Multimodal Approach to Treatment for Control of Fur Mites

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guidance on Identification of Alternatives to New Pops

Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants Guidance on identification of alternatives to new POPs Secretariat of the Stockholm Convention Concept of “Substitution” under the Stockholm Convention • The substitution is a strategy promoted by the Stockholm Convention to reach its objectives • Parties that are still producing or using the new POPs listed in Annex A, will need to search and identify alternatives to replace them • In the case of PFOS and for the exemptions for uses allowed by the Convention, these group of chemicals will be eventually prohibited and Parties are therefore encouraged to find alternatives to substitute them 2 Availability of alternatives • Currently, some countries have phased out the use of some of the new POPs, and there are feasible alternatives available to replace them Alternatives Chemical Name Use Ethoprop, oxamyl Pesticide to control banana root borer Cyfluthrin, Imidacloprid Pesticide to control tobacco wireworms Azadirachtin, bifenthrin, boric acid, carbaryl, Pesticide to control capsaicin, cypermethrin, cyfluthrin, ants and/or deltamethrin, diazinon, dichlorvos, cockroaches esfenvalerate, imidacloprid, lamda-cyhalothrin, Chlordecone malathion, permethrin, piperonyl butoxide, pyrethrins, pyriproxyfen, resmethrin, s- bioallerthrin, tetramethrin Bacillus thuringiensis, cultural practices such Pest management as crop rotation, intercropping, and trap cropping; barrier methods, such as screens, and bagging of fruit; use of traps such as pheromone and light traps to attract and kill insects. 3 -

Lindane – Product Discontinuation • the FDA Announced the Discontinuation of Lindane 1% Lotion and 1% Shampoo Due to Product Line Rationalization

Lindane – Product Discontinuation • The FDA announced the discontinuation of Lindane 1% lotion and 1% shampoo due to product line rationalization. — The discontinuation is not due to product quality, safety or efficacy concerns. • Lindane lotion is indicated for the treatment of scabies (infestations of Sarcoptes scabei) only in patients who cannot tolerate other approved therapies, or have failed treatment with other approved therapies. • Lindane shampoo is indicated for the treatment of head lice (infestations of Pediculus humanus capitis), crab lice (infestations of Pthirus pubis), and their ova only in patients who cannot tolerate other approved therapies, or have failed treatment with other approved therapies. • Other prescription products indicated to treat lice include Ulesfia® (benzyl alcohol) 5% lotion, Ovide® (malathion) 0.5% lotion, Natroba™ (spinosad) 0.9% topical suspension, and Sklice® (ivermectin) 0.5% lotion. — Over-the-counter products indicated to treat lice include various formulations of 1% permethrin (eg, Nix®), various formulations of piperonyl butoxide/pyrethrins (eg, CareOne® Lice), and other miscellaneous products such as Lycelle®. • Other prescription products indicated to treat scabies include Eurax® (crotamiton) 10% cream and 10% lotion and Elimite™ (permethrin) 5% cream. optumrx.com OptumRx® specializes in the delivery, clinical management and affordability of prescription medications and consumer health products. We are an Optum® company — a leading provider of integrated health services. Learn more at optum.com. All Optum® trademarks and logos are owned by Optum, Inc. All other brand or product names are trademarks or registered marks of their respective owners. This document contains information that is considered proprietary to OptumRx and should not be reproduced without the express written consent of OptumRx. -

Crotamiton, an Anti-Scabies Agent, Suppresses Histamine- and Chloroquine-Induced Itch Pathways in Sensory Neurons and Alleviates Scratching in Mice

Original Article Biomol Ther 28(6), 569-575 (2020) Crotamiton, an Anti-Scabies Agent, Suppresses Histamine- and Chloroquine-Induced Itch Pathways in Sensory Neurons and Alleviates Scratching in Mice Da-Som Choi1,2,†, Yeounjung Ji1,2,†, Yongwoo Jang3, Wook-Joo Lee1,2 and Won-Sik Shim1,2,* 1College of Pharmacy, Gachon University, Incheon 21936, 2Gachon Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Incheon 21936, 3Department of Biomedical Engineering, Hanyang University, Seoul 04736, Republic of Korea Abstract Crotamiton is an anti-scabies drug, but it was recently found that crotamiton also suppresses non-scabietic itching in mice. How- ever, the underlying mechanism is largely unclear. Therefore, aim of the study is to investigate mechanisms of the anti-pruritic effect of crotamiton for non-scabietic itching. Histamine and chloroquine are used as non-scabietic pruritogens. The effect of crota- miton was identified using fluorometric intracellular calcium assays in HEK293T cells and primary cultured dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons. Further in vivo effect was evaluated by scratching behavior tests. Crotamiton strongly inhibited histamine-induced calcium influx in HEK293T cells, expressing both histamine receptor 1 (H1R) and transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1), as a model of histamine-induced itching. Similarly, it also blocked chloroquine-induced calcium influx in HEK293T cells, express- ing both Mas-related G-protein-coupled receptor A3 (MRGPRA3) and transient receptor potential A1 (TRPA1), as a model of histamine-independent itching. Furthermore, crotamiton also suppressed both histamine- and chloroquine-induced calcium influx in primary cultures of mouse DRG. Additionally, crotamiton strongly suppressed histamine- and chloroquine-induced scratching in mice. Overall, it was found that crotamiton has an anti-pruritic effect against non-scabietic itching by histamine and chloroquine. -

TITLE: Lindane and Other Treatments for Lice and Scabies: a Review of Clinical Effectiveness and Safety

TITLE: Lindane and Other Treatments for Lice and Scabies: A Review of Clinical Effectiveness and Safety DATE: 11 June 2010 CONTEXT AND POLICY ISSUES: Head lice infestation (Pediculosis capitis) affects millions of children and adults worldwide each year.1 Direct head-to-head contact is the most common mode of transmission.2 The highest prevalence of infestation occurs in school aged children aged three to eleven years, with girls being more commonly affected than boys.1,2 Although head lice are not generally associated with serious morbidity, they are responsible for significant social embarrassment and lost productivity in schools or offices.1 Scabies, an infestation of the skin by the mite Sarcoptes scabiei, represents a common public health concern particularly in overcrowded communities with a high prevalence of poverty.3 Scabies is transmitted by close-person contact and occasionally by clothing or linens.3 Complications include secondary bacterial infections and post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis.3 Topical products available in Canada for the treatment of head lice and scabies are presented in Appendix 1 and Appendix 2. Insecticidal agents such as permethrin and lindane have historically been considered the standard treatments for head lice and scabies.2,3 Toxicity is low following topical administration of permethrin due to minimal percutaneous absorption.4 However, several jurisdictions have banned lindane due to concerns of neurotoxicity and bone marrow suppression, as well as potential negative effects on the environment (contamination of waste water).5 Furthermore, widespread use of permethrin, pyrethrins/piperonyl butoxide, and lindane has led to resistance and higher rates of treatment failure.6 Resistance patterns and rates to these agents in Canada have not yet been studied.6 Due to concerns surrounding resistance and neurotoxicity, patients and caregivers have searched for alternative treatments. -

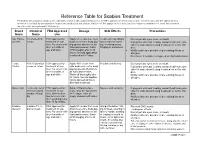

Reference Table for Scabies Treatment Permethrin and Crotamiton Products Are Commonly Used Over-The-Counter Products That Are FDA Approved Treatments for Scabies

Reference Table for Scabies Treatment Permethrin and crotamiton products are commonly used over-the-counter products that are FDA approved treatments for scabies. Invermectin is an FDA approved treat- ment that is available by prescription in both an oral medication and a lotion. Lindane is FDA approved for scabies but is no longer recommended as a first-line treatment for scabies due to its potential CNS toxicity. Brand Chemical FDA Approved Dosage Side Effects Precautions Name Name Use Nix, Elimite, 5% Permethrin FDA approved for Apply 5% cream from neck Treatment may initially Do not get into eyes, nose, or mouth Generic cream treatment of sca- down over entire body pay- make redness, swell- If pregnant or breast feeding, consult health care pro- bies. For use in chil- ing special attention to all ing, or itching worse. vider for instructions if using treatment on self or chil- dren 2 months of folds and creases. Wash Tingling or numbness. dren. age and older. off thoroughly after 8-14 Notify health care provider of pre-existing illness or hours. Second application allergies. is advised after 7 days. Do not use if sensitive to ragweed or chrysanthemums. Eurax, 10% Crotamiton FDA approved for Apply 10% cream from Irritation and itching Do not get into eyes, nose or mouth Crotan cream or lotion treatment of sca- chin down over entire body If pregnant or breast feeding, consult health care pro- bies. For use in chil- paying special attention to vider for instructions if using treatment on self or chil- dren 6 months of all folds and creases. -

Therapeutic Class Overview Scabicides and Pediculicides

Therapeutic Class Overview Scabicides and Pediculicides Therapeutic Class Overview/Summary: The agents indicated for the management of scabies and head lice are listed in Table 1. The skin and mucous membrane scabicides and pediculicides are approved to treat pediculosis and scabies.1-10 Pediculosis is a transmissible infection, which is caused by three different kinds of lice depending on the location: head (Pediculus humanus capitis), body (Pediculus humanus corporis) and pubic region (Phthirus pubis). Pediculosis is often asymptomatic; however, itching may occur due to hypersensitivity to lice saliva.11 Scabies is also a transmissible skin infection caused by the mite Sarcoptes scabiei. Mites burrow into the skin and lay eggs, which when hatched, will crawl to the skin’s surface and begin to make new burrows. The most common clinical manifestation of scabies is itching, which is due to a hypersensitivity reaction to the mite or mite excrement.12 When treating scabies and lice, the goal of therapy is to eradicate the parasite. Benzyl alcohol inhibits lice from closing their respiratory spiracles, which causes the lice to asphyxiate.3 Crotamiton has scabicidal and antipruritic actions; however, the exact mechanism of action is unknown.4 Lindane is a central nervous system stimulant, which causes convulsions and death of the arthropod.1,2 Malathion is an organophosphate agent, which inhibits cholinesterase activity.5 Permethrin disrupts the sodium channel current, which leads to delayed repolarization and paralysis of the arthropod.1,2 Spinosad causes neuronal excitation, which leads to paralysis and death.6 The suspension also contains an unspecified amount of benzyl alcohol. -

Therapeutic Class Overview Scabicides and Pediculicides

Therapeutic Class Overview Scabicides and Pediculicides Therapeutic Class Overview/Summary: The agents indicated for the management of scabies and head lice are listed in Table 1. All of these agents are Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved for the treatment of head lice with the exception of crotamiton (Eurax®), which is only indicated to treat scabies.1-8 The scabicides and pediculicides have a neurotoxic effect on lice and scabies, resulting in periods of central nervous system hyperexcitation, ultimately resulting in paralysis and death of the parasite.1-8 Benzyl alcohol (Ulesfia®) is unique in that it disables the breathing structure of the lice, resulting in asphyxiation rather than neuroexcitation.1 The challenge of complete eradication of the infestation with a single treatment results from the fact that the neurotoxic insecticides rely on the nervous system to exert their effect; therefore, newborn larvae are not susceptible to these agents as they do not have intact nervous systems for several days after eggs are hatched. Pyrethrins (RID®) and permethrin (Nix®) are pediculicidal, but not ovicidal, and require nit combing and retreatment in 7 to 10 days. Resistance to pyrethrins and permethrin has been reported to be increasing in the United States. Benzyl alcohol is not ovicidal and also requires a second treatment, but resistance is unlikely due to its unique mechanism of action. Malathion is both pediculicidal and ovicidal, but must be applied for 8 to 12 hours, and is highly flammable. Lindane is neurotoxic and is not recommended as an initial treatment option.9 Ivermectin (Sklice®) and spinosad (Natroba®) are recently approved products that are pediculicidal but not ovicidal. -

Therapeutic Drug Class

EFFECTIVE Version Department of Vermont Health Access Updated: 06/05/20 Pharmacy Benefit Management Program /2016 Vermont Preferred Drug List and Drugs Requiring Prior Authorization (includes clinical criteria) The Commissioner for Office of Vermont Health Access shall establish a pharmacy best practices and cost control program designed to reduce the cost of providing prescription drugs, while maintaining high quality in prescription drug therapies. The program shall include: "A preferred list of covered prescription drugs that identifies preferred choices within therapeutic classes for particular diseases and conditions, including generic alternatives" From Act 127 passed in 2002 The following pages contain: • The therapeutic classes of drugs subject to the Preferred Drug List, the drugs within those categories and the criteria required for Prior Authorization (P.A.) of non-preferred drugs in those categories. • The therapeutic classes of drugs which have clinical criteria for Prior Authorization may or may not be subject to a preferred agent. • Within both categories there may be drugs or even drug classes that are subject to Quantity Limit Parameters. Therapeutic class criteria are listed alphabetically. Within each category the Preferred Drugs are noted in the left-hand columns. Representative non- preferred agents have been included and are listed in the right-hand column. Any drug not listed as preferred in any of the included categories requires Prior Authorization. Approval of non-preferred brand name products may require trial and failure of at least 2 different generic manufacturers. GHS/Change Healthcare Change Healthcare GHS/Change Healthcare Sr. Account Manager: PRESCRIBER Call Center: PHARMACY Call Center: Michael Ouellette, RPh PA Requests PA Requests Tel: 802-922-9614 Tel: 1-844-679-5363; Fax: 1-844-679-5366 Tel: 1-844-679-5362 Fax: Note: Fax requests are responded to within 24 hrs. -

Federal Register / Vol. 60, No. 80 / Wednesday, April 26, 1995 / Notices DIX to the HTSUS—Continued

20558 Federal Register / Vol. 60, No. 80 / Wednesday, April 26, 1995 / Notices DEPARMENT OF THE TREASURY Services, U.S. Customs Service, 1301 TABLE 1.ÐPHARMACEUTICAL APPEN- Constitution Avenue NW, Washington, DIX TO THE HTSUSÐContinued Customs Service D.C. 20229 at (202) 927±1060. CAS No. Pharmaceutical [T.D. 95±33] Dated: April 14, 1995. 52±78±8 ..................... NORETHANDROLONE. A. W. Tennant, 52±86±8 ..................... HALOPERIDOL. Pharmaceutical Tables 1 and 3 of the Director, Office of Laboratories and Scientific 52±88±0 ..................... ATROPINE METHONITRATE. HTSUS 52±90±4 ..................... CYSTEINE. Services. 53±03±2 ..................... PREDNISONE. 53±06±5 ..................... CORTISONE. AGENCY: Customs Service, Department TABLE 1.ÐPHARMACEUTICAL 53±10±1 ..................... HYDROXYDIONE SODIUM SUCCI- of the Treasury. NATE. APPENDIX TO THE HTSUS 53±16±7 ..................... ESTRONE. ACTION: Listing of the products found in 53±18±9 ..................... BIETASERPINE. Table 1 and Table 3 of the CAS No. Pharmaceutical 53±19±0 ..................... MITOTANE. 53±31±6 ..................... MEDIBAZINE. Pharmaceutical Appendix to the N/A ............................. ACTAGARDIN. 53±33±8 ..................... PARAMETHASONE. Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the N/A ............................. ARDACIN. 53±34±9 ..................... FLUPREDNISOLONE. N/A ............................. BICIROMAB. 53±39±4 ..................... OXANDROLONE. United States of America in Chemical N/A ............................. CELUCLORAL. 53±43±0 -

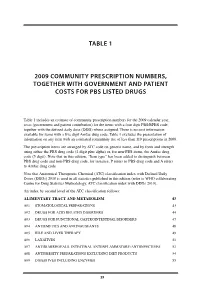

Table 1 2009 Community Prescription Numbers

TABLE 1 2009 COMMUNITY PRESCRIPTION NUMBERS, TOGETHER WITH GOVERNMENT AND PATIENT COSTS FOR PBS LISTED DRUGS Table 1 includes an estimate of community prescription numbers for the 2009 calendar year, costs (government and patient contribution) for the items with a four digit PBS/RPBS code, together with the defined daily dose (DDD) where assigned. There is no cost information available for items with a five digit Amfac drug code. Table 1 excludes the presentation of information on any item with an estimated community use of less than 110 prescriptions in 2009. The prescription items are arranged by ATC code on generic name, and by form and strength using either the PBS drug code (4 digit plus alpha) or, for non-PBS items, the Amfac drug code (5 digit). Note that in this edition, “Item type” has been added to distinguish between PBS drug code and non-PBS drug code, for instance, P refers to PBS drug code and A refers to Amfac drug code. Note that Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification index with Defined Daily Doses (DDDs) 2010 is used in all statistics published in this edition (refer to WHO collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology, ATC classification index with DDDs 2010). An index by second level of the ATC classification follows: ALIMENTARY TRACT AND METABOLISM 43 A01 STOMATOLOGICAL PREPARATIONS 43 A02 DRUGS FOR ACID RELATED DISORDERS 44 A03 DRUGS FOR FUNCTIONAL GASTROINTESTINAL DISORDERS 47 A04 ANTIEMETICS AND ANTINAUSEANTS 48 A05 BILE AND LIVER THERAPY 49 A06 LAXATIVES 51 A07 ANTIDIARRHOEALS, INTESTINAL ANTIINFLAMMATORY/ANTIINFECTIVES -

Q What Is the Most Effective Treatment for Scabies?

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network CLINICAL INQUIRIES ONLINE EXCLUSIVE Jonathon J. Campbell, MD; Christopher P. Q What is the most effective Paulson, MD, FAAFP United States Air Force Eglin Family Medicine Residency, treatment for scabies? Fla Joan Nashelsky, MLS EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER University of Iowa, Iowa City Topical permethrin is the most Although not as effective as topical DEPUTY EDITOR A effective treatment for classic sca- permethrin, oral ivermectin is an effective Rick Guthmann, MD, MPH bies (strength of recommendation [SOR]: treatment compared with placebo (SOR: B, Advocate Illinois Masonic A, meta-analyses with consistent results). a single small randomized trial). Family Medicine Residency, Topical lindane and crotamiton are in- Oral ivermectin may reduce the preva- Chicago ferior to permethrin but appear equivalent lence of scabies at one year in populations to each other and benzyl benzoate, sulfur, with endemic disease more than topical and natural synergized pyrethrins (SOR: B, permethrin (SOR: B, a single randomized limited randomized trials). trial). Evidence summary tients) showed no difference in treatment A 2007 Cochrane review on scabies treatment failures, but the trials were small and lacked identified 11 trials that evaluated permethrin sufficient statistical power. for treating scabies.1 In 2 trials, 140 patients Four additional studies included in were randomized to receive either 200 mcg/kg the review compared crotamiton with lin- of oral ivermectin or overnight application of dane (100 patients), lindane with sulfur 5% topical permethrin. Topical permethrin (68 patients), benzyl benzoate with sulfur was superior to oral ivermectin with failure (158 patients), and benzyl benzoate with rates at 2 weeks of 8% and 39%, respectively natural synergized pyrethrins (240 patients). -

Potential Chemical Contaminants in the Marine Environment

Potential chemical contaminants in the marine environment An overview of main contaminant lists Victoria Tornero, Georg Hanke 2017 EUR 28925 EN This publication is a Technical report by the Joint Research Centre (JRC), the European Commission’s science and knowledge service. It aims to provide evidence-based scientific support to the European policymaking process. The scientific output expressed does not imply a policy position of the European Commission. Neither the European Commission nor any person acting on behalf of the Commission is responsible for the use that might be made of this publication. Contact information Name: Victoria Tornero Address: European Commission Joint Research Centre, Directorate D Sustainable Resources, Water and Marine Resources Unit, Via Enrico Fermi 2749, I-21027 Ispra (VA) Email: [email protected] Tel.: +39-0332-785984 JRC Science Hub https://ec.europa.eu/jrc JRC 108964 EUR 28925 EN PDF ISBN 978-92-79-77045-6 ISSN 1831-9424 doi:10.2760/337288 Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2017 © European Union, 2017 The reuse of the document is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged and the original meaning or message of the texts are not distorted. The European Commission shall not be held liable for any consequences stemming from the reuse. How to cite this report: Tornero V, Hanke G. Potential chemical contaminants in the marine environment: An overview of main contaminant lists. ISBN 978-92-79-77045-6, EUR 28925, doi:10.2760/337288 All images © European Union 2017 Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................................ 1 Abstract ............................................................................................................... 2 1 Introduction ...................................................................................................... 3 2 Compilation of substances of environmental concern .............................................