Changing Stereotypes in Iran and Canada Using Computer Mediated Communicatione Sida 1 Av 15

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CIC Diversity Colume 6:2 Spring 2008

VOLUME 6:2 SPRING 2008 Guest Editor The Experiences of Audrey Kobayashi, Second Generation Queen’s University Canadians Support was also provided by the Multiculturalism and Human Rights Program at Canadian Heritage. Spring / printemps 2008 Vol. 6, No. 2 3 INTRODUCTION 69 Perceived Discrimination by Children of A Research and Policy Agenda for Immigrant Parents: Responses and Resiliency Second Generation Canadians N. Arthur, A. Chaves, D. Este, J. Frideres and N. Hrycak Audrey Kobayashi 75 Imagining Canada, Negotiating Belonging: 7 Who Is the Second Generation? Understanding the Experiences of Racism of A Description of their Ethnic Origins Second Generation Canadians of Colour and Visible Minority Composition by Age Meghan Brooks Lorna Jantzen 79 Parents and Teens in Immigrant Families: 13 Divergent Pathways to Mobility and Assimilation Cultural Influences and Material Pressures in the New Second Generation Vappu Tyyskä Min Zhou and Jennifer Lee 84 Visualizing Canada, Identity and Belonging 17 The Second Generation in Europe among Second Generation Youth in Winnipeg Maurice Crul Lori Wilkinson 20 Variations in Socioeconomic Outcomes of Second Generation Young Adults 87 Second Generation Youth in Toronto Are Monica Boyd We All Multicultural? Mehrunnisa Ali 25 The Rise of the Unmeltable Canadians? Ethnic and National Belonging in Canada’s 90 On the Edges of the Mosaic Second Generation Michele Byers and Evangelia Tastsoglou Jack Jedwab 94 Friendship as Respect among Second 35 Bridging the Common Divide: The Importance Generation Youth of Both “Cohesion” and “Inclusion” Yvonne Hébert and Ernie Alama Mark McDonald and Carsten Quell 99 The Experience of the Second Generation of 39 Defining the “Best” Analytical Framework Haitian Origin in Quebec for Immigrant Families in Canada Maryse Potvin Anupriya Sethi 104 Creating a Genuine Islam: Second Generation 42 Who Lives at Home? Ethnic Variations among Muslims Growing Up in Canada Second Generation Young Adults Rubina Ramji Monica Boyd and Stella Y. -

Exploring the Iranian-Canadian Family Experience of Dementia Caregiving: a Phenomenological Study

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 7-19-2013 12:00 AM Exploring the Iranian-Canadian Family Experience of Dementia Caregiving: A Phenomenological Study Sevil Deljavan The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Sandra Hobson The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Health and Rehabilitation Sciences A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Science © Sevil Deljavan 2013 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Mental and Social Health Commons, and the Nervous System Diseases Commons Recommended Citation Deljavan, Sevil, "Exploring the Iranian-Canadian Family Experience of Dementia Caregiving: A Phenomenological Study" (2013). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 1590. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/1590 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EXPLORING THE IRANIAN-CANADIAN FAMILY EXPERIENCE OF DEMENTIA CAREGIVING: A PHENOMENOLOGICAL STUDY (Thesis Format: Monograph) by Sevil Deljavan Graduate Program in Health and Rehabilitation Sciences A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Science The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Sevil Deljavan 2013 Abstract Presently in Canada, there are approximately 500,000 individuals living with dementia, which is expected to increase to over one million by 2038. With Canada’s minority elderly population growing, the number of Iranian-Canadian older adults living with dementia is expected to rise as well. -

TWO CANADIANS MEET in SPACE Julie Payette

September 2009 News in Review Resource Guide September 2009 Credits Resource Guide Writers: Diane Ballantyne, Sean Dolan, Peter Flaherty, Jim L’Abbé Copy Editor and Desktop Publisher: Susan Rosenthal Resource Guide Graphics: Laraine Bone Production Assistant: Carolyn McCarthy Resource Guide Editor: Jill Colyer Supervising Manager: Karen Bower Host: Carla Robinson Senior Producer: Nigel Gibson Producer: Lou Kovacs Video Writers: Nigel Gibson Director: Ian Cooper Graphic Artist: Mark W. Harvey Editor: Stanley Iwanski Visit us at our Web site at our Web site at http://newsinreview.cbclearning.ca, where you will find News in Review indexes and an electronic version of this resource guide. As a companion resource, we recommend that students and teachers access CBC News Online, a multimedia current news source that is found on the CBC’s home page at http://cbcnews.cbc.ca. Close-captioning News in Review programs are close-captioned. Subscribers may wish to obtain decoders and “open” these captions for the hearing impaired, for English as a Second Language students, or for situations in which the additional on-screen print component will enhance learning. CBC Learning authorizes the reproduction of material contained in this resource guide for educational purposes. Please identify the source. News in Review is distributed by CBC Learning, P.O. Box 500, Station A, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M5W 1E6 Tel: (416) 205-6384 • Fax: (416) 205-2376 • E-mail: [email protected] Copyright © 2009 Canadian Broadcasting Corporation News in Review, September 2009 1. Two Canadians Meet in Space (Length: 15:22) 2. Canada and the Swine Flu (Length: 14:54) 3. -

Iran's Human Rights Violators and Canada's Magnitsky Statutes

Briefing Book, January 2020 Iran’s Human Rights Violators and Canada’s Magnitsky Statutes A Canadian Primer The Canadian Coalition Against Terror (C-CAT) is a policy, research and advocacy group committed to developing innovative strategies in the battle against extremism and terrorism. C-CAT is comprised of terror victims, counterterrorism professionals, lawyers and others dedicated to building bridges between the private and public sectors in this effort. http://www.c-catcanada.org The contents of this briefing binder may be reproduced in whole or part with proper attribution to the original source(s) Dr. Ahmed Shaheed: (UN special rapporteur on freedom of religion or belief from 2011 to 2016) “Those who violate human rights in Iran are not fringe or renegade officials. Rather, they hold senior positions in the executive branch and the judiciary, where they continue to enjoy impunity. These officials control a vast infrastructure of repression that permeates the lives of Iranian citizens. …Defiance of these norms often comes at a terrible cost, with Iranians frequently facing unjust detention, torture, and even death.”1 Table of Contents 1. A Memo to the Reader---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------1 2. Canada-Iran Overview---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------3 > Canada-Iran-Relations Fact Sheet > Iran’s International Ranking as a Human Rights Violator > Iran’s International Ranking for Corruption 3. The Magnitsky Act and Iran --------------------------------------------------------------------------------8 -

Iran in the World: the Nuclear Crisis in Context

Iran in the World: The Nuclear Crisis in Context Edited by Soushiant Zanganehpour and Wade L. Huntley Simons Centre for Disarmament and Non-Proliferation Research, a unit of the Liu Institute for Global Issues Vancouver, BC, Canada Iran in the World: The Nuclear Crisis in Context Edited by Soushiant Zanganehpour and Wade L. Huntley © 2008: The Simons Centre for Disarmament and Non-Proliferation Research (4) All rights reserved. Small excerpts of this publication may be reproduced, downloaded, disseminated and transferred for academic/scholarly purposes without permission as long as express attribution is given to the publication source and to the Simons Centre for Disarmament and Non-proliferation Research at the University of British Columbia as publisher. Reproduction, storage or transmission of substantial portions of this publication requires the prior written permission of the Simons Centre. The unaltered complete electronic (PDF) version of the publication may be freely copied and disseminated without prior notification. Simons Centre for Disarmament and Non-Proliferation Research Liu Institute for Global Issues, University of British Columbia 6476 NW Marine Drive Vancouver, BC V6T 1Z2 Canada Tel: 604-822-0552 Fax: 604-822-6966 Email: [email protected] Website: www.ligi.ubc.ca Cover design by Industry Images, Vancouver Acknowledgements This publication presents the revised contributions to the namesake conference convened by the Simons Centre for Disarmament and Non- Proliferation Research in Vancouver on 11-13 March 2007. The conference and the publication were made possible by the financial and logistical support of the International Security Research and Outreach Programme (ISROP) of the Canadian Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade (DFAIT), the Security and Defense Forum (SDF) of the Canadian Department of National Defense, and the Liu Institute for Global Issues at the University of British Columbia. -

Citizenship Revocation in the Mainstream Press: a Case of Re-Ethni- Cization?

CITIZENSHIP REVOCATION IN THE MAINSTREAM PRESS: A CASE OF RE-ETHNI- CIZATION? ELKE WINTER IVANA PREVISIC Abstract. Under the original version of the Strengthening Canadian Citizenship Act (2014), dual citizens having committed high treason, terrorism or espionage could lose their Canadian citizenship. In this paper, we examine how the measure was dis- cussed in Canada’s mainstream newspapers. We ask: who/what is seen as the target of citizenship revocation? What does this tell us about the direction that Canadian citizenship is moving towards? Our findings show that Canadian newspapers were more often critical than supportive of the citizenship revocation provision. However, the press ignored the involvement of non-Muslim, white, Western-origin Canadians in terrorist acts and interpreted the measure as one that was mostly affecting Canadian Muslims. Thus, despite advocating for equal citizenship in principle, in their writing and reporting practice, Canadian newspapers constructed Canadian Muslims as sus- picious and less Canadian nonetheless. Keywords: Muslim Canadians; Citizenship; Terrorism; Canada; Revocation Résumé: Au sein de la version originale de la Loi renforçant la citoyenneté cana- dienne (2014), les citoyens canadiens ayant une double citoyenneté et ayant été condamnés pour haute trahison, pour terrorisme ou pour espionnage, auraient pu se faire révoquer leur citoyenneté canadienne. Dans cet article, nous étudions comment ce projet de loi fut discuté au sein de la presse canadienne. Nous cherchons à répondre à deux questions: Qui/quoi est perçu comme pouvant faire l’objet d’une révocation de citoyenneté? En quoi cela nous informe-t-il sur les orientations futures de la citoy- enneté canadienne? Nos résultats démontrent que les journaux canadiens sont plus critiques à l’égard de la révocation de la citoyenneté que positionnés en sa faveur. -

The Impact of Acculturation and Biculturalism on The

THE IMPACT OF ACCULTURATION AND BICULTURALISM ON THE SECOND GENERATIONS LIVING IN CANADA By Shakiba Ahani A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Counselling (MC) City University of Seattle Vancouver BC, Canada site March 15, 2016 APPROVED BY Larry Green, Ph.D., R.C.C. Thesis Supervisor, Counselling Psychology Faculty Chris Kinman, M.Sc. & M.Div. Counselling Psychology Faculty Division of Arts and Sciences 1 Abstract The present study explores the experience of second generation Canadian youth in terms of acculturation and possible negative psychological impacts. Stressors that are associated with second generation Canadian youth have been identified as acculturation, biculturalism, cultural conflict within relationships, being a visible minority, and discrimination. This study utilizes a narrative literature review methodology to explore the challenges faced by second generation Canadian youth. Through this literature review I was able to describe, examine, and evaluate research looking at stressors unique to second generation Canadian youth in order to provide a better understanding for counsellors. Findings from this literature review indicated that second generation Canadian youth, compared to other Canadian youth, are experiencing additional stressors that negatively impact mental health and overall well-being. Themes that emerged from this review include: the important role of family, peers and factors associated with the host society’s policies and attitude toward second generations. Marginalisation, discrimination, and lack of social support by the host society will create negative acculturation experience for second generation youth. However, acculturation pattern among second generation Canadian youth vary across ethnic groups and in order to avoid generalization more research is required to re-evaluate the story of second generation integration and closely examine day to day lived experiences of these generations in Canada. -

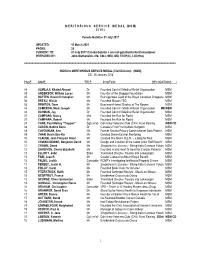

M E R I T O R I O U S S E R V I C E M E D a L (M S M) C I V I L Canada Gazettes 01 July 2017 UPDATED: 10 March 2021 PAGE

M E R I T O R I O U S S E R V I C E M E D A L (M S M) C I V I L Canada Gazettes 01 July 2017 UPDATED: 10 March 2021 PAGES: 28 CURRENT TO: 01 July 2017 Canada Gazette + one not gazetted to Kei Esmaeilpour PREPARED BY: John Blatherwick, CM, CStJ, OBC, MD, FRCP(C), LLD(Hon) =================================================================================================== INDEX to MERITORIOUS SERVICE MEDAL (Civil Division) (MSM) CG: 06 January 2018 PAGE NAME TITLE POSITION DECORATIONS / 04 ALMILAJI, Khaled Ahmad Dr Founded Cdn Int’l Medical Relief Organization MSM 05 ANDERSON, William Lucas Mr Founder of the Stopgap Foundation MSM 05 BATTEN, David Christopher Mr Reinvigorated Guild of the Royal Canadian Dragoons MSM 06 BREAU, Gisèle Ms Founded Maison TED MSM 06 BRINTON, Dean Mr Beaumont-Hamel Display at The Rooms MSM 04 CAMERON, Mark Joseph Mr Founded Cdn Int’l Medical Relief Organization MB MSM 04 DAHMAN, Jay Dr Founded Cdn Int’l Medical Relief Organization MSM 07 CAMPANA, Nancy Mrs Founded the Run for Rocky MSM 07 CAMPANA, Robert Mr Founded the Run for Rocky MSM 07 CANE, Paul Morley “Trapper” Sgt (ret’d) Cdn Army Veterans Club (CAV) Fund Raising MSM CD 08 CARON, Nadine Rena Dr Canada’s First First Nations Surgeon MSM 08 CAVOUKIAN, Ann Ms Former Ontario Privacy Commissioner Data Protect. MSM 09 CHAN, Kevin Sze-Kin Mr Created DreamCatcher Mentoring MSM 10 CLAUDE, Jean-François Omer Mr Created The Men’s D.E.N. – a Blog for Men MSM 10 COWAN-DEWAR, Benjamin David Mr Design and Creation of the Cabot Links Golf Resort MSM 11 CROWE, Derek Mr Singletrack to Success - Biking trails Carcross Yukon MSM 12 DAVIDSON, Cherie Elizabeth Ms Founded Island Heart to Heart for Cardiac Patients MSM 12 ELLIOTT, John Elder Translated Douglas Treaties into Lekwungen MSM 13 FABI, Jean R. -

Socio-Cultural Attitudes to Ta'arof Among Iranian

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Saskatchewan's Research Archive SOCIO-CULTURAL ATTITUDES TO TA’AROF AMONG IRANIAN IMMIGRANTS IN CANADA A thesis presented to the graduate faculty University of Saskatchewan in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Art by Gholamreza Haghighat Supervisor: Prof. Veronika Makarova “Copyright Gholamreza Haghighat, March, 2016, All Rights Reserved” PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Art from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of the University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purpose may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any materials in my thesis. Requests for permission to copy or to make other use of material in this thesis in whole or parts should be addressed to: Head of the Department of Linguistics and Religious Studies University of Saskatchewan Room 911, Arts Building 9 Campus Drive Saskatoon, SK S7N 5A5 Canada I DEDICATION To my lovely parents, siblings, brilliant daughter, Vania, and my supervisor, Prof. -

Iranian/Canadians: Homeland, Diaspora and Belonging Panel Discussion

THE CENTRE FOR CULTURE, IDENTITY & EDUCATION (CCIE) AND THE DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATIONAL STUDIES PRESENT: Iranian/Canadians: Homeland, Diaspora and Belonging Panel Discussion Wednesday, March 1st, 2017 2:00pm to 4:00pm Diaspora is a creative space for bringing out complexities of the extension of national cultures Ponderosa Commons Oak House and their emerging trends, for enhancing (PCOH) Room 2012 intercultural relations, and for extending the horizons of difference (e.g. via and beyond multiculturalism). In this panel, focusing on Iran, its diverse culture and education, and on Iranians in Canada, a group of Iranian scholars and educators inquire into the phenomenon of the Iranian diaspora. Exploring themes of diasporic life, exile and multicultural education, the panelists provide a grounding for opening up discussion around the perceptions, representations and transformations of culture and identities in the context of Iran and the Iranian diaspora. Encompassing several aspects of Iranian culture and life, the presenters cover a wide spectrum of subjects: from multicultural curriculum design in Iran to international Iranian students in Canada, from Iranian political culture to literary and visual arts representation of the Iranian diaspora. Photo by : Nasim Peikazadi Caspian Sea shore, Iran. ABSTRACTS Multicultural Education in Iran: Requirement, Challenges, and Solutions ALIREZA SADEGHI - Assistant Professor at Allameh Tabatabayi University and visiting scholar at the Centre for Culture, Identity & Education and Department of Educational Studies. The purpose of this presentation is an exploration in the features of multicultural education in Iran along with highlighting requirements, and challenges. This is followed by some suggestions for solutions. Now, people from, at least, thirteen (Iranian) ethnicities live together in Iran. -

Language Profile of Iranian Immigrants in Montréal Compared to Toronto

Language profile of Iranian immigrants in Montréal compared to Toronto Mémoire Simin Shafiefar Maîtrise en sociologie - avec mémoire Maître ès arts (M.A.) Québec, Canada © Simin Shafiefar, 2018 Language profile of Iranian immigrants in Montréal compared to Toronto Mémoire Simin Shafiefar Sous la direction de : Richard Marcoux, directeur de recherche RÉSUMÉ Comme le nombre d'immigrants Iraniens a augmenté au Canada au cours des dernières décennies, les nouvelles recherches sont nécessaires sur cette population. Étant donné que la transmission des langues immigrantes est une composante du processus d'établissement des immigrants et que les immigrants iraniens ont rarement fait l'objet d'études canadiennes, le but de cette recherche est d'étudier le profil linguistique des immigrants Iraniens à Montréal par rapport à Toronto. En utilisant les données du questionnaire long du recensement canadien de 2001, 2006 et 2011, nous avons étudié l'influence des facteurs sociodémographiques, familiaux et migratoires sur la langue que les immigrants Iraniens parlent le plus souvent à la maison à Montréal et à Toronto. Pour ce faire, nous avons procédé à différentes analyses descriptives pour déterminer si les immigrants Iraniens sont plus susceptibles de parler en langue non officielle (langue ancestrale) à la maison ou en langues officielles. Dans le but d'approfondir le profil linguistique des immigrants Iraniens à la maison, j'étends mes recherches en effectuant des régressions logistiques. Les résultats montrent que les immigrantes iraniennes par rapport à leurs homologues masculins, immigrants légalement mariés, les iraniens qui ont immigré au Canada à l'âge de 15 ans et plus ainsi que les immigrants iraniens arrivés au Canada après 1980 parlaient dans une langue non officielle à la maison plus que les langues officielles à Montréal ainsi qu’à Toronto. -

Mahmoud Khayami Elected Honorary Chair Ascicles of Olume F 1 & 2 V Xiii of the Eir

CENTER FOR IRANIAN STUDIES NEWSLETTER Vol. 17, No. 2 SIPA-Columbia University-New York Fall 2005 ENCYCLOPAEDIA IRANICA MAHMOUD KHAYAMI ELECTED HONORARY CHAIR ASCICLES OF OLUME F 1 & 2 V XIII OF THE EIR. BOARD PUBLISHED, FASCICLE 3 IN PRESS The first and second fascicles the West and Iranian Identity. A of Volume XIII of the Encyclopæ- review of these entries will be dia Iranica were published in the presented in the Spring 2006 issue Winter and Spring of 2005, and of the Newsletter. fascicle 3 is in press. The first two fascicles feature over 65 articles INDO-IRANIAN RELATIONS on various aspects of Persian culture and history, including four series of Indo-Iranian relations occupy most articles on specific subjects: 25 entries of the first fascicle of Volume XIII. It on Indo-Iranian relations, three entries would have taken much more space to on Investitures in pre-Islamic Iran, two fully cover, under this one heading, all entries on Inheritance in the Sasanian the areas in which Iranians and Indians and Islamic periods, and two entries have interacted in all periods of their on the Institute of Iranian Philology history. To begin with, there is the in Denmark. Fascicle 2 also features shared origin of the two language fami- Mahmoud Khayami, who has the beginning of a series of 12 major lies, the Iranian and the Indo-Aryan. supported the Encyclopaedia Iranica entries, under the general rubric of The earliest monuments of these fami- project since 1990 and served with IRAN, highlighting the overall aspects lies, the Avesta of northeast Iran and the great dedication as Chairman of the of Iranian history and culture.