Canadian Policy and Rhetoric Towards the Iranian Nuclear Program During Stephen Harper’S Conservative Government, 2006-2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Core 1..39 Journalweekly (PRISM::Advent3b2 10.50)

HOUSE OF COMMONS OF CANADA CHAMBRE DES COMMUNES DU CANADA 40th PARLIAMENT, 3rd SESSION 40e LÉGISLATURE, 3e SESSION Journals Journaux No. 2 No 2 Thursday, March 4, 2010 Le jeudi 4 mars 2010 10:00 a.m. 10 heures PRAYERS PRIÈRE DAILY ROUTINE OF BUSINESS AFFAIRES COURANTES ORDINAIRES TABLING OF DOCUMENTS DÉPÔT DE DOCUMENTS Pursuant to Standing Order 32(2), Mr. Lukiwski (Parliamentary Conformément à l'article 32(2) du Règlement, M. Lukiwski Secretary to the Leader of the Government in the House of (secrétaire parlementaire du leader du gouvernement à la Chambre Commons) laid upon the Table, — Government responses, des communes) dépose sur le Bureau, — Réponses du pursuant to Standing Order 36(8), to the following petitions: gouvernement, conformément à l’article 36(8) du Règlement, aux pétitions suivantes : — Nos. 402-1109 to 402-1111, 402-1132, 402-1147, 402-1150, — nos 402-1109 to 402-1111, 402-1132, 402-1147, 402-1150, 402- 402-1185, 402-1222, 402-1246, 402-1259, 402-1321, 402-1336, 1185, 402-1222, 402-1246, 402-1259, 402-1321, 402-1336, 402- 402-1379, 402-1428, 402-1485, 402-1508 and 402-1513 1379, 402-1428, 402-1485, 402-1508 et 402-1513 au sujet du concerning the Employment Insurance Program. — Sessional régime d'assurance-emploi. — Document parlementaire no 8545- Paper No. 8545-403-1-01; 403-1-01; — Nos. 402-1129, 402-1174 and 402-1268 concerning national — nos 402-1129, 402-1174 et 402-1268 au sujet des parcs parks. — Sessional Paper No. 8545-403-2-01; nationaux. — Document parlementaire no 8545-403-2-01; — Nos. -

Understanding Stephen Harper

HARPER Edited by Teresa Healy www.policyalternatives.ca Photo: Hanson/THE Tom CANADIAN PRESS Understanding Stephen Harper The long view Steve Patten CANAdIANs Need to understand the political and ideological tem- perament of politicians like Stephen Harper — men and women who aspire to political leadership. While we can gain important insights by reviewing the Harper gov- ernment’s policies and record since the 2006 election, it is also essential that we step back and take a longer view, considering Stephen Harper’s two decades of political involvement prior to winning the country’s highest political office. What does Harper’s long record of engagement in conservative politics tell us about his political character? This chapter is organized around a series of questions about Stephen Harper’s political and ideological character. Is he really, as his support- ers claim, “the smartest guy in the room”? To what extent is he a con- servative ideologue versus being a political pragmatist? What type of conservatism does he embrace? What does the company he keeps tell us about his political character? I will argue that Stephen Harper is an economic conservative whose early political motivations were deeply ideological. While his keen sense of strategic pragmatism has allowed him to make peace with both conservative populism and the tradition- alism of social conservatism, he continues to marginalize red toryism within the Canadian conservative family. He surrounds himself with Governance 25 like-minded conservatives and retains a long-held desire to transform Canada in his conservative image. The smartest guy in the room, or the most strategic? When Stephen Harper first came to the attention of political observers, it was as one of the leading “thinkers” behind the fledgling Reform Party of Canada. -

Study and Recommendations of the Standing Committee on Aboriginal

HOUSE OF COMMONS CANADA STUDY AND RECOMMENDATIONS OF THE S TANDING COMMITTE E ON AB OR IGINAL AFFAIRS AND NORTHERN DEVELOPMENT CONCERNING THE ABORIGINAL HEALING FOUNDATION Report of the Standing Committee on Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development B ruce S tanton, MP Chair J UNE 2010 40th PARLIAMENT, 3rd SESSION Published under the authority of the Speaker of the House of Commons SPEAKER’S PERMISSION Reproduction of the proceedings of the House of Commons and its Committees, in whole or in part and in any medium, is hereby permitted provided that the reproduction is accurate and is not presented as official. This permission does not extend to reproduction, distribution or use for commercial purpose of financial gain. Reproduction or use outside this permission or without authorization may be treated as copyright infringement in accordance with the Copyright Act. Authorization may be obtained on written application to the Office of the Speaker of the House of Commons. Reproduction in accordance with this permission does not constitute publication under the authority of the House of Commons. The absolute privilege that applies to the proceedings of the House of Commons does not extend to these permitted reproductions. Where a reproduction includes briefs to a Standing Committee of the House of Commons, authorization for reproduction may be required from the authors in accordance with the Copyright Act. Nothing in this permission abrogates or derogates from the privileges, powers, immunities and rights of the House of Commons and its Committees. For greater certainty, this permission does not affect the prohibition against impeaching or questioning the proceedings of the House of Commons in courts or otherwise. -

E Muslim Brotherhood and Egypt-Israel Peace Liad Porat

102 e Muslim Brotherhood and Egypt-Israel Peace Liad Porat [email protected] www.besacenter.org THE BEGIN-SADAT CENTER FOR STRATEGIC STUDIES BAR-ILAN UNIVERSITY Mideast Security and Policy Studies No. 102 The Muslim Brotherhood and Egypt-Israel Peace Liad Porat © The Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies Bar-Ilan University, Ramat Gan 5290002 Israel http://www.besacenter.org ISSN 0793-1042 January 2014 The Begin-Sadat (BESA) Center for Strategic Studies The Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies advances a realist, conservative, and Zionist agenda in the search for security and peace for Israel. It was named in memory of Menachem Begin and Anwar Sadat, whose efforts in pursuing peace lay the cornerstone for conflict resolution in the Middle East. The center conducts policy-relevant research on strategic subjects, particularly as they relate to the national security and foreign policy of Israel and Middle East regional affairs. Mideast Security and Policy Studies serve as a forum for publication or re-publication of research conducted by BESA associates. Publication of a work by BESA signifies that it is deemed worthy of public consideration but does not imply endorsement of the author’s views or conclusions. Colloquia on Strategy and Diplomacy summarize the papers delivered at conferences and seminars held by the Center for the academic, military, official and general publics. In sponsoring these discussions, the BESA Center aims to stimulate public debate on, and consideration of, contending approaches to problems of peace and war in the Middle East. The Policy Memorandum series consists of policy-oriented papers. -

A Calculus of Interest Canadian Peacekeeping Diplomacy in Cyprus, 1963-1993

Canadian Military History Volume 24 Issue 2 Article 8 2015 A Calculus of Interest Canadian Peacekeeping Diplomacy in Cyprus, 1963-1993 Greg Donaghy Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/cmh Part of the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Greg Donaghy "A Calculus of Interest Canadian Peacekeeping Diplomacy in Cyprus, 1963-1993." Canadian Military History 24, 2 (2015) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Canadian Military History by an authorized editor of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. : A Calculus of Interest Canadian Peacekeeping Diplomacy in Cyprus, 1963-1993 A Calculus of Interest Canadian Peacekeeping Diplomacy in Cyprus, 1963-1993 GREG DONAGHY Abstract: Fifty years ago, Canadian peacekeepers landed on the small Mediterranean island of Cyprus, where they stayed for thirty long years. This paper uses declassified cabinet papers and diplomatic records to tackle three key questions about this mission: why did Canadians ever go to distant Cyprus? Why did they stay for so long? And why did they leave when they did? The answers situate Canada’s commitment to Cypress against the country’s broader postwar project to preserve world order in an era marked by the collapse of the European empires and the brutal wars in Algeria and Vietnam. It argues that Canada stayed— through fifty-nine troop rotations, 29,000 troops, and twenty-eight dead— because peacekeeping worked. Admittedly there were critics, including Prime Ministers Pearson, Trudeau, and Mulroney, who complained about the failure of peacemaking in Cyprus itself. -

Iran's Gray Zone Strategy

Iran’s Gray Zone Strategy Cornerstone of its Asymmetric Way of War By Michael Eisenstadt* ince the creation of the Islamic Republic in 1979, Iran has distinguished itself (along with Russia and China) as one of the world’s foremost “gray zone” actors.1 For nearly four decades, however, the United States has struggled to respond effectively to this asymmetric “way of war.” Washington has often Streated Tehran with caution and granted it significant leeway in the conduct of its gray zone activities due to fears that U.S. pushback would lead to “all-out” war—fears that the Islamic Republic actively encourages. Yet, the very purpose of this modus operandi is to enable Iran to pursue its interests and advance its anti-status quo agenda while avoiding escalation that could lead to a wider conflict. Because of the potentially high costs of war—especially in a proliferated world—gray zone conflicts are likely to become increasingly common in the years to come. For this reason, it is more important than ever for the United States to understand the logic underpinning these types of activities, in all their manifestations. Gray Zone, Asymmetric, and Hybrid “Ways of War” in Iran’s Strategy Gray zone warfare, asymmetric warfare, and hybrid warfare are terms that are often used interchangeably, but they refer neither to discrete forms of warfare, nor should they be used interchangeably—as they often (incor- rectly) are. Rather, these terms refer to that aspect of strategy that concerns how states employ ways and means to achieve national security policy ends.2 Means refer to the diplomatic, informational, military, economic, and cyber instruments of national power; ways describe how these means are employed to achieve the ends of strategy. -

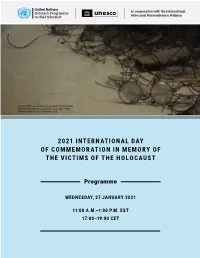

2021 International Day of Commemoration in Memory of the Victims of the Holocaust

Glasses of those murdered at Auschwitz Birkenau Nazi German concentration and death camp (1941-1945). © Paweł Sawicki, Auschwitz Memorial 2021 INTERNATIONAL DAY OF COMMEMORATION IN MEMORY OF THE VICTIMS OF THE HOLOCAUST Programme WEDNESDAY, 27 JANUARY 2021 11:00 A.M.–1:00 P.M. EST 17:00–19:00 CET COMMEMORATION CEREMONY Ms. Melissa FLEMING Under-Secretary-General for Global Communications MASTER OF CEREMONIES Mr. António GUTERRES United Nations Secretary-General H.E. Mr. Volkan BOZKIR President of the 75th session of the United Nations General Assembly Ms. Audrey AZOULAY Director-General of UNESCO Ms. Sarah NEMTANU and Ms. Deborah NEMTANU Violinists | “Sorrow” by Béla Bartók (1945-1981), performed from the crypt of the Mémorial de la Shoah, Paris. H.E. Ms. Angela MERKEL Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany KEYNOTE SPEAKER Hon. Irwin COTLER Special Envoy on Preserving Holocaust Remembrance and Combatting Antisemitism, Canada H.E. Mr. Gilad MENASHE ERDAN Permanent Representative of Israel to the United Nations H.E. Mr. Richard M. MILLS, Jr. Acting Representative of the United States to the United Nations Recitation of Memorial Prayers Cantor JULIA CADRAIN, Central Synagogue in New York El Male Rachamim and Kaddish Dr. Irene BUTTER and Ms. Shireen NASSAR Holocaust Survivor and Granddaughter in conversation with Ms. Clarissa WARD CNN’s Chief International Correspondent 2 Respondents to the question, “Why do you feel that learning about the Holocaust is important, and why should future generations know about it?” Mr. Piotr CYWINSKI, Poland Mr. Mark MASEKO, Zambia Professor Debórah DWORK, United States Professor Salah AL JABERY, Iraq Professor Yehuda BAUER, Israel Ms. -

Antisemitism Defined International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance1

Antisemitism Defined International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance1 Adopted By Canada – June 2019 In the spirit of the Stockholm Declaration that states: “With humanity still scarred by …antisemitism and xenophobia the international community shares a solemn responsibility to fight those evils” the committee on Antisemitism and Holocaust Denial called the IHRA Plenary in Budapest 2015 to adopt the following working definition of antisemitism. On 26 May 2016, the Plenary in Bucharest decided to: Adopt the following non-legally binding working definition of antisemitism: “Antisemitism is a certain perception of Jews, which may be expressed as hatred toward Jews. Rhetorical and physical manifestations of antisemitism are directed toward Jewish or non-Jewish individuals and/or their property, toward Jewish community institutions and religious facilities.” To guide IHRA in its work, the following examples may serve as illustrations: Manifestations might include the targeting of the state of Israel, conceived as a Jewish collectivity. However, criticism of Israel similar to that leveled against any other country cannot be regarded as antisemitic. Antisemitism frequently charges Jews with conspiring to harm humanity, and it is often used to blame Jews for “why things go wrong.” It is expressed in speech, writing, visual forms and action, and employs sinister stereotypes and negative character traits. Contemporary examples of antisemitism in public life, the media, schools, the workplace, and in the religious sphere could, taking into account the overall context, include, but are not limited to: § Calling for, aiding, or justifying the killing or harming of Jews in the name of a radical ideology or an extremist view of religion. -

Prism Vol. 9, No. 2 Prism About Vol

2 021 PRISMVOL. 9, NO. 2 | 2021 PRISM VOL. 9, NO. 2 NO. 9, VOL. THE JOURNAL OF COMPLEX OPER ATIONS PRISM ABOUT VOL. 9, NO. 2, 2021 PRISM, the quarterly journal of complex operations published at National Defense University (NDU), aims to illuminate and provoke debate on whole-of-government EDITOR IN CHIEF efforts to conduct reconstruction, stabilization, counterinsurgency, and irregular Mr. Michael Miklaucic warfare operations. Since the inaugural issue of PRISM in 2010, our readership has expanded to include more than 10,000 officials, servicemen and women, and practi- tioners from across the diplomatic, defense, and development communities in more COPYEDITOR than 80 countries. Ms. Andrea L. Connell PRISM is published with support from NDU’s Institute for National Strategic Studies (INSS). In 1984, Secretary of Defense Casper Weinberger established INSS EDITORIAL ASSISTANTS within NDU as a focal point for analysis of critical national security policy and Ms. Taylor Buck defense strategy issues. Today INSS conducts research in support of academic and Ms. Amanda Dawkins leadership programs at NDU; provides strategic support to the Secretary of Defense, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, combatant commands, and armed services; Ms. Alexandra Fabre de la Grange and engages with the broader national and international security communities. Ms. Julia Humphrey COMMUNICATIONS INTERNET PUBLICATIONS PRISM welcomes unsolicited manuscripts from policymakers, practitioners, and EDITOR scholars, particularly those that present emerging thought, best practices, or train- Ms. Joanna E. Seich ing and education innovations. Publication threshold for articles and critiques varies but is largely determined by topical relevance, continuing education for national and DESIGN international security professionals, scholarly standards of argumentation, quality of Mr. -

Building Canadian National Identity Within the State and Through Ice Hockey: a Political Analysis of the Donation of the Stanley Cup, 1888-1893

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 12-9-2015 12:00 AM Building Canadian National Identity within the State and through Ice Hockey: A political analysis of the donation of the Stanley Cup, 1888-1893 Jordan Goldstein The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Robert K. Barney The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Kinesiology A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Jordan Goldstein 2015 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Intellectual History Commons, Political History Commons, Political Theory Commons, and the Sports Studies Commons Recommended Citation Goldstein, Jordan, "Building Canadian National Identity within the State and through Ice Hockey: A political analysis of the donation of the Stanley Cup, 1888-1893" (2015). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 3416. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/3416 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i Stanley’s Political Scaffold Building Canadian National Identity within the State and through Ice Hockey: A political analysis of the donation of the Stanley Cup, 1888-1893 By Jordan Goldstein Graduate Program in Kinesiology A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Jordan Goldstein 2015 ii Abstract The Stanley Cup elicits strong emotions related to Canadian national identity despite its association as a professional ice hockey trophy. -

CIC Diversity Colume 6:2 Spring 2008

VOLUME 6:2 SPRING 2008 Guest Editor The Experiences of Audrey Kobayashi, Second Generation Queen’s University Canadians Support was also provided by the Multiculturalism and Human Rights Program at Canadian Heritage. Spring / printemps 2008 Vol. 6, No. 2 3 INTRODUCTION 69 Perceived Discrimination by Children of A Research and Policy Agenda for Immigrant Parents: Responses and Resiliency Second Generation Canadians N. Arthur, A. Chaves, D. Este, J. Frideres and N. Hrycak Audrey Kobayashi 75 Imagining Canada, Negotiating Belonging: 7 Who Is the Second Generation? Understanding the Experiences of Racism of A Description of their Ethnic Origins Second Generation Canadians of Colour and Visible Minority Composition by Age Meghan Brooks Lorna Jantzen 79 Parents and Teens in Immigrant Families: 13 Divergent Pathways to Mobility and Assimilation Cultural Influences and Material Pressures in the New Second Generation Vappu Tyyskä Min Zhou and Jennifer Lee 84 Visualizing Canada, Identity and Belonging 17 The Second Generation in Europe among Second Generation Youth in Winnipeg Maurice Crul Lori Wilkinson 20 Variations in Socioeconomic Outcomes of Second Generation Young Adults 87 Second Generation Youth in Toronto Are Monica Boyd We All Multicultural? Mehrunnisa Ali 25 The Rise of the Unmeltable Canadians? Ethnic and National Belonging in Canada’s 90 On the Edges of the Mosaic Second Generation Michele Byers and Evangelia Tastsoglou Jack Jedwab 94 Friendship as Respect among Second 35 Bridging the Common Divide: The Importance Generation Youth of Both “Cohesion” and “Inclusion” Yvonne Hébert and Ernie Alama Mark McDonald and Carsten Quell 99 The Experience of the Second Generation of 39 Defining the “Best” Analytical Framework Haitian Origin in Quebec for Immigrant Families in Canada Maryse Potvin Anupriya Sethi 104 Creating a Genuine Islam: Second Generation 42 Who Lives at Home? Ethnic Variations among Muslims Growing Up in Canada Second Generation Young Adults Rubina Ramji Monica Boyd and Stella Y. -

Annual Report

KENNAN INSTITUTE Annual Report October 1, 2002–September 30, 2003 The Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars One Woodrow Wilson Plaza 1300 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Washington, D.C. 20004-3027 www.wilsoncenter.org KENNAN INSTITUTE Kennan Institute Annual Report October 1, 2002–September 30, 2003 Kennan Institute Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars Kennan Moscow Project One Woodrow Wilson Plaza Galina Levina, Alumni Coordinator 1300 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Ekaterina Alekseeva, Project Manager Washington,DC 20004-3027 Irina Petrova, Office Manager Pavel Korolev, Project Officer (Tel.) 202-691-4100;(Fax) 202-691-4247 www.wilsoncenter.org/kennan Kennan Kyiv Project Yaroslav Pylynskyj, Project Manager Kennan Institute Staff Nataliya Samozvanova, Office Manager Blair A. Ruble, Director Nancy Popson, Deputy Director Research Interns 2002-2003 Margaret Paxson, Senior Associate Anita Ackermann, Jeffrey Barnett, Joseph Bould, Jamey Burho, Bram F.Joseph Dresen, Program Associate Caplan, Sapna Desai, Cristen Duncan, Adam Fuss, Anton Ghosh, Jennifer Giglio, Program Associate Andrew Hay,Chris Hrabe, Olga Levitsky,Edward Marshall, Peter Atiq Sarwari, Program Associate Mattocks, Jamie Merriman, Janet Mikhlin, Curtis Murphy,Mikhail Muhitdin Ahunhodjaev, Financial Management Specialist Osipov,Anna Nikolaevsky,Elyssa Palmer, Irina Papkov, Mark Polyak, Edita Krunkaityte, Program Assistant Rachel Roseberry,Assel Rustemova, David Salvo, Scott Shrum, Erin Trouth, Program Assistant Gregory Shtraks, Maria Sonevytsky,Erin Trouth, Gianfranco Varona, Claudia Roberts, Secretary Kimberly Zenz,Viktor Zikas Also employed at the Kennan Institute during the 2002-03 In honor of the city’s 300th anniversary, all photographs in this report program year: were taken in St. Petersburg, Russia.The photographs were provided by Jodi Koehn-Pike, Program Associate William Craft Brumfield and Vladimir Semenov.