Nostalgia ON: Sounds Evoking the Zeitgeist of the Eighties

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jall 20 Great Extended Play Titles Available in June

KD 9NoZ ! LO9O6 Ala ObL£ it sdV :rINH3tID AZNOW ZHN994YW LIL9 IOW/ £L6LI9000 Heavy 906 ZIDIOE**xx***>r****:= Metal r Follows page 48 VOLUME 99 NO. 18 THE INTERNATIONAL NEWSWEEKLY OF MUSIC AND HOME ENTERTAINMENT May 2, 1987/$3.95 (U.S.), $5 (CAN.) Fla. Clerk Faces Obscenity Radio Wary of Indecent' Exposure Charge For Cassette Sale FCC Ruling Stirs Confusion April 20. She was charged with vio- BY CHRIS MORRIS lating a state statute prohibiting ington, D.C., and WYSP Philadel- given further details on what the LOS ANGELES A Florida retail "sale of harmful material to a per- BY KIM FREEMAN phia, where Howard Stern's morn- new guidelines are, so it's literally store clerk faces felony obscenity son under the age of 18," a third -de- NEW YORK Broadcasters are ex- ing show generated the complaints impossible for me to make a judg- charges for selling a cassette tape gree felony that carries a maximum pressing confusion and dismay fol- that appear to have prompted the ment on them as a broadcaster." of 2 Live Crew's "2 Live Crew Is penalty of five years in jail or a lowing the Federal Communications FCC's new guidelines. According to FCC general coun- What We Are" to a 14- year -old. As a $5,000 fine. Commission's decision to apply a "At this point, we haven't been (Continued on page 78) result of the case, the store has The arrest apparently stems from broad brush to existing rules defin- closed its doors. the explicit lyrics to "We Want ing and regulating the use of "inde- Laura Ragsdale, an 18- year -old Some Pussy," a track featured on cent" and /or "obscene" material on part-time clerk at Starship Records the album by Miami-based 2 Live the air. -

Girlschool: »Es Ist Zeit Für Die Revolution« Wir Sprachen Mit Sängerin/Gitarristin Kim Mcauliffe Düsseldorf. (IT)

Girlschool Interview Girlschool: »Es ist Zeit für die Revolution« Wir sprachen mit Sängerin/Gitarristin Kim McAuliffe Düsseldorf. (IT). Bereits 1981 veröffentlichten sie ihr Durchbruchsalbum »Hit And Run«. Und obwohl die Mädels von Girlschool die magische 50 auf der Altersskala mittlerweile schon etwas länger hinter sich gelassen haben, werden sie wohl für alle Zeiten als »Motörheads kleine Schwestern« gehandelt werden. Das weiß auch Sängerin/Gitarristin Kim McAuliffe, die wir kurz vor dem Start einer Tour zum Gespräch bitten, die für viele Rock- und Metal-Fans der Inbegriff der Erfüllung sein dürfte: Motörhead, Saxon und eben Girlschool (17. November – Düsseldorf, Mitsubishi-Electric-Halle). Gut, dass Girlschools neues Album »Guilty As Sin« eine Großtat geworden ist, die viele nicht mehr für möglich gehalten hätten. Dementsprechend blendend aufgelegt ist die gute Kim auch im WochenPost-Interview. Hey Kim, ihr seid kurz davor, wieder mit Euren langjährigen Kumpels von Motörhead und Saxon auf Tour zu gehen. Was kommt dir zuerst in den Sinn, wenn du an dieses berüchtigte Package denkst? Wir fühlen uns wirklich sehr geehrt, auf dieser Tour zu Motörheads 40. Geburtstag spielen zu dürfen. Vor allem, weil wir sie schon auf ihrer allerersten England-Tour supportet haben. Das war 1979, nachdem Lemmy und Co. „Overkill" herausgebracht hatten, stell‘ dir das mal vor. Na ja, und dass die Jungs von Saxon dabei sind, macht das Ganze noch spezieller. Würde ich nicht zufällig mitspielen – ich wäre hingegangen, haha. Einige der Fans, die zu den Shows kommen werden, waren sicherlich schon vor dreieinhalb Jahrzehnten dabei. Seitdem hat sich im Musikgeschäft viel geändert. Denkst du, dass die drei legendären Bands den Spirit von früher einfangen und transportieren können? Auf jeden Fall, denn ich denke, das Line Up ist immer noch der Hammer. -

Black Sabbath the Complete Guide

Black Sabbath The Complete Guide PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Mon, 17 May 2010 12:17:46 UTC Contents Articles Overview 1 Black Sabbath 1 The members 23 List of Black Sabbath band members 23 Vinny Appice 29 Don Arden 32 Bev Bevan 37 Mike Bordin 39 Jo Burt 43 Geezer Butler 44 Terry Chimes 47 Gordon Copley 49 Bob Daisley 50 Ronnie James Dio 54 Jeff Fenholt 59 Ian Gillan 62 Ray Gillen 70 Glenn Hughes 72 Tony Iommi 78 Tony Martin 87 Neil Murray 90 Geoff Nicholls 97 Ozzy Osbourne 99 Cozy Powell 111 Bobby Rondinelli 118 Eric Singer 120 Dave Spitz 124 Adam Wakeman 125 Dave Walker 127 Bill Ward 132 Related bands 135 Heaven & Hell 135 Mythology 140 Discography 141 Black Sabbath discography 141 Studio albums 149 Black Sabbath 149 Paranoid 153 Master of Reality 157 Black Sabbath Vol. 4 162 Sabbath Bloody Sabbath 167 Sabotage 171 Technical Ecstasy 175 Never Say Die! 178 Heaven and Hell 181 Mob Rules 186 Born Again 190 Seventh Star 194 The Eternal Idol 197 Headless Cross 200 Tyr 203 Dehumanizer 206 Cross Purposes 210 Forbidden 212 Live Albums 214 Live Evil 214 Cross Purposes Live 218 Reunion 220 Past Lives 223 Live at Hammersmith Odeon 225 Compilations and re-releases 227 We Sold Our Soul for Rock 'n' Roll 227 The Sabbath Stones 230 Symptom of the Universe: The Original Black Sabbath 1970–1978 232 Black Box: The Complete Original Black Sabbath 235 Greatest Hits 1970–1978 237 Black Sabbath: The Dio Years 239 The Rules of Hell 243 Other related albums 245 Live at Last 245 The Sabbath Collection 247 The Ozzy Osbourne Years 249 Nativity in Black 251 Under Wheels of Confusion 254 In These Black Days 256 The Best of Black Sabbath 258 Club Sonderauflage 262 Songs 263 Black Sabbath 263 Changes 265 Children of the Grave 267 Die Young 270 Dirty Women 272 Disturbing the Priest 273 Electric Funeral 274 Evil Woman 275 Fairies Wear Boots 276 Hand of Doom 277 Heaven and Hell 278 Into the Void 280 Iron Man 282 The Mob Rules 284 N. -

Randy Rhoads 06.09.1956 - 19.03.1982

Randy Rhoads 06.09.1956 - 19.03.1982 Koostaja Kaur Maran 8b 1 Eddie Van Halen : Randy Rhoads was one guitarist who was honest and very good. I feel so sorry for him, but you never know--he might be up there right now, jammin' with John Bonham and everyone else. 2 Algus, varasemad aastad Randall William Rhoads sündis kuuendal septembril 1956. aastal St.Johni haiglas Santa Monicas, Kalifornias. Tal oli vanem vend Doug ja õde Kathy, Randy oli noorim. Isa William Arthur Rhoads, kes oli koolis muusikaõpetaja, jättis pere maha kui Randy oli ainult 18 kuud vana. Ema Delores Rhoads pidi lapsi üksinda kasvatama. Hiljem isa abiellus uuesti ja sündisid Randy poolvennad Dan ja Paul. Randy oli umbes kuue või seitsme aasta vanune kui ta hakkas õppima kitarrimängu Põhja-Hollywoodi Musonia nimelises muusikakoolis, mis oli tema ema oma. Randy esimene kitarr oli akustiline Gibson, mis oli kuulunud tema ema isale, Randy vanaisale. Randy ja ta õde Kathy hakkasid võtma folk-kitarri tunde ja Randy ka klaveritunde (seda viimast nõudis tema ema, kes tahtis, et poiss õpiks nooti lugema. Klaveritunnid ei kestnud väga kaua. 12-aastaselt tekkis temas huvi rock-kitarri vastu. Delores Rhoadsil oli olemas vana Harmony Rocket poolakustiline kitarr, mis oli sel ajal peaaegu sama suur kui poiss ise. Peaaegu aasta õpetas Randyt Scott Shelly, Randy ema kooli kitarriõpetaja. Lõpuks läks mees rääkima oma õpilase emaga ja ütles, et ta ei saa poissi edasi õpetada kuna too teadis juba niigi kõike, mida õpetaja. 11 aasta vanuselt kohtus Rhoads oma parima sõbra Kelly Garniga. Randy oli alati teistest erinev, ta kandis erinevaid rõivaid jne. -

Our Underground Power Records Rival Silver Pressed CD Release Incl

First Assault 2019 ! Traveler Vinyl was sold out in pre-order, the repress will follow in 2 weeks ! Our Underground Power Records Rival silver pressed CD release incl. lyrics will hopefully arrive in 2 weeks ! Brandnew Underground Power Records CD + VINYL Releases - 3 x NWOTHM ! FRENZY - Blind Justice (NEW*LIM.500 CD*SPA HEAVY METAL*RACER X*RIOT*JUDAS PRIEST) – 13 € Underground Power Records 2019 - Brandnew limited Edition CD - 500 copies only ! Incl. Killer 16 - pages Comic Artwork / Booklet ! For Fans of Racer X, Riot, Heavy Load, Judas Priest, Malice, Scorpions, Dokken, Accept, Lizzy Borden Fantastic Mix between Speed Metal and melodic old school 80's Hard Rock ! Awesome Vocals, a pounding rhythm section and unbelievable great guitar riffs and solo wizardry ! KAINE – A Crisis of Faith (NEW*LIM.500 CD*BRITISH STEEL*IRON MAIDEN*MONUMENT+3 BONUS) - 13 € Underground Power Records 2019 – Brandnew Limited Edition of 500 copies CD – British Steel at its best ! Finally as real Silver pressed CD incl. 3 Bonus Tracks ! Cover Artwork by Alan Lathwell ! For Fans of early Iron Maiden (DiAnno), Judas Priest, Dark Forest, Monument This is Kaine's new album A CRISIS OF FAITH the first full length release from the line-up that features Rage Sadler (Guitars and Vocals), Chris MacKinnon (Drums, Keys, and Vocals), Saxon Davids (Lead Guitar and Backing Vocals) and Stephen Ellis (Bass and Backing Vocals). The new release features songs written by all four bands members and has been a collaborative effort. The album has been written and rehearsed since August 2015. OATH - Legion (NEW*LIM.500 CD*EPIC NWOBHM*LEGEND*ANGEL WITCH*MAGNESIUM) – 11 € Underground Power Records 2019 – Brandnew Limited Edition of 500 copies CD – British Steel at its best ! 4 Page Booklet incl. -

NEW RELEASE GUIDE October 2 October 9 ORDERS DUE AUGUST 28 ORDERS DUE SEPTEMBER 4

ada–music.com @ada_music NEW RELEASE GUIDE October 2 October 9 ORDERS DUE AUGUST 28 ORDERS DUE SEPTEMBER 4 2020 ISSUE 21 October 2 ORDERS DUE AUGUST 28 ALOE BLACC ALL LOVE EVERYTHING In the years since Aloe Blacc’s last album, The Grammy nominated “Lift Your Spirit”, the global superstar spent time working on an even dearer project: his family. All Love Everything, his upcoming album, is the singer-songwriter’s first collection of material written as a father, a journey that’s expanded Blacc’s already heartfelt artistic palette. “Becoming a father made me want to share those experiences in music,” he says, admitting it’s a challenge to translate such a powerful All Love Everything is a generous addition to the thing into lyrics and melody. But the listeners who have A.I.M. catalog. It fulfills Blacc’s ambition to express the followed Blacc over the course of his career know that richness of familial love on songs like “Glory Days” and his facility with language and sound is deep – if anyone “Family,” while also making room for anthems about was up to the task, it’s him. perseverance and support like “My Way” and “Corner.” Working with producers Jonas Jeberg, Jugglerz, Jon Across three albums, his sound evolved and grew, Levine, and Matt Prime, Blacc has crafted his most finding a pocket that reflects the long and beautiful open-hearted album to date. Generous and warm, history of American soul with timeless, descriptive All Love Everything draws on soul, folk, and songwriting that speaks to the broad range of human contemporary pop, reminding listeners that there’s experience, from platonic love to love for humanity, from no pigeonholing the human experience. -

THE GARY MOORE DISCOGRAPHY (The GM Bible)

THE GARY MOORE DISCOGRAPHY (The GM Bible) THE COMPLETE RECORDING SESSIONS 1969 - 1994 Compiled by DDGMS 1995 1 IDEX ABOUT GARY MOORE’s CAREER Page 4 ABOUT THE BOOK Page 8 THE GARY MOORE BAND INDEX Page 10 GARY MOORE IN THE CHARTS Page 20 THE COMPLETE RECORDING SESSIONS - THE BEGINNING Page 23 1969 Page 27 1970 Page 29 1971 Page 33 1973 Page 35 1974 Page 37 1975 Page 41 1976 Page 43 1977 Page 45 1978 Page 49 1979 Page 60 1980 Page 70 1981 Page 74 1982 Page 79 1983 Page 85 1984 Page 97 1985 Page 107 1986 Page 118 1987 Page 125 1988 Page 138 1989 Page 141 1990 Page 152 1991 Page 168 1992 Page 172 1993 Page 182 1994 Page 185 1995 Page 189 THE RECORDS Page 192 1969 Page 193 1970 Page 194 1971 Page 196 1973 Page 197 1974 Page 198 1975 Page 199 1976 Page 200 1977 Page 201 1978 Page 202 1979 Page 205 1980 Page 209 1981 Page 211 1982 Page 214 1983 Page 216 1984 Page 221 1985 Page 226 2 1986 Page 231 1987 Page 234 1988 Page 242 1989 Page 245 1990 Page 250 1991 Page 257 1992 Page 261 1993 Page 272 1994 Page 278 1995 Page 284 INDEX OF SONGS Page 287 INDEX OF TOUR DATES Page 336 INDEX OF MUSICIANS Page 357 INDEX TO DISCOGRAPHY – Record “types” in alfabethically order Page 370 3 ABOUT GARY MOORE’s CAREER Full name: Robert William Gary Moore. Born: April 4, 1952 in Belfast, Northern Ireland and sadly died Feb. -

The Rising Stars CD

™ THEmusicINDEX www.themusicindex.com Get Ready to ROCK! The Rising Stars CD Featuring 16 upcoming, and independent artists To coincide with its sponsorship of the UK's Cambridge Rock Festival Second Stage (August 2007), music website Get Ready to ROCK! (GRTR!) has released ‘The Rising Stars’, a special edition CD showcasing some of the new music championed by it. GRTR! has promoted upcoming and independent bands along with the more established and mainstream since launch in 2003. The site attracts over 200,000 unique visitors per month with its wide range of news, reviews and interviews. Project co-ordinator David Randall comments: "We' ve promoted new talent from the very start and always wanted to provide a higher profile for those bands who are either unsigned or remaining independent. "We wanted the album to not only act as a showcase for upcoming talent but to reflect the range of music we promote on the site. However, we’ve aimed to produce a CD sampler where the music is complementary rather than one that contains a diverse range of music styles which doesn’t always work in terms of a good listen." "The unifying factor is that all the bands are independent or unsigned," says David. Some, like Stormzone and Sacred Heart, have been around for several years and built up a steady following on the live circuit. Others may be less familiar. Natascha Sohl first came to the website’s attention in 2004. "She has recently been working with a top-notch American publishing and production company. Her second album, due in early 2008, is touted as the one which will break her to a much bigger audience." 34 Coniston Road, Neston, South Wirral, Cheshire. -

Entertainment Memorabilia Entertainment

Montpelier Street, London I 17 December 2019 Montpelier Street, Entertainment Memorabilia Entertainment Entertainment Memorabilia I Montpelier Street, London I 17 December 2019 25432 Entertainment Memorabilia Montpelier Street, London | 17 December 2019 at 2pm BONHAMS ENQUIRIES SALE NUMBER: REGISTRATION Montpelier Street Claire Tole-Moir 25432 IMPORTANT NOTICE Knightsbridge, +44 (0) 20 7393 3984 Please note that all customers, London SW7 1HH [email protected] CATALOGUE: irrespective of any previous activity www.bonhams.com £15 with Bonhams, are required to Stephen Maycock complete the Bidder Registration +44 (0) 20 7393 3844 Form in advance of the sale. The VIEWING PRESS ENQUIRIES [email protected] form can be found at the back of Sunday 15 December [email protected] every catalogue and on our 10am to 4pm Aimee Clark website at www.bonhams.com Monday 16 December +44 (0) 20 7393 3871 CUSTOMER SERVICES and should be returned by email or 9am to 7pm [email protected] Monday to Friday post to the specialist department Tuesday 17 December 8.30am – 6pm or to the bids department at 9am to 12pm +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 [email protected] BIDS Guitar Highlights at HMV’s +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 Please see back of catalogue To bid live online and / or The Vault, Birmingham: +44 (0) 20 7447 7401 fax for important notice to bidders leave internet bids please go to Saturday 23 November [email protected] www.bonhams.com/auctions/25432 11am to 4pm ILLUSTRATIONS and click on the Register to bid link Sunday 24 November To bid via the internet please visit at the top left of the page. -

UNIVERSAL MUSIC • Paul Anka – Songs of December • the Who

• Paul Anka – Songs Of December • The Who – Quadrophenia The Directors Cut • Ozzy Osbourne – God Bless Ozzy Osbourne New Releases From Classics And Jazz Inside!! And more… UNI11-45 “Our assets on-line” UNIVERSAL MUSIC 2450 Victoria Park Ave., Suite 1, Willowdale, Ontario M2J 5H3 Phone: (416) 718.4000 Artwork shown may not be final UNIVERSAL MUSIC CANADA NEW RELEASE Short Sell Cycle Short Sell Cycle Artist/Title: Hedley / Storms Artist/Title: Hedley / Storms (Limited Edition Versions) Standard Cat. #: 0252777603 Dlx Edition Cat. #: 0252786782 Limited Edition FanPack Limited Edition Picture Disc Cat. #: 0252787837 Vinyl Cat. #: 0252757349 Standard Cat Price Code: SP Deluxe Ed. Price Code: SPS Standard Cat Price Code: U Deluxe Ed. Price Code: PP Standard UPC: Deluxe Edition UPC: Standard UPC: Deluxe Edition UPC: 6 02527 77603 3 6 02527 86782 3 6 02527 87837 9 6 02527 57349 6 Order Due: October 20, 2011 Order Due: October 20, 2011 Order Due: October 20, 2011 Order Due: October 20, 2011 Release Date: Nov. 8, 2011 Release Date: Nov. 8, 2011 Release Date: Nov. 8, 2011 Release Date: Nov. 8, 2011 File: Pop Genre Code: 33 Box Lot: 25 File: Pop Genre Code: 33 Box Lot: 25 Vancouver Chart-Topping Rockers HEDLEY return with STORMS! Vancouver Chart-Topping Rockers HEDLEY return with STORMS! The follow up to their multi-platinum album The Show Must Go (2009), the band’s fourth studio The follow up to their multi-platinum album The album STORMS includes the brand new hit single Show Must Go (2009), the band’s fourth studio “Invincible” – their biggest debuting single to date! album STORMS includes the brand new hit single “Invincible” – their biggest debuting single to date! Major advertising campaign (television, on-line, print, radio, outdoor) all set to roll out in the coming weeks. -

Hard-1993-02-26.Pdf

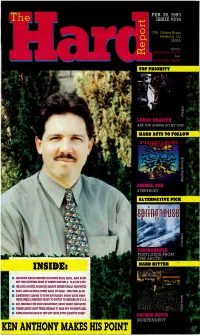

FEB. 26, 1993 -1-1 ISSUE #314 TOP PRIORITY ARE YOU GONNA GO MY WAY rt. HARD ACTS TO FOLLO W INIMALI BAG EVERYBODY ALTERNATIVE PICK ÉRINW10 POSTCARDS FRO M THE ARCTIC INSIDE: HARD HITTER • HIS ROCK RADIO RESUME INCLUDES KSJO, KLOL, AND KLOS BUT THE CUTTING EDGE IS WHERE OUR MR A. IS AT IN 1993 II THE LONG AWAITED SHAMROCK 'MALRITE MERGER FINALLY ANNOUNCED • KSD'S JOHN McCRAE COMES BACK TO KRQR - THIS TIME AS PD. MI SOMETHING'S COMING TO TOWN BUT NOBODY KNOWS QUITE WHAT: WEGX/PHILLY RUMORED READY TO SWITCH TO MODERN OR C.O.R. la RCA REMODELS THE ROCK DEPARTMENT, MINUS HARDY AND GATES • FORMER GENTLE GIANT DEREK SHULMAN TO HEAD NEW WB/GIANT LABEL • WKFM ,SYRACUSE LMAD BY NEW CITY (WSYR,WYYY) COUNTRY'S COEN' '"71I REICH INDEPENDENT KEN ANTHONY MAKES HIS POINT "Just Another Night" is not c‘• just another song. JUDE C OLE Just Another Night" the new track from Start The Car. Produced by Jude Cole and James Newton Howard Mixed by Chris Lord-Alge Personal Management: Ed Leftler/E.L. Management, Inc. 01993 Reprise Records. Background Vocals: Sammy Llanas (BoDeans) 9 Hard Hundredt LW TW Artist ka_a LW TW Artist Track 5 1 Coverdale/Page "Pride And Joy" IA 92 50 10,000 Maniacs "Candy ..." t2 2 Van Halen "Won't Get ..." 4 3 R.E.M "Man On The Moon" 1 4 Mick Jagger "Don't Tex Me Up" A 6 5 Stin s "If I Ever Lose M Faith" A 7 6 Keith Richards "Eileen" A 9 7 L n rd Sk n rd "Good Lovin's ..." 3 8 Spin Doctors Pdnces" A 11 9 Pearl Jam "Black" A 12 10 I, Stradlin "Somebod " • 65 59 Bash & Pop "Loose Ends" A 14 11 Us! Kid Joe "Cats In The..." A 61 60 Dada "Dim" A 17 12 Brian Ma "Driven B You" A 62 61 Blind Melon "Tones Of Home" A 15 13 Drivin-N-Cr in "Turn It Us Or . -

Judas Priest Corregida

EL NOMBRE 1975 1980 British Steel 1984 1992 2008 Toda Europa los ve pasar con su primera El mánager Bill Kurbishley y Allom otra vez Halford anuncia su debut en solitario con Aparece el disco experimental Uno de los integrantes, revisando sus discos, gran gira. Inglaterra será el sitio de como productor dan lugar al Defenders Fight. Luego de tres meses se lleva Nostradamus. se topa con uno de Bob Dylan llamado John partida y llegada: Lateld (Man Hall, el of the Faith de la formación Halford, consigo a Travis. Lo acompañan también 2008 Nostradamus Wesley Harding, el cual contiene el tema 21 de febrero) y Coventri Tech (el 12 de Tipton, Downing, Hill y Holland. Brian Tilse y Russ Parish a las guitarras, y "The Ballad of Frankie Lee and Judas Priest", diciembre). Brillan temas como “Freewheel Burning”, Jay Jay al bajo. por lo que propuso el nombre Judas Priest; Hinch deja los tambores luego de una “Jawbreaker”, “The Sentinel”, “Some así surgió el nombre de la banda. presentación memorable en el Reading Heads Are Gonna Roll” o “Rock Hard Ride En noviembre, el “Metal God” sustituye, Festival. Alan Skip Moore regresa a la Free”, este último es un remake del sin abandonar su nuevo proyecto, a banda y vuelven a componer junto a setentero “Fight for your Life”. Ronnie James Dio en Black Sabbath. Priest. Quienes aún permanecían en Judas 1985 1999 En diciembre los estudios London’s (K. K., Glen e Ian) anuncian su separación. Priest... Live Rob Halford se declara homosexual en Morgan reciben al cuarteto para la televisión y de eso surge la banda Two.