Conversion of D-Ribulose 5-Phosphate to D-Xylulose 5-Phosphate: New Insights from Structural and Biochemical Studies on Human RPE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lecture 7 - the Calvin Cycle and the Pentose Phosphate Pathway

Lecture 7 - The Calvin Cycle and the Pentose Phosphate Pathway Chem 454: Regulatory Mechanisms in Biochemistry University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire 1 Introduction The Calvin cycle Text The dark reactions of photosynthesis in green plants Reduces carbon from CO2 to hexose (C6H12O6) Requires ATP for free energy and NADPH as a reducing agent. 2 2 Introduction NADH versus Text NADPH 3 3 Introduction The Pentose Phosphate Pathway Used in all organisms Glucose is oxidized and decarboxylated to produce reduced NADPH Used for the synthesis and degradation of pentoses Shares reactions with the Calvin cycle 4 4 1. The Calvin Cycle Source of carbon is CO2 Text Takes place in the stroma of the chloroplasts Comprises three stages Fixation of CO2 by ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate to form two 3-phosphoglycerate molecules Reduction of 3-phosphoglycerate to produce hexose sugars Regeneration of ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate 5 5 1. Calvin Cycle Three stages 6 6 1.1 Stage I: Fixation Incorporation of CO2 into 3-phosphoglycerate 7 7 1.1 Stage I: Fixation Rubisco: Ribulose 1,5- bisphosphate carboxylase/ oxygenase 8 8 1.1 Stage I: Fixation Active site contains a divalent metal ion 9 9 1.2 Rubisco Oxygenase Activity Rubisco also catalyzes a wasteful oxygenase reaction: 10 10 1.3 State II: Formation of Hexoses Reactions similar to those of gluconeogenesis But they take place in the chloroplasts And use NADPH instead of NADH 11 11 1.3 State III: Regeneration of Ribulose 1,5-Bisphosphosphate Involves a sequence of transketolase and aldolase reactions. 12 12 1.3 State III: -

Carbohydrates: Structure and Function

CARBOHYDRATES: STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION Color index: . Very important . Extra Information. “ STOP SAYING I WISH, START SAYING I WILL” 435 Biochemistry Team *هذا العمل ﻻ يغني عن المصدر المذاكرة الرئيسي • The structure of carbohydrates of physiological significance. • The main role of carbohydrates in providing and storing of energy. • The structure and function of glycosaminoglycans. OBJECTIVES: 435 Biochemistry Team extra information that might help you 1-synovial fluid: - It is a viscous, non-Newtonian fluid found in the cavities of synovial joints. - the principal role of synovial fluid is to reduce friction between the articular cartilage of synovial joints during movement O 2- aldehyde = terminal carbonyl group (RCHO) R H 3- ketone = carbonyl group within (inside) the compound (RCOR’) 435 Biochemistry Team the most abundant organic molecules in nature (CH2O)n Carbohydrates Formula *hydrate of carbon* Function 1-provides important part of energy Diseases caused by disorders of in diet . 2-Acts as the storage form of energy carbohydrate metabolism in the body 3-structural component of cell membrane. 1-Diabetesmellitus. 2-Galactosemia. 3-Glycogen storage disease. 4-Lactoseintolerance. 435 Biochemistry Team Classification of carbohydrates monosaccharides disaccharides oligosaccharides polysaccharides simple sugar Two monosaccharides 3-10 sugar units units more than 10 sugar units Joining of 2 monosaccharides No. of carbon atoms Type of carbonyl by O-glycosidic bond: they contain group they contain - Maltose (α-1, 4)= glucose + glucose -Sucrose (α-1,2)= glucose + fructose - Lactose (β-1,4)= glucose+ galactose Homopolysaccharides Heteropolysaccharides Ketone or aldehyde Homo= same type of sugars Hetero= different types Ketose aldose of sugars branched unBranched -Example: - Contains: - Contains: Examples: aldehyde group glycosaminoglycans ketone group. -

PENTOSE PHOSPHATE PATHWAY — Restricted for Students Enrolled in MCB102, UC Berkeley, Spring 2008 ONLY

Metabolism Lecture 5 — PENTOSE PHOSPHATE PATHWAY — Restricted for students enrolled in MCB102, UC Berkeley, Spring 2008 ONLY Bryan Krantz: University of California, Berkeley MCB 102, Spring 2008, Metabolism Lecture 5 Reading: Ch. 14 of Principles of Biochemistry, “Glycolysis, Gluconeogenesis, & Pentose Phosphate Pathway.” PENTOSE PHOSPHATE PATHWAY This pathway produces ribose from glucose, and it also generates 2 NADPH. Two Phases: [1] Oxidative Phase & [2] Non-oxidative Phase + + Glucose 6-Phosphate + 2 NADP + H2O Ribose 5-Phosphate + 2 NADPH + CO2 + 2H ● What are pentoses? Why do we need them? ◦ DNA & RNA ◦ Cofactors in enzymes ● Where do we get them? Diet and from glucose (and other sugars) via the Pentose Phosphate Pathway. ● Is the Pentose Phosphate Pathway just about making ribose sugars from glucose? (1) Important for biosynthetic pathways using NADPH, and (2) a high cytosolic reducing potential from NADPH is sometimes required to advert oxidative damage by radicals, e.g., ● - ● O2 and H—O Metabolism Lecture 5 — PENTOSE PHOSPHATE PATHWAY — Restricted for students enrolled in MCB102, UC Berkeley, Spring 2008 ONLY Two Phases of the Pentose Pathway Metabolism Lecture 5 — PENTOSE PHOSPHATE PATHWAY — Restricted for students enrolled in MCB102, UC Berkeley, Spring 2008 ONLY NADPH vs. NADH Metabolism Lecture 5 — PENTOSE PHOSPHATE PATHWAY — Restricted for students enrolled in MCB102, UC Berkeley, Spring 2008 ONLY Oxidative Phase: Glucose-6-P Ribose-5-P Glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase. First enzymatic step in oxidative phase, converting NADP+ to NADPH. Glucose 6-phosphate + NADP+ 6-Phosphoglucono-δ-lactone + NADPH + H+ Mechanism. Oxidation reaction of C1 position. Hydride transfer to the NADP+, forming a lactone, which is an intra-molecular ester. -

Ii- Carbohydrates of Biological Importance

Carbohydrates of Biological Importance 9 II- CARBOHYDRATES OF BIOLOGICAL IMPORTANCE ILOs: By the end of the course, the student should be able to: 1. Define carbohydrates and list their classification. 2. Recognize the structure and functions of monosaccharides. 3. Identify the various chemical and physical properties that distinguish monosaccharides. 4. List the important monosaccharides and their derivatives and point out their importance. 5. List the important disaccharides, recognize their structure and mention their importance. 6. Define glycosides and mention biologically important examples. 7. State examples of homopolysaccharides and describe their structure and functions. 8. Classify glycosaminoglycans, mention their constituents and their biological importance. 9. Define proteoglycans and point out their functions. 10. Differentiate between glycoproteins and proteoglycans. CONTENTS: I. Chemical Nature of Carbohydrates II. Biomedical importance of Carbohydrates III. Monosaccharides - Classification - Forms of Isomerism of monosaccharides. - Importance of monosaccharides. - Monosaccharides derivatives. IV. Disaccharides - Reducing disaccharides. - Non- Reducing disaccharides V. Oligosaccarides. VI. Polysaccarides - Homopolysaccharides - Heteropolysaccharides - Carbohydrates of Biological Importance 10 CARBOHYDRATES OF BIOLOGICAL IMPORTANCE Chemical Nature of Carbohydrates Carbohydrates are polyhydroxyalcohols with an aldehyde or keto group. They are represented with general formulae Cn(H2O)n and hence called hydrates of carbons. -

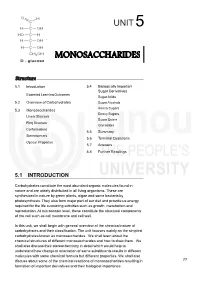

Monosaccharides

UNIT 5 MONOSACCHARIDES Structure 5.1 Introduction 5.4 Biologically Important Sugar Derivatives Expected Learning Outcomes Sugar Acids 5.2 Overview of Carbohydrates Sugar Alcohols Amino Sugars 5.3 Monosaccharides Deoxy Sugars Linear Structure Sugar Esters Ring Structure Glycosides Conformations 5.5 Summary Stereoisomers 5.6 Terminal Questions Optical Properties 5.7 Answers 5.8 Further Readings 5.1 INTRODUCTION Carbohydrates constitute the most abundant organic molecules found in nature and are widely distributed in all living organisms. These are synthesized in nature by green plants, algae and some bacteria by photosynthesis. They also form major part of our diet and provide us energy required for the life sustaining activities such as growth, metabolism and reproduction. At microscopic level, these constitute the structural components of the cell such as cell membrane and cell wall. In this unit, we shall begin with general overview of the chemical nature of carbohydrates and their classification. The unit focuses mainly on the simplest carbohydrates known as monosaccharides. We shall learn about the chemical structures of different monosaccharides and how to draw them. We shall also discuss their stereochemistry in detail which would help to understand how change in orientation of same substituents results in different molecules with same chemical formula but different properties. We shall also discuss about some of the chemical reactions of monosaccharides resulting in 77 formation of important derivatives and their biological importance. -

Production of Prebiotic Exopolysaccharides by Lactobacilli

Lehrstuhl für Technische Mikrobiologie Production of prebiotic exopolysaccharides by lactobacilli Markus Tieking Vollständiger Abdruck der von der Fakultät Wissenschaftszentrum Weihenstephan für Ernährung, Landnutzung und Umwelt der Technischen Universität München zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Doktor - Ingenieurs genehmigten Dissertation. Vorsitzender: Univ.-Prof. Dr.- Ing. E. Geiger Prüfer der Dissertation: 1. Univ.-Prof. Dr. rer. nat. habil. R. F. Vogel 2. Univ.-Prof. Dr.- Ing. D. Weuster-Botz Die Dissertation wurde am 09.03.2005 bei der Technischen Universität eingereicht und durch die Fakultät Wissenschaftszentrum Weihenstephan für Ernährung, Landnutzung und Umwelt am 27.05.2005 angenommen. Lehrstuhl für Technische Mikrobiologie Production of prebiotic exopolysaccharides by lactobacilli Markus Tieking Doctoral thesis Fakultät Wissenschaftszentrum Weihenstephan für Ernährung, Landnutzung und Umwelt Freising 2005 Mein Dank gilt meinem Doktorvater Prof. Rudi Vogel für die Überlassung des Themas sowie die stete Diskussionsbereitschaft, Dr. Michael Gänzle für die kritische Begleitung, die ständige Diskussionsbereitschaft sowie sein fachliches Engagement, welches weit über das übliche Maß hinaus geht, Dr. Matthias Ehrmann für seine uneingeschränkte Bereitwilligkeit, sein Wissen auf dem Gebiet der Molekularbiologie weiterzugeben, seine unschätzbar wertvollen praktischen Ratschläge auf diesem Gebiet sowie für seine Geduld, meiner lieben Frau Manuela, deren Motivationskünste und emotionale Unterstützung mir wissenschaftliche -

Production of Natural and Rare Pentoses Using Microorganisms and Their Enzymes

EJB Electronic Journal of Biotechnology ISSN: 0717-3458 Vol.4 No.2, Issue of August 15, 2001 © 2001 by Universidad Católica de Valparaíso -- Chile Received April 24, 2001 / Accepted July 17, 2001 REVIEW ARTICLE Production of natural and rare pentoses using microorganisms and their enzymes Zakaria Ahmed Food Science and Biochemistry Division Faculty of Agriculture, Kagawa University Kagawa 761-0795, Kagawa-Ken, Japan E-mail: [email protected] Financial support: Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture of Japan under scholarship program for foreign students. Keywords: enzyme, microorganism, monosaccharides, pentose, rare sugar. Present address: Scientific Officer, Microbiology and Biochemistry Division, Bangladesh Jute Research Institute, Shere-Bangla Nagar, Dhaka- 1207, Bangladesh. Tel: 880-2-8124920. Biochemical methods, usually microbial or enzymatic, murine tumors and making them useful for cancer treatment are suitable for the production of unnatural or rare (Morita et al. 1996; Takagi et al. 1996). Recently, monosaccharides. D-Arabitol was produced from D- researchers have found many important applications of L- glucose by fermentation with Candida famata R28. D- arabinose in medicine as well as in biological sciences. In a xylulose can also be produced from D-arabitol using recent investigation, Seri et al. (1996) reported that L- Acetobacter aceti IFO 3281 and D-lyxose was produced arabinose selectively inhibits intestinal sucrase activity in enzymatically from D-xylulose using L-ribose isomerase an uncompetitive manner and suppresses the glycemic (L-RI). Ribitol was oxidized to L-ribulose by microbial response after sucrose ingestion by such inhibition. bioconversion with Acetobacter aceti IFO 3281; L- Furthermore, Sanai et al. (1997) reported that L-arabinose ribulose was epimerized to L-xylulose by the enzyme D- is useful in preventing postprandial hyperglycemia in tagatose 3-epimerase and L-lyxose was produced by diabetic patients. -

Wo 2008/045259 A2

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (43) International Publication Date PCT (10) International Publication Number 17 April 2008 (17.04.2008) WO 2008/045259 A2 (51) International Patent Classification: (74) Agents: LEVINE, Edward, L. et al; Cargill, Incorpo A23L 1/00 (2006.01) A23L 1/0532 (2006.01) rated, 15407 McGinty Road West, MS 24, Wayzata, M in A23L 1/0524 (2006.01) nesota 55391 (US). (21) International Application Number: (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every PCT/US2007/021245 kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, AT,AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BR, BW, BY, BZ, CA, CH, (22) International Filing Date: 3 October 2007 (03.10.2007) CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, DO, DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, (25) Filing Language: English IN, IS, JP, KE, KG, KM, KN, KP, KR, KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LT, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, OM, PG, PH, PL, (26) Publication Language: English PT, RO, RS, RU, SC, SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, SV, SY, TJ, TM, TN, TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, (30) Priority Data: ZM, ZW 11/544,989 6 October 2006 (06.10.2006) US (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every (71) Applicant (for all designated States except US): kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, CARGILL, INCORPORATED [US/US]; 15407 GM, KE, LS, MW, MZ, NA, SD, SL, SZ, TZ, UG, ZM, McGinty Road West, MS 24, Wayzata, Minnesota ZW), Eurasian (AM, AZ, BY, KG, KZ, MD, RU, TJ, TM), 55391 (US). -

Nucleotide Sugars in Chemistry and Biology

molecules Review Nucleotide Sugars in Chemistry and Biology Satu Mikkola Department of Chemistry, University of Turku, 20014 Turku, Finland; satu.mikkola@utu.fi Academic Editor: David R. W. Hodgson Received: 15 November 2020; Accepted: 4 December 2020; Published: 6 December 2020 Abstract: Nucleotide sugars have essential roles in every living creature. They are the building blocks of the biosynthesis of carbohydrates and their conjugates. They are involved in processes that are targets for drug development, and their analogs are potential inhibitors of these processes. Drug development requires efficient methods for the synthesis of oligosaccharides and nucleotide sugar building blocks as well as of modified structures as potential inhibitors. It requires also understanding the details of biological and chemical processes as well as the reactivity and reactions under different conditions. This article addresses all these issues by giving a broad overview on nucleotide sugars in biological and chemical reactions. As the background for the topic, glycosylation reactions in mammalian and bacterial cells are briefly discussed. In the following sections, structures and biosynthetic routes for nucleotide sugars, as well as the mechanisms of action of nucleotide sugar-utilizing enzymes, are discussed. Chemical topics include the reactivity and chemical synthesis methods. Finally, the enzymatic in vitro synthesis of nucleotide sugars and the utilization of enzyme cascades in the synthesis of nucleotide sugars and oligosaccharides are briefly discussed. Keywords: nucleotide sugar; glycosylation; glycoconjugate; mechanism; reactivity; synthesis; chemoenzymatic synthesis 1. Introduction Nucleotide sugars consist of a monosaccharide and a nucleoside mono- or diphosphate moiety. The term often refers specifically to structures where the nucleotide is attached to the anomeric carbon of the sugar component. -

A Genetically Adaptable Strategy for Ribose Scavenging in a Human Gut Symbiont Plays a 4 Diet-Dependent Role in Colon Colonization 5 6 7 8 Robert W

1 2 3 A genetically adaptable strategy for ribose scavenging in a human gut symbiont plays a 4 diet-dependent role in colon colonization 5 6 7 8 Robert W. P. Glowacki1, Nicholas A. Pudlo1, Yunus Tuncil2,3, Ana S. Luis1, Anton I. Terekhov2, 9 Bruce R. Hamaker2 and Eric C. Martens1,# 10 11 12 13 1Department of Microbiology and Immunology, University of Michigan Medical School, Ann 14 Arbor, MI 48109 15 16 2Department of Food Science and Whistler Center for Carbohydrate Research, Purdue 17 University, West Lafayette, IN 47907 18 19 3Current location: Department of Food Engineering, Ordu University, Ordu, Turkey 20 21 22 23 Correspondence to: [email protected] 24 #Lead contact 25 26 Running Title: Bacteroides ribose utilization 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 Summary 39 40 Efficient nutrient acquisition in the competitive human gut is essential for microbial 41 persistence. While polysaccharides have been well-studied nutrients for the gut microbiome, 42 other resources such as co-factors and nucleic acids have been less examined. We describe a 43 series of ribose utilization systems (RUSs) that are broadly represented in Bacteroidetes and 44 appear to have diversified to allow access to ribose from a variety of substrates. One Bacteroides 45 thetaiotaomicron RUS variant is critical for competitive gut colonization in a diet-specific 46 fashion. Using molecular genetics, we probed the nature of the ribose source underlying this diet- 47 specific phenotype, revealing that hydrolytic functions in RUS (e.g., to cleave ribonucleosides) 48 are present but dispensable. Instead, ribokinases that are activated in vivo and participate in 49 cellular ribose-phosphate metabolism are essential. -

CH 460 Dr. Muccio Worksheet 4 1. What Is the Difference Between An

CH 460 Dr. Muccio Worksheet 4 1. What is the difference between an aldose and a ketose? 2. What is the oxidation number of the carbon on the following 3 groups? 3. Circle the carbons in the figure below that are chiral. How many isomers does this molecule have? 4. What is the difference between an epimer and an enantiomer? 5. How is the Fisher projection of D-glucose converted to L-glucose? 6. The chemical formula of a tetrose monosaccharide is _____. a. C6H12O6 b.C4H10O4 c.C6H10O4 d.C4H8O4 e.None 7. Match the carbohydrates to their descriptions on the left. i. D-Glyceraldehyde _____ A. C-2 Epimer of Glucose ii. D-Threose _____ B. C-2 Epimer of Threose iii. D-Ribose _____ C. Pentose with D,D,D stereochem iv. D-Mannose _____ D. Triose v. D-Galactose _____ E. Hexose with DLDD stereochem vi. D-Erythrose _____ F. C-3 Epimer of Ribose vii. D-Xylose _____ G. C-4 Epimer of Glucose viii. D-Glucose _____ H. C-2 Epimer of Erythrose ix. D-Arabinose _____ I. C-2 Epimer of Ribose x. D-Fructose _____ J. Ketose of Letter D xi. D-Xylulose _____ K. Ketose of Letter F xii. D-Erythrulose _____ L. Enantiomer of Letter A xiii. Dihydroxyacetone ____ M. Ketose of Letter B xiv. D-Ribulose _____ N. Ketose of Letter E xv. L-Mannose _____ O. Ketose of Letter C CH 460 Dr. Muccio Worksheet 4 8. In the conversion of aldoses to their ketoses, the _____ carbon loses its stererochemistry. -

Novel Fructans from Acetic Acid Bacteria

TECHNISCHE UNIVERSITÄT MÜNCHEN Lehrstuhl für Technische Mikrobiologie Novel fructans from acetic acid bacteria Frank Jakob Vollständiger Abdruck der von der Fakultät Wissenschaftszentrum Weihenstephan für Ernährung, Landnutzung und Umwelt der Technischen Universität München zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Doktors der Naturwissenschaften genehmigten Dissertation. Vorsitzender: Univ.-Prof. Dr. S. Scherer Prüfer der Dissertation: 1. Univ.-Prof. Dr. R. F. Vogel 2. Univ.-Prof. Dr. W. Liebl 3. apl. Prof. Dr. P. Köhler Die Dissertation wurde am 23.01.2014 bei der Technischen Universität München eingereicht und durch die Fakultät Wissenschaftszentrum Weihenstephan für Ernährung, Landnutzung und Umwelt am 15.04.2014 angenommen. VORWORT Die vorliegende Arbeit wurde durch Fördermittel des Bundesministeriums für Ernährung, Landwirtschaft und Verbraucherschutz (BMELV) über die Bundesanstalt für Landwirtschaft und Ernährung (BLE) unterstützt (Projekt 28-1-63.001-07). Mein besonderer Dank gilt meinem Doktorvater Prof. Dr. Rudi F. Vogel für die Möglichkeit, diese Dissertation an seinem Institut durchzuführen. Zudem möchte ich mich für seine konstruktiven Anregungen zu dieser Arbeit, sein entgegengebrachtes Vertrauen, seinen ständigen Einsatz für meine Weiterbeschäftigung an seinem Institut und für seine Unterstützung, mich wissenschaftlich weiter entwickeln zu können, bedanken. Mein außerordentlicher Dank gilt ihm außerdem für sein entgegengebrachtes Verständnis in schwierigen Phasen. Bei Dr. Daniel Meißner und Dr. Susanne Kaditzky möchte ich mich für die hilfreiche und angenehme Betreuung und bei Maria Hermann für die gute Zusammenarbeit im Projekt bedanken. Mein besonderer Dank gilt zudem Stefan Steger für die Durchführung von Backversuchen. Bei Dr. Andre Pfaff und Dr. Ramon Novoa-Carballal möchte ich mich für die entspannte Kooperation, die Durchführung von NMR-Messungen und die Bereitstellung von aufgenommenen Spektren bedanken.