Novel Fructans from Acetic Acid Bacteria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Identification of Strains Isolated in Thailand and Assigned to the Genera Kozakia and Swaminathania

JOURNAL OF CULTURE COLLECTIONS Volume 6, 2008-2009, pp. 61-68 IDENTIFICATION OF STRAINS ISOLATED IN THAILAND AND ASSIGNED TO THE GENERA KOZAKIA AND SWAMINATHANIA Jintana Kommanee1, Somboon Tanasupawat1,*, Ancharida Akaracharanya2, Taweesak Malimas3, Pattaraporn Yukphan3, Yuki Muramatsu4, Yasuyoshi Nakagawa4 and Yuzo Yamada3,† 1Department of Microbiology, Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok 10330, Thailand; 2Department of Microbiology, Faculty of Science, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok 10330, Thailand; 3BIOTEC Culture Collection, National Center for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology, Pathumthani 12120, Thailand; 4Biological Resource Center, Department of Biotechnology, National Institute of Technology and Evaluation, Kisarazu 292-0818, Japan; †JICA Senior Overseas Volunteer, Japan International Cooperation Agency, Shibuya-ku, Tokyo 151-8558, Japan; Professor Emeritus, Shizuoka University, Suruga-ku, Shizuoka 422-8529, Japan *Corresponding author, e-mail: [email protected] Summary Four isolates, isolated from fruit of sapodilla collected at Chantaburi and designated as CT8-1 and CT8-2, and isolated from seeds of ixora („khem” in Thai, Ixora species) collected at Rayong and designated as SI15-1 and SI15-2, were examined taxonomically. The four isolates were selected from a total of 181 isolated acetic acid bacteria. Isolates CT8-1 and CT8-2 were non motile and produced a levan-like mucous polysaccharide from sucrose or D-fructose, but did not produce a water-soluble brown pigment from D-glucose on CaCO3-containing agar slants. The isolates produced acetic acid from ethanol and oxidized acetate and lactate to carbon dioxide and water, but the intensity of the acetate and lactate oxidation was weak. Their growth was not inhibited by 0.35 % acetic acid (v/v) at pH 3.5. -

Lecture 7 - the Calvin Cycle and the Pentose Phosphate Pathway

Lecture 7 - The Calvin Cycle and the Pentose Phosphate Pathway Chem 454: Regulatory Mechanisms in Biochemistry University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire 1 Introduction The Calvin cycle Text The dark reactions of photosynthesis in green plants Reduces carbon from CO2 to hexose (C6H12O6) Requires ATP for free energy and NADPH as a reducing agent. 2 2 Introduction NADH versus Text NADPH 3 3 Introduction The Pentose Phosphate Pathway Used in all organisms Glucose is oxidized and decarboxylated to produce reduced NADPH Used for the synthesis and degradation of pentoses Shares reactions with the Calvin cycle 4 4 1. The Calvin Cycle Source of carbon is CO2 Text Takes place in the stroma of the chloroplasts Comprises three stages Fixation of CO2 by ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate to form two 3-phosphoglycerate molecules Reduction of 3-phosphoglycerate to produce hexose sugars Regeneration of ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate 5 5 1. Calvin Cycle Three stages 6 6 1.1 Stage I: Fixation Incorporation of CO2 into 3-phosphoglycerate 7 7 1.1 Stage I: Fixation Rubisco: Ribulose 1,5- bisphosphate carboxylase/ oxygenase 8 8 1.1 Stage I: Fixation Active site contains a divalent metal ion 9 9 1.2 Rubisco Oxygenase Activity Rubisco also catalyzes a wasteful oxygenase reaction: 10 10 1.3 State II: Formation of Hexoses Reactions similar to those of gluconeogenesis But they take place in the chloroplasts And use NADPH instead of NADH 11 11 1.3 State III: Regeneration of Ribulose 1,5-Bisphosphosphate Involves a sequence of transketolase and aldolase reactions. 12 12 1.3 State III: -

Conversion of D-Ribulose 5-Phosphate to D-Xylulose 5-Phosphate: New Insights from Structural and Biochemical Studies on Human RPE

The FASEB Journal • Research Communication Conversion of D-ribulose 5-phosphate to D-xylulose 5-phosphate: new insights from structural and biochemical studies on human RPE Wenguang Liang,*,†,1 Songying Ouyang,*,1 Neil Shaw,* Andrzej Joachimiak,‡ Rongguang Zhang,* and Zhi-Jie Liu*,2 *National Laboratory of Biomacromolecules, Institute of Biophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China; †Graduate University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China; and ‡Structural Biology Center, Argonne National Laboratory, Argonne, Illinois, USA ABSTRACT The pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) such as erythrose 4-phosphate, glyceraldehyde 3-phos- confers protection against oxidative stress by supplying phate, and fructose 6-phosphate that are necessary for NADPH necessary for the regeneration of glutathione, the synthesis of aromatic amino acids and production which detoxifies H2O2 into H2O and O2. RPE functions of energy (Fig. 1) (3, 4). In addition, a majority of the in the PPP, catalyzing the reversible conversion of NADPH used by the human body for biosynthetic D-ribulose 5-phosphate to D-xylulose 5-phosphate and is purposes is supplied by the PPP (5). Interestingly, RPE an important enzyme for cellular response against has been shown to protect cells from oxidative stress via oxidative stress. Here, using structural, biochemical, its participation in PPP for the production of NADPH and functional studies, we show that human D-ribulose (6–8). The protection against reactive oxygen species is ؉ 5-phosphate 3-epimerase (hRPE) uses Fe2 for cataly- exerted by NADPH’s ability to reduce glutathione, sis. Structures of the binary complexes of hRPE with which detoxifies H2O2 into H2O (Fig. 1). -

Ameyamaea Chiangmaiensis Gen. Nov., Sp. Nov., an Acetic Acid Bacterium in the -Proteobacteria

Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem., 73 (10), 2156–2162, 2009 Ameyamaea chiangmaiensis gen. nov., sp. nov., an Acetic Acid Bacterium in the -Proteobacteria Pattaraporn YUKPHAN,1 Taweesak MALIMAS,1 Yuki MURAMATSU,2 Mai TAKAHASHI,2 Mika KANEYASU,2 Wanchern POTACHAROEN,1 Somboon TANASUPAWAT,3 Yasuyoshi NAKAGAWA,2 Koei HAMANA,4 Yasutaka TAHARA,5 Ken-ichiro SUZUKI,2 y Morakot TANTICHAROEN,1 and Yuzo YAMADA1; ,* 1BIOTEC Culture Collection (BCC), National Center for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology (BIOTEC), Pathumthani 12120, Thailand 2Biological Resource Center (NBRC), Department of Biotechnology, National Institute of Technology and Evaluation (NITE), Kisarazu 292-0818, Japan 3Department of Microbiology, Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok 10330, Thailand 4School of Health Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, Gunma University, Maebashi 371-8514, Japan 5Department of Applied Biological Chemistry, Faculty of Agriculture, Shizuoka University, Shizuoka 422-8529, Japan Received January 27, 2009; Accepted July 8, 2009; Online Publication, October 7, 2009 [doi:10.1271/bbb.90070] Two isolates, AC04T and AC05, were isolated from Key words: Ameyamaea chiagmaiensis gen. nov., sp. the flowers of red ginger collected in Chiang Mai, nov.; acetic acid bacteria; 16S rRNA gene Thailand. In phylogenetic trees based on 16S rRNA sequences; 16S rRNA gene restriction anal- gene sequences, the two isolates were included within a ysis; Acetobacteraceae lineage comprised of the genera Acidomonas, Glucona- cetobacter, Asaia, Kozakia, Swaminathania, Neoasaia, In acetic acid bacteria, several new genera have been Granulibacter, and Tanticharoenia, and they formed an reported for strains isolated from isolation sources independent cluster along with the type strain of obtained in Southeast Asia. The first was the genus Tanticharoenia sakaeratensis. -

Carbohydrates: Structure and Function

CARBOHYDRATES: STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION Color index: . Very important . Extra Information. “ STOP SAYING I WISH, START SAYING I WILL” 435 Biochemistry Team *هذا العمل ﻻ يغني عن المصدر المذاكرة الرئيسي • The structure of carbohydrates of physiological significance. • The main role of carbohydrates in providing and storing of energy. • The structure and function of glycosaminoglycans. OBJECTIVES: 435 Biochemistry Team extra information that might help you 1-synovial fluid: - It is a viscous, non-Newtonian fluid found in the cavities of synovial joints. - the principal role of synovial fluid is to reduce friction between the articular cartilage of synovial joints during movement O 2- aldehyde = terminal carbonyl group (RCHO) R H 3- ketone = carbonyl group within (inside) the compound (RCOR’) 435 Biochemistry Team the most abundant organic molecules in nature (CH2O)n Carbohydrates Formula *hydrate of carbon* Function 1-provides important part of energy Diseases caused by disorders of in diet . 2-Acts as the storage form of energy carbohydrate metabolism in the body 3-structural component of cell membrane. 1-Diabetesmellitus. 2-Galactosemia. 3-Glycogen storage disease. 4-Lactoseintolerance. 435 Biochemistry Team Classification of carbohydrates monosaccharides disaccharides oligosaccharides polysaccharides simple sugar Two monosaccharides 3-10 sugar units units more than 10 sugar units Joining of 2 monosaccharides No. of carbon atoms Type of carbonyl by O-glycosidic bond: they contain group they contain - Maltose (α-1, 4)= glucose + glucose -Sucrose (α-1,2)= glucose + fructose - Lactose (β-1,4)= glucose+ galactose Homopolysaccharides Heteropolysaccharides Ketone or aldehyde Homo= same type of sugars Hetero= different types Ketose aldose of sugars branched unBranched -Example: - Contains: - Contains: Examples: aldehyde group glycosaminoglycans ketone group. -

Dissection of Exopolysaccharide Biosynthesis in Kozakia Baliensis Julia U

Brandt et al. Microb Cell Fact (2016) 15:170 DOI 10.1186/s12934-016-0572-x Microbial Cell Factories RESEARCH Open Access Dissection of exopolysaccharide biosynthesis in Kozakia baliensis Julia U. Brandt, Frank Jakob*, Jürgen Behr, Andreas J. Geissler and Rudi F. Vogel Abstract Background: Acetic acid bacteria (AAB) are well known producers of commercially used exopolysaccharides, such as cellulose and levan. Kozakia (K.) baliensis is a relatively new member of AAB, which produces ultra-high molecular weight levan from sucrose. Throughout cultivation of two K. baliensis strains (DSM 14400, NBRC 16680) on sucrose- deficient media, we found that both strains still produce high amounts of mucous, water-soluble substances from mannitol and glycerol as (main) carbon sources. This indicated that both Kozakia strains additionally produce new classes of so far not characterized EPS. Results: By whole genome sequencing of both strains, circularized genomes could be established and typical EPS forming clusters were identified. As expected, complete ORFs coding for levansucrases could be detected in both Kozakia strains. In K. baliensis DSM 14400 plasmid encoded cellulose synthase genes and fragments of truncated levansucrase operons could be assigned in contrast to K. baliensis NBRC 16680. Additionally, both K. baliensis strains harbor identical gum-like clusters, which are related to the well characterized gum cluster coding for xanthan synthe- sis in Xanthomanas campestris and show highest similarity with gum-like heteropolysaccharide (HePS) clusters from other acetic acid bacteria such as Gluconacetobacter diazotrophicus and Komagataeibacter xylinus. A mutant strain of K. baliensis NBRC 16680 lacking EPS production on sucrose-deficient media exhibited a transposon insertion in front of the gumD gene of its gum-like cluster in contrast to the wildtype strain, which indicated the essential role of gumD and of the associated gum genes for production of these new EPS. -

PENTOSE PHOSPHATE PATHWAY — Restricted for Students Enrolled in MCB102, UC Berkeley, Spring 2008 ONLY

Metabolism Lecture 5 — PENTOSE PHOSPHATE PATHWAY — Restricted for students enrolled in MCB102, UC Berkeley, Spring 2008 ONLY Bryan Krantz: University of California, Berkeley MCB 102, Spring 2008, Metabolism Lecture 5 Reading: Ch. 14 of Principles of Biochemistry, “Glycolysis, Gluconeogenesis, & Pentose Phosphate Pathway.” PENTOSE PHOSPHATE PATHWAY This pathway produces ribose from glucose, and it also generates 2 NADPH. Two Phases: [1] Oxidative Phase & [2] Non-oxidative Phase + + Glucose 6-Phosphate + 2 NADP + H2O Ribose 5-Phosphate + 2 NADPH + CO2 + 2H ● What are pentoses? Why do we need them? ◦ DNA & RNA ◦ Cofactors in enzymes ● Where do we get them? Diet and from glucose (and other sugars) via the Pentose Phosphate Pathway. ● Is the Pentose Phosphate Pathway just about making ribose sugars from glucose? (1) Important for biosynthetic pathways using NADPH, and (2) a high cytosolic reducing potential from NADPH is sometimes required to advert oxidative damage by radicals, e.g., ● - ● O2 and H—O Metabolism Lecture 5 — PENTOSE PHOSPHATE PATHWAY — Restricted for students enrolled in MCB102, UC Berkeley, Spring 2008 ONLY Two Phases of the Pentose Pathway Metabolism Lecture 5 — PENTOSE PHOSPHATE PATHWAY — Restricted for students enrolled in MCB102, UC Berkeley, Spring 2008 ONLY NADPH vs. NADH Metabolism Lecture 5 — PENTOSE PHOSPHATE PATHWAY — Restricted for students enrolled in MCB102, UC Berkeley, Spring 2008 ONLY Oxidative Phase: Glucose-6-P Ribose-5-P Glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase. First enzymatic step in oxidative phase, converting NADP+ to NADPH. Glucose 6-phosphate + NADP+ 6-Phosphoglucono-δ-lactone + NADPH + H+ Mechanism. Oxidation reaction of C1 position. Hydride transfer to the NADP+, forming a lactone, which is an intra-molecular ester. -

Kozakia Baliensis Gen. Nov., Sp. Nov., a Novel Acetic Acid Bacterium in The

International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology (2002), 52, 813–818 DOI: 10.1099/ijs.0.01982-0 Kozakia baliensis gen. nov., sp. nov., a novel NOTE acetic acid bacterium in the α-Proteobacteria 1 Laboratory of General and Puspita Lisdiyanti,1 Hiroko Kawasaki,2 Yantyati Widyastuti,3 Applied Microbiology, 3 2 1 1 Department of Applied Susono Saono, Tatsuji Seki, Yuzo Yamada, † Tai Uchimura Biology and Chemistry, and Kazuo Komagata1 Faculty of Applied Bioscience, Tokyo University of Agriculture, Author for correspondence: Yuzo Yamada. Tel\Fax: j81 54 635 2316. 1-1-1 Sakuragaoka, e-mail: yamada-yuzo!mub.biglobe.ne.jp Setagaya-ku, Tokyo 156- 8502, Japan 2 The International Center Four bacterial strains were isolated from palm brown sugar and ragi collected for Biotechnology, Osaka in Bali and Yogyakarta, Indonesia, by an enrichment culture approach for University, 2-1 Yamadaoka, Suita, Osaka 565-0871, acetic acid bacteria. Phylogenetic analysis based on 16S rRNA gene sequences Japan showed that the four isolates constituted a cluster separate from the genera 3 Research and Development Acetobacter, Gluconobacter, Acidomonas, Gluconacetobacter and Asaia with a Centre for Biotechnology, high bootstrap value in a phylogenetic tree. The isolates had high values of Indonesian Institute of DNA–DNA similarity (78–100%) between one another and low values of the Sciences (LIPI), Jalan Raya Bogor Km 46, Cibinong similarity (7–25%) to the type strains of Acetobacter aceti, Gluconobacter 16911, Indonesia oxydans, Gluconacetobacter liquefaciens and Asaia bogorensis. The DNA base composition of the isolates ranged from 568to572 mol% GMC with a range of 04 mol%. The major quinone was Q-10. -

Open NAL Thesis V6.Pdf

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering CLASSIFICATION OF POLYPHOSPHATE-ACCUMULATING BACTERIA IN BENTHIC BIOFILMS A Thesis in Environmental Engineering by Nicholas Locke 2015 Nicholas Locke Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science August 2015 ii The thesis of Nicholas Locke was reviewed and approved* by the following: John Regan Professor of Environmental Engineering Thesis Advisor William Burgos Professor of Environmental Engineering Chair of Civil and Environmental Engineering Graduate Programs Anthony Buda Adjunct Assistant Professor of Ecosystem Science and Management *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School iii ABSTRACT Polyphosphate accumulating organisms (PAOs) are microorganisms known to store excess phosphorus (P) as polyphosphate (poly-P) in environments subject to alternating aerobic and anaerobic conditions. There has been considerable research on PAOs in biological wastewater treatment systems, but very little investigation of these microbes in freshwater systems. We hypothesize that putative PAOs in benthic biofilms of shallow streams where daily light cycles induce alternating aerobic and anaerobic conditions are similar to those found in EBPR. To test this hypothesis, cells with poly-P inclusions were isolated, classified, and described. Eight benthic biofilms taken from a first-order stream in Mahantango Creek Watershed (Klingerstown, PA) represented high and low P loadings from a series of four flumes and were found to contain 0.39 - 6.19% PAOs. A second set of eight benthic biofilms from locations selected by Carrick and Price (2011) were from third- order streams in Pennsylvania and contained 11-48% putative PAOs based on flow cytometry particle counts. -

Ii- Carbohydrates of Biological Importance

Carbohydrates of Biological Importance 9 II- CARBOHYDRATES OF BIOLOGICAL IMPORTANCE ILOs: By the end of the course, the student should be able to: 1. Define carbohydrates and list their classification. 2. Recognize the structure and functions of monosaccharides. 3. Identify the various chemical and physical properties that distinguish monosaccharides. 4. List the important monosaccharides and their derivatives and point out their importance. 5. List the important disaccharides, recognize their structure and mention their importance. 6. Define glycosides and mention biologically important examples. 7. State examples of homopolysaccharides and describe their structure and functions. 8. Classify glycosaminoglycans, mention their constituents and their biological importance. 9. Define proteoglycans and point out their functions. 10. Differentiate between glycoproteins and proteoglycans. CONTENTS: I. Chemical Nature of Carbohydrates II. Biomedical importance of Carbohydrates III. Monosaccharides - Classification - Forms of Isomerism of monosaccharides. - Importance of monosaccharides. - Monosaccharides derivatives. IV. Disaccharides - Reducing disaccharides. - Non- Reducing disaccharides V. Oligosaccarides. VI. Polysaccarides - Homopolysaccharides - Heteropolysaccharides - Carbohydrates of Biological Importance 10 CARBOHYDRATES OF BIOLOGICAL IMPORTANCE Chemical Nature of Carbohydrates Carbohydrates are polyhydroxyalcohols with an aldehyde or keto group. They are represented with general formulae Cn(H2O)n and hence called hydrates of carbons. -

Monosaccharides

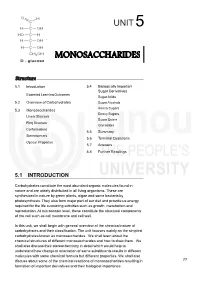

UNIT 5 MONOSACCHARIDES Structure 5.1 Introduction 5.4 Biologically Important Sugar Derivatives Expected Learning Outcomes Sugar Acids 5.2 Overview of Carbohydrates Sugar Alcohols Amino Sugars 5.3 Monosaccharides Deoxy Sugars Linear Structure Sugar Esters Ring Structure Glycosides Conformations 5.5 Summary Stereoisomers 5.6 Terminal Questions Optical Properties 5.7 Answers 5.8 Further Readings 5.1 INTRODUCTION Carbohydrates constitute the most abundant organic molecules found in nature and are widely distributed in all living organisms. These are synthesized in nature by green plants, algae and some bacteria by photosynthesis. They also form major part of our diet and provide us energy required for the life sustaining activities such as growth, metabolism and reproduction. At microscopic level, these constitute the structural components of the cell such as cell membrane and cell wall. In this unit, we shall begin with general overview of the chemical nature of carbohydrates and their classification. The unit focuses mainly on the simplest carbohydrates known as monosaccharides. We shall learn about the chemical structures of different monosaccharides and how to draw them. We shall also discuss their stereochemistry in detail which would help to understand how change in orientation of same substituents results in different molecules with same chemical formula but different properties. We shall also discuss about some of the chemical reactions of monosaccharides resulting in 77 formation of important derivatives and their biological importance. -

Production of Prebiotic Exopolysaccharides by Lactobacilli

Lehrstuhl für Technische Mikrobiologie Production of prebiotic exopolysaccharides by lactobacilli Markus Tieking Vollständiger Abdruck der von der Fakultät Wissenschaftszentrum Weihenstephan für Ernährung, Landnutzung und Umwelt der Technischen Universität München zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Doktor - Ingenieurs genehmigten Dissertation. Vorsitzender: Univ.-Prof. Dr.- Ing. E. Geiger Prüfer der Dissertation: 1. Univ.-Prof. Dr. rer. nat. habil. R. F. Vogel 2. Univ.-Prof. Dr.- Ing. D. Weuster-Botz Die Dissertation wurde am 09.03.2005 bei der Technischen Universität eingereicht und durch die Fakultät Wissenschaftszentrum Weihenstephan für Ernährung, Landnutzung und Umwelt am 27.05.2005 angenommen. Lehrstuhl für Technische Mikrobiologie Production of prebiotic exopolysaccharides by lactobacilli Markus Tieking Doctoral thesis Fakultät Wissenschaftszentrum Weihenstephan für Ernährung, Landnutzung und Umwelt Freising 2005 Mein Dank gilt meinem Doktorvater Prof. Rudi Vogel für die Überlassung des Themas sowie die stete Diskussionsbereitschaft, Dr. Michael Gänzle für die kritische Begleitung, die ständige Diskussionsbereitschaft sowie sein fachliches Engagement, welches weit über das übliche Maß hinaus geht, Dr. Matthias Ehrmann für seine uneingeschränkte Bereitwilligkeit, sein Wissen auf dem Gebiet der Molekularbiologie weiterzugeben, seine unschätzbar wertvollen praktischen Ratschläge auf diesem Gebiet sowie für seine Geduld, meiner lieben Frau Manuela, deren Motivationskünste und emotionale Unterstützung mir wissenschaftliche