9.50D Bullmastiff

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Breed Name # Cavalier King Charles Spaniel LITTLE GUY Bernese

breed name # Cavalier King Charles Spaniel LITTLE GUY Bernese Mountain Dog AARGAU Beagle ABBEY English Springer Spaniel ABBEY Wheaten Terrier ABBEY Golden Doodle ABBIE Bichon Frise ABBY Cocker Spaniel ABBY Golden Retriever ABBY Golden Retriever ABBY Labrador Retriever ABBY Labrador Retriever ABBY Miniature Poodle ABBY 11 Nova Scotia DuckTolling Retriever ABE Standard Poodle ABIGAIL Beagle ACE Boxer ACHILLES Gordon Setter ADDIE Miniature Schnauzer ADDIE Australian Terrier ADDY Golden Retriever ADELAIDE Portuguese Water Dog AHAB Cockapoo AIMEE Labrador Retriever AJAX Dachshund ALBERT Labrador Retriever ALBERT Havanese ALBIE Golden Retriever ALEXIS Yorkshire Terrier ALEXIS Bulldog ALFIE Collie ALFIE Golden Retriever ALFIE Labradoodle ALFIE Bichon Frise ALFRED Chihuahua ALI Cockapoo ALLEGRO Border Collie ALLIE Coonhound ALY Mix AMBER Labrador Retriever AMELIA Labrador Retriever AMOS Old English Sheepdog AMY aBreedDesc aName Labrador Retriever ANDRE Golden Retriever ANDY Mix ANDY Chihuahua ANGEL Jack Russell Terrier ANGEL Labrador Retriever ANGEL Poodle ANGELA Nova Scotia DuckTolling Retriever ANGIE Yorkshire Terrier ANGIE Labrador Retriever ANGUS Maltese ANJA American Cocker Spaniel ANNABEL Corgi ANNIE Golden Retriever ANNIE Golden Retriever ANNIE Mix ANNIE Schnoodle ANNIE Welsh Corgi ANNIE Brittany Spaniel ANNIKA Bulldog APHRODITE Pug APOLLO Australian Terrier APPLE Mixed Breed APRIL Mixed Breed APRIL Labrador Retriever ARCHER Boston Terrier ARCHIE Yorkshire Terrier ARCHIE Pug ARES Golden Retriever ARGOS Labrador Retriever ARGUS Bichon Frise ARLO Golden Doodle ASTRO German Shepherd Dog ATHENA Golden Retriever ATTICUS Yorkshire Terrier ATTY Labradoodle AUBREE Golden Doodle AUDREY Labradoodle AUGIE Bichon Frise AUGUSTUS Cockapoo AUGUSTUS Labrador Retriever AVA Labrador Retriever AVERY Labrador Retriever AVON Labrador Retriever AWIXA Corgi AXEL Dachshund AXEL Labrador Retriever AXEL German Shepherd Dog AYANA West Highland White Terrier B.J. -

Molosser Dogs: Content / Breed Profiles / American Bulldog

Molosser Dogs: Content / Breed Profiles / Americ... http://molosserdogs.com/e107_plugins/content/c... BREEDERS DIRECTORY MOLOSSER GROUP MUST HAVE PETS SUPPLIES AUCTION CONTACT US HOME MEDIA DISCUSS RESOURCES BREEDS SUBMIT ACCOUNT STORE Search Molosser Dogs show overview of sort by ... search by keyword search Search breadcrumb Welcome home | content | Breed Profiles | American Bulldog Username: American Bulldog Password: on Saturday 04 July 2009 by admin Login in Breed Profiles comments: 3 Remember me hits: 1786 10.0 - 3 votes - [ Signup ] [ Forgot password? ] [ Resend Activation Email ] Originating in 1700\'s America, the Old Country Bulldogge was developed from the original British and Irish bulldog variety, as well as other European working dogs of the Bullenbeisser and Alaunt ancestry. Many fanciers believe that the original White English Bulldogge survived in America, where Latest Comments it became known as the American Pit Bulldog, Old Southern White Bulldogge and Alabama Bulldog, among other names. A few regional types were established, with the most popular dogs found in the South, where the famous large white [content] Neapolitan Mastiff plantation bulldogges were the most valued. Some bloodlines were crossed with Irish and Posted by troylin on 30 Jan : English pit-fighting dogs influenced with English White Terrier blood, resulting in the larger 18:20 strains of the American Pit Bull Terrier, as well as the smaller variety of the American Bulldog. Does anyone breed ne [ more ... Although there were quite a few "bulldogges" developed in America, the modern American Bulldog breed is separately recognized. ] Unlike most bully breeds, this lovely bulldog's main role wasn't that of a fighting dog, but rather of a companion and worker. -

The Origin of the Tibetan Mastiff and Species Identification of Canis Based on Mitochondrial Cytochrome C Oxidase Subunit I (COI) Gene and COI Barcoding

Animal (2011), 5:12, pp 1868–1873 & The Animal Consortium 2011 animal doi:10.1017/S1751731111001042 The origin of the Tibetan Mastiff and species identification of Canis based on mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (COI) gene and COI barcoding - - Y. Li 1, X. Zhao2,Z.Pan1, Z. Xie1, H. Liu1,Y.Xu1 and Q. Li1 1College of Animal Science and Technology, Nanjing Agricultural University, Nanjing 210095, China; 2College of Animal Science and Technology, State Key Laboratory for Agrobiotechnology, China Agricultural University, Beijing 100094, China (Received 28 December 2010; Accepted 24 April 2011; First published online 11 July 2011) DNA barcoding is an effective technique to identify species and analyze phylogenesis and evolution. However, research on and application of DNA barcoding in Canis have not been carried out. In this study, we analyzed two species of Canis, Canis lupus (n 5 115) and Canis latrans (n 5 4), using the cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (COI) gene (1545 bp) and COI barcoding (648 bp DNA sequence of the COI gene). The results showed that the COI gene, as the moderate variant sequence, applied to the analysis of the phylogenesis of Canis members, and COI barcoding applied to species identification of Canis members. Phylogenetic trees and networks showed that domestic dogs had four maternal origins (A to D) and that the Tibetan Mastiff originated from Clade A; this result supports the theory of an East Asian origin of domestic dogs. Clustering analysis and networking revealed the presence of a closer relative between the Tibetan Mastiff and the Old English sheepdog, Newfoundland, Rottweiler and Saint Bernard, which confirms that many well-known large breed dogs in the world, such as the Old English sheepdog, may have the same blood lineage as that of the Tibetan Mastiff. -

Quiz Sheets BDB JWB 0513.Indd

2. A-Z Dog Breeds Quiz Write one breed of dog for each letter of the alphabet and receive one point for each correct answer. There’s an extra five points on offer for those that can find correct answers for Q, U, X and Z! A N B O C P D Q E R F S G T H U I V J W K X L Y M Z Dogs for the Disabled The Frances Hay Centre, Blacklocks Hill, Banbury, Oxon, OX17 2BS Tel: 01295 252600 www.dogsforthedisabled.org supporting Registered Charity No. 1092960 (England & Wales) Registered in Scotland: SCO 39828 ANSWERS 2. A-Z Dog Breeds Quiz Write a breed of dog for each letter of the alphabet (one point each). Additional five points each if you get the correct answers for letters Q, U, X or Z. Or two points each for the best imaginative breed you come up with. A. Curly-coated Retriever I. P. Tibetan Spaniel Affenpinscher Cuvac Ibizan Hound Papillon Tibetan TerrieR Afghan Hound Irish Terrier Parson Russell Terrier Airedale Terrier D Irish Setter Pekingese U. Akita Inu Dachshund Irish Water Spaniel Pembroke Corgi No Breed Found Alaskan Husky Dalmatian Irish Wolfhound Peruvian Hairless Dog Alaskan Malamute Dandie Dinmont Terrier Italian Greyhound Pharaoh Hound V. Alsatian Danish Chicken Dog Italian Spinone Pointer Valley Bulldog American Bulldog Danish Mastiff Pomeranian Vanguard Bulldog American Cocker Deutsche Dogge J. Portugese Water Dog Victorian Bulldog Spaniel Dingo Jack Russel Terrier Poodle Villano de Las American Eskimo Dog Doberman Japanese Akita Pug Encartaciones American Pit Bull Terrier Dogo Argentino Japanese Chin Puli Vizsla Anatolian Shepherd Dogue de Bordeaux Jindo Pumi Volpino Italiano Dog Vucciriscu Appenzeller Moutain E. -

Ian Macinnes 1 He Hath Been Brought up in the Ile

Ian MacInnes MASTIFFS AND SPANIELS: GENDER AND NATION IN THE ENGLISH DOG He hath been brought up in the Ile of Dogges & can both fawne like a Spaniell, and bite like a Mastive. – Moll Cutpurse In her seminal book on animals in the nineteenth century, The Animal Estate, Harriet Ritvo postulates that “animal-related discourse has often functioned as an extended, if unacknowledged metonymy, offering participants a concealed forum for the expression of opinions and worries imported from the human cultural arena."1 Most recent work on animals in early modern England has concentrated on the degree to which such opinions and worries concern the animal-human boundary and the question of what it means to be human.2 This large issue was certainly as much in question for the early moderns as it has been since, but it can tend to obscure some of the more unique deployment of animals at work in the period. Animal discourse may fit into larger philosophical or theological ideas about humanity but actual animals could also be deployed, consciously and more or less systematically, as a vehicle for expressing attitudes specific to a place and time. In what follows I explore one such metonymy in early modern England. It is a metonymy that links English dogs with early modern English attitudes toward national character, attitudes in which hopes and anxieties about nation and gender coincide. By the end of the sixteenth century England was already considered to have a unique relationship with dogs, and England ’s nascent national identity was already connected with the dogs for which it was famous throughout Europe. -

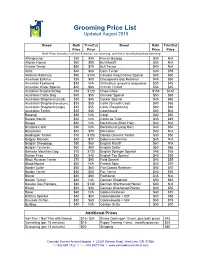

Grooming Price List Updated August 2016

Grooming Price List Updated August 2016 Breed Bath Trim/Cut Breed Bath Trim/Cut Price Price Price Price Bath Price includes: nail trim & dremel, ear cleaning, and minor face/feet/sanitary trimming Affenpincher $30 $45 French Bulldog $30 N/A Afghan Hound $60 $90 Bull Mastiff $55 N/A Airdale Terrier $50 $70 Bull Terrier $40 N/A Akita $40 $60 Cairn Terrier $30 $55 Alaskan Malamute $90 $140 Cavalier King Charles Spaniel $40 $60 American Eskimo $35 $60 Chesapeake Bay Retriever $45 $65 American Foxhound $30 N/A Chihuahua (smooth & longcoated) $30 $45 American Water Spaniel $40 $60 Chinese Crested $33 $45 Anatolian Shepherd Dog $70 $120 Chow Chow $100 $140 Australian Cattle Dog $45 $55 Clumber Spaniel $50 $65 Australian Shepherd (small) $30 $45 Cocker Spaniel $45 $65 Australian Shepherd (medium) $35 $50 Collie (Smooth Coat) $40 $65 Australian Shepherd (large) $40 $55 Collie (RoughCoat) $60 $80 Australian Terrier $30 $45 Coonhound $40 N/A Basengi $35 N/A Corgi $40 $50 Basset Hound $40 N/A Coton de Tular $35 $45 Beagle $30 N/A Dachshund (Short Hair) $40 N/A Bearded Collie $30 N/A Dachshund (Long Hair) $40 $50 Beauceron $40 $70 Dalmation $40 N/A Bedlington Terrier $70 $100 Dandie Dinmont Terrier $30 $50 Belgian Malinois $40 $70 Doberman Pincher $45 N/A Belgian Sheepdog $50 $80 English Mastiff $60 N/A Belgian Tervwren $50 $80 English Setter $50 $65 Bernese Mountain Dog $70 $120 English Springer Spaniel $45 $65 Bichon Frise $35 $45 English Toy Spaniel $40 $55 Black Russian Terrier $70 $90 Field Spaniel $40 $55 Blood Hound $50 N/A Finnish Spitz $40 -

Animalfolksmn.Org

ANIMAL FOLKS MN www.animalfolksmn.org SOME DOG BREEDS PRODUCED AND/OR SOLD BY MN BREEDER KATHY BAUCK as reported on Minnesota Certificates of Veterinary Inspection Black Labrador Basset Yellow Labrador Pug Labrador x Poodle (Labradoodle) Pug x Brussels English Bulldog Pug x Beagle (Puggle) Victorian Bulldog Pug x Jack Russell French Bulldog Jack Russell American Bulldog Jack Russell x Westie Oldie x American Bulldog Papillon Oldie x English Bulldog Pomeranian Shiba x American Bulldog King Charles x Havanese Mastiff x American Bulldog King Charles x Poodle English Bulldog x Beagle (Bullgle) King Charles x Yorkie French Bulldog x Boston Terrier King Charles x Cocker Beagle King Charles x Bichon Beagle x Shar pei Doxie x Tib Terrier Beagle x Sheltie Neopolitan Mastiff Bichon Frise English Mastiff Bichon x Cocker Dane x Mastiff Bichon x Havanese Ch. Shar pei Bichon x Poodle Dachshund Bichon x Westie Doxie x Yorkie Bichon x Sheba Maltese Bichon x Lhasa Maltese x Cocker Bichon x Cairn Maltese x Havanese German Shepherd Maltese x Yorkie Golden Retriever Maltese x Pekingese Golden x German Shepherd Maltese x Pom Golden x Poodle (Goldendoodle) Maltese x King Charles Cocker Spaniel Maltese x Doxie Shih tzu Maltese x Lhasa Shih tzu x Maltese Morkie Shih tzu x Pom Silky Terrier Shih tzu x Havanese Yorkshire Terrier Shih tzu x Bichon Shiba x Cairn Terrier Shih tzu x Yorkie Yorkie x Cairn Terrier Shih tzu x Poodle Poodle x Cairn Terrier Shih tzu x Pekingese Yorkie x Silky Terrier Lhasa Apso Sheltie Lhasa x Havanese Shiba Inu Poodle Siberian Husky Pom x Poodle (Pomapoo) Samoyan Husky Yorkie x Poodle (Yorkapoo) Husky x American Eskimo Cocker x Poodle (Cockapoo) American Eskimo x Shiba Westie x Poodle Pekingese Lhasa x Poodle Chin x Pekingese Cockapoo x Poodle Chihuahua Boxer Chihuahua x Minpin S.C. -

Domestic Dog Breeding Has Been Practiced for Centuries Across the a History of Dog Breeding Entire Globe

ANCESTRY GREY WOLF TAYMYR WOLF OF THE DOMESTIC DOG: Domestic dog breeding has been practiced for centuries across the A history of dog breeding entire globe. Ancestor wolves, primarily the Grey Wolf and Taymyr Wolf, evolved, migrated, and bred into local breeds specific to areas from ancient wolves to of certain countries. Local breeds, differentiated by the process of evolution an migration with little human intervention, bred into basal present pedigrees breeds. Humans then began to focus these breeds into specified BREED Basal breed, no further breeding Relation by selective Relation by selective BREED Basal breed, additional breeding pedigrees, and over time, became the modern breeds you see Direct Relation breeding breeding through BREED Alive migration BREED Subsequent breed, no further breeding Additional Relation BREED Extinct Relation by Migration BREED Subsequent breed, additional breeding around the world today. This ancestral tree charts the structure from wolf to modern breeds showing overlapping connections between Asia Australia Africa Eurasia Europe North America Central/ South Source: www.pbs.org America evolution, wolf migration, and peoples’ migration. WOLVES & CANIDS ANCIENT BREEDS BASAL BREEDS MODERN BREEDS Predate history 3000-1000 BC 1-1900 AD 1901-PRESENT S G O D N A I L A R T S U A L KELPIE Source: sciencemag.org A C Many iterations of dingo-type dogs have been found in the aborigine cave paintings of Australia. However, many O of the uniquely Australian breeds were created by the L migration of European dogs by way of their owners. STUMPY TAIL CATTLE DOG Because of this, many Australian dogs are more closely related to European breeds than any original Australian breeds. -

Retinal Disorders in Border Collies Gregory M

Retinal Disorders in Border Collies Gregory M. Acland, B.V.Sc., DACVO, MRCVS The retina is the specialized part of the eye that contains the nerve cells that make vision possible. Traditionally, if one compares an eye to a camera then the retina corresponds to the film. This is a useful mental image because one immediately understands that the film cannot work if the camera itself is broken or has the lens cap on; but the camera is totally useless without film in it. A better analogy today would be to compare the eye to a video camera, and the retina to the silicon chips inside that convert light into an electrical signal that can be sent to a video tape recorder or TV monitor. Because the normal eye is transparent, it is possible to look inside with a special instrument called an ophthalmoscope, and see whether the retina is healthy or not. Retinal diseases destroy its nerve cells, producing either partial or total blindness, in people, dogs, and other animals. In a working dog such as the Border Collie the risk of vision loss, from retinal or any other disease. is particularly threatening. Retinal disease, like diseases elsewhere in the body, can be caused by many agents, including infections, parasites, trauma (that is injury from physical causes), nutrition (diet), and hereditary factors (genes). Also as in diseases affecting other parts of the body, some retinal diseases have known causes, but many others are poorly understood at best. The most important thing that sets retinal disease apart from disease elsewhere in the body is the limited ability of the retina to respond to injury without impairing its own function. -

Curs, Conquest, and Cullings: Dogs As Symbols and Actors in the Conquest of New England”

“Curs, Conquest, and Cullings: Dogs as Symbols and Actors in the Conquest of New England” [Note: This paper represents research in progress. Please do not cite. I am happy to respond to correspondence sent to [email protected]] By Strother E. Roberts Assistant Professor History Department Bowdoin College At The 24th Annual Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture Williamsburg, Virginia June 14th-17th, 2018 1 In the year 1600, New England was home to tens of thousands of indigenous dogs, perhaps as many as 100,000 domesticated canines or more. This population suffered severe losses over the following two centuries. Indeed, all evidence, both historical and that gathered by genetic researchers, suggests the extinction of New England’s indigenous dogs probably occurred sometime in the nineteenth century.1 Of course, the possibility that some descendants of this original population of New England dogs still survive cannot fully be ruled out. It is entirely possible that some portion of the indigenous genome has survived through interbreeding with dogs of primarily European and Asian heritage. But at the very least, the past four centuries have seem the creation of a canine “neo-Europe,” to borrow a term that Alfred Crosby coined to refer to regions outside Europe where the genetic descendants of Europeans now form a majority of the population. The story of how this came to be true is one of tragedy – for both dogs and humans alike. European dogs did not simply out-compete New England’s indigenous dogs, except, perhaps, in the competition for a place in the hearts of the Euro-Americans who came to politically dominate the region. -

Dog Breeds Volume 5

Dog Breeds - Volume 5 A Wikipedia Compilation by Michael A. Linton Contents 1 Russell Terrier 1 1.1 History ................................................. 1 1.1.1 Breed development in England and Australia ........................ 1 1.1.2 The Russell Terrier in the U.S.A. .............................. 2 1.1.3 More ............................................. 2 1.2 References ............................................... 2 1.3 External links ............................................. 3 2 Saarloos wolfdog 4 2.1 History ................................................. 4 2.2 Size and appearance .......................................... 4 2.3 See also ................................................ 4 2.4 References ............................................... 4 2.5 External links ............................................. 4 3 Sabueso Español 5 3.1 History ................................................ 5 3.2 Appearance .............................................. 5 3.3 Use .................................................. 7 3.4 Fictional Spanish Hounds ....................................... 8 3.5 References .............................................. 8 3.6 External links ............................................. 8 4 Saint-Usuge Spaniel 9 4.1 History ................................................. 9 4.2 Description .............................................. 9 4.2.1 Temperament ......................................... 10 4.3 References ............................................... 10 4.4 External links -

Dogs of China 6G" Japan in Nature And

" DOGS OF CHINA 6g JAPAN I N N AT UR E AN D AR T . F . OL L IE R V . W . C I L L US TR A TE D N E W YORK F REDER C T E P N Y I K A . S OK S COM A P UBLI SHERS PRE FACE a an eo le HINA and J p , their p p and their customs , have lured the foreigner in his thousands to the making of No writer has many books . , however , thought fit to ‘ ‘ devote much study to their canine racefthough in the Far ’ as East , just in Europe , the dog has been for ages man s chief help and protector ’ d a ’ The rich man s guar ian and the poor m n s friend , ‘ The only creature faithful to the end . T hose who have , in passing , deigned to notice the existence of dogs in the Far East have paused only for brief comment , usually by way of grasping another stick to beat the Celestial for gastronomic eccentricity or superstitious delusions , and have given to the Eastern canine races scarcely the proverbial dog ’ s chance of being considered better than universally mongrel . It is not claimed for the following pages , whose original design included only the smaller races of Eastern dogs , that the they enumerate all existing breeds , or that they deal con i l r clus ve y with any one of them . China alone is a vast count y in which geographical difficulties render comprehensive study fi has dif cult .