Plenary Session Transcript*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ALLA Press Release May 26 2015 FINAL

! ! ! A$AP ROCKY’S NEW ALBUM AT.LONG.LAST.A$AP AVAILABLE NOW ON A$AP WORLDWIDE/POLO GROUNDS MUSIC/RCA RECORDS TRENDING NO. 1 ON ITUNES IN THE US, UK, CANADA, AUSTRALIA, FRANCE, GERMANY AND MORE SOPHOMORE ALBUM FEATURES APPEARANCES BY KANYE WEST, LIL WAYNE, ScHOOLBOY Q, MIGUEL, ROD STEWART, MARK RONSON, MOS DEF, JUICY J, JOE FOX AND OTHERS [New York, NY – May 26, 2015] A$AP Rocky released his highly anticipated new album, At.Long.Last.A$AP, today (5/26) due to the album leaking a week prior to its scheduled June 2nd release date. The album is currently No. 1 at iTunes in the US, UK, Canada, Australia, France, Germany, Denmark, Finland, New Zealand, Poland, Switzerland, Russia and more. The follow-up to the charismatic Harlem MC’s 2013 release, Long.Live.A$AP, A$AP Rocky’s sophomore album, features a stellar line up of guest appearances by Rod Stewart, Miguel and Mark Ronson on “Everyday,” ScHoolboy Q on “Electric Body,” Lil Wayne on a new version of the previously released “M’$,” Kanye West and Joe Fox on “Jukebox Joints,” plus Mos Def, Juicy J, UGK and more on other standout tracks. Producers Danger Mouse, Jim Jonsin, Juicy J and Mark Ronson among others, contributes to the album’s trippy new sound. Executive Producers include Danger Mouse, A$AP Yams and A$AP Rocky with Co-Executive Producers Hector Delgado, Juicy J, Chace Johnson, Bryan Leach and AWGE. In 2013, A$AP Rocky announced his global arrival in a major way with his chart- topping debut album LONG.LIVE.A$AP. -

The Grey Album and Musical Composition in Configurable Culture

What Did Danger Mouse Do? The Grey Album and Musical Composition in Configurable Culture This article uses The Grey Album, Danger Mouse’s 2004 mashup of Jay-Z’s Black Album with the Beatles’“White Album,” to explore the ontological status of mashups, with a focus on determining what sort of creative work a mashup is. After situating the album in relation to other types of musical borrowing, I provide brief analyses of three of its tracks and build upon recent research in configurable-music practices to argue that the album is best conceptualized as a type of musical performance. Keywords: The Grey Album, The Black Album, the “White Album,” Danger Mouse, Jay-Z, the Beatles, mashup, configurable music. Downloaded from captions. What’s most embarrassing about this is how http://mts.oxfordjournals.org/ immensely improved both cartoons turned out to be.”2 n 1989 Gary Larson published The PreHistory of The Far Larson’s tantalizing use of quotation marks around “acci- Side, a retrospective of his groundbreaking cartoon. In a dentally” implies that the editor responsible for switching the I section of the book titled Mistakes—Mine and Theirs, captions may have done so deliberately. If we assume this to be Larson discussed a couple of curious instances when the Dayton the case and agree that both cartoons are improved, a number of Daily News switched the captions for The Far Side with the one questions emerge. What did the editor do? He/she did not for Dennis the Menace, its neighbor on the comics page. The come up with a concept, did not draw a cartoon, and did not first of these two instances had, by far, the funnier result: on the compose a caption. -

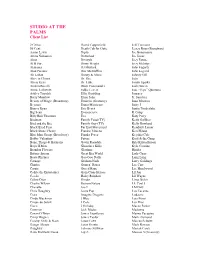

Client and Artist List

STUDIO AT THE PALMS Client List 2 Cellos David Copperfield Jeff Timmons 50 Cent Death Cab for Cutie Jersey Boys (Broadway) Aaron Lewis Diplo Joe Bonamassa Akina Nakamori Disturbed Joe Jonas Akon Divinyls Joey Fatone Al B Sure Dizzy Wright Joey McIntyre Alabama DJ Mustard John Fogarty Alan Parsons Doc McStuffins John Legend Ali Lohan Donny & Marie Johnny Gill Alice in Chains Dr. Dre JoJo Alicia Keys Dr. Luke Jordin Sparks Andrea Bocelli Duck Commander Josh Gracin Annie Leibovitz Eddie Levert Jose “Pepe” Quintano Ashley Tinsdale Ellie Goulding Journey Barry Manilow Elton John Jr. Sanchez Beauty of Magic (Broadway) Eminem (Grammy) Juan Montero Beyonce Ennio Morricone Juicy J Bianca Ryan Eric Benet Justin Timberlake Big Sean Evanescence K Camp Billy Bob Thornton Eve Katy Perry Birdman Family Feud (TV) Keith Galliher Bird and the Bee Family Guy (TV) Kelly Rowland Black Eyed Peas Far East Movement Kendrick Lamar Black Stone Cherry Frankie Moreno Keri Hilson Blue Man Group (Broadway) Franky Perez Keyshia Cole Bobby Valentino Future Kool & the Gang Bone, Thugs & Harmony Gavin Rossdale Kris Kristofferson Boyz II Men Ghostface Killa Kyle Cousins Brandon Flowers Gloriana Hinder Britney Spears Great Big World Lady Gaga Busta Rhymes Goo Goo Dolls Lang Lang Carnage Graham Nash Larry Goldings Charise Guns n’ Roses Lee Carr Cassie Gucci Mane Lee Hazelwood Cedric the Entertainer Gym Class Heroes Lil Jon Cee-lo Haley Reinhart Lil Wayne Celine Dion Hinder Limp Bizkit Charlie Wilson Human Nature LL Cool J Chevelle Ice-T LMFAO Chris Daughtry Icona Pop Los -

WXYC Brings You Gems from the Treasure of UNC's Southern

IN/AUDIBLE LETTER FROM THE EDITOR a publication of N/AUDIBLE is the irregular newsletter of WXYC – your favorite Chapel Hill radio WXYC 89.3 FM station that broadcasts 24 hours a day, seven days a week out of the Student Union on the UNC campus. The last time this publication came out in 2002, WXYC was CB 5210 Carolina Union Icelebrating its 25th year of existence as the student-run radio station at the University of Chapel Hill, NC 27599 North Carolina at Chapel Hill. This year we celebrate another big event – our tenth anni- USA versary as the first radio station in the world to simulcast our signal over the Internet. As we celebrate this exciting event and reflect on the ingenuity of a few gifted people who took (919) 962-7768 local radio to the next level and beyond Chapel Hill, we can wonder request line: (919) 962-8989 if the future of radio is no longer in the stereo of our living rooms but on the World Wide Web. http://www.wxyc.org As always, new technology brings change that is both exciting [email protected] and scary. Local radio stations and the dedicated DJs and staffs who operate them are an integral part of vibrant local music communities, like the one we are lucky to have here in the Chapel Hill-Carrboro Staff NICOLE BOGAS area. With the proliferation of music services like XM satellite radio Editor-in-Chief and Live-365 Internet radio servers, it sometimes seems like the future EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Nicole Bogas of local radio is doomed. -

Danger Mouse's Grey Album, Mash-Ups, and the Age of Composition

Danger Mouse's Grey Album, Mash-Ups, and the Age of Composition Philip A. Gunderson © 2004 Post-Modern Culture 15.1 Review of: Danger Mouse (Brian Burton), The Grey Album, Bootleg Recording 1. Depending on one's perspective, Danger Mouse's (Brian Burton's) Grey Album represents a highpoint or a nadir in the state of the recording arts in 2004. From the perspective of music fans and critics, Burton's creation--a daring "mash-up" of Jay-Z's The Black Album and the Beatles' eponymous 1969 work (popularly known as The White Album)--shows that, despite the continued corporatization of music, the DIY ethos of 1970s punk remains alive and well, manifesting in sampling and low-budget, "bedroom studio" production values. From the perspective of the recording industry, Danger Mouse's album represents the illegal plundering of some of the most valuable property in the history of pop music (the Beatles' sound recordings), the sacrilegious re-mixing of said recordings with a capella tracks of an African American rapper, and the electronic distribution of the entire album to hundreds of thousands of listeners who appear vexingly oblivious to current copyright law. That there would be a schism between the interests of consumers and the recording industry is hardly surprising; tension and antagonism characterize virtually all forms of exchange in capitalist economies. What is perhaps of note is that these tensions have escalated to the point of the abandonment of the exchange relationship itself. Music fans, fed up with the high prices (and outright price-fixing) of commercially available music, have opted to share music files via peer-to-peer file sharing networks, and record labels are attempting in response to coerce music fans back into the exchange relationship. -

Adele: 25 Free

FREE ADELE: 25 PDF Adele | 70 pages | 15 Feb 2016 | Music Sales Ltd | 9781783057719 | English | London, United Kingdom 25 | Adele Wiki | Fandom It seems like Adele just keeps getting better. Every track is great, so it's hard to pick favorites! Outstanding job Really there's not much more to say. This is a fabulous work of art and at the price you pay, through Walmart online, it's a steal! Each song is fantastic for so many reason's! I can def see what all the Adele: 25 was around this cd. Just love it. Esp song number 2. Adele: 25 at Walmart. Your email address will never be sold or distributed to a third party for any reason. Sorry, but we can't respond to individual comments. If you need immediate assistance, please contact Customer Care. Your feedback helps us make Walmart shopping better for millions of customers. Recent searches Clear All. Enter Location. Update location. Learn more. Report incorrect product information. Walmart Free Adele: 25 delivery. Pickup not available. Add to list. Add to registry. The cinematic video for quot;Helloquot; was shot in the countryside surrounding Montreal and is directed by the celebrated young Canadian director Xavier Dolan Mommy, Tom at the Farm. About This Item. We aim to show you accurate product information. Manufacturers, suppliers and Adele: 25 provide what you see here, Adele: 25 we have not verified it. See our disclaimer. Specifications Music Genre Rock. Customer Comments What others said when purchasing this item. I'm getting it for my mom. Angela, purchased on September 2, Write a review See all reviews Write a review. -

The Cambridge Companion to the Beatles Edited by Kenneth Womack Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-68976-2 - The Cambridge Companion to the Beatles Edited by Kenneth Womack Index More information Index Abbey Road, 56, 58–60, 83, 125, 132–6, 146, Best, Mona, 23 149, 153, 167, 199, 215, 233 Best, Pete, 9, 10, 11, 13, 22, 24, 26, 33, 34 Adorno, Theodor, 77, 82, 88, 225 Big 3, the, 22 ADT (Artificial Double Tracking), 51 BillyJ.KramerandtheDakotas, 70, 73 Aguilera, Christina, 243 Bishop, Malden Grange, 110–11 Alexander, George, 143 Black Dyke Mills Band, 118, 146 All Things Must Pass, 128, 130, 149, 154, 156, Black, Cilla, 20 157–8, 159, 163, 170, 179 Blackbird, 225 Alpert, Richard, 90, 103 Blake, Peter, 98, 180 Andrew, Sam, 93 Bonzo Dog Band, the, 105, 118 Animals, the, 41, 73, 108, 226 Bowie, David, 175 Antonioni, Michelangelo, 207 Bradby, Barbara, 228–9 Apple Records, 128, 142–52, 222, 250 Brahms, Johannes, 186 Ardagh, Philip, 225 Braine, John, 207 Armstrong, Louis, 34, 230 Brainwashed, 179 Asher, Jane, 113, 145 Brecht, Bertolt, 78 Asher, Peter, 144, 145, 151 Brodax, Al, 116 Aspinall, Neil, 13, 143, 237, 238, 250, 251 Bromberg, David, 156 Astaire, Fred, 122 Brookhiser, Richard, 176 Axton, Hoyt, 157 Brown, Peter, 12 Ayckbourn, Alan, 207 Burdon, Eric, 108 Burnett, Johnny, 156 Bach, Barbara, 178 Burroughs, William, 209 Back in the US, 239 Byrds, the, 75, 93, 104, 130, 226, 233 Back to the Egg, 168 Bad Boy, 157 Caine, Michael, 206, 207 Badfinger, 150, 159, 222 Caldwell, Alan, 22 Bailey, David, 206, 207 Candy, 155, 221 Baird, Julia, 21 Carlos, John, 112 Baker, Ginger, 149 Carroll, Lewis, 51 Band on the Run, -

BOONE-DISSERTATION.Pdf

Copyright by Christine Emily Boone 2011 The Dissertation Committee for Christine Emily Boone Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Mashups: History, Legality, and Aesthetics Committee: James Buhler, Supervisor Byron Almén Eric Drott Andrew Dell‘Antonio John Weinstock Mashups: History, Legality, and Aesthetics by Christine Emily Boone, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2011 Acknowledgements I want to first acknowledge those people who had a direct influence on the creation of this document. My brother, Philip, introduced me mashups a few years ago, and spawned my interest in the subject. Dr. Eric Drott taught a seminar on analyzing popular music where I was first able to research and write about mashups. And of course, my advisor, Dr. Jim Buhler has given me immeasurable help and guidance as I worked to complete both my degree and my dissertation. Thank you all so much for your help with this project. Although I am the only author of this dissertation, it truly could not have been completed without the help of many more people. First I would like to thank all of my professors, colleagues, and students at the University of Texas for making my time here so productive. I feel incredibly prepared to enter the field as an educator and a scholar thanks to all of you. I also want to thank all of my friends here in Austin and in other cities. -

Fair Use Avoidance in Music Cases Edward Lee Chicago-Kent College of Law, [email protected]

Boston College Law Review Volume 59 | Issue 6 Article 2 7-11-2018 Fair Use Avoidance in Music Cases Edward Lee Chicago-Kent College of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/bclr Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Edward Lee, Fair Use Avoidance in Music Cases, 59 B.C.L. Rev. 1873 (2018), https://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/bclr/vol59/iss6/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Boston College Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FAIR USE AVOIDANCE IN MUSIC CASES EDWARD LEE INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 1874 I. FAIR USE’S RELEVANCE TO MUSIC COMPOSITION ................................................................ 1878 A. Fair Use and the “Borrowing” of Copyrighted Content .................................................. 1879 1. Transformative Works ................................................................................................. 1879 2. Examples of Transformative Works ............................................................................ 1885 B. Borrowing in Music Composition ................................................................................... -

The Spectral Voice and 9/11

SILENCIO: THE SPECTRAL VOICE AND 9/11 Lloyd Isaac Vayo A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2010 Committee: Ellen Berry, Advisor Eileen C. Cherry Chandler Graduate Faculty Representative Cynthia Baron Don McQuarie © 2010 Lloyd Isaac Vayo All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Ellen Berry, Advisor “Silencio: The Spectral Voice and 9/11” intervenes in predominantly visual discourses of 9/11 to assert the essential nature of sound, particularly the recorded voices of the hijackers, to narratives of the event. The dissertation traces a personal journey through a selection of objects in an effort to seek a truth of the event. This truth challenges accepted narrativity, in which the U.S. is an innocent victim and the hijackers are pure evil, with extra-accepted narrativity, where the additional import of the hijacker’s voices expand and complicate existing accounts. In the first section, a trajectory is drawn from the visual to the aural, from the whole to the fragmentary, and from the professional to the amateur. The section starts with films focused on United Airlines Flight 93, The Flight That Fought Back, Flight 93, and United 93, continuing to a broader documentary about 9/11 and its context, National Geographic: Inside 9/11, and concluding with a look at two YouTube shorts portraying carjackings, “The Long Afternoon” and “Demon Ride.” Though the films and the documentary attempt to reattach the acousmatic hijacker voice to a visual referent as a means of stabilizing its meaning, that voice is not so easily fixed, and instead gains force with each iteration, exceeding the event and coming from the past to inhabit everyday scenarios like the carjackings. -

Everybody's Got Something to Hide Except for Me and My Lawsuit

Schneiderman, D. (2006). Everybody’s Got Something to Hide Except for Me and My Lawsuit: William S. Burroughs, DJ Danger Mouse, and the Politics of “Grey Tuesday”. Plagiary: Cross‐Disciplinary Studies in Plagiarism, Fabrica‐ tion, and Falsification, 191‐206. Everybody’s Got Something to Hide Except for Me and My Lawsuit: William S. Burroughs, DJ Danger Mouse, and the Politics of “Grey Tuesday” Davis Schneiderman E‐mail: [email protected] Abstract persona is replaced by a collaborative ethic that On February 24, 2004, approximately 170 Web makes the audience complicit in the success of the sites hosted a controversial download of DJ Danger “illegal” endeavor. Mouse’s The Grey Album, a “mash” record com- posed of The Beatles’s The White Album and Jay-Z’s The Black Album. Many of the participating Web sites received “cease and desist” letters from EMI Mash-Ups: A Project for Disastrous Success (The Beatles’s record company), yet the so-called “Grey Tuesday” protest resulted in over 100,000 If the 2005 Grammy Awards broadcast was the downloads of the record. While mash tunes are a moment that cacophonous pop‐music “mash‐ relatively recent phenomenon, the issues of owner- ups” were first introduced to grandma in Peoria, ship and aesthetic production raised by “Grey Tues- day” are as old as the notion of the literary “author” the strategy’s commercial(ized) pinnacle may as an autonomous entity, and are complicated by have been the November 2004 CD/DVD release deliberate literary plagiarisms and copyright in- by rapper Jay‐Z and rockers Linkin Park, titled, fringements. -

The Snow Miser Song 6Ix Toys - Tomorrow's Children (Feat

(Sandy) Alex G - Brite Boy 1910 Fruitgum Company - Indian Giver 2 Live Jews - Shake Your Tuchas 45 Grave - The Snow Miser Song 6ix Toys - Tomorrow's Children (feat. MC Kwasi) 99 Posse;Alborosie;Mama Marjas - Curre curre guagliò still running A Brief View of the Hudson - Wisconsin Window Smasher A Certain Ratio - Lucinda A Place To Bury Strangers - Straight A Tribe Called Quest - After Hours Édith Piaf - Paris Ab-Soul;Danny Brown;Jhene Aiko - Terrorist Threats (feat. Danny Brown & Jhene Aiko) Abbey Lincoln - Lonely House - Remastered Abbey Lincoln - Mr. Tambourine Man Abner Jay - Woke Up This Morning ACID MOTHERS TEMPLE - Are We Experimental? Adolescents - Democracy Adrian Sherwood - No Dog Jazz Afro Latin Vintage Orchestra - Ayodegi Afrob;Telly Tellz;Asmarina Abraha - 808 Walza Afroman - I Wish You Would Roll A New Blunt Afternoons in Stereo - Kalakuta Republik Afu-Ra - Whirlwind Thru Cities Against Me! - Transgender Dysphoria Blues Aim;Qnc - The Force Al Jarreau - Boogie Down Alabama Shakes - Joe - Live From Austin City Limits Albert King - Laundromat Blues Alberta Cross - Old Man Chicago Alex Chilton - Boplexity Alex Chilton;Ben Vaughn;Alan Vega - Fat City Alexia;Aquilani A. - Uh La La La AlgoRythmik - Everybody Gets Funky Alice Russell - Humankind All Good Funk Alliance - In the Rain Allen Toussaint - Yes We Can Can Alvin Cash;The Registers - Doin' the Ali Shuffle Amadou & Mariam - Mon amour, ma chérie Ananda Shankar - Jumpin' Jack Flash Andrew Gold - Thank You For Being A Friend Andrew McMahon in the Wilderness - Brooklyn, You're