Religion in the American Suffrage Movement, 1848-1895 Elizabeth B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anarchism and Religion

Anarchism and Religion Nicolas Walter 1991 For the present purpose, anarchism is defined as the political and social ideology which argues that human groups can and should exist without instituted authority, and especially as the historical anarchist movement of the past two hundred years; and religion is defined as the belief in the existence and significance of supernatural being(s), and especially as the prevailing Judaeo-Christian systemof the past two thousand years. My subject is the question: Is there a necessary connection between the two and, if so, what is it? The possible answers are as follows: there may be no connection, if beliefs about human society and the nature of the universe are quite independent; there may be a connection, if such beliefs are interdependent; and, if there is a connection, it may be either positive, if anarchism and religion reinforce each other, or negative, if anarchism and religion contradict each other. The general assumption is that there is a negative connection logical, because divine andhuman authority reflect each other; and psychological, because the rejection of human and divine authority, of political and religious orthodoxy, reflect each other. Thus the French Encyclopdie Anarchiste (1932) included an article on Atheism by Gustave Brocher: ‘An anarchist, who wants no all-powerful master on earth, no authoritarian government, must necessarily reject the idea of an omnipotent power to whom everything must be subjected; if he is consistent, he must declare himself an atheist.’ And the centenary issue of the British anarchist paper Freedom (October 1986) contained an article by Barbara Smoker (president of the National Secular Society) entitled ‘Anarchism implies Atheism’. -

Sickly Sentimentalism: Sympathy and Pathology in American Women's Literature, 1866-1900

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 5-2018 Sickly Sentimentalism: Sympathy and Pathology in American Women's Literature, 1866-1900 Nicole Zeftel The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2613 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] SICKLY SENTIMENTALISM: SYMPATHY AND PATHOLOGY IN AMERICAN WOMEN’S LITERATURE, 1866-1900 by NICOLE ZEFTEL A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Comparative Literature in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2018 © 2018 NICOLE ZEFTEL All Rights Reserved ! ii! Sickly Sentimentalism: Sympathy and Pathology in American Women’s Literature, 1866-1900 by Nicole Zeftel This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Comparative Literature in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date ! Hildegard Hoeller Chair of Examining Committee Date ! Giancarlo Lombardi Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Eric Lott Bettina Lerner THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK ! iii! ABSTRACT Sickly Sentimentalism: Sympathy and Pathology in American Women’s Literature, 1866-1900 by Nicole Zeftel Advisors: Hildegard Hoeller and Eric Lott Sickly Sentimentalism: Pathology and Sympathy in American Women’s Literature, 1866-1900 examines the work of four American women novelists writing between 1866 and 1900 as responses to a dominant medical discourse that pathologized women’s emotions. -

Victoria Woodhull: a Radical for Free Love Bernice Redfern

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks San José Studies, 1980s San José Studies Fall 10-1-1984 San José Studies, Fall 1984 San José State University Foundation Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/sanjosestudies_80s Recommended Citation San José State University Foundation, "San José Studies, Fall 1984" (1984). San José Studies, 1980s. 15. https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/sanjosestudies_80s/15 This Journal is brought to you for free and open access by the San José Studies at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in San José Studies, 1980s by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. sa1an~s asof Nvs SAN JOSE Volume X, Number 3 ARTICLES The Declaration and the Constitution Harry V. Jaffa . 6 A Moral and a Religious People Robert N. Bellah .............................................. 12 The Constitution and Civic Education William J. Bennett ............................................ 18 Conversation: The Higher Law Edward J. Erler and T. M. Norton .............................. 22 Everyone Loves Money in The Merchant of Venice Norman Nathan .............................................. 31 Victoria Woodhull: A Radical for Free Love Bernice Redfern .............................................. 40 Goneril and Regan: 11So Horrid as in Woman" Claudette Hoover ............................................ 49 STUDIES Fall1984 FICTION The Homed Beast Robert Burdette Sweet ........................................ 66 Wars Dim and -

Reading Guide Other Powers

Reading Guide Other Powers By Barbara Goldsmith ISBN: 9780060953324 Plot Summary Other Powers: The Age of Suffrage, Spiritualism, and the Scandalous Victoria Woodhull is a portrait of the tumultuous last half of the nineteenth century, when the United States experienced the Civil War, Reconstruction, Andrew Johnson's impeachment trial, and the 1869 collapse of the gold market. A stunning combination of history and biography, Other Powers interweaves the stories of the important social, political, and religious players of America's Victorian era with the scandalous life of Victoria Woodhull--Spiritualist, woman's rights crusader, free-love advocate, stockbroker, prostitute, and presidential candidate. This is history at its most vivid, set amid the battle for woman suffrage, the Spiritualist movement that swept across the nation in the age of Radical Reconstruction following the Civil War, and the bitter fight that pitted black men against white women in the struggle for the right to vote. The book's cast: Victoria Woodhull, billed as a clairvoyant and magnetic healer--a devotee and priestess of those "other powers" that were gaining acceptance across America--in her father's traveling medicine show . spiritual and financial advisor to Commodore Vanderbilt . the first woman to address a joint session of Congress, where--backed by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony--she presents an argument that women, as citizens, should have the right to vote . becoming the "high priestess" of free love in America (fiercely believing the then-heretical idea that women should have complete sexual equality with men) . making a run for the presidency of the United States against Horace Greeley and Ulysses S. -

A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Satisfaction of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO PUBLIC CATHOLICISM AND RELIGIOUS PLURALISM IN AMERICA: THE ADAPTATION OF A RELIGIOUS CULTURE TO THE CIRCUMSTANCE OF DIVERSITY, AND ITS IMPLICATIONS A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology by Michael J. Agliardo, SJ Committee in charge: Professor Richard Madsen, Chair Professor John H. Evans Professor David Pellow Professor Joel Robbins Professor Gershon Shafir 2008 Copyright Michael J. Agliardo, SJ, 2008 All rights reserved. The Dissertation of Michael Joseph Agliardo is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Chair University of California, San Diego 2008 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page ......................................................................................................................... iii Table of Contents......................................................................................................................iv List Abbreviations and Acronyms ............................................................................................vi List of Graphs ......................................................................................................................... vii Acknowledgments ................................................................................................................. viii Vita.............................................................................................................................................x -

The Impact of the Communist Regime in Albania on Freedom of Religion for Albanians

ISSN 2039-2117 (online) Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences Vol 12 No 1 ISSN 2039-9340 (print) www.richtmann.org January 2021 . Research Article © 2021 Tokrri et.al.. This is an open access article licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) Received: 21 November 2020 / Accepted: 11 January 2021 / Published: 17 January 2021 The Impact of the Communist Regime in Albania on Freedom of Religion for Albanians Dr. Renata Tokrri Vice-Rector, Lecturer, University Aleksanër Moisiu, 14, 2001, Rruga Currila, Durrës, Albania Dr. Ismail Tafani Head, Lecturer, Department of Legal Sciences, Albanian University, Bulevardi Zogu I, Tirana 1001, Albania Dr. Aldo Shkembi Advocacy Chamber, Tirana, Albania DOI: https://doi.org/10.36941/mjss-2021-0004 Abstract The multi religions Albania passed last century from a country where atheism was the constitutional principle in a country where the basic card guarantees not only the freedom of religion but also the freedom from religion. Today, in order of guaranteeing the freedom of belief, the Constitution of Republic of Albania expresses principles which protect the religious freedom, starting from its preamble. Indeed, the preamble has no legal force but stated goals and assists in the interpretation of provisions. The spirit, with which the preamble stated, is that of tolerance and religious coexistence, in a vision where the people are responsible for the future with faith in God or other universal values. This statement reinforces the principle of secularism of the state where the latter appears as the guarantor of religious freedom by knowing in this perspective the beliefs that "sovereign" could have and can develop. -

James G. Blaine and Justice Clarence Thomas‟ „Bigotry Thesis

Forum on Public Policy Public Financing of Religious Schools: James G. Blaine and Justice Clarence Thomas‟ „Bigotry Thesis‟ Kern Alexander, Professor, Educational Organization and Leadership, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Abstract United States Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas writing for a plurality of the Court in Mitchell v. Helms in 2000 advanced the idea that state constitutional prohibitions against public funding of religious schools were manifestations of anti-Catholic bigotry in the late 19th century. Thomas‟ reading of history and law led him to believe that James G. Blaine a political leader in the United States of that era who advanced a proposed amendment to the U.S. Constitution that would have prohibited states from funding Catholic schools was himself imbued with anti-Catholic bigotry and that his proposed amendment was a well-spring of religious intolerance that today prevents public funding of Catholic schools. This article attempts to look further into the issue to determine whether Thomas‟ understanding is accurate and whether it comports with the reality of conditions of the era and whether Blaine in fact had such motivations as ascribed to him by Justice Thomas. The article concludes that Thomas‟ view is overly simplistic and is based on an insular perception of Protestant versus Catholic intolerance in the United States and leaves out of consideration the fact that the real and larger issue of the era in the western world was the struggle between secularism and sectarianism, modernity and tradition, science and superstition, and individual liberty and clerical control. Importantly, the article concludes that Thomas‟s narrow thesis ignores international dimensions of conflicts of the era that pitted the impulse of nationalism and republican government against control of ecclesiastics regardless of whether they were Catholic or Protestant. -

Political Islam: a 40 Year Retrospective

religions Article Political Islam: A 40 Year Retrospective Nader Hashemi Josef Korbel School of International Studies, University of Denver, Denver, CO 80208, USA; [email protected] Abstract: The year 2020 roughly corresponds with the 40th anniversary of the rise of political Islam on the world stage. This topic has generated controversy about its impact on Muslims societies and international affairs more broadly, including how governments should respond to this socio- political phenomenon. This article has modest aims. It seeks to reflect on the broad theme of political Islam four decades after it first captured global headlines by critically examining two separate but interrelated controversies. The first theme is political Islam’s acquisition of state power. Specifically, how have the various experiments of Islamism in power effected the popularity, prestige, and future trajectory of political Islam? Secondly, the theme of political Islam and violence is examined. In this section, I interrogate the claim that mainstream political Islam acts as a “gateway drug” to radical extremism in the form of Al Qaeda or ISIS. This thesis gained popularity in recent years, yet its validity is open to question and should be subjected to further scrutiny and analysis. I examine these questions in this article. Citation: Hashemi, Nader. 2021. Political Islam: A 40 Year Keywords: political Islam; Islamism; Islamic fundamentalism; Middle East; Islamic world; Retrospective. Religions 12: 130. Muslim Brotherhood https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12020130 Academic Editor: Jocelyne Cesari Received: 26 January 2021 1. Introduction Accepted: 9 February 2021 Published: 19 February 2021 The year 2020 roughly coincides with the 40th anniversary of the rise of political Islam.1 While this trend in Muslim politics has deeper historical and intellectual roots, it Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral was approximately four decades ago that this subject emerged from seeming obscurity to with regard to jurisdictional claims in capture global attention. -

A Comparative-Historical Sociology of Secularisation: Republican State Building in France (1875-1905) and Turkey (1908-1938)

A Comparative-Historical Sociology of Secularisation: Republican State Building in France (1875-1905) and Turkey (1908-1938) by Efe Peker MSc, Linköping University, 2006 Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Joint Degree (Cotutelle) of Doctor of Philosophy Sociology, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at Simon Fraser University (Canada) and History, Faculty of Human Sciences at Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne (France) © Efe Peker 2016 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY UNIVERSITÉ PARIS 1 PANTHÉON-SORBONNE Spring 2016 Approval Name: Efe Peker Degree: Doctor of Philosophy Title: A Comparative-Historical Sociology of Secularisation: Republican State Building in France (1875-1905) and Turkey (1908-1938) Examining Committee: Chair: Wendy Chan Professor Gary Teeple Senior Supervisor Professor Patrick Weil Senior Supervisor Professor Centre d’histoire sociale du XXème siècle Université Paris I Panthéon-Sorbonne Gerardo Otero Supervisor Professor School for International Studies Gilles Dorronsoro Internal Examiner Professor Political Science Université Paris I Panthéon-Sorbonne Rita Hermon-Belot External Examiner Professor History École des hautes études en sciences sociales Philip Gorski External Examiner Professor Sociology Yale University Date Defended/Approved: March 11, 2016 ii Abstract This dissertation features a comparative-historical examination of macrosocietal secularisation in France (1875-1905) and Turkey (1908-1938), with particular attention to their republican state building experiences. Bridging -

Catholic Clergy Sexual Abuse Meets the Civil Law Thomas P

Fordham Urban Law Journal Volume 31 | Number 2 Article 6 2004 Catholic Clergy Sexual Abuse Meets the Civil Law Thomas P. Doyle Catholic Priest Stephen C. Rubino Ross & Rubino LLP Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ulj Part of the Religion Law Commons Recommended Citation Thomas P. Doyle and Stephen C. Rubino, Catholic Clergy Sexual Abuse Meets the Civil Law, 31 Fordham Urb. L.J. 549 (2004). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ulj/vol31/iss2/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Urban Law Journal by an authorized editor of FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CATHOLIC CLERGY SEXUAL ABUSE MEETS THE CIVIL LAW Thomas P. Doyle, O.P., J.C.D.* and Stephen C. Rubino, Esq.** I. OVERVIEW OF THE PROBLEM In 1984, the Roman Catholic Church began to experience the complex and highly embarrassing problem of clergy sexual miscon- duct in the United States. Within months of the first public case emerging in Lafayette, Louisiana, it was clear that this problem was not geographically isolated, nor a minuscule exception.' In- stances of clergy sexual misconduct surfaced with increasing noto- riety. Bishops, the leaders of the United States Catholic dioceses, were caught off guard. They were unsure of how to deal with spe- cific cases, and appeared defensive when trying to control an ex- panding and uncontrollable problem. -

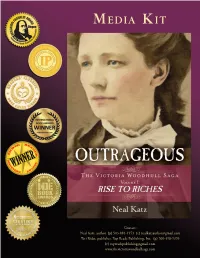

Mediately Draws You in with Believable Dialogue and a Subject Matter That Makes You Want to Know More

M EDIA KIT Contact: Neal Katz, author (p) 503-883-1973 (e) [email protected] Teri Rider, publisher, Top Reads Publishing, Inc. (p) 760-458-9393 (e) [email protected] www.thevictoriawoodhullsaga.com Complete listing of Awards Won – Outrageous, The Victoria Woodhull Saga, Volume 1: Rise to Riches (to date, April 16, 2017) Outrageous has won 9 major National Awards for Independent Publishing, and 1 International Award in a field of all published books. Individual awards listed below. IBPA Benjamin Franklin – Bill Fisher Award for Best First Book by a Publisher, Gold Medal http://iBpaBenjaminfranklinawards.com/2016-ibpa-bfa-finalists/#Bill1 Video interview: https://youtu.Be/2HQJ8tF1niI?list=PL0j72Ir-3hZEAu91MJ9lVwLYFuaPFPUZ4 Independent Publisher Book Awards, IPPY – Gold Medal for Best Historical Fiction http://www.independentpublisher.com/article.php?page=2045 Reader’s Favorite – Gold Medal for Best Historical Fiction / Personage https://readersfavorite.com/book-review/outrageous International Book Awards – Winner, Best New Fiction http://www.internationalbookawards.com/2016awardannouncement.html Indie Reader Discovery Award – Second Place Winner in Fiction http://indiereader.com/indiereader-discovery-awards/past-winners/ Next Generation Indie Book Award – Finalist Historical Fiction http://www.indieBookawards.com/winners/2016 Independent Author Network (IAN) Book of the Year Awards – Finalist in Two Categories: Historical Fiction, First Novel http://www.independentauthornetwork.com/2016-book-of-the-year-winners.html Chanticleer -

Clericalism: Enabler of Clergy Sexual Abuse

Pastoral Psychology, Vol. 54, No. 3, January 2006 (© 2006) DOI; 10.1007/S11089-006-6323-X Clericalism: Enabler of Clergy Sexual Abuse Thomas P. Doyle'^ Sexual abuse by Catholic clergy and religious has become the greatest challenge facing Catholicism since the Reformation. Violations of clerical celibacy have occurred throughout history. The institutional church remains defensive while scholars in the behavioral and social sciences probe deeply into the nature of institutional Catholicism, searching for meaningful explanations for the dysfunc- tional sexual behavior. Clericalism which has traditionally led to deep-seated societal attitudes about the role of the clergy in religious and secular society, explains in part why widespread abuse has apparently been allowed. Clericalism has a profound emotional and psychological influence on victims, church lead- ership, and secular society. It has enabled the psychological duress experienced by victims which explains why many have remained silent for years. It has also inspired societal denial which has impeded many from accepting clergy sexual abuse as a serious and even horrific crime. KEY WORDS: clericalism; Roman Catholic Church; clergy sexual abuse; narcissism. To fully understand both the origins and the complex impact of the contem- porary clergy sexual abuse scandal, one must understand some of the more subtle yet powerful inner workings of institutionalized Catholicism. Above all, one must appreciate the nature of clericalism and the impact it has had on Catholic life in general but especially on the victims of clergy sexual abuse. Catholicism is a spiritual force, a way of life, and a religious movement. It is also a complex socio-cultural reality and a world-wide political entity.