The Carter Center Explosive Weapons Use in Syria, Report 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SYRIAN ARAB REPUBLIC IDP Movements December 2020 IDP (Wos) Task Force

SYRIAN ARAB REPUBLIC IDP Movements December 2020 IDP (WoS) Task Force December 2020 updates Governorate summary 19K In December 2020, the humanitarian community tracked some 43,000 IDP Aleppo 17K movements across Syria, similar to numbers tracked in November. As in 25K preceding months, most IDP movements were concentrated in northwest 21K Idleb 13K Syria, with 92 percent occurring within and between Aleppo and Idleb 15K governorates. 800 Ar-Raqqa 800 At the sub-district level, Dana in Idleb governorate and Ghandorah, Bulbul and 800 Sharan in Aleppo governorate each received around 2,800 IDP movements in 443 Lattakia 380 December. Afrin sub-district in Aleppo governorate received around 2,700 830 movements while Maaret Tamsrin sub-district in Idleb governorate and Raju 320 Tartous 230 71% sub-district in Aleppo governorate each received some 2,500 IDP movements. 611 of IDP arrivals At the community level, Tal Aghbar - Tal Elagher community in Aleppo 438 occurred within Hama 43 governorate received the largest number of displaced people, with around 350 governorate 2,000 movements in December, followed by some 1,000 IDP movements 245 received by Afrin community in Aleppo governorate. Around 800 IDP Homs 105 122 movements were received by Sheikh Bahr community in Aleppo governorate 0 Deir-ez-Zor and Ar-Raqqa city in Ar-Raqqa governorate, and Lattakia city in Lattakia 0 IDPs departure from governorate 290 n governorate, Koknaya community in Idleb governorate and Azaz community (includes displacement from locations within 248 governorate and to outside) in Aleppo governorate each received some 600 IDP movements this month. -

The Potential for an Assad Statelet in Syria

THE POTENTIAL FOR AN ASSAD STATELET IN SYRIA Nicholas A. Heras THE POTENTIAL FOR AN ASSAD STATELET IN SYRIA Nicholas A. Heras policy focus 132 | december 2013 the washington institute for near east policy www.washingtoninstitute.org The opinions expressed in this Policy Focus are those of the author and not necessar- ily those of The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, its Board of Trustees, or its Board of Advisors. MAPS Fig. 1 based on map designed by W.D. Langeraar of Michael Moran & Associates that incorporates data from National Geographic, Esri, DeLorme, NAVTEQ, UNEP- WCMC, USGS, NASA, ESA, METI, NRCAN, GEBCO, NOAA, and iPC. Figs. 2, 3, and 4: detail from The Tourist Atlas of Syria, Syria Ministry of Tourism, Directorate of Tourist Relations, Damascus. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publica- tion may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. © 2013 by The Washington Institute for Near East Policy The Washington Institute for Near East Policy 1828 L Street NW, Suite 1050 Washington, DC 20036 Cover: Digitally rendered montage incorporating an interior photo of the tomb of Hafez al-Assad and a partial view of the wheel tapestry found in the Sheikh Daher Shrine—a 500-year-old Alawite place of worship situated in an ancient grove of wild oak; both are situated in al-Qurdaha, Syria. Photographs by Andrew Tabler/TWI; design and montage by 1000colors. -

Policy Notes for the Trump Notes Administration the Washington Institute for Near East Policy ■ 2018 ■ Pn55

TRANSITION 2017 POLICYPOLICY NOTES FOR THE TRUMP NOTES ADMINISTRATION THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY ■ 2018 ■ PN55 TUNISIAN FOREIGN FIGHTERS IN IRAQ AND SYRIA AARON Y. ZELIN Tunisia should really open its embassy in Raqqa, not Damascus. That’s where its people are. —ABU KHALED, AN ISLAMIC STATE SPY1 THE PAST FEW YEARS have seen rising interest in foreign fighting as a general phenomenon and in fighters joining jihadist groups in particular. Tunisians figure disproportionately among the foreign jihadist cohort, yet their ubiquity is somewhat confounding. Why Tunisians? This study aims to bring clarity to this question by examining Tunisia’s foreign fighter networks mobilized to Syria and Iraq since 2011, when insurgencies shook those two countries amid the broader Arab Spring uprisings. ©2018 THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY ■ NO. 30 ■ JANUARY 2017 AARON Y. ZELIN Along with seeking to determine what motivated Evolution of Tunisian Participation these individuals, it endeavors to reconcile estimated in the Iraq Jihad numbers of Tunisians who actually traveled, who were killed in theater, and who returned home. The find- Although the involvement of Tunisians in foreign jihad ings are based on a wide range of sources in multiple campaigns predates the 2003 Iraq war, that conflict languages as well as data sets created by the author inspired a new generation of recruits whose effects since 2011. Another way of framing the discussion will lasted into the aftermath of the Tunisian revolution. center on Tunisians who participated in the jihad fol- These individuals fought in groups such as Abu Musab lowing the 2003 U.S. -

A Case Study on Demographic Engineering in Syria No Return to Homs a Case Study on Demographic Engineering in Syria

No Return to Homs A case study on demographic engineering in Syria No Return to Homs A case study on demographic engineering in Syria Colophon ISBN/EAN: 978-94-92487-09-4 NUR 689 PAX serial number: PAX/2017/01 Cover photo: Bab Hood, Homs, 21 December 2013 by Young Homsi Lens About PAX PAX works with committed citizens and partners to protect civilians against acts of war, to end armed violence, and to build just peace. PAX operates independently of political interests. www.paxforpeace.nl / P.O. Box 19318 / 3501 DH Utrecht, The Netherlands / [email protected] About TSI The Syria Institute (TSI) is an independent, non-profit, non-partisan research organization based in Washington, DC. TSI seeks to address the information and understanding gaps that to hinder effective policymaking and drive public reaction to the ongoing Syria crisis. We do this by producing timely, high quality, accessible, data-driven research, analysis, and policy options that empower decision-makers and advance the public’s understanding. To learn more visit www.syriainstitute.org or contact TSI at [email protected]. Executive Summary 8 Table of Contents Introduction 12 Methodology 13 Challenges 14 Homs 16 Country Context 16 Pre-War Homs 17 Protest & Violence 20 Displacement 24 Population Transfers 27 The Aftermath 30 The UN, Rehabilitation, and the Rights of the Displaced 32 Discussion 34 Legal and Bureaucratic Justifications 38 On Returning 39 International Law 47 Conclusion 48 Recommendations 49 Index of Maps & Graphics Map 1: Syria 17 Map 2: Homs city at the start of 2012 22 Map 3: Homs city depopulation patterns in mid-2012 25 Map 4: Stages of the siege of Homs city, 2012-2014 27 Map 5: Damage assessment showing targeted destruction of Homs city, 2014 31 Graphic 1: Key Events from 2011-2012 21 Graphic 2: Key Events from 2012-2014 26 This report was prepared by The Syria Institute with support from the PAX team. -

Torture Methods the Syrian Regime Continues to Practice in Its Detention Centers and Military Hospitals

Documentation of 72 Torture Methods the Syrian Regime Continues to Practice in Its Detention Centers and Military Hospitals Identifying 801 Individuals Who Appeared in Caesar Photographs, the US Congress Must Pass the Caesar Act to Provide Accountability Monday, October 21, 2019 1 snhr [email protected] www.sn4hr.org R190912 The Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR), founded in June 2011, is a non-governmental, independent group that is considered a primary source for the OHCHR on all death toll-related analyses in Syria. Contents I. Introduction and methodology of the report II. The Syrian Network for Human Rights’ cooperation with the UN Rapporteur on deaths due to Torture III. The toll of victims who died due to torture according to the SNHR’s database IV. The most notable methods of torture in the Syrian regime’s detention centers Physical torture Health neglect, conditions of detention and deprivation Sexual violence Psychological torture and humiliation of human dignity Forced labor Torture in military hospitals Separation V. New identification of 29 individuals who appeared in Caesar photographs leaked from military hospitals VI. Examples of individuals shown in Caesar photographs who we were able to identify VII. Various testimonies of torture incidents by survivors of the Syrian regime’s detention centers VIII. The most notable individuals responsible for torture in the Syrian regime’s detention centers according to the SNHR’s database IX. Conclusions and recommendations 1 snhr [email protected] www.sn4hr.org I. Introduction and methodology of the report: Hundreds of thousands of Syrians have been subjected to abduction (detention) by Syrian Regime forces; according to the Syrian Network for Human Rights’ (SNHR) database, at least 130,000 individuals are still detained or forcibly disappeared by the Syrian regime since the start of the popular uprising for democracy in Syria in March 2011. -

Situation Report: WHO Syria, Week 19-20, 2019

WHO Syria: SITUATION REPORT Weeks 32 – 33 (2 – 15 August), 2019 I. General Development, Political and Security Situation (22 June - 4 July), 2019 The security situation in the country remains volatile and unstable. The main hot spots remain Daraa, Al- Hassakah, Deir Ezzor, Latakia, Hama, Aleppo and Idlib governorates. The security situation in Idlib and North rural Hama witnessed a notable escalation in the military activities between SAA and NSAGs, with SAA advancement in the area. Syrian government forces, supported by fighters from allied popular defense groups, have taken control of a number of villages in the southern countryside of the northwestern province of Idlib, reaching the outskirts of a major stronghold of foreign-sponsored Takfiri militants there The Southern area, particularly in Daraa Governorate, experienced multiple attacks targeting SAA soldiers . The security situation in the Central area remains tense and affected by the ongoing armed conflict in North rural Hama. The exchange of shelling between SAA and NSAGs witnessed a notable increase resulting in a high number of casualties among civilians. The threat of ERWs, UXOs and Landmines is still of concern in the central area. Two children were killed, and three others were seriously injured as a result of a landmine explosion in Hawsh Haju town of North rural Homs. The general situation in the coastal area is likely to remain calm. However, SAA military operations are expected to continue in North rural Latakia and asymmetric attacks in the form of IEDs, PBIEDs, and VBIEDs cannot be ruled out. II. Key Health Issues Response to Al Hol camp: The Security situation is still considered as unstable inside the camp due to the stress caused by the deplorable and unbearable living conditions the inhabitants of the camp have been experiencing . -

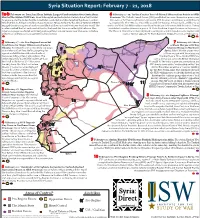

Syria SITREP Map 07

Syria Situation Report: February 7 - 21, 2018 1a-b February 10: Israel and Iran Initiate Largest Confrontation Over Syria Since 6 February 9 - 15: Turkey Creates Two Additional Observation Points in Idlib Start of the Syrian Civil War: Israel intercepted and destroyed an Iranian drone that violated Province: The Turkish Armed Forces (TSK) established two new observation points near its airspace over the Golan Heights. Israel later conducted airstrikes targeting the drone’s control the towns of Tal Tuqan and Surman in Eastern Idlib Province on February 9 and February vehicle at the T4 Airbase in Eastern Homs Province. Syrian Surface-to-Air Missile Systems (SAMS) 15, respectively. The TSK also reportedly scouted the Taftanaz Airbase north of Idlib City as engaged the returning aircraft and successfully shot down an Israeli F-16 over Northern Israel. The well as the Wadi Deif Military Base near Khan Sheikhoun in Southern Idlib Province. Turkey incident marked the first such combat loss for the Israeli Air Force since the 1982 Lebanon War. established a similar observation post at Al-Eis in Southern Aleppo Province on February 5. Israel in response conducted airstrikes targeting at least a dozen targets near Damascus including The Russian Armed Forces later deployed a contingent of military police to the regime-held at least four military positions operated by Iran in Syria. town of Hadher opposite Al-Eis in Southern Aleppo Province on February 14. 2 February 17 - 20: Pro-Regime Forces Set Qamishli 7 February 18: Ahrar Conditions for Major Offensive in Eastern a-Sham Merges with Key Ghouta: Pro-regime forces intensified a campaign 9 Islamist Group in Northern of airstrikes and artillery shelling targeting the 8 Syria: Salafi-Jihadist group Ahrar opposition-held Eastern Ghouta suburbs of Al-Hasakah a-Sham merged with Islamist group Damascus, killing at least 250 civilians. -

REGIONAL ANALYSIS SYRIA Received Little Or No Humanitarian Assistance in More Than 10 Months

currently estimated to be living in hard to reach or besieged areas, having REGIONAL ANALYSIS SYRIA received little or no humanitarian assistance in more than 10 months. 07 February 2014 Humanitarian conditions in Yarmouk camp continued to worsen with 70 reported deaths in the last 4 months due to the shortage of food and medical supplies. Local negotiations succeeded in facilitating limited amounts of humanitarian Part I – Syria assistance to besieged areas, including Yarmouk, Modamiyet Elsham and Content Part I Barzeh neighbourhoods in Damascus although the aid provided was deeply This Regional Analysis of the Syria conflict (RAS) is an update of the December RAS and seeks to Overview inadequate. How to use the RAS? bring together information from all sources in the The spread of polio remains a major concern. Since first confirmed in October region and provide holistic analysis of the overall Possible developments Syria crisis. In addition, this report highlights the Map - Latest developments 2013, a total of 93 polio cases have been reported; the most recent case in Al key humanitarian developments in 2013. While Key events 2013 Hasakeh in January. In January 2014 1.2 million children across Aleppo, Al Part I focuses on the situation within Syria, Part II Information gaps and data limitations Hasakeh, Ar-Raqqa, Deir-ez-Zor, Hama, Idleb and Lattakia were vaccinated covers the impact of the crisis on neighbouring Operational constraints achieving an estimated 88% coverage. The overall health situation is one of the countries. More information on how to use this Humanitarian profile document can be found on page 2. -

Highlights Situation Overview

Syria Crisis Bi-Weekly Situation Report No. 05 (as of 22 May 2016) This report is produced by the OCHA Syria Crisis offices in Syria, Turkey and Jordan. It covers the period from 7-22 May 2016. The next report will be issued in the second week of June. Highlights Rising prices of fuel and basic food items impacting upon health and nutritional status of Syrians in several governorates Children and youth continue to suffer disproportionately on frontlines Five inter-agency convoys reach over 50,000 people in hard-to-reach and besieged areas of Damascus, Rural Damascus and Homs Seven cross-border consignments delivered from Turkey with aid for 631,150 people in northern Syria Millions of people continued to be reached from inside Syria through the regular programme Heightened fighting displaces thousands in Ar- Raqqa and Ghouta Resumed airstrikes on Dar’a prompting displacement 13.5 M 13.5 M 6.5 M 4.8 M People in Need Targeted for assistance Internally displaced Refugees in neighbouring countries Situation Overview The reporting period was characterised by evolving security and conflict dynamics which have had largely negative implications for the protection of civilian populations and humanitarian access within locations across the country. Despite reaffirmation of a commitment to the country-wide cessation of hostilities agreement in Aleppo, and a brief reduction in fighting witnessed in Aleppo city, civilians continued to be exposed to both indiscriminate attacks and deprivation as parties to the conflict blocked access routes to Aleppo city and between cities and residential areas throughout northern governorates. Consequently, prices for fuel, essential food items and water surged in several locations as supply was threatened and production became non-viable, with implications for both food and water security of affected populations. -

Aleppo Governorate

Suruc ﺳورودج Oguzeli d أوﻏوﻠﯾزﯾﮫ d Şanlıurfa أوﻓﺔر DOWNLOAD MAP ZobarZorabi - C1948 اﻟﺠﻤﻬﻮرﻳﺔ اﻟﻌﺮﺑﻴﺔ اﻟﺴــﻮرﻳﺔ SYRIAN ARAB REPUBLIC Estiqama زوﺑﺎر _زوراﺑﻲ - BabnBoban d C1975 C1966 d AinAlArab اﻻﻘﻣﺳﺎﺔﺗﻛ_ورﺑﺎ d C1946 ﺑﺎﺑﺎن _ﺑوﺑﺎن OrubaKor - Ali d ﻌﻟﻋرﯾ انب -Musabeyli Susan Sus C1956 MorshedMorshed Binar d d Reference Map C1980 Minasﻣوﺳﻠﺎﯾﺑﯾﮫ BijanTramk ﻋروﺑﺔﻛﻠ_ﻲو ﻋر ALEPPO GOVERNORATE d C1987 d C6340 Sharan ﺻو ص _ﺻوﺻﺎن C1961 ﻣرﻣ ﺷردﻧ ﺷﺑﺎدﯾر d - C1940 NafKarabnafKarab ﻧﺎﻣﯾس UpperQurran d Scan it! Navigate! d ﺑﯾﺟﺎن _ﺗﻣرك BigDuwara Jraqli - Qola d C1988 ﺷران with QR reader App with Avenza PDF C2021 d C1998 d Gh arib ﻧﺎﻛ رف بﻛ_ﻧرﺎﺑف C1990 AziziyehMom - anAzu Kalmad FirazdaqArsalan - Tash ﻗﻧﻲﻗﻓرﺎاو ن Maps App ﺧﺮﻳــﻄﺔ ﻣﺮﺟــﻌﻴﺔ d TalHajib d C6341 C1943 ﻗوﻻ ﻟداوﻛاﻟﺑﯾ راةرة _ﻠﻲﺟﺎﻗر Gaziantep d d d C1974 C1954 ﻣﺤــــﺎﻓـﻈـﺔ ﺣﻠﺐ ﻏرﯾ ب d C1949 d ﻣﻠدﻛ ﺗ لﺣﺎ ﺟ بd ﻔﻟرزادق_أرﺳﻼ طﺎن ش d ﻋزﯾزﯾﺔﻣ_ﻣوﺎ ﻋنزو Polateli Jebnet Shakriyeh- UpperJbeilehQorrat - Quri d KharabNas Karkamis C1995 d Mashko C1972 ﺑوﻠﻻﯾﺗﯾﮫ -QantarraQantaret Kikan ﻏﺎﻧﺗز ﺎﻋيب d s C1994 d Qarruf YadiHbabQawi - KorbinarNabaa - BigEin Elbat C1967ﺟlu/ﻠabرا aJrﺑس C1936 ﻧﻲﻗﻗﻓﻗﺎوو ﻠ_رﺟﺑﺔةرﯾي ﻧﺟﺔﺑ ﻛﺎﻛﻣرﺎﯾ س ﺧرﻧاﺎ بس d C1985 C1976 C1962 C1957 ﻟﺷاﻛﺎرﯾﺔﻣ_ﻛﺷو d d ﻧطﻘﻧرطﻟﻛةﻛﻗ ﯾﺎرا_ةن KherbetAtu d ﻛﺎ isﻛﻣ/رﺎﯾ amسKark ﻛ ﻟﻋﺑﯾﺑﯾ طانر KharanKort ﻧﻌﺑﺔﻟﻛ_اورﻧﺑﺎﯾر ﻟﺣاﺑﺎ ب ﯾﻗ_دو يي ﻗروف Jarablus Shankal ] C2001 d d d JilJilak d MeidanEkbis Kusan C2227 ShehamaBandar - C1968 C1482 d C2012 C1964 ﺧر ﺑﻋطﺔو C1488 C1490d d ﺧراﻛ وبرت d UpperDar Elbaz BigMazraet Sofi ﺟﻠراﺑس - HjeilehJrables ﺟﯾل _ﻠكﺟﯾ MaydanKork - Kitan -

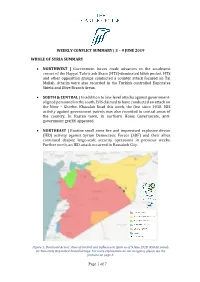

Weekly Conflict Summary | 3 – 9 June 2019

WEEKLY CONFLICT SUMMARY | 3 – 9 JUNE 2019 WHOLE OF SYRIA SUMMARY • NORTHWEST | Government forces made advances in the southwest corner of the Hayyat Tahrir ash Sham (HTS)-dominated Idleb pocket. HTS and other opposition groups conducted a counter attack focused on Tal Mallah. Attacks were also recorded in the Turkish-controlled Euphrates Shield and Olive Branch Areas. • SOUTH & CENTRAL | In addition to low-level attacks against government- aligned personnel in the south, ISIS claimed to have conducted an attack on the Nimr – Gherbet Khazalah Road this week, the first since 2018. ISIS activity against government patrols was also recorded in central areas of the country. In Rastan town, in northern Homs Governorate, anti- government graffiti appeared. • NORTHEAST | Routine small arms fire and improvised explosive device (IED) activity against Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) and their allies continued despite large-scale security operations in previous weeks. Further north, an IED attack occurred in Hassakeh City. Figure 1: Dominant Actors’ Area of Control and Influence in Syria as of 9 June 2019. NSOAG stands for Non-state Organized Armed Groups. For more explanation on our mapping, please see the footnote on page 2. Page 1 of 7 WEEKLY CONFLICT SUMMARY | 3 – 9 JUNE 2019 NORTHWEST SYRIA1 This week, Government of Syria (GOS) forces made advances in the southwest corner of the Hayyat Tahrir ash Sham (HTS)-dominated Idleb enclave. On 3 June, GOS Tiger Forces captured al Qasabieyh town to the north of Kafr Nabuda, before turning west and taking Qurutiyah village a day later. Currently, fighting is concentrated around Qirouta village. However, late on 5 June, HTS and the Turkish-Backed National Liberation Front (NLF) launched a major counter offensive south of Kurnaz town after an IED detonated at a fortified government location. -

Full Profile (2014)

Al-Mawred Al-Thaqafi (Culture Resource) Organization launched in 2009 a regional initiative aims to identify the main features of cultural policy in Arab countries. The ultimate goal is to build a Knowledge Base that supports cultural planning and collaboration in the region, as well as propose mechanisms to develop cultural work in Arab countries. First stage of the project targeted preliminary surveys of policies, legislations, and practices that guide cultural work in eight Arab countries: Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, Palestine, Egypt, Algeria, Tunisia, and Morocco. The process of Monitoring was conducted in the period between May 2009 and January 2010 by Arab researchers from all eight countries, and thus “Ettijahat. Independent culture” as the regional coordinator of the project developed the surveys and updated its information and data through specialized researchers who reviewed the information and amended it based on the most recent developments in the cultural scene. The study has been completed according to the Compendium model which is adopted in study about cultural policies around the world. Research is divided into the following: 1- Cultural context from a social and historical perspective. 2- Administrative Subsidiarity and decision-making. 3- General objectives and principles of cultural policies. 4- Current topics debated in cultural policy development. 5- Main legal texts in the cultural field. 6- Financing of culture events and institutions. 7- Cultural institutions and new partnerships. 8- Supporting creativity and collaborations. This survey has been conducted in 2009 and 2010 by the researchers Rana Yazeji and Reem Al Khateeb. The original material of the current survey is found below in black.