Victoria Woodhull: a Radical for Free Love Bernice Redfern

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sickly Sentimentalism: Sympathy and Pathology in American Women's Literature, 1866-1900

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 5-2018 Sickly Sentimentalism: Sympathy and Pathology in American Women's Literature, 1866-1900 Nicole Zeftel The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2613 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] SICKLY SENTIMENTALISM: SYMPATHY AND PATHOLOGY IN AMERICAN WOMEN’S LITERATURE, 1866-1900 by NICOLE ZEFTEL A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Comparative Literature in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2018 © 2018 NICOLE ZEFTEL All Rights Reserved ! ii! Sickly Sentimentalism: Sympathy and Pathology in American Women’s Literature, 1866-1900 by Nicole Zeftel This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Comparative Literature in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date ! Hildegard Hoeller Chair of Examining Committee Date ! Giancarlo Lombardi Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Eric Lott Bettina Lerner THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK ! iii! ABSTRACT Sickly Sentimentalism: Sympathy and Pathology in American Women’s Literature, 1866-1900 by Nicole Zeftel Advisors: Hildegard Hoeller and Eric Lott Sickly Sentimentalism: Pathology and Sympathy in American Women’s Literature, 1866-1900 examines the work of four American women novelists writing between 1866 and 1900 as responses to a dominant medical discourse that pathologized women’s emotions. -

Reading Guide Other Powers

Reading Guide Other Powers By Barbara Goldsmith ISBN: 9780060953324 Plot Summary Other Powers: The Age of Suffrage, Spiritualism, and the Scandalous Victoria Woodhull is a portrait of the tumultuous last half of the nineteenth century, when the United States experienced the Civil War, Reconstruction, Andrew Johnson's impeachment trial, and the 1869 collapse of the gold market. A stunning combination of history and biography, Other Powers interweaves the stories of the important social, political, and religious players of America's Victorian era with the scandalous life of Victoria Woodhull--Spiritualist, woman's rights crusader, free-love advocate, stockbroker, prostitute, and presidential candidate. This is history at its most vivid, set amid the battle for woman suffrage, the Spiritualist movement that swept across the nation in the age of Radical Reconstruction following the Civil War, and the bitter fight that pitted black men against white women in the struggle for the right to vote. The book's cast: Victoria Woodhull, billed as a clairvoyant and magnetic healer--a devotee and priestess of those "other powers" that were gaining acceptance across America--in her father's traveling medicine show . spiritual and financial advisor to Commodore Vanderbilt . the first woman to address a joint session of Congress, where--backed by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony--she presents an argument that women, as citizens, should have the right to vote . becoming the "high priestess" of free love in America (fiercely believing the then-heretical idea that women should have complete sexual equality with men) . making a run for the presidency of the United States against Horace Greeley and Ulysses S. -

Religion in the American Suffrage Movement, 1848-1895 Elizabeth B

Boston University School of Law Scholarly Commons at Boston University School of Law Publications Betsy Clark Living Archive 10-1989 The olitP ics of God and the Woman's Vote: Religion in the American Suffrage Movement, 1848-1895 Elizabeth B. Clark Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.bu.edu/clark_pubs Part of the Family Law Commons, and the Legal History Commons Recommended Citation Elizabeth B. Clark, The Politics of God and the Woman's Vote: Religion in the American Suffrage Movement, 1848-1895, (1989). Available at: https://scholarship.law.bu.edu/clark_pubs/3 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Betsy Clark Living Archive at Scholarly Commons at Boston University School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons at Boston University School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE POLITICS OF GOD AND THE WOMAN'S VOTE: RELIGION IN THE AMERICAN SUFFRAGE MOVEMENT, 1848-1895 Elizabeth Battelle Clark A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE FACULTY OF PRINCETON UNIVERSITY IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY RECOMMENDED FOR ACCEPTANCE BY THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY October, 1989 © Copyright by Elizabeth Battelle Clark 1989 All Rights Reserved Thesis Abstract This thesis examines the role of religion— both liberal and evangelical Protestantism— in the development of a feminist political theory in America during the nineteenth century and how that feminist theory in turn helped to transform American liberalism. Chapter 1 looks for the genesis of women's rights language, not in the republican rhetoric of the Founding Fathers, but in the teachings of liberal Protestantism and its links with laissez-faire economic theory. -

The Right of Way

The Right of Way Gilbert Parker The Right of Way Table of Contents The Right of Way......................................................................................................................................................1 Gilbert Parker.................................................................................................................................................1 INTRODUCTION.........................................................................................................................................2 NOTE.............................................................................................................................................................5 CHAPTER I. THE WAY TO THE VERDICT.............................................................................................5 CHAPTER II. WHAT CAME OF THE TRIAL............................................................................................9 CHAPTER III. AFTER FIVE YEARS........................................................................................................15 CHAPTER IV. CHARLEY MAKES A DISCOVERY...............................................................................17 CHAPTER V. THE WOMAN IN HELIOTROPE......................................................................................18 CHAPTER VI. THE WIND AND THE SHORN LAMB...........................................................................21 CHAPTER VII. PEACE, PEACE, AND THERE IS NO PEACE"'.........................................................25 -

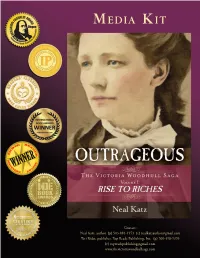

Mediately Draws You in with Believable Dialogue and a Subject Matter That Makes You Want to Know More

M EDIA KIT Contact: Neal Katz, author (p) 503-883-1973 (e) [email protected] Teri Rider, publisher, Top Reads Publishing, Inc. (p) 760-458-9393 (e) [email protected] www.thevictoriawoodhullsaga.com Complete listing of Awards Won – Outrageous, The Victoria Woodhull Saga, Volume 1: Rise to Riches (to date, April 16, 2017) Outrageous has won 9 major National Awards for Independent Publishing, and 1 International Award in a field of all published books. Individual awards listed below. IBPA Benjamin Franklin – Bill Fisher Award for Best First Book by a Publisher, Gold Medal http://iBpaBenjaminfranklinawards.com/2016-ibpa-bfa-finalists/#Bill1 Video interview: https://youtu.Be/2HQJ8tF1niI?list=PL0j72Ir-3hZEAu91MJ9lVwLYFuaPFPUZ4 Independent Publisher Book Awards, IPPY – Gold Medal for Best Historical Fiction http://www.independentpublisher.com/article.php?page=2045 Reader’s Favorite – Gold Medal for Best Historical Fiction / Personage https://readersfavorite.com/book-review/outrageous International Book Awards – Winner, Best New Fiction http://www.internationalbookawards.com/2016awardannouncement.html Indie Reader Discovery Award – Second Place Winner in Fiction http://indiereader.com/indiereader-discovery-awards/past-winners/ Next Generation Indie Book Award – Finalist Historical Fiction http://www.indieBookawards.com/winners/2016 Independent Author Network (IAN) Book of the Year Awards – Finalist in Two Categories: Historical Fiction, First Novel http://www.independentauthornetwork.com/2016-book-of-the-year-winners.html Chanticleer -

Early Women of Wall Street: “Sports of Nature” Shirley M. Mueller Published on Health Care Professionals Live August 3, 2009

Early Women of Wall Street: “Sports of Nature” Shirley M. Mueller Published on Health Care Professionals Live August 3, 2009 “Woman's ability to earn money is better protection against the tyranny and brutality of men than her ability to vote," said Victoria Woodhull in the late 19th century. This independence on the part of the Woodhull marked her as a „sport of nature,‟ by Eunice Barnard in an article she wrote in the April, 1929 North American Review. Hetty Green, also a nineteenth century financial pioneer, was similarly designated. Currently these „sports of nature‟ are receiving attention in “Women of Wall Street,” an exhibit at the Museum of American Finance in New York City running until January 16, 2010. Since learning from the past can inform the future, reviewing the exhibit is not only informative and interesting, but could be helpful to investors who seek to emulate successful predecessors. The two „sports of nature,‟ which Barnard referred to, were different than other women of their time. Their qualities of independence, self determination and ability to focus were not necessarily welcomed by all of their contemporaries. Still, these were the traits that no doubt lead to their investing genius. Victoria Woodhull, along with her sister, Tennessee Claflin, opened the first female brokerage house on Wall Street in 1870. Though the girls were from a poor home in Ohio, they did whatever was necessary to improve their lot in life. It is said that Victoria was a prostitute for a while to earn extra money. No matter what the details, she and Tennessee started Woodhull, Claflin and Company in 1870 with backing from Cornelius Vanderbilt. -

Numbered Pages

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Maddening Truths: Literary Authority and Fictive Authenticity in Francophone and Post-Soviet Women’s Writing A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature by Melanie Veronica Jones 2021 © Copyright by Melanie Veronica Jones 2021 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Maddening Truths: Literary Authority and Fictive Authenticity in Francophone and Post-Soviet Women’s Writing by Melanie Veronica Jones Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature University of California, Los Angeles, 2021 Professor David MacFadyen, Co-Chair Professor Laure Murat, Co-Chair At the start of the “post-truth” era, women writers in post-colonial France and post-Soviet Russia were searching for a strategy to respond to the crises of authority and authenticity unfolding around them. Linda Lê, Gisèle Pineau, Ludmilla Petrushevskaya, and Anna Starobinets exploit the ambiguity of literary madness to destabilize traditional sites of knowledge and work towards new conceptions of truth. All four women’s works have traditionally been approached as narratives of trauma, detailing the ravages of mental illness or cultural upheaval. This dissertation argues that they instead work to expose the irreconcilability of medical, sociological, and spiritual authorities, forcing readers to constantly question who (if anyone) can be considered trustworthy and which ii (if any) perspective can be declared reliable. The texts provide fictional reference points, like intertextual allusions and meta-literary framing, as the surest way for readers to anchor their assumptions. Linda Lê’s autofictional text Calomnies and Gisèle Pineau’s autobiographical novel Chair Piment depict a Francophone world wracked with social fractures in the wake of decolonization and economic crisis: amidst the splintering chaos, literature acts as a tenuous web holding contradictory discourses in suspension. -

Nsanders, 8Everlv Educational Equity Act Program. 74P.: For,Relatea Documenti, See SO 012 593-594 and (Groups): *Reconstruction

r DOCUMENT DESIIME ED 186 342 ,S0 012595'. AUTHOR NSanders, 8everlv , TITLE Women in American History: A Series. Book Three,- Womenk'during and after the Civil War 1860.r1890. INSTITUTION AmeriCan Federaticin of TeaChers, Washington, D.C. SPONS AGSNCY 'Office of -Pducaticn (DHEW),.WashAngton, D.C. Womemusr Educational Equity Act Program. PUB DATE 79 NOTE 74p.: For,relatea documenti, see SO 012 593-594 and ,ISID 012 596. I AVAILABLE FROM Education Devillopment. Center, 5S,Chapel Street, Newtonc MA 02`160 ($1.50 plus $1-.30 shippimg Set charge) . EDRS PR/CE MF01 Plus Postage. PC Not Available'frpm EDRS. DESCRIPTORS *Civil WaT (United°States) :*Females; Teminism; .4Learaing Activities: Occupations; Organizations (Groups): *Reconstruction Era: Secondary Educatio; Sex Discrimination: *Sex Role; Slavery; Sccial Action: Social Studies; Teachers; United States History; Womens Educatipn: *Womens Studies ABSTRACT The document, one in a series og four on women in American history, discusses the role of women during and after the Civil War' (1860-1890). Designed to supplement high school U.S. ,historYitextboks, the book is comprised of five.charters. glapter a describes the work of Union and Confederate wcmen ln the Civil W. Topics include the army nursing service, women in the militarYi'and - women who assumed the responsibilities of their absent husbahds. Chapter.II focuses on black and wfiite women educators for the freed slaves duritg the Reconstruction Era. Excerpts from diaries reveal the experiences of these teachers. Chapter III describes woien on.the western frontier. Again, excerpts from letters and diaries depict the °fewis and tlark guide, Sacalawea: pioneer missionaries adjusting to frontier life: and the experiences of women on the Western trail. -

Daxer & M Arschall 20 19 XXVI

XXVI Daxer & Marschall 2019 Recent Acquisitions, Catalogue XXVI, 2019 Barer Strasse 44 | 80799 Munich | Germany Tel. +49 89 28 06 40 | Fax +49 89 28 17 57 | Mob. +49 172 890 86 40 [email protected] | www.daxermarschall.com 2 Oil Sketches, Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, 1668-1917 4 My special thanks go to Simone Brenner and Diek Groenewald for their research and their work on the texts. I am also grateful to them for so expertly supervising the production of the catalogue. We are much indebted to all those whose scholarship and expertise have helped in the preparation of this catalogue. In particular, our thanks go to: Peter Axer, Iris Berndt, Robert Bryce, Christine Buley-Uribe, Sue Cubitt, Kilian Heck, Wouter Kloek, Philipp Mansmann, Verena Marschall, Werner Murrer, Otto Naumann, Peter Prange, Dorothea Preys, Eddy Schavemaker, Annegret Schmidt- Philipps, Ines Schwarzer, Gerd Spitzer, Andreas Stolzenburg, Jörg Trempler, Jana Vedra, Vanessa Voigt, Wolf Zech. 6 Our latest catalogue Oil Sketches, Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, 2019 Unser diesjähriger Katalog Paintings, Oil Sketches, comes to you in good time for this year’s TEFAF, The European Fine Art Fair in Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, 2019 erreicht Sie Maastricht. TEFAF is the international art market high point of the year. It runs rechtzeitig vor dem wichtigsten Kunstmarktereignis from March 16-24, 2019. des Jahres, TEFAF, The European Fine Art Fair, Maastricht, 16. - 24. März 2019, auf der wir mit Stand The Golden Age of seventeenth-century Dutch painting is well represented in 332 vertreten sind. our 2019 catalogue, with particularly fine works by Jan van Mieris and Jan Steen. -

Lucy Hargrett Draper Center and Archives for the Study of the Rights

Lucy Hargrett Draper Center and Archives for the Study of the Rights of Women in History and Law Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library Special Collections Libraries University of Georgia Index 1. Legal Treatises. Ca. 1575-2007 (29). Age of Enlightenment. An Awareness of Social Justice for Women. Women in History and Law. 2. American First Wave. 1849-1949 (35). American Pamphlets timeline with Susan B. Anthony’s letters: 1853-1918. American Pamphlets: 1849-1970. 3. American Pamphlets (44) American pamphlets time-line with Susan B. Anthony’s letters: 1853-1918. 4. American Pamphlets. 1849-1970 (47). 5. U.K. First Wave: 1871-1908 (18). 6. U.K. Pamphlets. 1852-1921 (15). 7. Letter, autographs, notes, etc. U.S. & U.K. 1807-1985 (116). 8. Individual Collections: 1873-1980 (165). Myra Bradwell - Susan B. Anthony Correspondence. The Emily Duval Collection - British Suffragette. Ablerta Martie Hill Collection - American Suffragist. N.O.W. Collection - West Point ‘8’. Photographs. Lucy Hargrett Draper Personal Papers (not yet received) 9. Postcards, Woman’s Suffrage, U.S. (235). 10. Postcards, Women’s Suffrage, U.K. (92). 11. Women’s Suffrage Advocacy Campaigns (300). Leaflets. Broadsides. Extracts Fliers, handbills, handouts, circulars, etc. Off-Prints. 12. Suffrage Iconography (115). Posters. Drawings. Cartoons. Original Art. 13. Suffrage Artifacts: U.S. & U.K. (81). 14. Photographs, U.S. & U.K. Women of Achievement (83). 15. Artifacts, Political Pins, Badges, Ribbons, Lapel Pins (460). First Wave: 1840-1960. Second Wave: Feminist Movement - 1960-1990s. Third Wave: Liberation Movement - 1990-to present. 16. Ephemera, Printed material, etc (114). 17. U.S. & U.K. -

Reuben Buckman

1 Reuben Buckman “Buck” Claflin Born about 1796 in Massachusetts.1 Died 19 November 1885, Kensington, London, Middlesex, England.2 Buried 24 November 1885, Highgate Cemetery West, London, Middlesex, England3 Buck was the son of Robert Claflin and Anna Underwood.4 No record of his birth has been found but most census enumerations identify Massachusetts as his place of birth and allow for a near calculation of his birth year.5 It is known that his grandfather and father had been in Westhampton, in Hampshire County, then they were in the Sandisfield area of what became Berkshire County where some of the family lived out their lives. Buck’s father later moved to Troy, Bedford County, Pennsylvania around 1800. The complex borders between Hampshire, Hampden, and Berkshire Counties in Massachusetts, together with New York’s Columbia County and Connecticut’s Harford County have frustrated genealogists for years. This coupled with the difficulties in this area following the Revolution,6 make establishing genealogical evidence extremely difficult and time-consuming. There is no doubt that Buck has the worst reputation of anyone involved in the Woodhull story and has become a grotesque caricature.7 There is also no doubt he was a many-faceted individual, often an opportunist, with an entrepreneurial bent. Buck certainly had his faults, but it must be remembered he was the father of, and had a life- long relationship with, two of the most remarkable women of the Gilded Age, Victoria Woodhull and Tennessee Claflin. His modern reputation of a conniving, child abusing, snake-oil-peddling, petty thief, and con man all come from Woodhull’s biography by Theodore Tilton. -

Seeing Laure: Race and Modernity from Manet's Olympia to Matisse

Seeing Laure: Race and Modernity from Manet’s Olympia to Matisse, Bearden and Beyond Denise M. Murrell Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2014 © 2013 Denise M. Murrell All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Seeing Laure: Race and Modernity from Manet’s Olympia to Matisse, Bearden and Beyond Denise M. Murrell During the 1860s in Paris, Edouard Manet and his circle transformed the style and content of art to reflect an emerging modernity in the social, political and economic life of the city. Manet’s Olympia (1863) was foundational to the new manner of painting that captured the changing realities of modern life in Paris. One readily observable development of the period was the emergence of a small but highly visible population of free blacks in the city, just fifteen years after the second and final French abolition of territorial slavery in 1848. The discourse around Olympia has centered almost exclusively on one of the two figures depicted: the eponymous prostitute whose portrayal constitutes a radical revision of conventional images of the courtesan. This dissertation will attempt to provide a sustained art-historical treatment of the second figure, the prostitute’s black maid, posed by a model whose name, as recorded by Manet, was Laure. It will first seek to establish that the maid figure of Olympia, in the context of precedent and Manet’s other images of Laure, can be seen as a focal point of interest, and as a representation of the complex racial dimension of modern life in post-abolition Paris.