KOTRI BARRAGE REHABILITATION PROJECT (Loan 1101-PAK[SF])

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Presentation on Water Sector Development

PRESENTATION ON WATER SECTOR DEVELOPMENT By AFTAB AHMAD KHAN SHERPAO Minister for Water and Power At Pakistan Development Forum March 18, 2004 COUNTRY PROFILE • POPULATION: 141 MILLION • GEOGRAPHICAL AREA: 796,100 KM2 • IRRIGATED AREA: 36 MILLION ACRES • ANNUAL WATER AVAILABILITY AT RIM STATIONS: 142 MAF • ANNUAL CANAL WITHDRAWALS: 104 MAF • GROUND WATER PUMPAGE: 44 MAF • PER CAPITA WATER AVAILABLE (2004): 1200 CUBIC METER CURRENT WATER AVAILABILITY IN PAKISTAN AVAILABILITY (Average) o From Western Rivers at RIM Stations 142 MAF o Uses above Rim Stations 5 MAF TOTAL 147 MAF USES o Above RIM Stations 5 MAF o Canal Diversion 104 MAF TOTAL 109 MAF BALANCE AVAILABLE 38 MAF Annual Discharge (MAF) 100 20 40 60 80 0 76-77 69.08 77-78 30.39 (HYDROLOGICAL YEAR FROMAPRILTOMARCH) (HYDROLOGICAL YEAR FROMAPRILTOMARCH) 78-79 80.59 79-80 29.81 ESCAPAGES BELOW KOTRI 80-81 20.10 81-82 82-83 9.68 33.79 83-84 45.91 84-85 29.55 85-86 10.98 86-87 26.90 87-88 17.53 88-89 52.86 Years 89-90 17.22 90-91 42.34 91-92 53.29 92-93 81.49 93-94 29.11 94-95 91.83 95-96 62.76 96-97 45.40 97-98 20.79 98-99 AVG.(35.20) 99-00 8.83 35.15 00-01 0.77 01-02 1.93 02-03 2.32 03-04 20 WATER REQUIREMENT AND AVAILABILITY Requirement / Availability Year 2004 2025 (MAF) (MAF) Surface Water Requirements 115 135 Average Surface Water 104 104 Diversions Shortfall 11 31 (10 %) (23%) LOSS OF STORAGE CAPACITY Live Storage Capacity (MAF) Reservoirs Original Year 2004 Year 2010 Tarbela 9.70 7.28 25% 6.40 34% Chashma 0.70 0.40 43% 0.32 55% Mangla 5.30 4.24 20% 3.92 26% Total 15.70 11.91 10.64 -

PESA-DP-Hyderabad-Sindh.Pdf

Rani Bagh, Hyderabad “Disaster risk reduction has been a part of USAID’s work for decades. ……..we strive to do so in ways that better assess the threat of hazards, reduce losses, and ultimately protect and save more people during the next disaster.” Kasey Channell, Acting Director of the Disaster Response and Mitigation Division of USAID’s Office of U.S. Foreign Disas ter Ass istance (OFDA) PAKISTAN EMERGENCY SITUATIONAL ANALYSIS District Hyderabad August 2014 “Disasters can be seen as often as predictable events, requiring forward planning which is integrated in to broader de velopment programs.” Helen Clark, UNDP Administrator, Bureau of Crisis Preven on and Recovery. Annual Report 2011 Disclaimer iMMAP Pakistan is pleased to publish this district profile. The purpose of this profile is to promote public awareness, welfare, and safety while providing community and other related stakeholders, access to vital information for enhancing their disaster mitigation and response efforts. While iMMAP team has tried its best to provide proper source of information and ensure consistency in analyses within the given time limits; iMMAP shall not be held responsible for any inaccuracies that may be encountered. In any situation where the Official Public Records differs from the information provided in this district profile, the Official Public Records should take as precedence. iMMAP disclaims any responsibility and makes no representations or warranties as to the quality, accuracy, content, or completeness of any information contained in this report. Final assessment of accuracy and reliability of information is the responsibility of the user. iMMAP shall not be liable for damages of any nature whatsoever resulting from the use or misuse of information contained in this report. -

Water Resources Development in Pakistan a Revisit of Past Studies

World Water Day 22nd March, 2014 56 WATER RESOURCES DEVELOPMENT IN PAKISTAN A REVISIT OF PAST STUDIES By Engr. Abdul Khaliq Khan1 Abstract Three-fourths of the Earth’s surface is covered with water. Only 1% of the World’s water is usable, about 97% is salty sea water and 2% is frozen in glaciers and ice caps. All life on earth depends on water. Population is increasing and hence water availability per person is reducing. Civilizations have historically flourished around rivers and major waterways and for centuries these waterways have been a source of their livelihood. In modern times a remarkable irrigation network was developed by the British in the Indus river basin and at the time of partition the dividing line of the sub-continent disregarded not only the topography but also the irrigation boundaries of the then existing canal supply system. This created great challenges for the water resources development work in Pakistan. This paper discusses the importance of water and its role in the economic development of a country through increase in agricultural and industrial development. It traces the path as to how in Pakistan over the last 67 years various studies were carried out for the planning and development of water resources in the country. It discusses the steps that need to be taken today so that ample water is made available for our future generations for their survival. 1. INTRODUCTION All life on Earth depends on water, whether it is a plant in a desert, an animal in a wilderness, an insect in a rock crevice or a fish in a lake. -

Pakistan Public Expenditure Management, Volume II

Report No. 25665-PK PAKISTAN Public Expenditure Management Accelerated Development of Water Resources and Irrigated Agriculture VOLUME II January 28, 2004 Environment and Social Development Sector Unit Rural Development Sector Unit South Asia Region Document of the World Bank CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS Currency Unit = Pakistan Rupee US $1 = PKR 57.8 FISCAL YEAR July 1-June 30 ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ADB Asian Development Bank MIS Management information system ADP Annual Development Plan MOWP Ministry of Water and Power AWB Area Water Board MTEF Medium Term Expenditure Framework BCM Billion cubic meters MTIP Medium Term Investment Plan CCA Canal command area NDP National Drainage Program DMP Drainage Master Plan NDS National Drainage System EFR Environmental Flow Requirement NSDS National System Drainage Study EIRR Economic internal rate of return NWFP North West Frontier Province FATA Federally Administered Tribal Areas NWP National Water Policy FGW Fresh groundwater OFWM On-farm water management FO Farmer organization O&M Operations and Maintenance GDP Gross development product PIDA Provincial Irrigation and Drainage Authority GIS Geographic Information System POE Panel of Experts GOP Government of Pakistan PRHS Pakistan Rural Household Survey HYV High yielding variety PSDP Public Sector Development Program IBIS Indus basin irrigation system PV Present Value IDA International Development Association RAP Revised Action Plan IPPs Independent Power Producers RBOD Right Bank Outfall Drain IRSA Indus River System Authority SCARP Salinity control -

The Geographic, Geological and Oceanographic Setting of the Indus River

16 The Geographic, Geological and Oceanographic Setting of the Indus River Asif Inam1, Peter D. Clift2, Liviu Giosan3, Ali Rashid Tabrez1, Muhammad Tahir4, Muhammad Moazam Rabbani1 and Muhammad Danish1 1National Institute of Oceanography, ST. 47 Clifton Block 1, Karachi, Pakistan 2School of Geosciences, University of Aberdeen, Aberdeen AB24 3UE, UK 3Geology and Geophysics, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Woods Hole, MA 02543, USA 4Fugro Geodetic Limited, 28-B, KDA Scheme #1, Karachi 75350, Pakistan 16.1 INTRODUCTION glaciers (Tarar, 1982). The Indus, Jhelum and Chenab Rivers are the major sources of water for the Indus Basin The 3000 km long Indus is one of the world’s larger rivers Irrigation System (IBIS). that has exerted a long lasting fascination on scholars Seasonal and annual river fl ows both are highly variable since Alexander the Great’s expedition in the region in (Ahmad, 1993; Asianics, 2000). Annual peak fl ow occurs 325 BC. The discovery of an early advanced civilization between June and late September, during the southwest in the Indus Valley (Meadows and Meadows, 1999 and monsoon. The high fl ows of the summer monsoon are references therein) further increased this interest in the augmented by snowmelt in the north that also conveys a history of the river. Its source lies in Tibet, close to sacred large volume of sediment from the mountains. Mount Kailas and part of its upper course runs through The 970 000 km2 drainage basin of the Indus ranks the India, but its channel and drainage basin are mostly in twelfth largest in the world. Its 30 000 km2 delta ranks Pakiistan. -

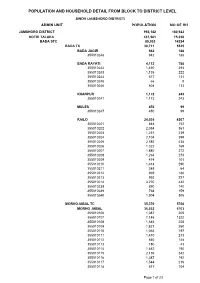

Jamshoro Blockwise

POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL SINDH (JAMSHORO DISTRICT) ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH JAMSHORO DISTRICT 993,142 180,922 KOTRI TALUKA 437,561 75,038 BADA STC 85,033 14234 BADA TC 30,711 5525 BADA JAGIR 942 188 355010248 942 188 BADA RAYATI 4,112 788 355010242 1,430 294 355010243 1,135 222 355010244 677 131 355010245 66 8 355010246 804 133 KHANPUR 1,173 243 355010241 1,173 243 MULES 450 99 355010247 450 99 RAILO 24,034 4207 355010201 844 152 355010202 2,054 361 355010203 1,251 239 355010204 2,104 399 355010205 2,585 438 355010206 1,022 169 355010207 1,880 272 355010208 1,264 273 355010209 474 101 355010210 1,414 290 355010211 348 64 355010212 969 186 355010213 993 227 355010214 3,270 432 355010238 890 140 355010239 768 159 355010240 1,904 305 MORHOJABAL TC 35,370 5768 MORHO JABAL 35,032 5703 355010106 1,087 205 355010107 7,146 1322 355010108 1,646 228 355010109 1,821 260 355010110 1,065 197 355010111 1,410 213 355010112 840 148 355010113 180 43 355010114 1,462 190 355010115 2,136 342 355010116 1,387 192 355010117 1,544 216 355010118 617 104 Page 1 of 23 POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL SINDH (JAMSHORO DISTRICT) ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH 355010119 79 15 355010120 3,665 538 355010121 951 129 355010122 2,161 343 355010123 2,169 355 355010124 1,468 261 355010125 2,198 402 TARBAND 338 65 355010126 338 65 PETARO TC 18,952 2941 ANDHEJI-KASI 1,541 292 355010306 1,541 292 BELO GHUGH 665 134 355010311 665 134 MANJHO JAGIR 659 123 355010307 659 123 MANJHO RAYATI 1,619 306 355010310 1,619 -

Gilgit-Baltistan: an Overview

SCHOLAR WARRIOR Gilgit-Baltistan: An Overview SENGE SERING Gilgit-Baltistan is a part of the state of Jammu and Kashmir but remains in the illegal occupation of Pakistan. It has an area of 76, 000 square kilometers, almost equal to the area of Assam. Around two million people call it their home. These include Tajiks, Dardic, Burushu and Tibetans. Farming, tourism and gem trading are the main sources of income. Economic Development In the context of macro-level development, the Government of Pakistan has adopted a top down approach with government organisations and corporations determining and leading the development projects, leaving little or no role for the local population in the decision making process. The benefits in the larger context often come in the long term but seldom accrue to the people at whose expense sacrifices have been made. For micro-level development, there is a bottom up approach mostly led by NGOs like Aga Khan Foundation. Decision making is at the grassroots level, aimed at capacity building to sustain livelihoods at the local level. Chinese Interests China’s interests mainly pertain to large scale strategic and economic projects. Locals have no role in planning, policy formulation, execution and benefit distribution. The sectors that the Chinese engage in are building trade and transit routes and tunnels, construction of dams, the energy sector, and mining of 64 ä SPRING 2012 ä SCHOLAR WARRIOR SCHOLAR WARRIOR Its location in a uranium, gold, copper and other metals and minerals. highly seismic zone Chinese are now aggressively acquiring mining sites here. Chinese future plans in the region relate to is a source of great construction of rail tracks, gas and oil pipelines. -

10-35 Waterworldwaterday 22 March 2014Water and Anex Izharul

World Water Day 22nd March, 2014 10 WATER ENERGY NEXUS By Dr. Izhar ul Haq1 SYNOPSIS Pakistan has on the average about 145 MAF of surface flows per annum. Out of this on average 103 MAF is diverted for irrigation at various barrages, 10 MAF is the system loss and 32 MAF goes down the last barrage into sea every year. Mangla and Tarbela two mega Dams were built as a part of the replacement works of the Indus Basin Plan. Their storage capacity has reduced due to sedimentation. There are about 100 small to medium dams on tributaries but their storage capacity is small. Pakistan has presently storage capacity of 10% of annual flows against 40% World average. Construction of Kalabagh Dam is stalled due to non consensus of the provinces. Diamer Basha Dam, having the approval of Council of Common Interest and Political Consensus, is ready for construction since 2008 and is still awaiting the financing arrangement for construction. These are only a couple of mega storage sites on main river Indus. Pakistan must build storage dams not only for food self sufficiency but also for cheap hydropower and flood mitigation. Pakistan has hydropower potential of 60,000 MW out of which it has exploited only 11%. The share of hydropower has reduced from 60% to 32% of the total power generated. The dependence on the imported fossil fuel (oil) has pushed the power tariff upwards. Pakistan has 18 small to medium hydel stations and only 3 stations greater than 1000 MW. The hydel power produced by Mangla and Tarbela has been the main stay in the economy of Pakistan. -

Transboundary River Basin Overview – Indus

0 [Type here] Irrigation in Africa in figures - AQUASTAT Survey - 2016 Transboundary River Basin Overview – Indus Version 2011 Recommended citation: FAO. 2011. AQUASTAT Transboundary River Basins – Indus River Basin. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Rome, Italy The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of FAO. FAO encourages the use, reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product. Except where otherwise indicated, material may be copied, downloaded and printed for private study, research and teaching purposes, or for use in non-commercial products or services, provided that appropriate acknowledgement of FAO as the source and copyright holder is given and that FAO’s endorsement of users’ views, products or services is not implied in any way. All requests for translation and adaptation rights, and for resale and other commercial use rights should be made via www.fao.org/contact-us/licencerequest or addressed to [email protected]. -

Life Science Journal 2013;10(3) Http

Life Science Journal 2013;10(3) http://www.lifesciencesite.com Pakistan’s Hydro Potential and Energy Crisis Tahir Mahmood 1, Hasham Khan 2, Mohammad Ahmad Choudhry 1 1. Department of Electrical Engineering, University of Engineering & Technology, Taxila 47050, Pakistan 2. Department of Electrical Engineering, GCT, Abbottabad, Pakistan [email protected] Abstract: Pakistan has abundant water resources. Hydro-potential resources can play effective role in contributing towards energy security as well as energy independence of Pakistan. This research paper delineates hydro potential in Pakistan. At present, Pakistan is facing severe short fall of electric energy. A brief history and the present situation of the hydro-electricity production, its consumption in the country and importance of utilization of water resources for the production of electric power have been discussed. Predictions to solve energy crises are made on the basis of empirical data and preliminary observations. The root causes of the shortfall in energy generation, an estimated forecast of demand and generation of electricity for the next twenty years has also been predicted. Energy projections have been discussed in detail. [T. MAhmoo, H. Khan, M.A. Choudhry. Pakistan’s Hydro Potential and Energy Crisis. Life Sci J 2013;10(3):1059-1069] (ISSN:1097-8135). http://www.lifesciencesite.com. 154 Keywords: Energy crisis, electricity generation, hydro potential. 1. Introduction facing by the whole world now a day. At present, the Pakistan, at present facing serious short fall duration of forced load shedding in peak season is of electric energy and this has evolved as crises. All between 8 hrs to 10 hrs in urban areas while 16 hrs to kinds of industries as well as common man had been 18 hours in rural areas. -

Worldwide Attacks Against Dams

Worldwide Attacks Against Dams A Historical Threat Resource for Owners and Operators 2012 i ii Preface This product is a compilation of information related to incidents that occurred at dams or related infrastructure world-wide. The information was gathered using domestic and foreign open-source resources as well as other relevant analytical products and databases. This document presents a summary of real-world events associated with physical attacks on dams, hydroelectric generation facilities and other related infrastructure between 2001 and 2011. By providing an historical perspective and describing previous attacks, this product provides the reader with a deeper and broader understanding of potential adversarial actions against dams and related infrastructure, thus enhancing the ability of Dams Sector-Specific Agency (SSA) partners to identify, prepare, and protect against potential threats. The U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) National Protection and Programs Directorate’s Office of Infrastructure Protection (NPPD/IP),which serves as the Dams Sector- Specific Agency (SSA), acknowledges the following members of the Dams Sector Threat Analysis Task Group who reviewed and provided input for this document: Jeff Millenor – Bonneville Power Authority John Albert – Dominion Power Eric Martinson – Lower Colorado River Authority Richard Deriso – Federal Bureau of Investigation Larry Hamilton – Federal Bureau of Investigation Marc Plante – Federal Bureau of Investigation Michael Strong – Federal Bureau of Investigation Keith Winter – Federal Bureau of Investigation Linne Willis – Federal Bureau of Investigation Frank Calcagno – Federal Energy Regulatory Commission Robert Parker – Tennessee Valley Authority Michael Bowen – U.S. Department of Homeland Security, NPPD/IP Cassie Gaeto – U.S. Department of Homeland Security, Office of Intelligence and Analysis Mark Calkins – U.S. -

Irrigation System, Arid Piedmont Plains of Southern Khyber-Paktunkhwa (NWFP), Pakistan; Issues & Solutions

Irrigation System, Arid Piedmont Plains of Southern Khyber-Paktunkhwa (NWFP), Pakistan; Issues & Solutions Muhammad Nasim Golra Javairia Naseem Golra Department of Irrigation, AGES Consultants, Government of Khyber-Paktunkhwa, Peshawar Peshawar IRRIGATION POTENTIAL Khyber-Paktunkhwa (Million (NWFP) Acres) Total Area (NWFP+FATA) 25.4 Cultivable Area 6.72 Irrigated Area Govt. Canals 1.2467 Civil Canals 0.82 Lift Irrigation Schemes 0.1095 Tube Wells/Dug Wells 0.1008 Total 2.277 Potential Area for Irrigation 4.443 Lakki Marwat 0.588 D.I. Khan 1.472 Tank 0.436 Total 2.496 Rest of Province 1.947 Upper Siran Canal Kunhar River Siran River Lower Siran Canal Icher Canal Haro River Irrigation System , KP (NWFP) Indus River Daur River Khan Pur Dam Sarai Saleh Channel L.B.C R.B.C Mingora 130 miles 40 miles 96 miles Swat River Tarbela Dam P.H.L.C Ghazi Brotha Barrage Topi Bazi Irrigation Scheme Pehur Main Swabi Swan River Amandara H/W Indus River Chashma Barrage Machai Branch U.S.C Taunsa Barrage Lower Swat Kalabagh Barrage Kabul River Mardan Nowshera D.I.Khan Kohat Toi CRBC Kohat Munda H/W Panj Kora River Peshawar Main Canal L.B. Canal CRBC 1st Lift 64 Feet Tanda Dam K.R.C CRBC 2nd Lift 120 Feet Warsak Canal Bannu CRBC 3rd Lift 170 Feet Warsak Lift Canal Tank Civil Canal Kurram Ghari H/W Kurram Tangi Dam Marwat Canal Baran Dam Gomal River Kurram River Tochi Baran Link D.I. Khan-Tank Gomal Zam Dam Area Kaitu River Tochi River Flood Irrigation Vs Canal Irrigation Command D.