The Spatial Economy of Dharavi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bandra Kurla Complex Routes (Air Conditioned)

Bandra Kurla Complex Routes (Air Conditioned) SR Route From Trip Times To Trip Times NO No. ITINERARY DHARAVI DEPOT to 6.35 6.50 BORIVALI STN (E) to BKC 7.30 7.45 BKC-DIAMOND MRKT-MMRDA-KALANAGAR-VAKOLA-HANUMAN BORIVALI STN (E) 7.05 7.20 8.00 8.15 ROAD-GUNDHAVLI-GOREGAON -PUSPA PARK-MAGATHANE- 7.35 8.30 BORIVALI STN (E) 1 BKC-10 BKC to BORIVALI STN(E) 18.00 18.15 BORIVALI STN (E) to DHARAVI 19.40 19.55 18.30 18.45 DEPOT 20.10 20.25 19.00 20.40 DHARAVI DEPOT to 6.25 6.35 HIRANANDANI ( THANE) to 7.30 7.45 MMRDA-BHARAT NAGAR-DIAMoND MRKT-GODREJ CO.-BHANDUP BKC-11 HIRANANDANI ( THANE) 6.50 7.00 B.K.C 8.00 8.15 PUMPING CENTER-LOUIS WADI-MAJIWADA-MANPADA-PATLI PADA 2 B.K.C to HIRANANDANI 18.00 18.20 HIRANANDANI ( THANE) to 19.40 20.00 HIRANANDANI ESTATE (THANE) 18.40 19.00 DHARAVI DEPOT 20.20 20.40 DHARAVI DEPOT to 6.25 6.40 JALVAYU VIHAR,KHARGHAR 7.30 7.45 MMRDA-BHARAT NAGAR-Diamond MRKT-CHHEDA NAGAR-TURBHE BKC-12 JALVAYU VIHAR,KHARGHAR 6.50 7.00 TO B.K.C 8.00 8.15 POLICE STN-URAN PHATA-SHILP CHK-JALVAYU VIHAR 3 B.K.C to JAL VAYU VIHAR, 18.00 18.20 JALVAYU VIHAR,KHARGHAR 19.40 20.00 KHARGHAR 18.40 19.00 to DHARAVI DEPOT 20.20 20.40 DHARAVI DEPOT to 6.25 6.35 M.P.CHOWK,MULUND to 7.30 7.45 BKC- INCOME TAX OFFICE-BHARAT NAGAR-Diamond MRKT- BKC-13 M.P.CHOWK,MULUND 6.50 7.00 B.K.C 8.00 8.15 KURLA DEPOT-SARVODAYA HOSP.-GANDHI NAGAR-BHANDUP STN(W)- 4 B.K.C to M.P.CHOWK,MULUND 18.00 18.20 M.P.CHOWK,MULUND to 19.40 20.00 M.P.CHOWK(MULUND) 18.40 19.00 DHARAVI DEPOT 20.20 20.40 SR Route First Last First Last From To Frequency NO No. -

CRAMPED for ROOM Mumbai’S Land Woes

CRAMPED FOR ROOM Mumbai’s land woes A PICTURE OF CONGESTION I n T h i s I s s u e The Brabourne Stadium, and in the background the Ambassador About a City Hotel, seen from atop the Hilton 2 Towers at Nariman Point. The story of Mumbai, its journey from seven sparsely inhabited islands to a thriving urban metropolis home to 14 million people, traced over a thousand years. Land Reclamation – Modes & Methods 12 A description of the various reclamation techniques COVER PAGE currently in use. Land Mafia In the absence of open maidans 16 in which to play, gully cricket Why land in Mumbai is more expensive than anywhere SUMAN SAURABH seems to have become Mumbai’s in the world. favourite sport. The Way Out 20 Where Mumbai is headed, a pointer to the future. PHOTOGRAPHS BY ARTICLES AND DESIGN BY AKSHAY VIJ THE GATEWAY OF INDIA, AND IN THE BACKGROUND BOMBAY PORT. About a City THE STORY OF MUMBAI Seven islands. Septuplets - seven unborn babies, waddling in a womb. A womb that we know more ordinarily as the Arabian Sea. Tied by a thin vestige of earth and rock – an umbilical cord of sorts – to the motherland. A kind mother. A cruel mother. A mother that has indulged as much as it has denied. A mother that has typically left the identity of the father in doubt. Like a whore. To speak of fathers who have fought for the right to sire: with each new pretender has come a new name. The babies have juggled many monikers, reflected in the schizophrenia the city seems to suffer from. -

Hotel List 19.03.21.Xlsx

QUARANTINE FACILITIES AVAILABLE AS BELOW (Rate inclusive of Taxes and Three Meals) NO. DISTRICT CATEGORY NAME OF THE HOTEL ADDRESS SINGLE DOUBLE VACANCY POC CONTACT NUMBER FIVE STAR HOTELS 1 Mumbai Suburban 5 Star Hilton Andheri (East) 3449 3949 171 Sandesh 9833741347 2 Mumbai Suburban 5 Star ITC Maratha Andheri (East) 3449 3949 70 Udey Schinde 9819515158 3 Mumbai Suburban 5 Star Hyatt Regency Andheri (East) 3499 3999 300 Prashant Khanna 9920258787 4 Mumbai Suburban 5 Star Waterstones Hotel Andheri (East) 3500 4000 25 Hanosh 9867505283 5 Mumbai Suburban 5 Star Renaissance Powai 3600 3600 180 Duty Manager 9930863463 6 Mumbai Surburban 5 Star The Orchid Vile Parle (East) 3699 4250 92 Sunita 9169166789 7 Mumbai Suburban 5 Star Sun-N- Sand Juhu, Mumbai 3700 4200 50 Kumar 9930220932 8 Mumbai Suburban 5 Star The Lalit Andheri (East) 3750 4000 156 Vaibhav 9987603147 9 Mumbai Surburban 5 Star The Park Mumbai Juhu Juhu tara Rd. Juhu 3800 4300 26 Rushikesh Kakad 8976352959 10 Mumbai Suburban 5 Star Sofitel Mumbai BKC BKC 3899 4299 256 Nithin 9167391122 11 Mumbai City 5 Star ITC Grand Central Parel 3900 4400 70 Udey Schinde 9819515158 12 Mumbai Suburban 5 Star Svenska Design Hotels SAB TV Rd. Andheri West 3999 4499 20 Sandesh More 9167707031 13 Mumbai Suburban 5 Star Meluha The Fern Hiranandani Powai 4000 5000 70 Duty Manager 9664413290 14 Mumbai Suburban 5 Star Grand Hyatt Santacruz East 4000 4500 120 Sonale 8657443495 15 Mumbai City 5 Star Taj Mahal Palace (Tower) Colaba 4000 4500 81 Shaheen 9769863430 16 Mumbai City 5 Star President, Mumbai Colaba -

The Development of Kalyan Dombivili; Fringe City in a Metropolitan Region

CITY REPORT 2 JULY 2013 The Development of Kalyan Dombivili; Fringe City in a Metropolitan Region By Isa Baud, Karin Pfeffer, Tara van Dijk, Neeraj Mishra, Christine Richter, Berenice Bon, N. Sridharan, Vidya Sagar Pancholi and Tara Saharan 1.0. General Introduction: Framing the Context . 3 Table of Contents 8. Introduction: Context of Urban Governance in the City Concerned . 3 1. Introduction: Context of Urban Governance in the City Concerned . 3 1.1. Levels of Government and Territorial Jurisdictions in the City Region . 7 1.0. General Introduction: Framing the Context . 3 1.1. Levels of Government and Territorial Jurisdictions Involved in the City Region: National/Sectoral, Macro-Regional (Territory), Metropolitan, Provincial and Districts . 7 9. Urban Growth Strategies – The Role of Mega-Projects . 10 2. Urban Growth Strategies – The Role of Mega-Projects . 10 2.1. KDMC’s Urban Economy and City Vision: 2.1. KDMC’s Urban Economy and City Vision: Fringe City in the Mumbai Agglomeration . 10 Fringe City in the Mumbai Agglomeration . 10 3.1. Urban Formations; 3. Addressing Urban Inequality: Focus on Sub-Standard Settlements . 15 Socio-Spatial Segregation, Housing and Settlement Policies . 15 3.1. Urban Formations; Socio-Spatial Segregation, Implications for Housing and Settlement Policies . 15 3.2. Social Mobilization and Participation . 20 10. Addressing Urban Inequality: . 15 3.3. Anti-Poverty Programmes in Kalyan Dombivili . 22 11. Focus on Sub-Standard Settlements9 . 15 4. Water Governance and Water-Related Vulnerabilities . 26 4.1. Water Governance . 26 3.2. Social Mobilization and Participation . 20 4.2. Producing Spatial Analyses of Water-Related Risks and Vulnerabilities: 3.3. -

Redharavi1.Pdf

Acknowledgements This document has emerged from a partnership of disparate groups of concerned individuals and organizations who have been engaged with the issue of exploring sustainable housing solutions in the city of Mumbai. The Kamala Raheja Vidyanidhi Institute of Architecture (KRVIA), which has compiled this document, contributed its professional expertise to a collaborative endeavour with Society for Promotion of Area Resource Centres (SPARC), an NGO involved with urban poverty. The discussion is an attempt to create a new language of sustainable urbanism and architecture for this metropolis. Thanks to the Dharavi Redevelopment Project (DRP) authorities for sharing all the drawings and information related to Dharavi. This project has been actively guided and supported by members of the National Slum Dwellers Federation (NSDF) and Dharavi Bachao Andolan: especially Jockin, John, Anand, Savita, Anjali, Raju Korde and residents’ associations who helped with on-site documentation and data collection, and also participated in the design process by giving regular inputs. The project has evolved in stages during which different teams of researchers have contributed. Researchers and professionals of KRVIA’s Design Cell who worked on the Dharavi Redevelopment Project were Deepti Talpade, Ninad Pandit and Namrata Kapoor, in the first phase; Aditya Sawant and Namrata Rao in the second phase; and Sujay Kumarji, Kairavi Dua and Bindi Vasavada in the third phase. Thanks to all of them. We express our gratitude to Sweden’s Royal University College of Fine Arts, Stockholm, (DHARAVI: Documenting Informalities ) and Kalpana Sharma (Rediscovering Dharavi ) as also Sundar Burra and Shirish Patel for permitting the use of their writings. -

Affiliated Club List

GONDWANA CLUB, NAGPUR RECIPROCAL ARRANGEMENT BETWEEN THE FOLLOWING CLUBS S.No Name of the Club Address STD Code Telephone No. Fax No. Email address & Web site 1 The Roshanara Club Roshanara Gardens,Delhi-07. 11 65182201/02 23843094 [email protected] 65182232 www.roshanaraclub.com 2 Jahanpanah Club Mandakini Housing Scheme 11 26277072/73/74 26272691 [email protected] Alaknanda, New Delhi-19. 3 Riverside Sports & Club Avenue, Mayur Vihar 11 22714765, 22711986 [email protected] Recreation Club PH-I, Extn., Delhi -110091 22711857 www.riversideclub.in 4 Malabar Hill Club Ltd. B.G.Kher Marg, Malabar 22 23631636 23628693 [email protected] hills, Mumbai - 06. 23633350 22833213 www.malabarhillclub.com 23634055 5 The Bombay Presidency Radio 157, Arthur Bunder Road 22 22845025/71/75 22833213 [email protected] Club Ltd. Colaba, Bombay-20 22845121/23 6 MIG Cricket Club MIG Colony, Bandra(E) 22 26408899/26436594 26436593 [email protected] Mumbai-51. 26457108/09 www.migcricketclub.org 26407333/6907/6909 7 Juhu Vile Parle Gymkhana N.S.Road No. 13, JVPD Scheme 22 26206016/ 26205937 26209702 [email protected] Club Opp. Juhu Bus Station, Juhu, 26205973 [email protected] Mumbai - 400049. 8 Bombay Gymkhana Ltd. Mahatma Gandhi Road 22 22070311/12/13/14 22070431 [email protected] Fort, Mumbai - 400001 22070760/63/66/68 22071401 www.bombaygymkhana.com 9 The Calcutta Swimming Club 1, Strand Road,Calcutta-01. 33 22482837/94/95 22420854 [email protected] www.calcuttaswimmingclub.com 10 Tollygunge Club Ltd. 120, Deshapran Sasmal Road 33 2473-4539/5954 24720480 [email protected] Kolkata-33. (West Bengal) 2473-4741/2316 24731903 [email protected] www.tollygungeclub.org 11 The Saturday Club Limited. -

MUMBAI | OFFICE 31 July 2018

Colliers Quarterly Q2 2018 MUMBAI | OFFICE 31 July 2018 BFSI to be key driver for demand Growing demand Mumbai recorded gross absorption of 1.7 million sq ft (0.16 million sq m) in Q2 2018 taking the total for H1 2018 to 3.7 million sq ft (0.34 million sq m). This momentum represents a 27% increase from H1 2017. In Q2 2018, leasing activity was concentrated in the micromarkets of Diksha Gulati Manager | Mumbai Andheri East and Bandra-Kurla Complex (BKC), with shares of 38% and 14% respectively. Demand continued Mumbai continued to witness growing momentum in to be driven by flexible workspace operators which took leasing and outright purchase of office space for a 20% share, followed by BFSI with a 16% share and self-use by occupiers in the Banking and Financial then the IT-ITeS, consulting and logistics sectors. The Services Institutions (BFSI), logistics and preferred micromarkets for flexible workspace operators manufacturing sectors. For premium front-office were Andheri East, BKC, Navi Mumbai and space, BFSI occupiers should focus on Bandra Kurla Worli/Prabhadevi. Complex (BKC), while cost-sensitive occupiers should evaluate options in micromarkets such as Mumbai witnessed significant outright purchases for self- Lower Parel and Andheri. use in H1 2018 by occupiers in varied sectors including BFSI, logistics and manufacturing. Notable transactions Forecast at a glance included occupiers acquiring 30,000-60,000 sq ft (2,788- Demand 5,576 sq m) office space in Andheri and Navi Mumbai. We expect demand to increase owing to Robust absorption by the BFSI sector is likely to be the consolidation in Mumbai's traditional key driver for leasing activity in H2 2018 as a number of demand driver BFSI companies in the BFSI sector are looking at Supply consolidating their office space. -

Designation Name of the Officer Office Tel.No. Fax No Location EPBX No

TELEPHONE DIRECTORY FOR MUMBAI REGION PRINCIPAL CHIEF COMMISSIONER OF INCOME TAX ROOM NO. 321, AAYAKAR BHAVAN, M.K. ROAD, MUMBAI-400020 Designation Name of the officer Office Tel.No. Fax No location EPBX No Staff room Pr.CCIT Patanjali 22017654 22062597 AB-321 2322 373 CIT(Admn & TPS) Rajesh Damor 22120261 22120262 AB-324 2324 133 A.O. to Pr.CCIT Pramod Y Devikar AB-373 2373 373 Sr.P.S. Deepa Rasal 22017654 22062597 AB-322 2322/2182 322 PS Vinita Bipin 22017654 22062597 AB-322 2322/2182 322 ADDITIONAL COMMISSIONERS OF INCOME TAX WITH PR.CCIT Designation Name of the officer Office Tel.No. Fax No location EPBX No Staff room Addl.CIT(HQ) Admin, Vig & Tech Abhinay Kumbhar 22014373 22095481 AB-329 2329 326+316 Addl CIT(HQ) Project & TPS Arju Garodia 22129210 22120235 AB-337 2337 111 Addl .CIT(HQ) Co-ordination Sambit Mishra 22014596 22013301 AB-335 2335 111 Addl.CIT(HQ) Personnel Dhule Kishore Sakharam 22016691 22079273 AB-340 2340 383 COMMISSIONER OF INCOME TAX (ADMIN. & TPS) R.NO.324, 3RD FLOOR, AAYAKAR BHAVAN, M.K. ROAD MUMBAI - 400 020. Designation Name of the officer Office Tel.No. FAX NO location EPBX No. Staff room CIT (Admn. & TPS) Rajesh Damor 22120261 22120262 AB-324 2324 133C Jt./Addl. CIT (CO) K P R R Murty 26570003 26570003 139A DCIT (CO) Ashok Natha Bhalekar 22078288 133C J.D. (Systems) S. Renganathan AB 120 133C D.D. (Systems) Rajesh Kumar 26570426 AB 114 133C A.D. (Systems)-1 Sajeev Sathyadasan 26572622 AB 115 133C A.D. -

Heritage List

LISTING GRADING OF HERITAGE BUILDINGS PRECINCTS IN MUMBAI Task II: Review of Sr. No. 317-632 of Heritage Regulation Sr. No. Name of Monuments, Value State of Buildings, Precincts Classification Preservation Typology Location Ownership Usage Special Features Date Existing Grade Proposed Grade Photograph 317Zaoba House Building Jagananth Private Residential Not applicable as the Not applicable as Not applicable as Not applicable as Deleted Deleted Shankersheth Marg, original building has been the original the original the original Kalbadevi demoilshed and is being building has been building has been building has been rebuilt. demoilshed and is demoilshed and is demoilshed and is being rebuilt. being rebuilt. being rebuilt. 318Zaoba Ram Mandir Building Jagananth Trust Religious Vernacular temple 1910 A(arc), B(des), Good III III Shankersheth Marg, architecture.Part of building A(cul), C(seh) Kalbadevi in stone.Balconies and staircases at the upper level in timber. Decorative features & Stucco carvings 319 Zaoba Wadi Precinct Precinct Along Jagannath Private Mixed Most features already Late 19th century Not applicable as Poor Deleted Deleted Shankershet Marg , (Residential & altered, except buildings and early 20th the precinct has Kalbadevi Commercial) along J. S. Marg century lost its architectural and urban merit 320 Nagindas Mansion Building At the intersection Private (Nagindas Mixed Indo Edwardian hybrid style 19th Century A(arc), B(des), Fair II A III of Dadasaheb Purushottam Patel) (Residential & with vernacular features like B(per), E, G(grp) Bhadkamkar Marg Commercial) balconies combined with & Jagannath Art Deco design elements Shankersheth & Neo Classical stucco Road, Girgaum work 321Jama Masjid Building Janjikar Street, Trust Religious Built on a natural water 1802 A(arc), A(cul), Good II A II A Near Sheikh Menon (Jama Masjid of (Muslim) source, displays Islamic B(per), B(des),E, Street Bombay Trust) architectural style. -

Colaba- Bandra-SEEPZ Metro 3 Corridor

Colaba- Bandra-SEEPZ Metro 3 Corridor Mumbai Metro Rail Corporation signs agreement with ALSTOM for Rolling Stock Alstom will supply 248 metro cars for Metro Line 3 Mumbai, September 10, 2018: Mumbai Metro Rail Corporation Limited (MMRC) today signed agreement for procurement of state-of-the-art Rolling Stock with “Consortium of ALSTOM Transport India Ltd and ALSTOM Transport S.A. France” for Colaba-Bandra-SEEPZ Metro-3 corridor. Being the most competitive amongst the respective pre-qualified bidders, the contract to ALSTOM was awarded on July 19, 2018. The scope of work for M/s.Alstom is to Design, Manufacture, Supply, Install, Test and Commission 31 trains with 8 cars (width of 3.2m) configuration. The train will be of approximately 180m, with 2350 passenger carrying capacity (estimated at 6 passengers per square metre) and about 300 passengers carrying capacity for each coach with having longitudinal seating arrangement. The trains will operate on 25 KV AC Traction supply. The stainless steel cars will have 4 doors on each side. Commenting on the same, Spokesperson of MMRC said, “This is an important step towards fruition of a mega project that will certainly put Mumbaikars at comfort and great safety". Alain SPOHR, Managing Director, Alstom India and South Aisa said, "We are delighted to be the partner of choice for the prestigious Mumbai Metro Line 3 project. By providing reliable, advanced and competitive transportation solutions, we are committed bro support our customer in easing Mumbai's transport challenges. With the stipulating 75% manufacturing in India, this contract has further reinforced our commitment to invest, grow and Make In India. -

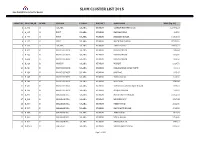

List of Slum Cluster 2015

SLUM CLUSTER LIST 2015 Slum Rehabilitation Authority, Mumbai OBJECTID CLUSTER_ID WARD VILLAGE TALUKA DISTRICT SLUM NAME AREA (Sq. M.) 1 A_001 A COLABA COLABA MUMBAI GANESH MURTHI NAGAR 120771.23 2 A_005 A FORT COLABA MUMBAI BANGALIPURA 318.50 3 A_006 A FORT COLABA MUMBAI NARIMAN NAGAR 14315.98 4 A_007 A FORT COLABA MUMBAI MACHIMAR NAGAR 37181.09 5 A_009 A COLABA COLABA MUMBAI GEETA NAGAR 26501.21 6 B_021 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI DANA BANDAR 939.53 7 B_022 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI DANA BANDAR 1292.90 8 B_023 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI DANA BANDAR 318.67 9 B_029 B MANDVI COLABA MUMBAI MANDVI 1324.71 10 B_034 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI NALABANDAR JOPAD PATTI 600.14 11 B_039 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI JHOPDAS 908.47 12 B_045 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI INDRA NAGAR 1026.09 13 B_046 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI MAZGAON 1541.46 14 B_047 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI SUBHASHCHANDRA BOSE NAGAR 848.16 15 B_049 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI MASJID BANDAR 277.27 16 D_001 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI MATA PARVATI NAGAR 21352.02 17 D_003 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI BRANHDHARY 1597.88 18 D_006 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI PREM NAGAR 3211.09 19 D_007 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI NAVSHANTI NAGAR 4013.82 20 D_008 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI ASHA NAGAR 1899.04 21 D_009 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI SIMLA NAGAR 9706.69 22 D_010 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI SHIVAJI NAGAR 1841.12 23 D_015A D GIRGAUM COLABA MUMBAI SIDHDHARTH NAGAR 2189.50 Page 1 of 101 SLUM CLUSTER LIST 2015 Slum Rehabilitation Authority, Mumbai OBJECTID CLUSTER_ID WARD VILLAGE TALUKA DISTRICT SLUM NAME AREA (Sq. -

Axis Bank Ltd. 131, Maker Towers 'F', Cuffe Parade, Colaba Mumbai - 400005 Tel

Axis Bank Ltd. 131, Maker Towers 'F', Cuffe Parade, Colaba Mumbai - 400005 Tel. 6707 4407 PRESS RELEASE AXIS BANK ANNOUNCES Q3 NET PROFIT AT Rs. 306.83 CRORES; UP BY 66.20% YOY NINE MONTHS NET PROFIT AT Rs. 709.63 CRORES ; UP BY 58.70% YOY Axis Bank has announced its unaudited results for Q3 2007-08 and for the nine months ended December 2007, following the approval of its Board of Directors in a meeting held in Mumbai on 9th January, 2008. The Net Profit for the third quarter was Rs. 306.83 crores, up by 66.20% over the Net Profit of Rs. 184.61 crores for the third quarter of last year. The Net Profit of the Bank for the nine months ended December 2007 was Rs. 709.63 crores, up by 58.70% over the Net Profit of Rs. 447.14 crores during the first nine months of the previous year. RESULTS AT A GLANCE: Q3 FY 2007-08 9M FY 2007-08 Net Profit :Rs. 306.83 crores ↑ 66.20% YOY Rs. 709.63 crores ↑ 58.70% YOY Net Interest Income :Rs. 747.34 crores ↑ 91.12% YOY Rs. 1,756.92 crores↑ 70.68% YOY Fee Income : Rs. 348.41 crores ↑ 80.91% YOY Rs. 905.38 crores ↑ 70.67% YOY Net Interest Margin : 3.91%* ↑ from 3.00% 3.28%* ↑ from 2.87% Cost of Funds : 5.72% ↑ from 5.53% 6.10% ↑ from 5.47% Demand Deposits :Rs. 31,032 crores ↑ 64.34 % YOY Capital Adequacy Ratio: 16.88% ↑ from 11.83% *Adjusted for amortisation RESULTS FOR Q3 FY 07-08: The Net Interest Income for Q3 was Rs.