London's Sonic Space

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1995 Spring Program Guide

c;; 5([1 ~ -H~J JJ _0~ ·. o:'6-:5i--S ,· I ~~ - - - ---------------------- -·· ,.----··--·---- i ' /') l ' ,/ ·' !! ' , r: _;( - ./' ' . ·'1i .1 'I ' '-----·•--- ------- . ;: ._;. : .. ~ .. :' · .. ~ .. ' MONDAY: the wack. 12-2 am: "The Glory Box" Kara Fiegenschuh 8-lOam: "The Circus Freakshow" Nina Aronson Shoegazers and slackers from the 50 states and A mix of everything: New sounds, groovy Europe. rhythms, and upbeat melodies. Music that 2-4 am: "Fishin' the Northwest" Michael Wolfe makes you feel good, whether you feel good The Edge tries to tell you what Seattle music is. about life, pain, whatever. None of that here, we'll show you what real 10-12 pm: "Punker Than You" Stephanie Boehmer Sea ttli tes listen to. Spinnin' the punk and oi! anthems from the late '70's and early '80's. There's no show more WEDNESDAY: desperate and more bored. 12-2pm: "Classical Lunchbox" Chris Schiffer 8-10 am: "Swingcheese" Robin Moore Chris will play classical music and will try not to Two hours of swing and jazz with snappy vocals, DJ in a monotone NPR voice. There is the swingin' instrumentals and an ever lovin open possibility of guest composers/musicians. request line. In all things be fabulous baby. 2-4pm: "Variety Show" Thien-Bao Thuc Phi 10-12 am: "Kara and Joanna's Office Hours" One show I may devote to hip hop, one to show We'll play you music while we clean the office tunes, or maybe on the same day I'll bust Craig and organize things. Mack and Sophie B. Hawkins back to back. 12-2 pm: "A Night at the Village Vanguard" Chris 4-6pm: "Music for the Fall Guy" Nate Sparks Stromquist Country and Western music from the past and The best jazz you'll hear before midnight. -

Cultural Production in Andrea Levy's Small Island Author: Alicia E

ENTERTEXT Identity as Cultural Production in Andrea Levy's Small Island Author: Alicia E. Ellis Source: EnterText, “Special Issue on Andrea Levy 9,” (2012): 69-83. Abstract Andrea Levy's Small Island (2004) presents a counter-history of the period before and after World War II (1939-1945) when men and women from the Caribbean volunteered for all branches of the British armed services and many eventually immigrated to London after the war officially ended in 1945. Her historical novel moves back and forth between 1924 and 1948 as well as across national borders and cultures. Levy’s novel, written more than fifty years after the first Windrush arrival, creates a common narrative of nation and identity in order to understand the experiences of Black people in Britain. Small Island—structured around four competing voices whose claims of textual, personal and historical truth must be acknowledged—refuses to establish a singular articulation of the experience of migration and empire. In this essay, I focus on discrete moments in the “Prologue” in Levy’s Small Island in order to think through the formation of discursive identity through the encounter with others and the necessity of accommodating difference. Small Island forecloses the possibility of addressing modern multiculturalism as a purported ‘happy ending’ in light of Levy’s formulation of the Windrush moment as disruptive, violent, and overwhelmed by flawed characters. Yet, through the space of writing, she also invites the reader to experience moments of encounter and negotiate the often competing claims on nationhood, citizenship, and culture. Identity as Cultural Production in Andrea Levy's Small Island Alicia E. -

State of Bass

First published by Velocity Press 2020 velocitypress.uk Copyright © Martin James 2020 Cover design: Designment designment.studio Typesetting: Paul Baillie-Lane pblpublishing.co.uk Photography: Cleveland Aaron, Andy Cotterill, Courtney Hamilton, Tristan O’Neill Martin James has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identied as the author of this work All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, in any form or by any means, without permission from the publisher While the publishers have made every reasonable eort to trace the copyright owners for some of the photographs in this book, there may be omissions of credits, for which we apologise. ISBN: 9781913231026 1: Ag’A THE JUNGLISTS NAMING THE SOUND, LOCATING THE SCENE ‘It always has been such a terrible name. I’ve never known any other type of music to get so misconstrued by its name.’ (Rob Playford, 1996) Of all of the dance music genres, none has been surrounded with quite so much controversy over its name than jungle. No sooner had it been coined than exponents of the scene were up in arms about the racist implications. Arguments raged over who rst used the term and many others simply refused to acknowledge the existence of the moniker. It wasn’t the rst time that jungle had been used as a way to describe a sound. Kool and the Gang had called their 1973 funk standard Jungle Boogie, while an instrumental version with an overdubbed ute part and additional percussion instruments was titled Jungle Jazz. The song ends with a Tarzan yell and features grunting, panting and scatting throughout. -

Conclusion 60

Being Black, Being British, Being Ghanaian: Second Generation Ghanaians, Class, Identity, Ethnicity and Belonging Yvette Twumasi-Ankrah UCL PhD 1 Declaration I, Yvette Twumasi-Ankrah confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 2 Table of Contents Declaration 2 List of Tables 8 Abstract 9 Impact statement 10 Acknowledgements 12 Chapter 1 - Introduction 13 Ghanaians in the UK 16 Ghanaian Migration and Settlement 19 Class, status and race 21 Overview of the thesis 22 Key questions 22 Key Terminology 22 Summary of the chapters 24 Chapter 2 - Literature Review 27 The Second Generation – Introduction 27 The Second Generation 28 The second generation and multiculturalism 31 Black and British 34 Second Generation – European 38 US Studies – ethnicity, labels and identity 40 Symbolic ethnicity and class 46 Ghanaian second generation 51 Transnationalism 52 Second Generation Return migration 56 Conclusion 60 3 Chapter 3 – Theoretical concepts 62 Background and concepts 62 Class and Bourdieu: field, habitus and capital 64 Habitus and cultural capital 66 A critique of Bourdieu 70 Class Matters – The Great British Class Survey 71 The Middle-Class in Ghana 73 Racism(s) – old and new 77 Black identity 83 Diaspora theory and the African diaspora 84 The creation of Black identity 86 Black British Identity 93 Intersectionality 95 Conclusion 98 Chapter 4 – Methodology 100 Introduction 100 Method 101 Focus of study and framework(s) 103 -

Smash Hits Volume 60

35p USA $1 75 March I9-April 1 1981 W I including MIND OFATOY RESPECTABLE STREE CAR TROUBLE TOYAH _ TALKING HEADS in colour FREEEZ/LINX BEGGAR &CO , <0$& Of A Toy Mar 19-Apr 1 1981 Vol. 3 No. 6 By Visage on Polydor Records My painted face is chipped and cracked My mind seems to fade too fast ^Pg?TF^U=iS Clutching straws, sinking slow Nothing less, nothing less A puppet's motion 's controlled by a string By a stranger I've never met A nod ofthe head and a pull of the thread on. Play it I Go again. Don't mind me. just work here. I don't know. Soon as a free I can't say no, can't say no flexi-disc comes along, does anyone want to know the poor old intro column? Oh, no. Know what they call me round here? Do you know? The flannel panel! The When a child throws down a toy (when child) humiliation, my dears, would be the finish of a more sensitive column. When I was new you wanted me (down me) Well, I can see you're busy so I won't waste your time. I don't suppose I can drag Now I'm old you no longer see you away from that blessed record long enough to interest you in the Ritchie (now see) me Blackmore Story or part one of our close up on the individual members of The Jam When a child throws down a toy (when toy) (and Mark Ellen worked so hard), never mind our survey of the British funk scene. -

Funk Soul Brother – Repertoire 2018

FUNK SOUL BROTHER – REPERTOIRE 2018 PARTY MUSIC & DANCE FLOOR FILLERS! A Little Less Conversation - Elvis Another One Bites The Dust - Queen Beat It - Michael Jackson Billie Jean - Michael Jackson Blame It On The Boogie - Jackson 5 Blurred Lines - Robin Thicke Cake By The Ocean - DNCE Canned Heat - Jamiroquai Car Wash - Rose Royce Cold Sweat - James Brown Cosmic Girl - Jamiroquai Dance To The Music - Sly & The Family Stone Don't Stop Til You Get Enough - Michael Jackson Get Down On It - Kool and the Gang Get Down Saturday Night - Oliver Cheatham Get Lucky - Daft Punk Get Up Offa That Thing - James Brown Good Times - Chic Groove Is In The Heart - Dee-Lite Happy - Pharrell Williams Higher And Higher - Jackie Wilson I Believe in Mircales - Jackson Sisters I Wish - Stevie Wonder It's Your Thing - The Isley Brothers Kiss - Prince Ladies Night - Kool and the Gang Lady Marmalade - Labelle Le Freak - Chic Let's Stay Together - Al Green (continued) +44 (0)1572 335108 • [email protected] • www.pureartists.co.uk Long Train Running - Doobie Brothers Locked Out of Heaven - Bruno Mars Love Shack - B52s Mercy - The Third Degree/Duffy Move On Up - Curtis Mayfield Move Your Feet - Junior Senior Mr Big Stuff - Jean Knight Mustang Sally - Wilson Pickett Papa’s Got A Brand New Bag - James Brown Pick Up The Pieces - Average White Band Play That Funky Music - Wild Cherry Rather Be - Clean Bandit ft. Jess Glynne Rehab - Amy Winehouse Respect - Aretha Franklin Signed Sealed Delivered - Stevie Wonder Sir Duke - Stevie Wonder Superstition - Stevie Wonder -

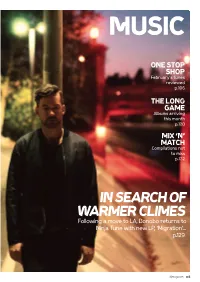

IN SEARCH of WARMER CLIMES Following a Move to LA, Bonobo Returns to Ninja Tune with New LP, ‘Migration’

MUSIC ONE STOP SHOP February’s tunes reviewed p.106 THE LONG GAME Albums arriving this month p.128 MIX ‘N’ MATCH Compilations not to miss p.132 IN SEARCH OF WARMER CLIMES Following a move to LA, Bonobo returns to Ninja Tune with new LP, ‘Migration’... p.129 djmag.com 105 HOUSE BEN ARNOLD QUICKIES Roberto Clementi Avesys EP [email protected] Pets Recordings 8.0 Sheer class from Roberto Clementi on Pets. The title track is brooding and brilliant, thick with drama, while 'Landing A Man'’s relentless thump betrays a soft and gentle side. Lovely. Jagwar Ma Give Me A Reason (Michael Mayer Does The Amoeba Remix) Marathon MONEY 8.0 SHOT! Showing that he remains the master (and managing Baba Stiltz to do so in under seven minutes too), Michael Mayer Is Everything smashes this remix of baggy dance-pop dudes Studio Barnhus Jagwar Ma out of the park. 9.5 The unnecessarily young Baba Satori Stiltz (he's 22) is producing Imani's Dress intricate, brilliantly odd house Crosstown Rebels music that bearded weirdos 8.0 twice his age would give their all chopped hardcore loops, and a brilliance from Tact Recordings Crosstown is throwing weight behind the rather mid-life crises for. Think the bouncing bassline. Sublime work. comes courtesy of roadman (the unique sound of Satori this year — there's an album dizzying brilliance of Robag small 'r' is intentional), aka coming — but ignore the understatedly epic Ewan Whrume for a reference point, Dorsia Richard Fletcher. He's also Tact's Pearson mixes of 'Imani's Dress' at your peril. -

Capturing Hip Hop Histories

capturing hip hop histories SOUTH-WEST HEADZ Master Blast Roadshow poster by Raz (Kilo), 1986. Photograph: Kilo. First published 2021 2021 Adam de Paor-Evans Cover graff by Remser Remser started writing in 1997 after seeing dubs and pieces by Sceo, Fixer, Teach, and G-Sane at the M5 pillar spot in Exeter. His school bus used to loop around Sannerville Way and the pieces could be seen from the road as well as the train. A couple of years prior to this, Remser’s mum randomly bought him a copy of Spraycan Art, and he knew straight away that it was something he wanted to be part of. In early 2000 he moved to London and hooked up with the DNK/CWR boys, they were way better than him and super-active but this experience pushed him to develop his style and learn about all aspects of graffiti writing. Respect and love to all of the South-West writers and hip hop headz, too many to mention but you know who you are! DNK CWR Waxnerds forever... Approved for free Cultural Works Creative Commons Licence Attribution 4.0 International Published by Squagle House, United Kingdom Printed in Great Britain Although every precaution has been taken in the preparation of this publication, the publisher and author assume no responsibility for errors or omissions. Neither is any liability assumed for damages resulting from the use of information contained herein. RHYTHM•obscura: revealing hidden histories through ethnomusicology and cultural theory is a long-term research venture that explores the relationships of the non-obvious and regional-rural phenomena within music cultures. -

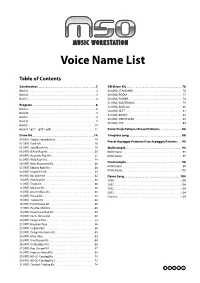

M50 Voice Name List

Voice Name List Table of Contents Combination . .2 GM Drum Kit . 76 Bank A. .2 48 (GM): STANDARD . 76 Bank B. .3 49 (GM): ROOM . 77 Bank C. .4 50 (GM): POWER. 78 51 (GM): ELECTRONIC . 79 Program . .6 52 (GM): ANALOG . 80 Bank A. .6 53 (GM): JAZZ . 81 Bank B. .7 54 (GM): BRUSH . 82 Bank C. .8 55 (GM): ORCHESTRA. 83 Bank D . .9 56 (GM): SFX . 84 Bank E . 10 Bank G / g(1)…g(9) / g(d). 11 Drum Track Patterns/Preset Patterns. 86 Drum Kit . .14 Template song . 88 00 (INT): Studio Standard Kit. 14 Preset Arpeggio Patterns/User Arpeggio Patterns . 90 01 (INT): Funk Kit. 16 02 (INT): Jazz/Brush Kit . 18 Multisample. 94 03 (INT): B.Real Rap Kit . 20 ROM mono . 94 04 (INT): Acoustic Pop Kit. 22 ROM stereo . 97 05 (INT): Wild Rock Kit . 24 Drumsample . 98 06 (INT): New Processed Kit. 26 07 (INT): Electro Rock Kit . 28 ROM mono . 98 08 (INT): Insane FX Kit . 30 ROM stereo . 103 09 (INT): Nu Style Kit . 32 Demo Song. 104 10 (INT): Hip Hop Kit . 34 S000 . 104 11 (INT): Tricki kit. 36 S001 . 104 12 (INT): Mashed Kit. 38 S002 . 104 13 (INT): Drum'n'Bass Kit . 40 S003 . 104 14 (INT): House Kit . 42 Cue List . 104 15 (INT): Trance Kit . 44 16 (INT): Hard House Kit . 46 17 (INT): Psycho-Chill Kit . 48 18 (INT): Down Low Rap Kit. 50 19 (INT): Orch.-Ethnic Kit . 52 20 (INT): Original Perc . 54 21 (INT): Brazilian Perc. 56 22 (INT): Cuban Perc . -

Free 70S Disco Samples

Free 70s disco samples The royalty free 70s disco loops, samples and sounds listed here have been kindly uploaded by other users and are free to use in your project. If you use any of. Disco music loops, stock samples, royalty free downloads. Acid, FL Studio Download bpm Disco Drum by rasputin - 70s Disco Beat-- Highly Swung. KVR Forum Topic: 'Funk/70's Disco Samples ' - Hi all, I want to "disco-fy" my sound. Does anyone know where I can get any kind of disco sas disco drum kit? (Topic in the 'Samplers, Sampling. The glory years of disco may have been in the late '70s and early '80s, but its dancefloor friendly sound has never really gone away. Here some of the classic disco drums we've used over the years. Perfect for filling up your drums and giving them that live drum feel. All samples were sampled. True Disco by Loopmasters is on Splice Sounds. collection of royalty free disco samples since Jon Travolta hung up his flares. True Disco is an electrifying collection of Live instrument loops recorded through Worry no more about Licencing issues with those dodgy samples of old Disco records, get the full 70s Vibe here. Inject your music with authentic disco flavours with the hottest royalty-free sample packs, loops, MIDI, patches and presets - all available to audition instantly and. Download FREE Disco sounds - royalty-free! Find the Disco sound you are looking for in seconds. Free Soul sample pack downloads from Samplephonics. Check the website for a huge range of free Soul drum loops, instrument samples, sounds & sample libraries. -

The A-Z of Brent's Black Music History

THE A-Z OF BRENT’S BLACK MUSIC HISTORY BASED ON KWAKU’S ‘BRENT BLACK MUSIC HISTORY PROJECT’ 2007 (BTWSC) CONTENTS 4 # is for... 6 A is for... 10 B is for... 14 C is for... 22 D is for... 29 E is for... 31 F is for... 34 G is for... 37 H is for... 39 I is for... 41 J is for... 45 K is for... 48 L is for... 53 M is for... 59 N is for... 61 O is for... 64 P is for... 68 R is for... 72 S is for... 78 T is for... 83 U is for... 85 V is for... 87 W is for... 89 Z is for... BRENT2020.CO.UK 2 THE A-Z OF BRENT’S BLACK MUSIC HISTORY This A-Z is largely a republishing of Kwaku’s research for the ‘Brent Black Music History Project’ published by BTWSC in 2007. Kwaku’s work is a testament to Brent’s contribution to the evolution of British black music and the commercial infrastructure to support it. His research contained separate sections on labels, shops, artists, radio stations and sound systems. In this version we have amalgamated these into a single ‘encyclopedia’ and added entries that cover the period between 2007-2020. The process of gathering Brent’s musical heritage is an ongoing task - there are many incomplete entries and gaps. If you would like to add to, or alter, an entry please send an email to [email protected] 3 4 4 HERO An influential group made up of Dego and Mark Mac, who act as the creative force; Gus Lawrence and Ian Bardouille take care of business. -

Advocate, Fall 2016, Vol. 28, No. 1

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works The Advocate Archives and Special Collections Fall 2016 Advocate, Fall 2016, Vol. 28, No. 1 How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_advocate/22 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] VolumeVolume 28 27 Fall Spring no. 1n. 2016 2 2016 www.GCadvocate.comwww.GCadvocate.com [email protected]@cunydsc.org Donald Trump and the Death Rattle of Liberal Civility pg. 31 Stranger in my Skin: Racial (un)belonging in the US pg. 18 Gil Bruvel, Dichotomy, Stainless Steel sculpture editorial The Difficulty of www.GCadvocate.com Making a Voting Decision [email protected] Contents Who to vote for in the upcoming election? That is be able to keep calm as most of us have been doing? the question. In past elections, the most important Or will I punch back if I am hit—sweetly punch back things that influenced how I vetted presidential can- in the tradition of the ancestors who recognized the EDITORIAL FEATURES didates included their positions on wars, national need to deploy counter strategies that have given me security, economy, the LGBTQ community, and their the liberties I cherish today. Indeed, how powerfully The Difficulty of Stranger in my Skin: plans for developing regions like the Caribbean, where will I punch back with fists, body, talk, and silence until Making a Voting Racial (un)belonging I am from.