The Wright Flyer III

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dayton,OH Sightseeing National Museum of the U.S. Air Force

Dayton,OH Sightseeing National Museum of the U.S. Air Force A “MUST SEE!” in Dayton, the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force is the world’s largest and oldest military aviation museum and Ohio’s most visited FREE tourist attraction with nearly 1.3 million annual visitors. This world-renowned museum features more than 360 aerospace vehicles and missiles and thousands of artifacts amid more than 17 acres of indoor exhibit space. Exhibits are arranged chronologically so it’s easy to visit the areas that interest you most. Examine a Wright Brothers plane, sit in a jet cockpit, walk through a NASA shuttle crew compartment trainer, or stand in awe of the world’s only permanent public display of a B-2 stealth bomber. Feeling adventurous? Check out the Morphis Movie Simulator Ride, a computer controlled simulator for the entire family. Capable of accommodating 12 passengers, the capsule rotates and gyrates on hydraulic lifts, giving the passengers the sensation of actually flying along. Dramamine may be required. Or, take in one of the multiple daily movies at the Air Force Museum Theatre’s new state-of-the-art D3D Cinema showing a wide range of films on a massive 80 foot by 60 foot screen. Satisfy your hunger at the Museum’s cafeteria (where you can even try out freeze-dried ‘astronaut ice cream!’), or shop for one-of-a-kind aviation gifts in the Museum’s impressive gift shop. And, just when you didn’t think it couldn’t happen, the best is getting even better! In 2016 a new fourth hangar will open. -

Download This PDF File

OHIO JOURNAL OF SCIENCE BOOK REVIEWS 67 Younger brother Howard Jones, who also became a between the natural environment and the rich history medical doctor, enjoyed roaming the woods and fields of this special place. and supplied most of the nests and eggs that went into Huffman Prairie today is a 114-acre fragment the family “cabinet” and became the reference library for of its original area within the Wright-Patterson Air the drawings. Genevieve’s mother, Virginia, supported Force Base, a short distance east of Dayton, Ohio. In any project her daughter was involved with but had no 1986 the natural portion of the Huffman Prairie was personal interest in ornithology and natural history. designated as an Ohio Natural Landmark Area and in She also had no training as an artist. After Genevieve’s 1990, Huffman Prairie Flying Field was designated as death, Virginia’s love for her daughter and wishes to a National Historic Landmark. It is a component of honor her memory inspired her to join her husband the National Aviation Heritage Area. and son in the project. Virginia taught herself the The book weaves together several themes: an skills needed to draw on the lithographic stones and excellent history of the land even before the Wright how to color them. Genevieve’s friend, Eliza Shulze, brothers got involved, the brothers' work on drew additional plates and helped Virginia finish the developing and improving airplane design, and the coloring of plates. In all, Genevieve drew only five eventual development of Wright-Patterson Air Force plates, Eliza did ten plates, Howard drew eleven plates Base (which encompasses the Huffman Prairie). -

The Wright Stuff

1203cent.qxd 11/13/03 2:19 PM Page 1 n a chilly North Carolina edge. It is likely that this informa- Omorning 100 years ago, two tion became the basis for the design brothers from Dayton, Ohio, at- of their early gliders. It also led them tempted a feat others considered im- to contact Octave Chanute, an possible, and their success changed American engineer who was the world. leading the way for experiments in Today we take air travel for aeronautics. granted, and rarely give a second thought to our capability to fly liter- Three problems ally anywhere in the world. But one The Wrights realized from the be- hundred years ago, the endeavors ginning that they had to solve three of the Wrights and other aeronau- problems: tical pioneers were widely viewed • Balance and control. as foolhardy. Although some of the THE WRIGHT • Wing shape and resulting lift. world’s most creative minds were • Application of power to the converging on a solution to the flight structure. problem, well-respected scientists STUFF: Of the three, they correctly recog- such as Lord Kelvin thought flight Materials in the Wright Flyer nized that balance and control were impossible. the least understood and probably In fact, Simon Newcomb, pro- The flight of the Wright Flyer was the most critical. To solve that fessor of mathematics and as- the “first in the history of the world problem, they turned to gliding ex- tronomy at Johns Hopkins Univer- periments. sity and vice-president of the in which a machine carrying a man National Academy of Sciences, had had raised itself by its own power The 1900 glider declared only 18 months before the into the air in full flight, had sailed After a few preliminary experi- successful flight at Kitty Hawk, forward without reduction of speed, ments with small kites, they built “Flight by machines heavier than air and had finally landed at a point as their first glider in 1900. -

Wright State University Magazine, Fall 2019

Wright State University CORE Scholar Wright State University Magazine Office of Marketing Fall 2019 Wright State University Magazine, Fall 2019 Office of Marketing, Wright State University Wright Sate Alumni Association Wright State University Foundation Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/wsu_magazine Part of the Mass Communication Commons Repository Citation Office of Marketing, Wright State University , Wright Sate Alumni Association , & Wright State University Foundation (2019). Wright State University Magazine, Fall 2019. This Magazine is brought to you for free and open access by the Office of Marketing at CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wright State University Magazine by an authorized administrator of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WrightStateMAGAZINE Alumni are leading the charge in the resurgence of downtown Dayton A NETFLIX ORIGINAL: CHRIS TUNG ’12 WE ARE #WRIGHTSTATESTRONG WANT EDUCATION. WILL TRAVEL. FALL 2019 Dear Wright State Magazine reader, A DOWNTOWN REBORN As we were going to press for this issue, a horrifc and senseless tragedy struck the Dayton and Wright State communities in In 2008, the recession hit downtown Dayton hard. However, this presented an opportunity the early hours of August 4, 2019. Our hearts were immediately broken for the victims’ families and for our beloved city. Our for the city to reinvent itself. In 2009, a group of business and community leaders came campus community was devastated to receive the information that a Wright State student was among the victims. In addition, together to create a local, community-wide effort to build a real future for Dayton’s urban several other members of our Wright State community were seriously impacted by the events. -

The Wright Brothers Played with As Small Boys

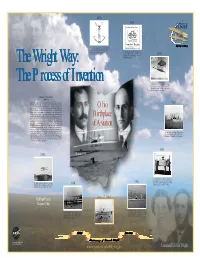

1878 1892 The Flying Toy: A small toy “helicopter”— made of wood with two twisted rubber bands to turn a small propeller—that the Wright brothers played with as small boys. The Bicycle Business: The Wright brothers opened a bicycle store in 1892. Their 1900 experience with bicycles aided them in their The Wright Way: investigations of flight. The Process of Invention The Search for Control: From their observations of how buzzards kept their balance, the Wright brothers began their aeronautical research in 1899 with a kite/glider. In 1900, they built their first glider designed to carry a pilot. Wilbur and Orville Wright Inventors Wilbur and Orville Wright placed their names firmly in the hall of great 1901 American inventors with the creation of the world’s first successful powered, heavier-than-air machine to achieve controlled, sustained flight Ohio with a pilot aboard. The age of powered flight began with the Wright 1903 Flyer on December 17, 1903, at Kill Devil Hills, NC. The Wright brothers began serious experimentation in aeronautics in 1899 and perfected a controllable craft by 1905. In six years, the Wrights had used remarkable creativity and originality to provide technical solutions, practical mechanical Birthplace design tools, and essential components that resulted in a profitable aircraft. They did much more than simply get a flying machine off the ground. They established the fundamental principles of aircraft design and engineering in place today. In 1908 and 1909, they demonstrated their flying machine pub- licly in the United States and Europe. By 1910, the Wright Company was of Aviation manufacturing airplanes for sale. -

Restoration, Preservation, and Conservation of the 1905 Wright Flyer III

Jeanne Palermo Restoration, Preservation, and Conservation of the 1905 Wright Flyer III he 1905 Wright Flyer III at museum village which he proceeded to build and Carillon Historical Park in endow. A major theme of the museum would be Dayton, Ohio, is one of the most transportation: how it changed Dayton, and how significant aircraft in the history Dayton changed transportation. Deeds’ desire to of aviation.T This relatively unknown airplane is include a Wright airplane in his museum led to called the world’s first practical airplane because, the restoration of the 1905 Wright Flyer III. with this aircraft, the Wright brothers solved all Initially, Deeds expected to construct a the remaining problems of sustained and con- replica of the 1903 “Kitty Hawk” Flyer. It was trolled flight. The 1905 Wright Flyer III is also the Orville Wright who felt that enough parts of the first plane ever to carry a passenger. 1905 machine existed to do a restoration. Wright History himself was in possession of the engine, propellers, Following their first flights at Kitty Hawk, and metal chain guides that the Wrights had North Carolina, in December 1903, Wilbur and brought back to their shop in Dayton. The frame Orville Wright returned home to Dayton for had been left in a shed at Kitty Hawk following Christmas knowing that, while they had suc- the plane’s final flights in 1908. That May, the ceeded in their dream of flying, much work plane had been refitted from its original configu- remained to make flying practical. The 1903 ration with a pilot prone on the lower wing, to Wright Flyer flew four relatively short, straight- two upright seats for a pilot and passenger. -

Americans on the Move: Grade 5 American History Lesson Plan

Wright State University CORE Scholar Gateway to Dayton Teaching American History: Citizenship, Creativity, and Invention Local and Regional Organizations 2003 Americans On the Move: Grade 5 American History Lesson Plan Timothy Binkley Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/dtah Part of the Education Commons, and the United States History Commons Repository Citation Binkley, T. (2003). Americans On the Move: Grade 5 American History Lesson Plan. https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/dtah/1 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Local and Regional Organizations at CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Gateway to Dayton Teaching American History: Citizenship, Creativity, and Invention by an authorized administrator of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact library- [email protected]. DAYT f N 'PUB L I C SCHOOLS A /Vew })Ay .Is ))AWAJIN<!!r! Name: Timothy Binkley School: Wright State University Grade 5 Level: ------ Lesson Plan Title: Americans On the Move Content Area(s) American History Learning With the development of their first practical powered aircraft, the Wright Brothers introduced a Objectives) new mode of transportation. By touring Carillon Historical Park, students willieam about different forms of transportation including the Wright Flyer. They will be asked to evaluate the merits and limitations of each, and how different forms of transportation aided in the expansion and development of the United States. [Note: this lesson plan is very similar to "Moving Along", a lesson plan for use at the Huffman Prairie Flying Field Interpretive Center / Wright Memorial. Because ofduplication, only one trip (1.5 hours = HPFFIWM, lfull day = Carillon Park) should be chosen.] Benchmarks for History Benchmark C: "Explain how new developments led to the growth of the United States." the Ohio (p.28) Academic Content Standards for Social Studies Indicators for Grade-Level indicator for Grade Five, Growth: "6. -

Increasing Technology at the Turn of the 20Th Century

Name:______________________________________________ Date:_______________ Class:____________ Short Quiz / Exit Slip: Increasing Technology at the Turn of the 20th Century Part A: Multiple Choice: Instructions: Choose the option that answers the question or completes the sentence. 1. Who helped pioneer the efforts to use electricity in cities with Thomas Edison? a. Samuel Morse b. Andrew Carnegie c. George Westinghouse d. Alexander Graham Bell 2. Who invented the telegraph? a. Thomas Edison b. Albert Einstein c. George Westinghouse d. Samuel Morse 3. What was the significance of the Bessemer Process? a. It led to the creation of the light bulb. b. It allowed voices to be carried over wires, not just beeping signals. c. It led to the ability to record sound on records. d. It led to the building of skyscrapers. 4. In what state did the Wright Brothers conduct the first flight? a. North Carolina b. Maine c. Maryland d. Ohio 5. Who invented the telephone? a. Alexander Graham Bell b. Samuel Morse c. Orville Wright d. None of the above Part B: Short Answer: Instructions: Answer the question below. 1. Which invention do you think had the most impact on American society, the light bulb, the telephone, or the airplane? Explain. ____________________________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________________________________ -

Up from Kitty Hawk Chronology

airforcemag.com Up From Kitty Hawk Chronology AIR FORCE Magazine's Aerospace Chronology Up From Kitty Hawk PART ONE PART TWO 1903-1979 1980-present 1 airforcemag.com Up From Kitty Hawk Chronology Up From Kitty Hawk 1903-1919 Wright brothers at Kill Devil Hill, N.C., 1903. Articles noted throughout the chronology provide additional historical information. They are hyperlinked to Air Force Magazine's online archive. 1903 March 23, 1903. First Wright brothers’ airplane patent, based on their 1902 glider, is filed in America. Aug. 8, 1903. The Langley gasoline engine model airplane is successfully launched from a catapult on a houseboat. Dec. 8, 1903. Second and last trial of the Langley airplane, piloted by Charles M. Manly, is wrecked in launching from a houseboat on the Potomac River in Washington, D.C. Dec. 17, 1903. At Kill Devil Hill near Kitty Hawk, N.C., Orville Wright flies for about 12 seconds over a distance of 120 feet, achieving the world’s first manned, powered, sustained, and controlled flight in a heavier-than-air machine. The Wright brothers made four flights that day. On the last, Wilbur Wright flew for 59 seconds over a distance of 852 feet. (Three days earlier, Wilbur Wright had attempted the first powered flight, managing to cover 105 feet in 3.5 seconds, but he could not sustain or control the flight and crashed.) Dawn at Kill Devil Jewel of the Air 1905 Jan. 18, 1905. The Wright brothers open negotiations with the US government to build an airplane for the Army, but nothing comes of this first meeting. -

Weekend Fly-In: Dayton, OH (KMGY) August 25‐28, 2016

Weekend Fly-In: Dayton, OH (KMGY) August 25‐28, 2016 Watch out! SEBS will exceed the limits of our southern boundaries and invade the Midwest region! After multiple requests, we will head back to Dayton, OH, the Birthplace of Aviation! Our last visit was in 2005 and much has happened since then including the National Museum of the US Air Force opening a new fourth hangar this June! We will visit the National Museum of the US Air Force as well as four of the five National Historic Landmarks within the Dayton Aviation Heritage National Historical Park including the Wright Cycle Company building, Hoover Block, Huffman Prairie Flying Field, 1905 Wright Flyer III, and Hawthorn Hill! Since we are going out of bounds, we are also changing logistics! The most important change is that we are hiring a charter bus for transportation (no 15 passenger vans). Also, with this fly‐in being in the summer and most attendees historically arriving early to beat afternoon buildups and thunderstorms, we are planning Thursday activities which are optional. For Thursday arrivals, there will be three bus shuttles from the airport to the hotel occurring at 11:30 am, 1:00 pm, and 5:00 pm. For those of you that want to participate in the Thursday activities, you should plan to arrive in time to secure your aircraft and catch the 1:00 pm shuttle. For any early arrivals prior to Thursday, we will have a bus that will depart the hotel at 10:30 am for the airport, so that you can tour the Wright “B” Flyer hangar and museum (see below). -

MS-577: Aviation Trail, Inc., Records

MS-577: Aviation Trail, Inc., Records Collection Number: MS-577 Title: Aviation Trail, Inc., Records Dates: 1924-2014 (bulk 1980-2014) Creator: Aviation Trail, Inc. Summary/Abstract: Aviation Trail, Inc., began in 1981 as an aviation-themed marketing effort in Dayton, Ohio. Initially including over 30 historical sites in the Miami Valley area relating to aviation history, a small self-guided tour brochure highlighting 16 sites was published. As of 2019, the Trail includes 18 sites. Quantity/Physical Description: 12.9 linear feet Language(s): English Repository: Special Collections and Archives, University Libraries, Wright State University, Dayton, OH 45435-0001, (937) 775-2092 Restrictions on Access: There are no restrictions on accessing material in this collection. Restrictions on Use: Aviation Trail, Inc., retains copyright to any and all of its own publications. Other copyright restrictions may apply. Unpublished manuscripts are protected by copyright. Permission to publish, quote, or reproduce must be secured from the repository and the copyright holder. Preferred Citation: [Description of item, Date, Box #, Folder #], MS-577, Aviation Trail, Inc., Records, Special Collections and Archives, University Libraries, Wright State University, Dayton, Ohio Acquisition: The Aviation Trail, Inc., Records were donated to Special Collections and Archives, Wright State University Libraries, in November 2015, by Marvin Christian, President, on behalf of the organization. Sponsor: Processing of the Aviation Trail, Inc., Records, was made possible through the generous support of Aviation Trail, Inc. MS-577: Aviation Trail, Inc., Records 1 Accruals: Additional accruals are anticipated. Separated Material: Published books (e.g., Field Guide to Flight) and organizational newsletters (e.g., Wright Flyer) have been separated to the cataloged books and periodicals collection in the Special Collections and Archives reading room. -

Wilbur & Orville Wright

Abbreviations for Sources Cited Works cited in full in the text do not appear in this list. ACANA Aero Club of America. Navigating the Air. New York Doubleday, Page & Company, 1907. ACAWMB Aero Club of America. Wright Memorial Book. New York, 1913. ADAMSF Adams, Heinrich. Flug. Leipzig: C. F. Amelangs Verlag, 1909. Aerial Age W Aerial Age Weekly. Aero Club Am Bul Aero Club of America. Bullelin. Aero J Aeronautical Journal. Allg Auto Zeit Allgemeine Automobil-Zeitung. Allg Flug Zeit Allgemeine Flugmaschinen-Zeitung. Am Aeronaut American Aeronaut. Am Legion Mag American Legion Magazine. Am Mag American Magazine. Am R Rs American Review of Reviews. AMHHF The American Heritage History of Flight. New York Simon & Schuster, 1962. ANGAEE Angle, Glenn D. Airplane Engine Encyclopedia. Dayton: Otterbein Press, 1921. ANDWF Andrews, Alfred S. The Wright Families. Rev. ed. Fort Lauderdale, Fla., 1975. ANGBW Ångström, Tord. Bröderna Wright och flygproblemets Iösning. Stockholm, Nordisk Rotogravyr, 1928. ANMAD André, Henri. Moteurs d’aviation et de dirigeables. Paris: Geisler, 1910. xiii APGAFM Apple, Nick P., and Gene Gurney. The Air Force Museum. New York: Crown Publishers, Inc., 1975. ASHWB Ash, Russell. The Wright Brothers. London: Way- land Publishers, [ 1974]. ASMEJ American Society of Mechanical Engineers. Journal. Atlan Atlantic Monthly. Aviation W Aviation Week. BBAKH Brown, Aycock. The Birth of Aviation at Kitty Hawk. N.C. Winston-Salem, N.C.: The Collins Company, 1953. BERFF Berger, Oscar. Famous Faces: Caricaturist's Scrap- book. New York and London: Hutchinson, [ 1950]. BIAFW Bia, Georges. Les Frères Wright et leur oeuvre. [Saint-Mikiel]: lmprimerie du Journal La Meuse, [ 1909]. BLASF Black, Archibald.