Gender Roles, Family Models and Community-Building Processes in Poblenou Comparative Analysis of American, British and Catalan Soap Operas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Edición Impresa

Larevista Páginas 14 a 19 «SOY UN ROMÁNTICO Follonero Peter Inicia en Cuba Handke EMPEDERNIDO» la tercera Entrevista con Pablo Pineda,que protagoniza temporada Por primera Yo,también junto con Lola Dueñas.Ayer se de ‘Salvados’ vez, su poesía presentó en el Festival de San Sebastián en castellano El precio de la cesta de la compra baja por El primer diario que no se vende primera vez en 21 años Dijous 24 SETEMBRE DEL 2009. ANY IX. NÚMERO 2225 Llenar el carro cuesta ahora un 3,6% menos que el año pasado. Canarias y PaísVasco son las comunidades más caras; y Murcia y Galicia, las más baratas. En Barcelona La Mercè comença amb un pregó que exalta «la gent de mal viure» del Raval podemos ahorrar hasta 1.851 euros al año dependiendo del establecimiento. 2 Montse Carulla i Vicky Peña defensen la «immigra- ció». Arrenquen més de 600 activitats al carrer. 3y17 La reforma del Palau de la Música costó la mitad de lo que decían las cuentas Se habrían puesto de más 12 millones de euros. 2 El TSJ de Castilla y León reconoce la objeción a Educación para la Ciudadanía El tribunal castellano lo admite en dos casos. El Supre- mo falló hace 8 meses a favor de cursar la materia. 6 La UE y EE UU anuncian medidas concretas de OSWALDO RIVAS / REUTERS control para los bancos Primeras víctimas en los disturbios de Honduras Obama elegirá a un supervisor y la Comisión Eu- Una persona murió por un disparo de la Policía, según reconocieron fuentes oficiales, aunque la oposición asegura que ha ha- ropea creará un consejo que vigilará la estabi- bido otras tres víctimas, entre ellas un niño de 8 años, intoxicadas por los gases lacrimógenos. -

The Construction of Gender Roles and Sexual Dissidence on TV

The Construction of Gender Roles And Sexual Dissidence on TV Using Anglo-Saxon Paradigms to Re-read Catalan and Spanish Texts Ph.D. 2013 SILVIA GRASSI Cardiff University 1 Contents Abstract i Acknowledgements ii Introduction 1-20 Chapter 1: The Construction of Gender Roles in Soap Operas: Using Anglo-Saxon Paradigms to Re-read Catalan Texts 21-123 1.1 A Call to Action: Television as a Site for Feminist Struggle 22-33 1.2 How and Why Women Watch Television: From Content Analysis to Audience Analysis 33-42 1.3 Soap Opera: A ‘Female’ Genre? 43-51 1.4 How and Why Women Watch Soap Operas: An Analysis of this Genre’s Appeal for an Audience Constructed as Female 51-67 1.5 Are Soaps all the Same? An Analysis of National Differences within the Genre 68-80 1.6 Are Soaps a Safe Place? An Analysis of Models of Family and the Construction of a Sense of Community in Soaps 80-99 1.7 Learning From Soaps: An Analysis of Soap Operas’ Didactic Aspirations 99-120 1.8 Conclusions 120-123 Chapter 2 The Construction of Sexual Dissidence on TV Using Anglo-Saxon Paradigms to Re-read Spanish and Catalan Texts 124-223 2.1 Do Words Count? A Terminological Clarification 126-131 2 2.2 An Overview of Studies of Non-Heteronormative Content on TV 131-135 2.3 Why Television Counts: The Importance of Non-Heteronormative Media Images 135-141 2.4 Normalisation: Who Has the Right to Belong to a Normal Country? 141-163 2.5 Television’s Construction of Sexual Dissidence: The Dominant Paradigm of Essentialism 163-198 2.6 Constructing a Collective History 198-211 2.7 Television’s Depiction of the Role of the School System in Sustaining Heteronormativity 211-218 2.8 Conclusions 219-223 Conclusion 224-232 Appendix 1 233-273 Appendix 2 274-296 Bibliography 297-331 3 Abstract Taking as a starting point an interpretation of the television medium as an Ideological State Apparatus, in my thesis I examine how gender roles and sexual dissidence are constructed in Spanish and Catalan television series. -

The Sala Beckett's 8Th Obrador D'estiu: from 6 to 13 July 2013

The Sala Beckett's 8th Obrador d'estiu: From 6 to 13 July 2013 An international meeting point for new playwriting This year... with all the rage Contents Welcome p.3 Agenda p.4 Courses and Workshops p.6 Seminar New Plays for a Time of Rage p.12 Open Activities p.20 New Plays for a Time of Rage. Staged readings p.20 Work in progress p.20 Other Activities p.21 Desig Jam p.22 The Obrador d’estiu on Núvol p.23 The Sala Beckett’s Obrador d’estiu Team p.24 Collaborators p.25 2 Welcome! It has now been eight years since the Sala Beckett/Obrador Internacional de Dramatúrgia started organising the Obrador d’estiu, an international meeting of emerging playwrights from around the world. Since 2006, initially in Argelaguer and more recently at different venues around Barcelona, in the month of July, we have been offering an intensive programme lasting a week and made up of courses, seminars, staged readings and other activities linked to contemporary playwriting, directed by some of the most important playwrights or theatre teachers of the moment. This year will see the participation of such professionals as David Harrower, Simon Stephens, Andrés Lima, José Sanchis Sinisterra, Guillem Cluaand Jordi Oriol. In the last two editions, fear and desire respectively were the themes chosen as a motif for the creation of works entrusted to authors hailing from different countries around the world. Thisl year our proposal is rage, not just as a motif for inspiration but also as a creative state of mind that is comprehensible and justifiable, as an attitude of personal and collective confrontation with respect to the economic, social and cultural situation we are currently experiencing. -

Variació Autodiatòpica I Variació Alterdiatòpica En Les Sèries De Televisió En Català

Núm. 8 Coneixements, usos i representacions socials de la llengua catalana 2014 Variació autodiatòpica i variació alterdiatòpica en les sèries de televisió en català David Paloma Mònica Montserrat Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona Universitat Oberta de Catalunya Resum L’article aborda dos conceptes nous del col·loquial mediatitzat en el marc de les sèries de televisió de producció pròpia: variació autodiatòpica i variació alterdiatòpica. Aquesta variació està al servei de la versemblança audiovisual, que és justament el propòsit més destacat del registre col·loquial en el marc de la ficció. L’article pren en consideració un corpus format per 96 capítols d’un total de 24 sèries de producció pròpia de TV3, d’IB3 i de Canal 9, emeses durant els anys 1992-2013, i presenta les principals tendències en la variació diatòpica dels actors i de les actrius en relació amb els personatges que interpreten. Paraules clau: televisió, sèries, variació geogràfica, variació autodiatòpica, varia- ció alterdiatòpica Abstract This article deals with the two new concepts of the mediated colloquial register in relation to the nationally-produced television series: autodiatopic variation and alterdiatopic variation. This kind of variation is at the service of audiovisual credibility, which is precisely the highlighted purpose of the mediated colloquial register within fiction. This article takes into consideration a corpus formed by 96 episodes from a total of 24 national television series produced by TV3, IB3 and Canal 9, which have been emitted from 1992 to 2003, and presents the main trends in the diatopic variation of actors and actresses in relation to their roles. Keywords: television, series, geographical variation, autodiatopic variation, alter- diatopic variation 37 David Paloma,Mònica Montserrat 1. -

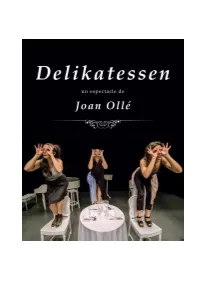

Dossier Premsa Delikatessen-Joan Ollé

Delikatessen, un espectacle de Joan Ollé sobre textos de: Ferran Aixalà, Roland Barthes, Iban Beltran, Stefano Benni, Julio Camba, Marta Carnicero, Narcís Comadira, Vicent Andrés Estellés, David Guzmán, Miquel Martí i Pol, Herman Melville, Joan Ollé, Josep Pla, Jacques Prévert, Marcel Proust, Mestre Robert, Pierre Ronsard, Brillat Savarin, Roland Topor, Miguel de Unamuno, Manuel Vázquez Montalbán, Manuel Vicent, Leonardo da Vinci, i autors anònims. Actors i actrius: Ferran Aixalà Eduard Muntada Clara Olmo Sandra Pujol Marta Rosell Moviment i coreografia: Marta Casals Vestuari: Joan Ros Assessorament hostaleria : Montse Sainz de la Maza Caracterització: Sara Baró Escenografia : Joan Ollé / Joan Pena Attrezzo: Maria Cucurull / Joan Pena Il∙luminació: Micki Arbizu / Alex Roselló Disseny gràfic: Iolanda Monsó Alumne de l’Aula de Teatre en pràctiques: Frank Farré Ajudant de direcció: Isaac Baró Producció: La Remoreu Teatre Agraïments: Íntims produccions, Centre de Titelles de Lleida, Aula de Teatre de Lleida, Teatre de l‟Escorxador, Restaurant Galindo, Restaurant L‟estel de la Mercè, Cafè de l‟ordre del Temple, Sonaktrona, V Tècnics, Antoni Llevot, Margarida Troguet, Hono Martín, Ares Piqué, JoseBergés, Diana Jaureguibehere... Sopa de lletres L‟any 2013 Salvador Sunyer, director de Temporada Alta, em va proposar inaugurar el seu festival amb un espectacle sobre gastronomia. Per què? Perquè els germans Roca I el seu Celler, bons amics de la casa, eren oficialment els millors restauradors del món i, vint anys abans, quan va néixer TA, el Talleret de Salt, hi havia representat un espectacle sobre el menjar I el beure anomenat „Degustació‟. Sembla que tot lligava. El nostre espectacle, que no tenia resen comú amb el seu antecessor, es va representar un sol dia, la nit del 3 d‟octubre, al Teatre Municipal, I allà hi era el més florit de la literatura, el teatre i la cuina catalana. -

Cristina Clemente Sala Tallers

Vimbodí vs. Praga Cristina Clemente Sala Tallers Projecte T6 5a edició 2009/2011: 6 autors 6 textos 6 estrenes Una aposta generacional En aquesta cinquena edició, el TNC ha volgut donar un caràcter específicament generacional al seu programa de promoció de l’escriptura teatral contemporània i, en col·laboració amb la SGAE, ha dissenyat un T6 marcadament jove, especialment cohesionat i amb unes fórmules de treball i producció força noves, que recomanen la reducció a només dos anys de durada del Projecte i a l’estrena d’un sol text per autor a la Sala Tallers del TNC. Els sis autors seleccionats per aquesta nova edició configuren un grup compacte i homogeni ja d’entrada, tant pel que fa a la seva edat (tots ells entorn dels 30 anys), com pel que fa a la seva manera de concebre la creació teatral. Són autors que escriuen des de l’escena més que des de l’escriptori, que consideren el treball amb els actors com una peça fonamental del seu procés creatiu, que es preocupen per connectar al màxim amb els gustos i sensibilitats dels espectadors, que trepitgen gèneres i llenguatges diferents sense prejudicis, i que han après a compartir entre ells els seus dubtes i les seves inquietuds, de manera desacomplexada, a través dels mitjans de comunicació propis d’ara (Internet, Facebook, etc.); una generació teatral nova, que trenca amb l’aïllament de l’autor del text respecte de l’espectacle i a la qual ja s’ha reconegut talent, personalitat, capacitat de comunicació i energia creativa. Es tracta dels sis joves dramaturgs: Marta Buchaca, Jordi Casanovas, Cristina Clemente, Carles Mallol, Josep Maria Miró i Pere Riera. -

Mariona Ribas

CUÍDATELa revista de magazine nº 8 - octubre 2016 salud enfermedades cardiovasculares facial sérums Mariona Ribas "Me gustan los retos" 12 acciones en un producto seborregulador ∙ matificante ∙ reduce los poros dilatados ∙ afinador del relieve ∙ queratolítico · bacteriostático · despigmentante · regenerante · antiageing · calmante · hidratante · antioxidante eficacia comprobada hasta un 93% de reducción de las imperfecciones cutáneas* *Estudio clínico realizado en un laboratorio externo con 20 personas en edades comprendidas entre 18 y 45 años con piel grasa o con tendencia acnéica y con presencia de comedones (granos) tras 29 días de uso (2 veces al día). editorial Es tiempo de OTOÑO Llega la calma y el silencio a nuestras vidas. Los días se acortan y los La revista de paisajes se tiñen de cálidos colores. CUÍDATEmagazine nº 8 - octubre 2016 Apetece acurrucarse en el sofá y disfrutar del sosiego. Es tiempo de preparar mente y cuerpo, de retomar aquello que dejamos pendiente, de cuidar nuestra alimentación salud enfermedades y de empaparnos de las nuevas cardiovasculares tendencias. Es tiempo de CUÍDATE. facial sérums El número de octubre lo protagonizan Mariona dos mujeres ‘exclusivas’: la actriz, Ribas Mariona Ribas que acaba de "Me gustan incorporarse a la 5ª temporada de los retos" la serie “Amar es para siempre” y la periodista y presentadora Ainhoa Arbizu que vive el momento más EN PORTADA importante de su vida, la llegada de Mariona su primer hijo. Ambas han querido compartir con nosotros su presente. Ribas Un mes más, te invitamos a descubrir «Me gustan los retos» el Universo CUÍDATE: salud, belleza, autocuidado y estilo de vida para ti y los que más quieres. -

Isaac Morera I Socias Barcelona, 16 De Juliol 1975 [email protected]

Isaac Morera i Socias Barcelona, 16 de Juliol 1975 [email protected] www.isaacmorera.com Actor 2005-2006 Les Aventures Extraordinàries d’en Massagran Teatre Nacional de Catalunya. Barcelona. Dir. Joan Castells Producció del TNC a partir del llibre del mateix títol d’en R. Folch i Torres. 2005-2006 En què pensa, Professor Einstein? Auditori del Cosmocaixa. Barcelona. Dir. Mireia Chalamanc Espectacle que acosta a l’espectador la figura del científic Albert Einstein, en el centenari de les teories que van canviar la història de la Física. 2005-.... Rondalles al Sac Lo Sacaire del Llobregat. El Prat de Llobregat. Producció pròpia Estreno al Prat de Llobregat a la Diada de Sant Jordi. Espectacle de carrer que consisteix en un cercavila amb sac de gemecs. L’objectiu del qual és atreure la gent cap a on explico una rondalla dramatitzada. 2004-.... Animacions a la Lectura Editorial Alfaguara. Barcelona. Dir. Artur Font Entro en aquesta Editorial com a actor-animador. Ressegueixo totes les Escoles de Catalunya explicant rondalles dramatitzades i jocs literaris relacionats amb les lectures que n’han fet els alumnes. 2004 GAYS punto COM (Sèrie TV) Estudios Gala. Barcelona. Dir. Esther Cámara Representant el personatge de “Oscar”, co-protagonitzo aquesta sèrie de TV. Gravo 13 capítols. 2004 Playing Richard Cia. Le Fly. El Prat de Llobregat. Dir. Ivan Tapia Espectacle a partir de la nova traducció al català d’en Salvador Oliva, de la peça teatral de W. Shakespeare, Richard III. 2003 Potiner (Videoclip) Cheb Balowsky 2002 Spain Cia. Contratac. Terrassa. Dir. R. Jordan i X. Calderer Cia. d’esgrima teatral. -

Communication & Society Comunicación Y Sociedad

COMMUNICATION & SOCIETY COMUNICACIÓN Y SOCIEDAD © 2013 Communication&Society/Comunicación y Sociedad ISSN 0214‐0039 E ISSN 2174-0895 www.unav.es/fcom/comunicacionysociedad/en/ www.comunicacionysociedad.com COMMUNICATION&SOCIETY/ COMUNICACIÓN Y SOCIEDAD Vol. XXVI • N.3 • 2013 • pp. 67‐97 How to cite this article: TOUS-ROVIROSA, A., MESO AYERDI, K., SIMELIO SOLA, N., “The Representation of Women’s Roles in Television Series in Spain. Analysis of the Basque and Catalan Cases”, Communication&Society/Comunicación y Sociedad, Vol. 26, n. 3, 2013, pp. 67-97. The Representation of Women’s Roles in Television Series in Spain. Analysis of the Basque and Catalan Cases La imagen de la mujer en series de televisión españolas. Análisis de los casos Vasco y Catalán ANNA TOUS-ROVIROSA, KOLDO MESO AYERDI, NURIA SIMELIO SOLA. [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Anna Tous-Rovirosa. Autonomous University of Barcelona (UAB). Faculty of Communication Sciences. Journalism and Communication Sciences Department. 08193 Bellaterra (Spain). Koldo Meso Ayerdi. Basque Country University. Faculty of Social Sciences and Communication. Journalism II Department. 48940m Leioa (Spain). Nuria Simelio Sola. Autonomous University of Barcelona (UAB). Journalism and Communication Sciences Department. 08193 Bellaterra (Spain). Submitted: April 11, 2013 Approved: May 4, 2013 ABSTRACT: The comparison of six Spanish television dramas has enabled us to analyse the role of women in these fictional products. In the series analysed there is a persistence of males playing the leading roles, as well as a reiteration of female stereotypes. In the case of the Catalan television dramas on TVC (El cor de la ciutat, Ventdelplà and Infidels) a more positive treatment of femininity could be observed in the series dealing with social customs. -

La Casa De Bernarda Alba 1

Magatzem d’Ars presenta: LA CASA DE BERNARDA ALBA 1 ÍNDICE El espectáculo……………………………………………………………………………….………………….2 Nota del director…………………………………………………………………………….………………..3 Ficha artística…………………………………………………………………………………………………..4 La compañía…………………………………………………………………………………………………….5 CV actrices………………………………...................…………………………………………………………..6 Algunas opiniones del espectáculo……………………………………………………………………9 Comunicación del espectáculo……………….………………………………………………………….10 Contacto…………………………...………………………………………………………………………………11 LA CASA DE BERNARDA ALBA 2 EL ESPECTÁCULO Adaptación libre con 6 actrices y una duración de 60 minutos aproximadamente. A la muerte de su marido, Bernarda impone a sus hijas un luto riguroso de ocho años. Tan riguroso que ni siquiera podrán salir de casa, frustrando así las necesidades de sus tres hijas, “en edad de merecer”. Después de haber negado a Martirio como prometida a un Humanes “por ser gañan, compromete a Angustias con Pepe el Romano. La aparición de este personaje desencadena una serie de acontecimientos que degenera en una confrontación entre la madre y las hijas. Poncia una de las criadas de confianza de la casa, trata de advertir a la señora sobre las consecuencias de una disciplina tan rígida. Pero Bernarda rechaza todas las críticas; primero para no perder su aparente seguridad y, segundo, porque no puede aceptar consejos de una persona que está a su servicio. LA CASA DE BERNARDA ALBA 3 NOTA DEL DIRECTOR Los ensayos de esta obra, han estado realizados recreando en primer lugar y como premisa importante las sensaciones que produce el espacio en las actrices: La sensación de calor por las altas temperaturas que a veces se entre mezcla con el calor del deseo sexual, la sensación de estar en una prisión encerradas y sin contacto con el exterior, la ansiedad que se produce entre las hermanas, el miedo a su madre (Bernarda), el odio hacia los hombres y la lucha entre hermanas por conseguir al único hombre que tiene un papel protagonista en el espectáculo sin aparecer en él. -

Sábado,6Demayode2006

MUNDO DEPORTIVO Sábado, 6 de mayo de 2006 PROGRAMACION 53 ELABORACIÓN: INFOCABLE EDITORIAL, SL. (www.infocable.biz) > TVE 1 La 2 Tele 5Antena 3 TV TV3 K3/33 Cuatro Td8 6.00 Canal 24 horas (noticias). 6.00 That's English (educativo). 6.30 UFO Baby (serie). (ST) 8.00 Megatrix (infantil). 6.00 Notícies 3/24. 7.00 Travessies en camió. 8.00 Cuatrosfera (magazine 7.35 Molt animats. 8.00 Hora Warner. Incluye: 7.30 UNED (educativo). 7.00 El príncipe Mackaroo. Presentadores: Jordi Cruz y 8.00 Club Super3. Incluye: 'Els (Nuevo en emisión.) juvenil). Incluye: 'Mundo 12.20 Pel·lícula: 'Amarga 'Duck Dodgers', 'Looney 8.00 Los conciertos de La 2. (E) (serie): 'Jugando a la oca en Natalia. Incluye los investigadors dels contes' 7.55 Terres, homes, aventures. salvaje'; 'V'; 'Rebelde Way', victoria'. (R) Tunes' y 'Batman'. (ST) (E) 9.30 Agrosfera (agronomía). un día de lluvia'. (ST) siguientes espacios: 'Yugi (8.05), 'Rovelló' (8.30) (ST), 8.40 Patagònia terra del sud. '40 Pop'; 'Surferos TV', y 14.00 Pel·lícula: 'Pequeños 9.05 Zon@Disney. Incluye: 10.30 En otras palabras. 7.15 El mundo mágico de GX', 'Bob Esponja', 'Jimmy 'Spirou' (9.00), 'Corrector (ST) 'Tan muertos como yo'. desordenes amorosos'. (R) Mañana 'House of mouse', 'Lilo & 11.00 Parlamento (informativo). Brunelesky (infantil). Neutrón', 'Art Attack', Yui' (9.25) (ST), 'Kiteretsu, 9.05 Agenda accents. 13.57 Noticias Cuatro. 15.30 Primera sessió: 'Tranvía a Stich', 'American Dragon' y 12.00 El conciertazo. (E) 7.30 Birlokus klub (infantil). 'Lizzie Maguire', 'Malcolm el cosí més llest d'en 9.15 Nydia. -

Pedro Almodóvar JULIETA (2016), 99 Min

November 27, 2017 (XXXV:14) Pedro Almodóvar JULIETA (2016), 99 min. (The online version of this handout has color images and hot urls.) Directed by Pedro Almodóvar Written by Pedro Almodóvar (screenplay) Alice Munro (based on the short stories "Destino", "Pronto" and "Silencio") Produced by Agustín Almodóvar, Diego Pajuelo, Bárbara Peiró ... associate producer Music Alberto Iglesias Cinematography Jean-Claude Larrieu Film Editing José Salcedo Art Direction Carlos Bodelón Cast Emma Suárez…Julieta Adriana Ugarte…Julieta Joven it. Instead, Almodóvar bought a Super 8 camera and began to Daniel Grao…Xoan shoot short films on his own. “I had no budget, no money,” he Inma Cuesta…Ava says. “The important thing was to make movies.” He wrote out Darío Grandinetti…Lorenzo complete scripts, even though his camera couldn’t record sound, Michelle Jenner…Beatriz and changed the characters depending on which of his friends Pilar Castro…Claudia showed up for a shoot. He avoided filming where he might bump Nathalie Poza…Juana into the authorities, and so he made several Biblical epics in the Susi Sánchez...Sara countryside, giving them, he says, “a bucolic and abstract air, the Joaquín Notario…Samuel opposite of Cecil B. De Mille’s.” Since he had no money to buy Priscilla Delgado…Antía (Adolescente) lights, many of the scenes in his Super 8 movies were filmed on Blanca Parés…Antía (18 años) rooftops, in parks, and by windows. “Fortunately, Spain is a Rossy de Palma…Marian place with a lot of natural light.” The director’s first Super 8 movies are too damaged to be shown today.