’effort lhe April9Rally, held in BalboaPark to draw.the broadestpossible support IromI t~ 3 pm, was sponsoredby a wide for continuingSocial Security and rangeof senior,disabled, retired and protestagainst Reagan administr~,ti.n labor organizations,but drew’ only cuts.they watereddown the issueand about250 people. ’I he rallyfeatured a nearl}extinguished its militancy.Iotop key-notespeaker, a,, well as a numberoi it all off. local Mayoralcandidates 3-minute speeches fron| people Maureen ()’Connor and Roger representing various community Hedgecock made obligator} constituencies.A number of the speakers appearancesto garner ~otes. condemnedReagan, and one made the April15 haslong beena focus for anti- obvious connection between social war tax demonstrationsin ,";anI)iego servicecuts and increasesin military and around the nation, organized r ¯ principlyby the War ResistersLeague. Thousandswitness Tax Day Protestas motoristsdrive past picketers INSIDE THIS ISSUE: ~his year provedtO be no exception local War Resistersleague members, Draft Update along with membersof Red and Black Action.started earh. to organizeFax AS Elections:Politics AS Usual Lowery Speaks Out i)a~protests. -

The Bowery Series and the Transformation of Prostate Cancer, 1951–1966

This is a preprint of an accepted article scheduled to appear in the Bulletin of the History of Medicine. It has been copyedited but not paginated. Further edits are possible. Please check back for final article publication details. From Skid Row to Main Street: The Bowery Series and the Transformation of Prostate Cancer, 1951–1966 ROBERT ARONOWITZ SUMMARY: Between 1951 and 1966, more than 1,200 homeless, alcoholic men from New York’s skid row were subjected to invasive medical procedures, including open perineal biopsy of the prostate gland. If positive for cancer, men underwent prostatectomy, surgical castration, and estrogen treatments. The Bowery series was meant to answer important questions about prostate cancer’s diagnosis, natural history, prevention, and treatment. While the Bowery series had little ultimate impact on practice, in part due to ethical problems, its means and goals were prescient. In the ensuing decades, technological tinkering catalyzed the transformation of prostate cancer attitudes and interventions in directions that the Bowery series’ promoters had anticipated. These largely forgotten set of practices are a window into how we have come to believe that the screen and radical treatment paradigm in prostate cancer is efficacious and the underlying logic of the twentieth century American quest to control cancer and our fears of cancer. KEYWORDS: cancer, prostate cancer, history of medicine, efficacy, risk, screening, bioethics 1 This is a preprint of an accepted article scheduled to appear in the Bulletin of the History of Medicine. It has been copyedited but not paginated. Further edits are possible. Please check back for final article publication details. -

American Identity, Humanitarian Experience, and the Commission for Relief in Belgium, 1914-1917 Thomas D

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 7-21-2014 Rough and Ready Relief: American Identity, Humanitarian Experience, and the Commission for Relief in Belgium, 1914-1917 Thomas D. Westerman University of Connecticut, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Westerman, Thomas D., "Rough and Ready Relief: American Identity, Humanitarian Experience, and the Commission for Relief in Belgium, 1914-1917" (2014). Doctoral Dissertations. 466. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/466 Rough and Ready Relief: American Identity, Humanitarian Experience, and the Commission for Relief in Belgium, 1914-1917 Thomas David Westerman, Ph.D. University of Connecticut, 2014 This dissertation examines a group of American men who adopted and adapted notions of American power for humanitarian ends in German-occupied Belgium with the Commission for Relief in Belgium (CRB) during World War I. The CRB, led by Herbert Hoover, controlled the importation of relief goods and provided supervision of the Belgian-led relief distribution. The young, college-educated American men who volunteered for this relief work between 1914 and 1917 constructed an effective and efficient humanitarian space for themselves by drawing not only on the power of their neutral American citizenship, but on their collectively understood American-ness as able, active, yet responsible young men serving abroad, thereby developing an alternative tool—the use of humanitarian aid—for the use and projection of American power in the early twentieth century. Drawing on their letters, diaries, recollections as well as their official reports on their work and the situation in Belgium, this dissertation argues that the early twentieth century formation of what we today understand to be non-state, international humanitarianism was partially established by Americans exercising explicit and implicit national power during the years of American neutrality in World War I. -

Global Warming, the Politicization of Science, and Michael Crichton's State of Fear

Journal of Scientific Exploration, Vol. 19, No. 2, pp. 247-256, 2005 0892-33 1OlO5 Global Warming, the Politicization of Science, and Michael Crichton's State of Fear College of Geoscience University of Oklahoma Norman, Oklahoma 7301 9 e-mail: ddeming @ou.edu Abstract-Michael Crichton's book State of Fear addresses the politicization of science, in particular the topics of climate change and global warming, through the vehicle of a novel. In the author's opinion, Crichton is correct: the field of climate research has become highly politicized. An example is provided by the revisionist efforts of some researchers to extinguish the existence of a Medieval Warm Period. The politicization of science is a threat to the process of free inquiry necessary for human progress. Keywords: global warming-temperature-Crichton-climate- Medieval Warm Period On December 26, 2004, a magnitude 9.0 earthquake occurred off the coast of Northern Sumatra. The massive temblor, the largest in 40 years, spawned tsunamis that killed more than 280,000 people. The next day, a colleague at a think tank emailed me to ask whether I had any opinions about the new Michael Crichton book, State of Fear (Crichton, 2004). Although State of Fear is a fictional thriller about eco-terrorism, its real thesis is the politicization of science, in particular climate change and global warming. Because global warming is a highly-charged political subject, Crichton's book has received a lot of attention in the press, including a review by Washington Post columnist George Will (Will, 2004). My colleague closed his email with a little joke: P.S.-I'm also anxious to see if anyone blames this weekend's tsunami in Indonesia on global warming. -

Films on Homelessness and Related Issues A) VANCOUVER and BC FILMS SHORT FILMS Homelessnation.Org

Films on Homelessness and Related Issues A) VANCOUVER AND BC FILMS SHORT FILMS HomelessNation.Org: HN News and other shorts (Vancouver) The Vancouver branch of Homeless Nation, a national website for and by the homeless (www.homelessnation.org), produces regular short videos on issues related to homelessness. To see one of the HN News episodes: http://homelessnation.org/en/node/12956 For a list of all the posted videos: http://homelessnation.org/en/featuredvideos (includes one with Gregor Robertson in June 08 http://homelessnation.org/en/node/12552) List of Homeless Nation shorts provided by Janelle Kelly ([email protected]) http://www.homelessnation.org/en/node/5610 Powerful video in response to a friend's suicide http://www.homelessnation.org/en/node/5018 Not a youth video but a powerful piece on social housing in partnership with CCAP http://www.homelessnation.org/en/node/4789 Victoria and Vancouver video on homelessness from last year http://www.homelessnation.org/en/node/6902 Youth speak out about their views on harm reduction http://www.homelessnation.org/en/node/13110 Not on homelessness but amazing. Fraggle did this entire piece. http://www.homelessnation.org/node/12691 H/N news first episode http://www.homelessnation.org/en/node/6492 Not a youth video but really good characterization of life on the streets http://www.homelessnation.org/en/node/5896 Washing away the homeless 'yuppie falls'; what some business do to prevent homeless http://www.homelessnation.org/en/node/7211 Story of two youth that left Vancouver, -

2005-2006 Legislative Index

CALIFORNIA LEGISLATURE 2005–06 REGULAR SESSION 2005–06 FIRST EXTRAORDINARY SESSION 2005–06 SECOND EXTRAORDINARY SESSION PART 1 LEGISLATIVE INDEX and PART 2 TABLE OF SECTIONS AFFECTED FINAL EDITION November 30, 2006 GREGORY SCHMIDT E. DOTSON WILSON Secretary of the Senate Chief Clerk of the Assembly Compiled by DIANE F. BOYER-VINE Legislative Counsel LEGISLATIVE INDEX TO BILLS, CONSTITUTIONAL AMENDMENTS, JOINT AND CONCURRENT RESOLUTIONS, AND SINGLE-HOUSE RESOLUTIONS 2005–06 Regular Session 2005–06 First Extraordinary Session 2005–06 Second Extraordinary Session PREFACE This publication consists of an index to measures and a table of sections affected. It is cumulative and periodically published. INDEX The index indicates the subject of each bill, constitutional amendment, and resolution as introduced and as amended. Entries are not removed from the index when subject matter is deleted from the measure in course of passage. TABLE The table shows each section of the Constitution, codes, and uncodified laws affected by measures introduced in the Legislature. It may be used in two ways: 1. As a means of locating measures where the section of the Constitution, code, or law is known. 2. To locate measures upon a particular subject, by using a published index to the codes and laws, such as Deering’s General Index, the Larmac Consolidated Index, and West’s General Index, to locate the existing sections, and then by using this table to locate the measures which affect those sections. The table is arranged by codes and the Constitution listed in alphabeti- cal order. Uncodified laws are listed at the end of the table under the heading ‘‘Statutes Other Than Codes,’’ and are cited by year and chapter. -

Draft-Encampment-Rules-Comments

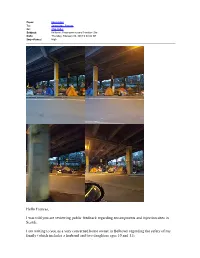

From: Karyn Blasi To: Samaniego, Frances Cc: Chip Hellar Subject: Belltown: Encampments and Injection Site Date: Thursday, February 09, 2017 9:49:02 AM Importance: High Hello Frances, I was told you are reviewing public feedback regarding encampments and injection sites in Seattle. I am writing to you as a very concerned home owner in Belltown regarding the safety of my family (which includes a husband and two daughters ages 10 and 11). I am requesting that (1) the needle exchange/injection site be placed closer to Harborview or an appropriate hospital and not in Belltown and (2) that trespassers and encampments not be allowed anywhere in Belltown. My family and I have been exposed to incredibly disturbing drug addicted people who have been blocking the sidewalk under the Hwy99 northbound on ramp (photos attached and since I took those, it has gotten much worse, more than 8 tents). I have been contacting a variety of departments for clean up. And while they have responded, the trespassers come back the next day and set up camp again. This must stop. This sidewalk is a main thoroughfare to the Pike Place Market for us and many of our neighbors (and is in my backyard). Having trespassers blocking the sidewalk especially while using drugs is incredibly unsafe for us and our daughters. Thank you for your consideration and doing anything possible to ensure these encampments are removed permanently. Karyn Blasi Hellar From: Andrew Otterness To: Samaniego, Frances Subject: Camp on sidewalk Date: Friday, February 10, 2017 9:21:18 AM Frances: Albeit this very polite and informative reply from Shana at the city's Customer Service desk, my concern is that City of Seattle absolutely must not allow homeless camps on the sidewalks. -

2008 TRASH Regionals Round 10 Tossups 1. This Person Is Deemed

2008 TRASH Regionals Round 10 Tossups 1. This person is deemed superior to both Francesca in the Guggenheim and a social psychology professor in Baskin- Robbins. She likes her Scotch aged eighteen years. Her name is Janine, although she doesn't want to be called that. She has been encountered in a car by the side of the road, in a tub, and on a pool table, with the latter fulfilling her paramour's prom night pact. John, played by John Cho, popularized the term "MILF" in describing, for ten points, what older woman played by Jennifer Coolidge, the lover of Finch in the American Pie movies? Answer: Stifler's Mom or Mrs. Stifler (accept Janine Stifler on early buzz) 2. His 1984 graphical text adventure, Amazon, sold 100,000 copies. A personal friend of Jasper Johns, he published an appreciation of his work, as well as a book on BASIC programming, Electronic Life. Hollywood work included the script for Extreme Close Up as well as directing Looker and Physical Evidence. His pen names included Michael Lange, a pun on the German word for "tall", and Jeffrey Hudson, the name of a 17th century dwarf, under which he wrote A Case of Need. For ten points, name this author of The Terminal Man, Congo, and State of Fear, who recently died of cancer at the age of 66. Answer: Michael Crichton 3. This show's second episode, "Birdcage," featured a cameo by Audrina Partridge from The Hills. The third, "Dosing," sees the staff's bonus checks held hostage to a feud between the general manager, Neal, and HR director Rhonda, which is defused when the owner's wife tries to seduce Neal.