9 Chapter Nine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

After the Treaties: a Social, Economic and Demographic History of Maroon Society in Jamaica, 1739-1842

University of Southampton Research Repository Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis and, where applicable, any accompanying data are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis and the accompanying data cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content of the thesis and accompanying research data (where applicable) must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder/s. When referring to this thesis and any accompanying data, full bibliographic details must be given, e.g. Thesis: Author (Year of Submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University Faculty or School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. University of Southampton Department of History After the Treaties: A Social, Economic and Demographic History of Maroon Society in Jamaica, 1739-1842 Michael Sivapragasam A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History June 2018 i ii UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY Doctor of Philosophy After the Treaties: A Social, Economic and Demographic History of Maroon Society in Jamaica, 1739-1842 Michael Sivapragasam This study is built on an investigation of a large number of archival sources, but in particular the Journals and Votes of the House of the Assembly of Jamaica, drawn from resources in Britain and Jamaica. Using data drawn from these primary sources, I assess how the Maroons of Jamaica forged an identity for themselves in the century under slavery following the peace treaties of 1739 and 1740. -

Freedom As Marronage

Freedom as Marronage Freedom as Marronage NEIL ROBERTS The University of Chicago Press Chicago and London Neil Roberts is associate professor of Africana studies and a faculty affiliate in political science at Williams College. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2015 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. Published 2015. Printed in the United States of America 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 1 2 3 4 5 ISBN- 13: 978- 0- 226- 12746- 0 (cloth) ISBN- 13: 978- 0- 226- 20104- 7 (paper) ISBN- 13: 978- 0- 226- 20118- 4 (e- book) DOI: 10.7208/chicago/9780226201184.001.0001 Jacket illustration: LeRoy Clarke, A Prophetic Flaming Forest, oil on canvas, 2003. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Roberts, Neil, 1976– author. Freedom as marronage / Neil Roberts. pages ; cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978- 0- 226- 12746- 0 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 978- 0- 226- 20104- 7 (pbk : alk. paper) — ISBN 978- 0- 226- 20118- 4 (e- book) 1. Maroons. 2. Fugitive slaves—Caribbean Area. 3. Liberty. I. Title. F2191.B55R62 2015 323.1196'0729—dc23 2014020609 o This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48– 1992 (Permanence of Paper). For Karima and Kofi Time would pass, old empires would fall and new ones take their place, the relations of countries and the relations of classes had to change, before I discovered that it is not quality of goods and utility which matter, but movement; not where you are or what you have, but where you have come from, where you are going and the rate at which you are getting there. -

The Morant Bay Rebellion in Jamaica

timeline The Morant Bay Rebellion in Jamaica Questions A visual exploration of the background to, and events of, this key rebellion by former • What were the causes of the Morant Bay Rebellion? slaves against a colonial authority • How was the rebellion suppressed? • Was it a riot or a rebellion? • What were the consequences of the Morant Bay Rebellion? Attack on the courthouse during the rebellion The initial attack Response from the Jamaican authorities Background to the rebellion Key figures On 11 October 1865, several hundred black people The response of the Jamaican authorities was swift and brutal. Making Like many Jamaicans, both Bogle and Gordon were deeply disappointed about Paul Bogle marched into the town of Morant Bay, the capital of use of the army, Jamaican forces and the Maroons (formerly a community developments since the end of slavery. Although free, Jamaicans were bitter about ■ Leader of the rebellion the mainly sugar-growing parish of St Thomas in the of runaway slaves who were now an irregular but effective army of the the continued political, social and economic domination of the whites. There were ■ A native Baptist preacher East, Jamaica. They pillaged the police station of its colony), the government forcefully put down the rebellion. In the process, also specific problems facing the people: the low wages on the plantations, the ■ Organised the secret meetings weapons and then confronted the volunteer militia nearly 500 people were killed and hundreds of others seriously wounded. lack of access to land for the freed people and the lack of justice in the courts. -

Global Encounters and the Archives Global Encounters a Nd the Archives

1 Global Encounters and the Archives Global EncountErs a nd thE archivEs Britain’s Empire in the Age of Horace Walpole (1717–1797) An exhibition at the Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University October 20, 2017, through March 2, 2018 Curated by Justin Brooks and Heather V. Vermeulen, with Steve Pincus and Cynthia Roman Foreword On this occasion of the 300th anniversary of Horace In association with this exhibition the library Walpole’s birthday in 2017 and the 100th anniversary will sponsor a two-day conference in New Haven of W.S. Lewis’s Yale class of 2018, Global Encounters on February 9–10, 2018, that will present new and the Archives: Britain’s Empire in the Age of Horace archival-based research on Britain’s global empire Walpole embraces the Lewis Walpole Library’s central in the long eighteenth century and consider how mission to foster eighteenth-century studies through current multi-disciplinary methodologies invite research in archives and special collections. Lewis’s creative research in special collections. bequest to Yale was informed by his belief that “the cynthia roman most important thing about collections is that they Curator of Prints, Drawings and Paintings furnish the means for each generation to make its The Lewis Walpole Library own appraisals.”1 The rich resources, including manuscripts, rare printed texts, and graphic images, 1 W.S. Lewis, Collector’s Progress, 1st ed. (New York: indeed provide opportunity for scholars across Alfred A. Knopf, 1951), 231. academic disciplines to explore anew the complexities and wide-reaching impact of Britain’s global interests in the long eighteenth century Global Encounters and the Archives is the product of a lively collaboration between the library and Yale faculty and graduate students across academic disci- plines. -

CSEC History Resource Guide

CSEC HISTORY RESOURCE GUIDE (REVISED 2016) Key primary and secondary resources for the study of CXC Caribbean History CSEC History Resource Guide This guide contains a select list of key primary and secondary resources (books, photographs, manuscripts, maps, newspapers) from the CSEC History Syllabus that are available at the National Library of Jamaica (NLJ). Also contained are additional resources, not listed in the syllabus, based on the 9 themes outlined in the syllabus. Some materials are available online but for some are only available in print format at the library. See more on using the library How to use this guide The guide is formatted similar to the CXC syllabus, with the author on the right, and title and publication information on the left and includes the library’s call/classification #. For example, Greenwood, R. A Sketch map History of the Caribbean. Oxford: Macmillan Education, 1991. 972.9 WI Gre Title & Publication Author call/classification # It is divided into three sections: Section 1: sources for general background reading Section 2: sources on the core section of the syllabus Sections 3: divided into the nine themes covered by the syllabus For each section, the primary sources are separated from the secondary sources With you topic in mind, go to the theme relevant to your topic. Look at the list of resources, read the notes, look at the date and type of source Click on link if online full text is available OR After identifying a resource that you want, make note of the title author and library call number. Complete a request slip at the library, give slip to library attendant. -

Sovereignty, War, and the Global State

Sovereignty, War, and the Global State Dylan Craig Sovereignty, War, and the Global State Dylan Craig Sovereignty, War, and the Global State Dylan Craig School of International Service American University Washington, DC, USA ISBN 978-3-030-19885-5 ISBN 978-3-030-19886-2 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-19886-2 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2020 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. The publisher remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. Cover illustration: © Alex Linch / shutterstock.com This Palgrave Macmillan imprint is published by the registered company Springer Nature Switzerland AG The registered company address is: Gewerbestrasse 11, 6330 Cham, Switzerland ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This book is the product of nine years of consistent focus on the conduct of violence by states using irregular forces in geopolitically complex condi- tions. -

SLAVE HOUNDS and ABOLITION in the AMERICAS* Downloaded from by Guest on 30 September 2021 I

SLAVE HOUNDS AND ABOLITION IN THE AMERICAS* Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/past/article/246/1/69/5722095 by guest on 30 September 2021 I INTRODUCTION In 1824 an anonymous Scotsman travelled through Jamaica to survey the island’s sugar plantations and social conditions. Notably, his journal describes an encounter with a formidable dog and its astonishing interaction with the enslaved. The traveller’s host, a Mr McJames, made ‘him a present of a fine bloodhound’ descended from a breed used for ‘hunting Maroons’ during Jamaica’s Second Maroon War almost three decades earlier.1 The maroons had surrendered to the British partly out of terror of these dogs, a Cuban breed that officials were promoting for use in Jamaica on account of their effectiveness in quelling black resistance.2 Unfamiliar with the breed, the traveller observed its ‘astounding ...aversion ...to the slaves’. For instance, when a young slave entered his room to wake him early one morning, the animal viciously charged the boy. The Scotsman judged that, without his intervention, the * We should like to thank Matt D. Childs and the Atlantic History Reading Group at the University of South Carolina for critiquing early stages of this article; Karl Appuhn, Joyce Chaplin, Deirdre Cooper Owens, Alec Dun and Dan Rood for commenting on conference papers; and our colleagues Erica Ball, Chris Ehrick and Tracy K’Meyer for sharing advice. Earlier versions of this project benefited from feedback at meetings of the American Society for Environmental History, King’s College London Animal History Group, the Washington Early American Seminar Series, the Society for Historians of the Early American Republic, the Forum on European Expansion and Global Interaction, the Omohundro Institute and the Society of Early Americanists. -

Reflections on Scotland, the Caribbean and the Atlantic World, C

Morris, Michael (2013) Atlantic Archipelagos: A Cultural History of Scotland, the Caribbean and the Atlantic World, c.1740-1833. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/3863/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Atlantic Archipelagos: A Cultural History of Scotland, the Caribbean and the Atlantic World, c.1740-1833. Michael Morris Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Department of English Literature School of Critical Studies University of Glasgow September 2012 2 Abstract This thesis, situated between literature, history and memory studies participates in the modern recovery of the long-obscured relations between Scotland and the Caribbean. I develop the suggestion that the Caribbean represents a forgotten lieu de mémoire where Scotland might fruitfully ‘displace’ itself. Thus it examines texts from the Enlightenment to Romantic eras in their historical context and draws out their implications for modern national, multicultural, postcolonial concerns. Theoretically it employs a ‘transnational’ Atlantic Studies perspective that intersects with issues around creolisation, memory studies, and British ‘Four Nations’ history. -

Alex Adams Phi Alpha Theta Paper

The white inhabitants wished relief from the horrors of continual alarms...: The British Empire, Planter Politics, and the Agency of Jamaican Slaves and Maroons Item Type Presentation Authors Adams, Alex Download date 23/09/2021 15:40:44 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12648/1178 !1 “The white inhabitants wished relief from the horrors of continual alarms…”1 The British Empire, Planter Politics, and the Agency of Jamaican Slaves and Maroons Alex Adams Castleton University Phi Alpha Theta Conference, April 30, 2016 Although agency is generally depicted as local actions triggering local results, fears caused by the agency of slaves and Maroons in Jamaica influenced the policies of the British Empire by affecting the agendas of worried planter politicians who had one foot in Jamaica and the other in Britain.2 Kathleen Wilson argues that “examining [Maroon’s] roles within the larger theaters of British colonial power … can illuminate their contribution to the Jamaican colonial order.”3 This paper suggests that Maroons’ influence extended to the heart of British imperial politics, the British Parliament. It joins a conversation among historians associated with the “New Imperial History” which has reversed the trend of exploring the British Empire in terms of how the metropole influenced the world, instead focusing on how the world impacted the British Empire. For example, Antoinette Burton, a leader in this field of British imperial history, ex- plores the influence of distant British subjects on their metropolitan center in The Trouble With 1 Edward Long, The History of Jamaica. or General Survey of the Antient and Modern State of that Island: with Reflections of its Situation, Settlements, Inhabitants, Climate, Products, Commerce, Laws, and Government II (Lon- don: Printed for T. -

Engaging Origins, Tradition and Sovereignty Claims of Jamaican Maroon Communities

The Work of Diaspora: Engaging Origins, Tradition and Sovereignty Claims of Jamaican Maroon Communities By Mario Nisbett A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in African American Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Percy C. Hintzen, Chair Professor Na’ilah Suad Nasir Professor Laurie A. Wilkie Summer 2015 © 2015 by Mario Nisbett All Rights Reserved Abstract The Work of Diaspora: Engaging Origins, Tradition and Sovereignty Claims of Jamaican Maroon Communities by Mario Nisbett Doctor of Philosophy in African American Studies University of California, Berkeley Professor Percy C. Hintzen, Chair This dissertation examines the concept of the African Diaspora by focusing on four post-colonial Maroon communities of Jamaica, the oldest autonomous Black polities in the Caribbean, which were established by escapees from slave-holding authorities during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. In exploring the Maroons as a Black community, the work looks at how they employ diaspora in making linkages to other communities of African descent and for what purposes. Maroons are being positioned in relation to the amorphous concept of diaspora, which is normally used to refer to people who have been dispersed from their place of origins but maintain tradition and connections with kin in other countries. However, I complicate the definition, arguing that diaspora, specifically the African Diaspora, is the condition that produces the collective consciousness of sameness rooted in the idea of common African origins based on a common experience of Black abjection. This understanding of diaspora opens the way to see that the uses of the concept are varied. -

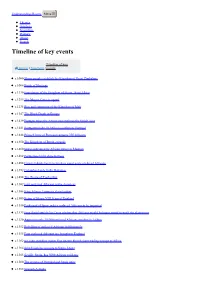

Timeline of Key Events. Understanding Slavery Initiative

Understanding Slavery Menu Themes Artefacts Secondary Primary About Search Timeline of key events Timeline of key Home / Teachers / events c.1000 Shona people establish the Kingdom of Great Zimbabwe c.1066 Battle of Hastings c.1130 Foundation of the Kingdom of Benin, West Africa c.1215 The Magna Carta is signed c.1235 Rise and expansion of the Kingdom of Mali c.1347 The Black Death in Europe c.1439 Portugal takes the Azores and explores the Gold Coast c.1441 Portuguese take 10 African captives to Portugal c.1444 Prince Henry of Portugal captures 235 Africans c.1450 The Kingdom of Benin expands c.1460 Sugar cultivated by African slaves in Madeira c.1482 Portuguese build slave fortress c.1484 Canary Islands begin to produce sugar using enslaved Africans c.1492 Columbus lands in the Bahamas c.1494 The Treaty of Tordesillas c.1502 First enslaved Africans in the Americas c.1506 King Afonso I opposes slave traders c.1509 Reign of Henry VIII, King of England c.1510 Ferdinand of Spain orders enslaved Africans to be imported c.1535 Frey Bartolomé de las Casas advises that Africans would be better suited to work the plantations c.1550 Approximately 10,000 enslaved Africans resident in Lisbon c.1552 Rebellion of enslaved Africans in Hispaniola c.1555 First enslaved Africans are brought to England c.1562 Sir John Hawkins makes first known British slave trading voyage to Africa c.1564 John Hawkins voyages to Sierra Leone c.1565 Seville, Spain, has 5000 African residents c.1580 The crowns of Portugal and Spain unite c.1588 Spanish Armada c.1591 Fall of the Songhay Kingdom c.1592 Dutch end Portuguese monopoly c.1600 Dutch enter the trade c.1601 Elizabeth I expels African people c.1607 Colony of Virginia is founded c.1610 Up to 135,000 English go to the Caribbean c.1618 British Crown allows the Guinea Company to trade with West Africa c.1619 Beginning of the trade in enslaved Africans in Virginia c.1620 Pilgrim Fathers set sail for America c.1621 Dutch West India Co. -

Caribbean: the Jamaican Maroons and Creek Nation Compared

Negotiating Freedom in the Circum- Caribbean: The Jamaican Maroons and Creek Nation Compared Helen Mary McKee A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy School of History, Classics and Archaeology May 2015 Abstract Built on an investigation of a large number of archival sources in three different countries, this study analyses free, non-white communities in the circum-Caribbean. Using the comparative method, I assess how the Maroons and Creeks negotiated a role for themselves in an inter-war context, exploring their interactions with four main groups. First, I consider the Maroon and Creek relationship with the enslaved population of Jamaica and the United States, respectively. This allows me to demonstrate that the signing of the peace treaties with white society had little impact on interactions with slaves. Maroon and Creek attitudes towards slaves continued in much the same manner as before peace, it was the contexts in which these interactions that took place which changed. Second, I scrutinise how the two communities navigated the potentially inflammatory situation of peace with their former white enemies. I argue that the Maroons enjoyed a more amicable relationship than the Creeks did with the local white settlers. This was largely a result of the fact that the Maroons and local whites shared a mutual usefulness whereas the Creeks and local whites did not. Third, I compare the Maroon alliance with the colonial government of Jamaica with that of the Creek and federal government. I show that, initially, both governments appreciated the usefulness of such an allegiance but, as time passed and the Maroons and Creeks showed no indication of submissiveness, both soon moved to restrict, and ultimately reduce, the independence of the societies.