Honorifics in Japanese Sentence Interpretation: Clues to the Missing Actor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Honorificity, Indexicality and Their Interaction in Magahi

SPEAKER AND ADDRESSEE IN NATURAL LANGUAGE: HONORIFICITY, INDEXICALITY AND THEIR INTERACTION IN MAGAHI BY DEEPAK ALOK A dissertation submitted to the School of Graduate Studies Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Linguistics Written under the direction of Mark Baker and Veneeta Dayal and approved by New Brunswick, New Jersey October, 2020 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Speaker and Addressee in Natural Language: Honorificity, Indexicality and their Interaction in Magahi By Deepak Alok Dissertation Director: Mark Baker and Veneeta Dayal Natural language uses first and second person pronouns to refer to the speaker and addressee. This dissertation takes as its starting point the view that speaker and addressee are also implicated in sentences that do not have such pronouns (Speas and Tenny 2003). It investigates two linguistic phenomena: honorification and indexical shift, and the interactions between them, andshow that these discourse participants have an important role to play. The investigation is based on Magahi, an Eastern Indo-Aryan language spoken mainly in the state of Bihar (India), where these phenomena manifest themselves in ways not previously attested in the literature. The phenomena are analyzed based on the native speaker judgements of the author along with judgements of one more native speaker, and sometimes with others as the occasion has presented itself. Magahi shows a rich honorification system (the encoding of “social status” in grammar) along several interrelated dimensions. Not only 2nd person pronouns but 3rd person pronouns also morphologically mark the honorificity of the referent with respect to the speaker. -

What Happened to the Honorifics in a Local Japanese Dialect in 55 Years: a Report from the Okazaki Survey on Honorifics

University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics Volume 18 Issue 2 Selected Papers from NWAV 40 Article 7 9-2012 What Happened to the Honorifics in a Local Japanese Dialect in 55 years: A Report from the Okazaki Survey on Honorifics Kenjiro Matsuda Kobe Shoin Women’s University Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/pwpl Recommended Citation Matsuda, Kenjiro (2012) "What Happened to the Honorifics in a Local Japanese Dialect in 55 years: A Report from the Okazaki Survey on Honorifics," University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics: Vol. 18 : Iss. 2 , Article 7. Available at: https://repository.upenn.edu/pwpl/vol18/iss2/7 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/pwpl/vol18/iss2/7 For more information, please contact [email protected]. What Happened to the Honorifics in a Local Japanese Dialect in 55 ears:y A Report from the Okazaki Survey on Honorifics Abstract This paper reports the analysis of the three trend samples from the Okazaki Honorifics Survey, a longitudinal survey by the National Language Research Institute on the use and the awareness of honorifics in Okazaki city, Aichi Prefecture in Japan. Its main results are: (1) the Okazakians are using more polite forms over the 55 years; (2) the effect of the three social variables (sex, age, and educational background), which used to be strong factors controlling the use of the honorifics in the speech community, are diminishing over the years; (3) in OSH I and II, the questions show clustering by the feature [±service interaction], while the same 11 questions in OSH III exhibit clustering by a different feature, [±spontaneous]; (4) the change in (3) and (4) can be accounted for nicely by the Democratization Hypothesis proposed by Inoue (1999) for the variation and change of honorifics in other Japanese dialects. -

Korean Honorific Speech Style Shift: Intra-Speaker

KOREAN HONORIFIC SPEECH STYLE SHIFT: INTRA-SPEAKER VARIABLES AND CONTEXT A DISSERATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN EAST ASIAN LANGUAGES AND LITERATURES (KOREAN) MAY 2014 By Sumi Chang Dissertation Committee: Ho-min Sohn, Chairperson Dong Jae Lee Mee Jeong Park Lourdes Ortega Richard Schmidt Keywords: Korean honorifics, grammaticalization, indexicality, stance, identity ⓒ Copyright 2014 by Sumi Chang ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS No words can express my appreciation to all the people who have helped me over the course of my doctoral work which has been a humbling and enlightening experience. First, I want to express my deepest gratitude to my Chair, Professor Ho-min Sohn, for his intellectual guidance, enthusiasm, and constant encouragement. I feel very fortunate to have been under his tutelage and supervision. I also wish to thank his wife, Mrs. Sook-Hi Sohn samonim, whose kindness and generosity extended to all the graduate students, making each of us feel special and at home over the years. Among my committee members, I am particularly indebted to Professor Dong Jae Lee for continuing to serve on my committee even after his retirement. His thoughtfulness and sense of humor alleviated the concerns and the pressure I was under. Professor Mee Jeong Park always welcomed my questions and helped me organize my jumbled thoughts. Her support and reassurance, especially in times of self-doubt, have been true blessings. Professor Lourdes Ortega's invaluable comments since my MA days provided me with a clear direction and goal. -

Logical Structure and Case Marking in Japanese

1 Logical Structure and Case Marking in Japanese by Shingo Imai A project submitted to the Department of Linguistics State University of New York at Buffalo in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts March, 1998 2 Table of Contents Abstract i Abbreviations ii Notes on Transcriptions ii Acknowledgments iii Introduction 1 Chapter 1: Theoretical Background 1.1. Logical structures and macroroles 3 1.2. Case 6 1.3. Nexus and Juncture 7 Chapter 2: Logical Structure and Case 2.0. Introduction 11 2.1. Transitive construction 11 2.2. Ditransitive construction 14 2.3. Invesion constrution (Nominative-dative construction) 23 2.4. Nominative-ni postposition construction 2.4.1. Motion verbs 31 2.4.2. Verbs of arriving 33 2.5. Possessor-raising (double nominative) construction 34 2.6. Causative construction 38 2.7. Passive construction 2.7.0. Introduction 40 2.7.1. Direct passive (revised) 44 2.7.2. Indirect passive 44 2.7.3. Possessor-raising passive 49 Chapter 3: Syntactic Characteristics 3.0. Introduction 54 3.1. Controllers of the ‘subject’-honorific predicate 54 3.2. Reflexive zibun 61 3.3. Controllers of the -nagara ‘while’ clause 67 Conclusion 73 References 76 i Logical Structures and Case Marking Systems in Japanese Shingo Imai Abstract Logical structures and case marking systems in Japanese are investigated in the framework of Role and Reference Grammar. Chapter one summarizes theoretical backgrounds. In chapter two, transitive, ditransitive, inversion, possessor-raising, causative, direct passive, and indirect passive constructions are discussed. In chapter three, syntactic behaviors such as so-called ‘subject’-honorific predicates, a reflexive zibun, and gaps of nagara- ‘while’ clauses are investigated. -

Yuliya Walsh Dissertation [email protected]

FORMS OF ADDRESS IN CONTEMPORARY UKRAINIAN NEWSPAPERS: Morphology, Gender and Pragmatics DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Yuliya Walsh Graduate Program in Slavic and East European Languages and Cultures The Ohio State University 2014 Dissertation Committee: Daniel Collins, Advisor, Predrag Matejic, Brian Joseph Copyright by Yuliya Walsh 2014 Abstract This dissertation examines variation in nominal (unbound) address forms and related constructions in contemporary (post-Soviet) Ukrainian. The data come from 134 randomly selected articles in two Ukrainian newspapers dating from 1998–2013. Among the morphological and syntactic issues that receive particular attention are the allomorphy of the Ukrainian vocative and the spread of vocative markings to new categories (e.g., last names). In addition, the dissertation examines how the vocative behaves in apposition with other noun phrases; this sheds light on the controversial question of the status of the vocative in the Ukrainian case system. Another syntactic issue discussed in the study is the collocability of the unbound address and deferential reference term pan, which has become widespread in the post-Soviet period. The dissertation also examines several pragmatic issues relevant for the variation in contemporary Ukrainian address. First, it investigates how familiarity and distance affect the choice of different unbound address forms. Second, it examines how the gender of the speech act participants (addresser and addressee) influence preferencs for particular forms of address. Up to now, there have been scarcely any investigations of Ukrainian from the viewpoint of either pragmatics or gender linguistics. -

Agreement in Slavic*

http://seelrc.org/glossos/ The Slavic and East European Language Resource Center [email protected] Greville G. Corbett University of Surrey Agreement in Slavic* 1. Introduction Agreement in Slavic has attracted and challenged researchers for many years. Besides numerous theses and articles in journals and collections on the topic, there are also several monographs, usually devoted to a single language, sometimes broader in scope.1 One aim is to give a synthesis of this research, demonstrating both the complexity of the topic and the interest of some of the results (section 2). Such a synthesis is complicated by the liveliness of current work, which is both deepening our understanding of the scale of the problems and trying to bring formal models closer to being able to give adequate accounts of well-established phenomena. A further aim, then, is to outline this current work (section 3). Finally the paper suggests a prospective of promising and challenging directions for future research, some which arise naturally from the directions of earlier and current work, some which are less obvious, depending on cross-disciplinary collaboration (section 4). As preparation for the main sections, we first consider the terms we require and the advantages which the Slavic family provides for research on agreement. * The support of the ESRC (grants R000236063 and R000222419) and of the ERC (grant ERC-2008-AdG-230268 MORPHOLOGY) is gratefully acknowledged. I also wish to thank Dunstan Brown, Iván Igartua and the participants at the workshop “Comparative Slavic Morphosyntax”, especially Wayles Browne, for comments on an earlier version. This overview was prepared for publication after the Workshop and has been updated since; I thank Claire Turner for help in the preparation of the revised version. -

Cross-Cultural Pragmatics: Honorifics in British English, Peninsular

DEPARTAMENT DE FILOLOGIA ANGLESA I DE GERMANÍSTICA Cross-Cultural Pragmatics: Honorifics in British English, Peninsular Spanish and Ukrainian Treball de Fi de Grau/ BA dissertation Author: Kateryna Koval Supervisor: Sònia Prats Carreras Grau d’Estudis Anglesos/Grau d’Estudis d’Anglès i Francès June 2019 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would first like to thank my tutor, Sònia Prats Carreras, who helped me to choose the topic for my dissertation as well as to develop it. Additionally, I would like to acknowledge Yolanda Rodríguez and Natalya Dychka, who both provided me with valuable advices concerning the use of honorifics in Spanish and Ukrainian, respectively. TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ........................................................................................................................ 1 1. Introduction .............................................................................................................. 2 2. Cross-cultural and Politeness pragmatics ................................................................... 4 2.1. The cultural approach to pragmatics................................................................... 4 2.2. Characteristics of politeness ............................................................................... 5 3. Pronouns of address and honorific titles .................................................................... 8 4. Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions Theory .................................................................. 11 5. Comparison ............................................................................................................ -

Title: the Grammar of Slavic Honorifics Author: Gilbert C

Title: The Grammar of Slavic Honorifics Author: Gilbert C. Rappaport, University of Texas at Austin Agreement is the morphosyntactic process by which an inherent property of one syntactic element (the controller) affects the grammatical form of another element (the target). The well-documented phenomenon of mixed agreement results when a single controller gives contradictory results in two targets. An example is the well-known Russian наш врач Вера Ивановна пришла ‘ourMasc doctor Vera Ivanovna arrivedFem’, or in British English the committeeSg havePl decided. Mixed agreement almost invariably entails one of the controller values being semantically transparent (the feminine and plural predicates above, respectively). In Slavic, mixed agreement can involve gender, number, or person. The author has been developing a theory of mixed agreement in Slavic based on the distinction between a lexical Noun Phrase (NP), where lexically-determined grammatical features reside, and a functional Determiner Phrase (DP) containing the NP, where referential features reside. Consistent with the Agreement Hierarchy (Corbett 1979), in cases of mixed agreement the form of the predicate is more semantically transparent than is the form of an attributive, because the predicate ‘sees’ the DP, but not the NP inside the DP. The present paper looks at Slavic honorific constructions in which a conflict between form and content can be observed, possibly giving mixed agreement, but not necessarily. In Russian Доктор, что Вы советуетe? ‘Doctor, what do you advisePl’, the plural verb form stands in conflict with the singular reference of the pronoun. Mixed agreement is seen in Где Ваше благородие были? ‘Where wasPl yourSg honor?’ Such examples indicate that the honorific plural (pluralis maestaticus) applies at the DP level, not the NP level. -

Japanese Verbal Morphology in Coordination

Workshop on Suspended Affixation Cornell University October 26-27, 2012 Japanese Verbal Morphology in Coordination Kunio Nishiyama / Ibaraki University ([email protected]) This paper lays out data and issues that arise when verbs are coordinated in Japanese. Typically with the structure [V1 and V2] T, only V2 gets the tense marker. Thus, affixation for V1 is “suspended”. Other verbal affixes also show suspension, but the nature of recoverability is different for each affix. Suspended affixation is simply unrecoverable (tense), recoverable with an allomorph (negation), recoverable with a different interpretation (causative), and recoverable without a twist (aspectual auxiliary). Suspended affixation is analyzed as post-syntactic merger, and when it is not allowed, that is due to the defective nature of each conjunct (like clitics), not because of the pre-syntactic nature of the derivation. Some comparisons with English are also made. 1. Basic facts about suspended affixation in Japanese verbal domain 2. Various nature of the recoverability of the suspended affix 3. Previous works (syntax vs. lexicon) 4. Apparent TP coordination 5. Comparison with English: A unified approach 6. Two factors that rule out SA 7. Nominal domain 1. Suspended affixation in verbal coordination (1) a. John-wa yoku manabi1 yoku asob-u J.-Top well study well play-Pres ‘John [studies a lot] and [plays a lot].’ b. Taro-ga utai odot-ta T.-Nom sing dance-Past ‘Taro [sang] and [danced].’ Although the first conjunct does not have a tense marker, it has the same interpretation of tense as the second conjunct. (1a-b) can be analyzed as coordination of VP or V. -

Mirativity in Korean and Bulgarian

Third International Academic Conference of KACEES 1 Bulgaria, Korea, Central & East Europe - Humanities and Social Science 14th – 15th July, 2003Sofia University, Sofia, Bulgaria Mirativity in Korean and Bulgarian So Yong Kim, Krasimira Aleksova І. Introduction The present paper studies from a typological point of view the grammatical means for encoding a speaker’s surprise at an unexpected real fact in Korean and Bulgarian. In the first section we examine the semantics of the phenomenon and present briefly a few approaches to it. The nest part is an attempt at a typological classification of languages on the grounds of the grammatical status of mirative forms employed by the respective language(s). The main aim is to discover and demonstrate the places of Bulgarian and Korean in such a typological classification and specify the similarities and differences in the grammatical means for expressing the speaker’s astonishment. The third part focuses on the morphological patterns and types of marking specific for Bulgarian and Korean. It contains an overview of the grammatical system of the languages and some particular mirative uses. II. The semantics of mirativ forms The mirative is used to express the assessment of the knowledge background of the speaker – a fact little known to the speaker turns out to be truthful and the conclusion about the mismatch between the foreseen, expected, supposed and the real fact encites the astonishment of the speaker. The surprise expressed by the mirative forms is caused by the discrepancy between what is expected and what thing really are (see Guéncheva 1990) and as such encodes the transition of the speaker from a state of non-knowledge into a state of knowledge (see Nitsolova 1993). -

3 Honorifics: the Cultural Specificity of a Universal Mechanism in Japanese

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by SOAS Research Online 3 Honorifics: The cultural specificity of a universal mechanism in Japanese Barbara Pizziconi 3.1 Introduction Honorifi cs have been the object of linguistic enquiry for much longer than the broader notion of ‘politeness’ itself,1 but in spite of such long-standing investi- gations they pose an epistemological challenge. As grammaticalised linguistic devices typically interpreted as markers of deference to people of higher sta- tus, they are commonly conceived as exhibiting a ‘core’ deferential meaning, coded in the very honorifi c form, therefore constant across instances of use and always presupposed. Deferential forms are assumed to selectively mark literal or metaphorical distinctions of rank or horizontal distance, and therefore we are left to explain how meanings other than social ranks and roles – e.g. affective stances such as aggression or hypocrisy, intimacy, affection – can be routinely conveyed by the same forms. For example, in studies of business dis- course, use of honorifi cs can be taken to modulate power differentials, through the signalling of deference to such power, or the exercise of power itself; in studies on gendered discourse, they can be taken to index, via manipulation of the core meaning of deference, positions of subordination or authority. Issues of power are, of course, of central importance for performing gender or pro- fessional identities, but assuming the expression of a deferential intent in any occurrence of an honorifi c form carries the risk of over-attribution or blatant misinterpretation. Japanese studies of honorifi cs have identifi ed a number of regular uses of honorifi c forms that have traditionally been categorised as ‘secondary’ mean- ings. -

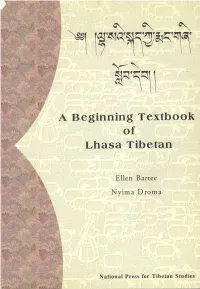

Tibetan, a Beginning Textbook of Lhasa

A Beginning Textbook of Lhasa Tibetan C\ C\ C\ -y^ A Beginning Textbook of Lhasa Tibetan Ellen Bartee Nyima Droma National Press for Tibetan Studies 2000 Cataloging in Publication Data Bartee, Ellen Nyima Droma A Beginning Textbook of Lhasa Tibetan Edited by Nganwan Pincuo, designed by Li Jianxiong Includes glossary 1. Language, Tibetan, Elementary 2. Linguistics, Tibeto-Burman ISBN 7-80057-430-X/G.19 First printed in 1999 by the Summer Institute of Linguistics. Revised version reprinted in 2000 by National Press for Tibetan studies. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, photoprint, microfilm, or any other means, except for personal use. CONTENTS Preface... vii Lesson One The Tibetan alphabet 9 Lesson Two Prefixes and suffixes 13 Lesson Three Superscribed and subjoined letters 17 Lesson Four What is this? 23 Lesson Five What nationality are you? 31 Lesson Six Where are you from? 37 Lesson Seven Tell me about yourself and your family 45 Lesson Eight Where are you going? What do you do? 55 honorifics and ^5] Q5) Lesson Nine What time is it? 67 NO Lesson Ten Eating and drinking 79 Lesson Eleven Everyday activities 89 Lesson Twelve Making plans and setting a date 95 review of verbs and ^1/^ Lesson Thirteen Going to Lhasa 105 |C |^ l*|q| ^ Lesson Fourteen What are you doing? 115 Tl <W §c ^c *H and the ergative marker ^ Lesson Fifteen Arriving in Lhasa 129 v Lesson Sixteen Tibetan tea 139 3*1 R^ ^ Lesson Seventeen Visiting a doctor 147 ~S \3 NO Lesson Eighteen At the store , 155 adjective forms (^ ^^ 5 $), comparative marker ^^ and the question particle ^^ Appendix I: Answers for practice work .