Chapter 3. Highlighted Projects and Their Progress by Country

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Skripsi Yunda

CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 General Overview of Research Object 1.1.1 Light Rail Transit Figure 1.1 LRT Source : www.kabar3.com The Palembang Light Rail Transit (Palembang LRT) is an operational light rail transit system in Palembang, Indonesia which connects Sultan Mahmud Badaruddin II International Airport and Jakabaring Sports City. Starting construction in 2015, the project was built to facilitate the 2018 Asian Games and was completed in mid-2018, just a few months before the event. Costing Rp 10.9 trillion for construction, the system is the first operational light rail transit system in Indonesia, and utilizes trains made by local manufacturer PT.INKA. The system's only line has a total of 13 stations (6 operational). As Palembang was to host the 2018 Asian Games, the project was pushed to be completed before the event began. Groundbreaking for the project occurred on 1 November 2015, with state-owned company Waskita Karya being appointed as the primary contractor following the issuance of Presidential Regulation 116 of 2015 on Acceleration of Railway Train Operation in South Sumatera Province. The contract, which was signed in February 2017, was initially valued at Rp 12.5 trillion. Construction was scheduled for completion in February 2018, with commercial service beginning in May 2018. However, the completion date was moved to June 2018 with operations beginning in July, only one month before the Asian Games. A test run was done on 22 May 2018 and was inaugurated by President Joko Widodo on 15 July 2018. Operations for the LRT started on 1 August, several days before the Jakarta LRT began running, making it the first operational LRT system in the country. -

CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background Tourism Is One Of

CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background Tourism is one of sectors that supports a developing country, especially in social and economic activities. Its incomes are taken from the devise that come from tourism sectors such as tourism destination that give contribution from charge of visitors act. It also able to decrease the number of unemployment by recruiting the volunteer employees. For example, SEA GAMES 2011 and Islamic Solidarity Games 2013 in Palembang. This event required a lot of Palembang’s society to run that activities. There was an activity to develop tourism industry in a country, such as organizing big events. This program had effect directly of tourism activities in a country, its country will be more well-known than before because visitors will come to a country from these events. These actitivies will be increase the government and society’s incomes of a country. Tourism is the process of travelling to go to another place and temporary to enjoy the tourist attraction. Tourism is divided into several types such as cultural tourism, pleasure tourism, recreation tourism, business tourism, convention tourism, and sport tourism. One type of tourism that gets a lot of attention nowadays is the sport tourism. Sport tourism is a kind of journey to participate in sports activities, whether for recreation, competition, as well as travelling to sites such as sports stadiums (Gibson, Attle & Yiannakis, 1997). Indonesia is one of developing countries especially in tourism sector. Tourism destinations in Indonesia have been developed in many cities such as Jakarta, Yogyakarta, Bali, and Palembang. There are tourist destination in Jakarta such as Monumen Nasional (MONAS), Taman Mini Indonesia Indah (TMII), Ancol Dreamland, and so on. -

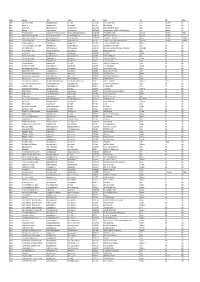

Trams Der Welt / Trams of the World 2021 Daten / Data © 2021 Peter Sohns Seite / Page 1

www.blickpunktstrab.net – Trams der Welt / Trams of the World 2021 Daten / Data © 2021 Peter Sohns Seite / Page 1 Algeria ... Alger (Algier) ... Metro ... 1435 mm Algeria ... Alger (Algier) ... Tram (Electric) ... 1435 mm Algeria ... Constantine ... Tram (Electric) ... 1435 mm Algeria ... Oran ... Tram (Electric) ... 1435 mm Algeria ... Ouragla ... Tram (Electric) ... 1435 mm Algeria ... Sétif ... Tram (Electric) ... 1435 mm Algeria ... Sidi Bel Abbès ... Tram (Electric) ... 1435 mm Argentina ... Buenos Aires, DF ... Metro ... 1435 mm Argentina ... Buenos Aires, DF - Caballito ... Heritage-Tram (Electric) ... 1435 mm Argentina ... Buenos Aires, DF - Lacroze (General Urquiza) ... Interurban (Electric) ... 1435 mm Argentina ... Buenos Aires, DF - Premetro E ... Tram (Electric) ... 1435 mm Argentina ... Buenos Aires, DF - Tren de la Costa ... Tram (Electric) ... 1435 mm Argentina ... Córdoba, Córdoba ... Trolleybus Argentina ... Mar del Plata, BA ... Heritage-Tram (Electric) ... 900 mm Argentina ... Mendoza, Mendoza ... Tram (Electric) ... 1435 mm Argentina ... Mendoza, Mendoza ... Trolleybus Argentina ... Rosario, Santa Fé ... Heritage-Tram (Electric) ... 1435 mm Argentina ... Rosario, Santa Fé ... Trolleybus Argentina ... Valle Hermoso, Córdoba ... Tram-Museum (Electric) ... 600 mm Armenia ... Yerevan ... Metro ... 1524 mm Armenia ... Yerevan ... Trolleybus Australia ... Adelaide, SA - Glenelg ... Tram (Electric) ... 1435 mm Australia ... Ballarat, VIC ... Heritage-Tram (Electric) ... 1435 mm Australia ... Bendigo, VIC ... Heritage-Tram -

ECC News, April - June 2017 1 I Hope to Live up to the Confidence That You Have Put in Place with Me

ECC News, April - June 2017 1 I HOPE TO LIVE UP TO THE CONFIDENCE THAT YOU HAVE PUT IN PLACE WITH ME amazing qualities of making use of It’s fortunate today for me that out of forward in digital, smart world, defence, special company. It has been a leader in and unimaginable. All I can say is thank every working minute to make every day others you have chosen me to step into etc. It’s a very special company and you technologies. It has done unique projects you very much for having reposed your meaningful towards the organisation’s the new role as CEO & MD of L&T. It is have correctly coined the statement that & makes unique products. trust and faith on me. I have absolutely no growth is a superb way towards creating not only inheriting the great set of assets, “We make things that make India doubt that your active mentorship across We been in existence for over 79 years. value. many of which have been created by you, proud”. the last decade and more has resulted in Since the time we have gone public, but a great brand and a terrific feeling me being what I am today and many of You have taken Larsen & Toubro from a The value systems that have been we have paid dividends every year. Each that I will be working with a fantastic set your facets, habits and positivity, to the good engineering company to one of the continuously stressed and laid great year’s dividend amount being higher of colleagues, peers and stakeholders. -

Creating Youthquake 4.0 Through Social Media for Optimizing the Use of Mass Rapid Transportation in Urban Areas

http://ejournal.stipjakarta.ac.id/index.php/pcsa Creating Youthquake 4.0 Through Social Media for Optimizing The Use of Mass Rapid Transportation in Urban Areas Melkisedek N. A. Kamagie1, Miftahul Rahma2, Syarifah Salsabi3, Purnama N.F. Lumban Batu4 1, 2, 3 Prodi Ketatalaksanaan Angkutan Laut dan Kepelabuhanan 1, 2, 3 Sekolah Tinggi Ilmu Pelayaran, Jakarta Jl. Marunda Makmur No. 1 Cilincing, Jakarta Utara. Jakarta 14150 Abstract This paper aimed to find out way millennials could optimize the use of Mass Rapid Transportation in urban areas through social media. It was focused on a social change that could be generated by millennials. Thus, it adopted qualitative method by using survey results from other researchers work related to Mass Rapid Transportation, millennials and social media use. The survey results were analyzed to see the relationship between millennials and social media for optimizing the use Mass Rapid Transportation by urban society. The result showed that the use of Mass Rapid Transportation could be optimized by creating Youthquake 4.0. It is a social change resulted from millennials’ action in changing people perception through social media. This could be done through the most use social media platforms, such as Facebook and Instagram. They have features, such as, captions, pictures, and hashtags that are proven could influence people’s perceptions. Copyright © 2019, Prosiding Seminar Hasil Penelitian Dosen Key words: youthquake 4.0, millennials, social media, Mass Rapid Transportation Permalink/ DOI : https://doi.org/10.36101/pcsa.v1i1.87 1. INTRODUCTION This problem can be improved by changing the Transportation development is a vital condition. -

THE ROLE of HISTORICAL SCIENCES on the DEVELOPMENT of URBAN PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION in 21St CENTURY INDONESIA

THE ROLE OF HISTORICAL SCIENCES ON THE DEVELOPMENT OF URBAN PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION IN 21st CENTURY INDONESIA 1 Muhammad Luthfi Lazuardi, 2 Moses Glorino Rumambo Pandin 1 2 Faculty of Humanities, Airlangga University [email protected]; [email protected] ABSTRACT Public transportation is one of the most critical needs for a city, including in Indonesia. The fast and dynamic movement of society makes public transportation expected to accommodate the needs of city residents to move more quickly and efficiently. Available public transport can also reduce congestion because many city residents are switching from their private vehicles. Many cities in Indonesia are competing to develop their public transportation to modernize the life of the town. Problems will arise if the city government does not learn from history in planning the development of public transport in the city. This study aims to examine the role of historical science in the development of urban public transportation in Indonesia. The method used in this research is descriptive-qualitative through literature review by analyzing data and information according to the topic of the research topic. The data and information are sourced from 20 journal articles and five credible online portal sites with published years between 2019-2021. The result of this study is the role of historical science in the development of urban public transportation in Indonesia as a reference for city governments to reorganize their transportation systems in the future. This research has research limitations on the development of urban public transport in Indonesia in the 21st century. -

Developing Local Stories of Palembang to Be an Authentic English Reading Texts

English Empower, Vol.03 No.02 61 DEVELOPING LOCAL STORIES OF PALEMBANG TO BE AN AUTHENTIC ENGLISH READING TEXTS Nurul Fitriyah Almunawaroh English Lecturer of Faculty of Teacher Training and Education Study Program, Tamansiswa University of Palembang [email protected] Kuntum Trilestari* English Lecturer of Faculty of Teacher Training and Education Study Program, Tamansiswa University of Palembang [email protected] Abstract: Many local stories of Palembang are published in the internet and some of them are translated by using google translate which are having lots of errors in grammatical form and the words choice are not suitable. Not only in term of grammar, some of the texts are not valid based on the history part. Unfortunately, when we search some of the history places, culture of even special food of Palembang at the official website of Department of Culture and Tourism Palembang, there only few stories uploaded. The aims of the study are ; 1) to find out the total number of Published local stories of Palembang; 2) to find out the authenticity or originality of local stories of Palembang available on the internet and other media; and 3) to find out the validity of local stories of Palembang available on the Internet or in other media in term of diction, grammar, readability, availability, and accuracy? The findings of the study hopefully can be used as the authentic English reading texts for public and school needs. There are sixteen texts translated in English and the readability also found to give the information of reading level of the texts. Keywords: Local stories of Palembang, English reading authentics text, readability INTRODUCTION of this capital city fits with its tophography Palembang is one of seventeen regencies which is surrounded or even covered by in South Sumatra Province. -

2018 Jakarta Palembang Asian Games – Event Advisory

RISK RATING MODERATE EVENT ADVISORY 18th Asian Games – Jakarta Palembang 2018 18th Asian Games, Jakarta and Palembang 2018: Event Advisory 18 AUGUST to 02 SEPTEMBER 2018 INDONESIA RISK SUMMARY: RISK LEVELS OVERALL MODERATE Insurance: Ensure your travel insurance covers ALL POLITICAL MODERATE activities. Travel & Accommodation: ARMED CONFLICT MODERATE Book in advance. Passport: Ensure your TERRORISM MODERATE passport is valid for more than 6 months and you have CRIME MODERATE a visa if required. Book Ahead: Planning your CIVIL UNREST MODERATE journey is important. MARITIME & PIRACY HIGH Vaccinations: Check your vaccinations are appropriate. HEALTH MODERATE Language: Learning some simple Indonesian terms will ENVIRONMENTAL MODERATE assist. OPERATING ENVIRONMENT KEY FACTS COUNTRIES ATHLETES TICKETS SECURITY EVENTS Estimated 9.6 million (Jakarta, 2016 estimated) Population: Geographic Area: 6,392 km2 (Jakarta metro) Language: Indonesian (Bahasa) and more than 700 other languages 45 11,000 1.3MILLION 100,000 462 At the time of writing, An estimated 11,000 1.3 million tickets are set Organisers have There are 462 events to Religion: Six recognised religions – Islam, Protestantism, 45 National Olympic athletes are to be made available to confirmed that be held in the games in 40 sports and 63 Catholicism, Hinduism, Buddhism, and Committees have expected to spectators, with more 100,000 security disciplines, in everything Confucianism confirmed attendance participate in the available if early sales personnel will be from aquatics to wushu, at the Asian Games. Games. By some are strong. The average deployed in Jakarta, and fencing to rugby. Climate: Tropical Competing associations estimates, they are ticket price is set to be Palembang and West This marks the first Asian include ‘Independent the largest multi- $7, with prices as low as Java, where several Games with events held UTC: +7 (Jakarta) Asian Athletes’. -

Copy of 20191114 DEAKIN COLLEGE AGENT LIST.Xlsx

Country Agent name Email Website Phone Address City State Postcode Albania Bridge Blue Pty Ltd ‐ Albania [email protected] Not Provided 377 45 255 988 K2‐No.6 Rruga Naim Frashëri Tiranë Not Provided 1001 Albania Study Care ‐ Tirana [email protected] www.studycate.al Not Provided Abdyl Frasheri Street Tirana Not Provided 1000 Algeria MasterWise Algeria algiers@master‐wise.com www.master‐wise.com 213 021 27 4999 116 Boulevard Des Martyrs el Madania Algiers Not Provided 16075 Argentina ACE Australia info@ace‐australia.com www.ace‐australia.com 54 911 38195291 Av Sargento Cayetano Beliera 3025 Edificio M3 2P Parque Austral Pilar Buenos Aires 1629 Argentina CW International Education [email protected] http://www.cwinternationaleducation.com 54 11 4801 0867 J.F. Segui 3967 Piso 6 A (1425) Buenos Aires Not Provided C1057AAG Argentina Latino Australia Education ‐ Buenos Aires [email protected] http://www.latinoAustralia.com 54 11 4811 8633 Riobamba 972 4‐C / Capital Federal Buenos Aires Not Provided 1618 Argentina Latino Australia Education ‐ Mendoza [email protected] www.latinoAustralia.com 54 261 439 0478 R. Obligado 37 ‐ Oficina S3 Godoy Cruz Mendoza Not Provided Not Provided Argentina TEDUCAustralia ‐ Buenos Aires [email protected] www.teducAustralia.com Not Provided 25 de Mayo 252 2‐B Vicente Lopez Provincia de Buenos Aires Buenos Aires Not Provided Not Provided Australia 1st Education Australia Pty Ltd [email protected] www.1stedu.com.au 08 7225 8699 Unit 4, Level 12, -

LRT (Light Rail Transit / Lintas Rel Terpadu) Adalah Salah Satu

CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background “LRT (Light Rail Transit / Lintas Rel Terpadu) adalah salah satu transportasi umum jenisnya kereta yang merupakan bagian prasarana dan sarana dalam sistem transportasi umum,” (Setijowarno, 2019). It means LRT is one of the public transportations that is similar with train and it is the part of infrastructure and facilities in the public transportation system. LRT consists of three carriages that capable to carry more than 600 passengers. In Indonesia, LRT is only available in two cities, Jakarta and Palembang. Nevertheless, until now the LRT only operates in Palembang. LRT is the public transportation that is useful for Palembang people. Initially, the construction of Light Rail Transit (LRT) in Palembang, South Sumatra was carried out not only to support the biggest sport event in Asia, the 18th Asian Games but also LRT is intended as the alternative transportation for people in their daily activity so that it can reduce the congestion and pollution due to the large number of motorized vehicles on the highway (Suryanti, 2018). It means that the construction of LRT is not only as the supporter of 18th Asian Games but also as the alternative to reduce the increase of traffic density in Palembang city. In Palembang, LRT starts operating on August 2018. When the first operating, LRT only has 6 stations. In the line with the expansion in public interest of LRT, this time LRT station is getting into 13 stations. LRT has 13 stations in some strategic points. Those stations are Sultan Mahmud Badaruddin II International Airport, Asrama Haji, Punti Kayu, RSUD, Garuda Dempo, Demang, Bumi Sriwijaya, Dishub, Cinde, Ampera, Polresta, Jakabaring and DJKA Station. -

Asia Urban Transport & Railway Engineering

ASIA URBAN TRANSPORT & RAILWAY ENGINEERING KOREA Osong (HSL): Independent verification Osong depot EGISMORE THAN 50 YEARS SERVING access signalling design THE URBAN TRANSPORT AND RAILWAY ENGINEERING SECTOR CHINA Macao (LRT): EPCM and technical assistance for the implementation of the 1st phase of Macao LRT system Wuhan-Guangzhou (HSL): Supervision of construction works on the Wuhan-Guangzhou high-speed line China (LRT Lines): Study of whole life cycle safe operation control & management system for modern tramway China (LRT lines): Consultancy services for tramway INDIA express design URBAN PROJECTS Chennai (MRT): General consultant, phase I Kolkata (MRT): General consultant Mumbai (MRT): General consultant on line 3 Nagpur (MRT): General consultant PHILIPPINES Pune (MRT): General consultant Kochi (MRT): Detail design consultant (viaducts and stations) Manila (LRT): Extension, independent consultant Delhi (MRT): Detail design consultant RAILWAY PROJECTS New Delhi (Freight Corridor): EMP4 contract - Design consultant SINGAPORE Delhi-Meerut (Rapid Rail Transit System): Detail design consultant Tuas (MRT): Trackwork design for Tuas-West depot extension Singapore (MRT): Trackbed and fastener system condition DELIVERED LOCALLY assessment - SMRT THAILAND Singapore (MRT): Consultancy services for catenary system - LTA Pink Line (monorail): Project consultant Orange Line (MRT): Project implementation consultant for east section Blue Line (MRT): Mechanical & electrical supervision consultant INDONESIA Green Line (MRT): Detailed design of viaduct -

COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT in SPORTS TOURISM DEVELOPMENT AS INCLUSIVE ECONOMIC DRIVER in SOUTH SUMATERA Zulkifli Harahap(1)

eISSN : 2654-4687 ; pISSN : 2654-3894 https://doi.org/10.17509/jithor.v3i2.28577 [email protected] http://ejournal.upi.edu/index.php/Jithor Volume 3, No. 2, October 2020 COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT IN SPORTS TOURISM DEVELOPMENT AS INCLUSIVE ECONOMIC DRIVER IN SOUTH SUMATERA Zulkifli Harahap(1), Titing Kartika(2)* (1) Politeknik Pariwisata Palembang (2) Sekolah Tinggi Ilmu Ekonomi Pariwisata YAPARI [email protected], [email protected] Submitted: 30 September 2020 Revised: 5 October 2020 Accepted: 15 October 2020 ABSTRACT The development of the concept of Sports Tourism in Palembang in South Sumatra has been a government program; in this case, the Ministry of Tourism, Republic of Indonesia. The concept was developed to see the potential that exists among Jakabaring Sport City, an integrated Smart Sports Eco Green Complex. The presence of community empowerment in this concept's development includes three aspects: enabling, empowering, and protecting. Meanwhile, Sports Tourism drives the economy inclusive due to it has associated benefits that can be perceived by the public either directly or indirectly. Such benefits include transform and boost economic growth, income generation, poverty reduction, and expanding access and opportunity. The study used a qualitative descriptive approach that is to carry out observation, interviews, and documentation. The results of this study indicate that the development of Sport Tourism has a positive impact on the empowerment of local communities. Keywords: Community Empowerment, Sport Tourism, Inclusive Economy, South Sumatera INTRODUCTION range of sporting activities, both national and Tourism is now an essential part of international sports events in Palembang and Indonesia's national development, even equipped with facilities.