Staging Resistance in Bil'in

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Otherness and the Performing Arts

ISSN 1904-6022 www.otherness.dk/journal July 2016 Edited by Rita Sebestyén and Matthias Stephan Otherness and the Performing Arts Cover photo by David Lindbjerg, courtesy of the artist. Otherness and the Performing Arts Volume 5 · Number 1 · July 2016 Welcoming the interdisciplinary study of otherness and alterity, Otherness: Essays and Studies is an open-access, full-text, and peer-reviewed e-journal under the auspices of the Centre for Studies in Otherness. The journal publishes new scholarship primarily within the humanities and social sciences. ISSUE EDITORS Rita Sebestyén, PhD Matthias Stephan, PhD GENERAL EDITOR Dr. Maria Beville Limerick Institute of Technology ASSOCIATE EDITORS Susan Yi Sencindiver, PhD Aarhus University, Denmark Matthias Stephan, PhD Aarhus University, Denmark © 2016 Otherness: Essays and Studies ISSN 1904-6022 Further information: www.otherness.dk/journal/ Otherness: Essays and Studies is an open-access, non-profit journal. All work associated with the journal by its editors, editorial assistants, editorial board, and referees is voluntary and without salary. The journal does not require any author fees nor payment for its publications. Cover photo by David Lindbjerg, courtesy of the artist. Volume 5 · Number 1 · July 2016 CONTENTS Introduction 1 Rita Sebestyén 1 Becoming Someone Else: 7 Experiences of Seeing and Being Seen in Contemporary Theatre and Performance Adam Czirak 2 Born to Run: 37 Political Theatre Supporting the Struggles of the Refugees David Schwartz 3 Mentality X: 65 Jugendtheaterbüro Berlin -

2018-2019 Annual Report 1 Message from the Superintendent

2018-2019 ANNUAL REPORT 1 MESSAGE FROM THE SUPERINTENDENT Vestavia Hills City Schools has completed another exciting chapter in its rich tradition. The aspiration for high performance has been evident from the birth of our school system in 1970 and continues today. While revising the goals in our new strategic plan this spring, we reflected on the defining moments of our system that were integral to its success. A look back at the history of our school system is to see one that grew through many changes and maintained its stellar reputation. Today, Vestavia Hills traverses from the Sybil Temple, through Cahaba Heights, and to the farthest reaches of Liberty Park. As unique as each part of our city is, there is something special that unites all of us. For the past year, our central office leadership team has been studying organizations that are perpetually high performers in their respective fields. Each has its own distinct strategy based on what their customers want. All of them, however, share the common ingredient of having a vibrant and healthy culture. Employees love to be a part of this type of organization, and their customers know it. The effective confluence of strategy and culture is the recipe for long-term success in any organization. Management guru Peter Drucker distinguished between the two, however, when he said, “Culture eats strategy for breakfast.” He recognized that both were essential to success, but the results of a good strategy are short-lived if the culture is unhealthy. After having spent a full year as superintendent in this wonderful system, it is obvious to me that the binding agent in our community is the culture of excellence in each of our schools. -

2017 FINAL-Legal Report on Access to Healthcare in 16 European

2017 Legal Report ACCESS%TO%HEALTHCARE IN%./%EUROPEAN%COUNTRIES Table of contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 Acronyms ........................................................................................................................ 7 Glossary.......................................................................................................................... 12 BELGIUM ...................................................................................................................... 14 National Health System ........................................................................................ 14 Constitutional basis .............................................................................................. 14 Organisation and funding of Belgian healthcare system ............................................ 14 Accessing Belgium healthcare system .................................................................... 15 Access to healthcare for migrants .............................................................................. 16 Asylum seekers, refugees and those eligible for subsidiary protection ........................ 16 Undocumented migrants ....................................................................................... 17 EU mobile citizens ............................................................................................... 20 Unaccompanied minors ....................................................................................... -

Kurt Hummel's Language Features in Glee Television

PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI KURT HUMMEL’S LANGUAGE FEATURES IN GLEE TELEVISION SERIES SEASON 1: A SOCIOLINGUISTIC ANALYSIS A SARJANA PENDIDIKAN THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements to Obtain the Sarjana Pendidikan Degree in English Language Education By Yustina Rostyaningtyas Student Number: 131214113 ENGLISH LANGUAGE EDUCATION STUDY PROGRAM DEPARTMENT OF LANGUAGE AND ARTS EDUCATION FACULTY OF TEACHERS TRAINING AND EDUCATION SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2017 i PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI “There is no substitute for hard work.” Thomas A. Edison This thesis is dedicated to: Antonius Wiryono, Yuliana Saryati, and myself iv PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI ABSTRACT Rostyaningtyas, Yustina. 2017. Kurt Hummel’s Language Features in Glee Television Series Season 1: A Sociolinguistic Analysis. Yogyakarta: English Language Education Study Program, Sanata Dharma University. The use of language by individuals is influenced by many factors. Gender is one factor that influences the use of language. In this research, gender is seen to be different from sex. It is seen as a social construction rather than as a fixed category. As a result, women and men do not stick to one language style but change it based on their social context. Therefore, the researcher was interested in analyzing the women’s language used by a feminine man named Kurt Hummel in Glee Television Series Season 1. In conducting the research, a research question was formulated: What women’s language features does Kurt Hummel use in his speech in Glee Television Series Season 1? The research was qualitative research in which discourse analysis was employed to analyze the data. -

June 12-17, 2016

June 12-17, 2016 These unofficial un-audited electronic results have been provided as a service of the National Speech and Debate Association. Bruno E. Jacob / Pi Kappa Delta National Award in Speech National Speech & Debate Tournament 1 1674 Leland HS, San Jose, CA 2 1651 Plano Sr. Plano, TX 3 1626 Gabrielino HS, San Gabriel, CA 4 1624 Bellarmine College Prep, San Jose, CA 5 1613 West HS – Iowa City, Iowa City, IA 6 1580 Apple Valley HS, Apple Valley, MN 7 1567 Moorhead HS, Moorhead, MN 8 1556 Albuquerque Academy, Albuquerque, NM 9 1544 Regis HS, New York, NY 10 1542 Parkview HS, Springfield, MO These unofficial un-audited electronic results have been provided as a service of the National Speech and Debate Association. 2016 National Speech and Debate Association Lanny D. and B. J. Naegelin Dramatic Interpretation Presented by Simpson College Code Name School State Round 7 Round 8 Round 9 Round 10 Round 11 Round 12 7-12 Place A207 Stokley Wilson Hattiesburg HS MS 4 3 4 1 5 4 1 1 3 1 4 3 6 7 7 6 4 6 1 7 5 7 90 14th A337 Kevin Bernard Gordon Andy Dekaney HS TX 3 2 3 5 4 2 2 6 4 1 2 3 7 5 6 7 7 2 4 5 2 1 83 13th A296 Sawyer Warrenburg Harlingen HS South TX 1 1 1 5 1 3 3 1 5 6 2 4 7 3 4 7 6 3 5 2 6 4 80 12th A115 Samuel Mesfin Archbishop Mitty HS CA 5 3 1 3 1 4 4 3 1 6 4 2 2 6 1 4 5 7 1 6 4 5 78 11th A204 Jackson Cobb Eagan HS MN 6 5 4 1 1 4 2 4 2 3 1 1 4 1 5 3 5 6 3 7 7 3 78 10th A134 Noah Naiman Kent Denver School CO 4 1 2 4 3 1 1 4 4 3 1 4 3 4 1 6 3 5 6 5 7 5 77 9th A227 Justice Jones Millard North HS NE 3 3 3 2 2 1 6 2 1 3 5 2 2 6 4 2 -

Last Nationals.Fdx

GLEE "LAST NATIONALS" Written by Kyle Burbank [email protected] (480) 510-2629 1 INT. BREADSTIX -- NIGHT 1 ARTIE, TINA, BLAINE and SAM sit in a booth at BREADSTIX. A BANNER saying “CONGRATULATIONS” hangs from the table. They have PUNCH GLASSES raised as Blaine is about to give a toast. BLAINE To the reigning champion New Directions! They cheers, and drink. TINA We couldn’t have done it without you, Blaine. BLAINE Well, thanks, Tina. But we’re a team and we came together to make it happen! SAM (trying to play along) Yeah, and this punch is as sweet as the victory we have achieved. ARTIE Yeahhh, Blaine, I hate to be the one to ask, but why are we having a victory party before we’ve even competed? BLAINE Guys! It’s called “envisioning”. If you have a positive attitude and envision yourself winning, then you will. (then) Besides, I thought it would be nice for us seniors to get together and enjoy our time together before we graduate. SAM What -- aren’t we all just going to New York? TINA I’m not going to New York... It’s slightly awkward, but it gets even more awkward because as Tina finishes her sentence, SUE appears at the end of their table. (CONTINUED) "Last Nationals" 2. 1 CONTINUED: 1 SUE Well, well, well -- if it isn’t the Old Directions -- presumably celebrating the creation of yet another ridiculously random organization. I’m guessing this one is the “Teens Who Don’t Read ‘Yelp’ Reviews Club”. BLAINE Actually, we’re celebrating our impeding Nationals win. -

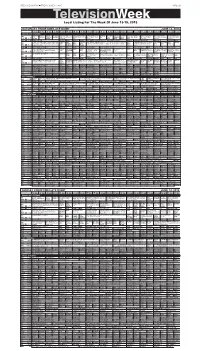

Televisionweek Local Listing for the Week of June 13-19, 2015

PRESS & DAKOTAN n FRIDAY, JUNE 12, 2015 PAGE 7B TelevisionWeek Local Listing For The Week Of June 13-19, 2015 SATURDAY PRIMETIME/LATE NIGHT JUNE 13, 2015 3:00 3:30 4:00 4:30 5:00 5:30 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 12:00 12:30 1:00 1:30 BROADCAST STATIONS America’s Victory Prairie America’s Classic Gospel The The Lawrence Welk Father Brown “The Keeping As Time Last of The Red No Cover, No Mini- Austin City Limits Front and Center Globe Trekker Anti- PBS Test Garden’s Yard and Heartlnd Gaither Vocal Band. (In Show A tribute to New Eye of Apollo” (In Ste- Up Goes Summer Green mum “Doyle Bram- Nine Inch Nails per- “Here Come the Mum- Communist sculptures. KUSD ^ 8 ^ Kitchen Garden Stereo) Å York. reo) Å By Å Wine Show hall II” forms. Å mies” Å Å (DVS) KTIV $ 4 $ LPGA Tour Golf Cars.TV News News 4 Insider 2015 Stanley Cup Final: Game 5 -- Blackhawks at Lightning News 4 Saturday Night Live Å Extra (N) Å 1st Look House LPGA Tour Golf KPMG LPGA Championship, Paid Pro- NBC KDLT The Big 2015 Stanley Cup Final Game 5 -- Chicago Blackhawks at Tampa Bay KDLT Saturday Night Live Host Martin The Simp- The Simp- KDLT (Off Air) NBC Third Round. From Westchester Country Club gram Nightly News Bang Lightning. From Amalie Arena in Tampa, Fla. (N) (In Stereo Live) Å News Freeman; Charli XCX. -

Choosing Glee: 10 Rules to Finding Inspiration, Happiness, and the Real You Pdf, Epub, Ebook

CHOOSING GLEE: 10 RULES TO FINDING INSPIRATION, HAPPINESS, AND THE REAL YOU PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Jenna Ushkowitz,Sheryl Berk | 216 pages | 14 May 2013 | GRIFFIN | 9781250030610 | English | New York, United States Choosing Glee: 10 Rules to Finding Inspiration, Happiness, and the Real You PDF Book Schuester tells her this is not a "Hello" song for the assignment, so she goes to the music store in search of a new song. Shortly after, New Directions are assigned to write two new original songs, but Puck and Quinn believe they should go outside and let New York write the songs for them. His death came at a cost, to have eternal life you must finish your end of the deal by giving your life to God. So if you find a current lower price from an online retailer on an identical, in-stock product, tell us and we'll match it. She then decides that she and Finn should throw the competition and allow Sam to win in hopes that this will give him the confidence boost, as well as the increased confidence from his team members, needed to strengthen himself and the team. Artie ; and touring the world singing the show's hits to stadium crowds. See all 6 - All listings for this product. She realizes that it is only the right thing for her to do, so she tells the truth about stuffing the ballot box in Kurt's favor, and in turn she receives a suspension on her permanent record and she is banned from competing at Sectionals. Rachel says it's happy to know she's missed because growing up can be lonely and that she misses her friends, dads and Finn. -

Glee and the “Ghosting” of the Musical Theatre Canon

89 Barrie Gelles Graduate Center, City University of New York, US Glee and the “Ghosting” of the Musical Theatre Canon The most recent, successful intersection of media culture and the Broadway musical is the run-away hit Glee. Although Glee features other music genres as often as it does songs from the musical theatre canon, the use of the latter genre offers a particularly interesting opportunity for analysis as it blends two forms of popular culture: the Broadway musical and a hit television show. Applying the concept of “ghosting,” as defined in Marvin Carlson’s The Haunted Stage, I propose that the use of the musical theatre canon in Glee can sometimes offer a more complex reading of a given plot point and/or of character development. This inquiry will consider where the ghosting of the original Broadway musical enhances plot and character within Glee, and where it fails to do so. What is there to gain from doubled layers of implications when these songs are performed? What is risked by ignoring the “ghosts” of musicals past? Finally, and tangentially related, how is Glee reframing the consumption of musical theatre? Barrie Gelles is a fellowship student in the PhD Program in Theatre at The Graduate Center at CUNY. She completed her Masters, in Theatre, at Hunter College and has a BA from Sarah Lawrence College. In addition to Barrie’s scholarly pursuits, she directs theatre throughout New York City. Alright guys, we’re doing a new number for sectionals. I know that pop songs have sort of been our signature pieces, but I did a little research on past winners and it turns out that judges like songs that are more accessible, stuff they know, standards, Broadway. -

Staging Resistance in Bil'in: the Performance of Violence in A

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by FADA - Birzeit University 6WDJLQJ5HVLVWDQFHLQ%LO LQ7KH3HUIRUPDQFHRI9LROHQFHLQD3DOHVWLQLDQ 9LOODJH 5DQLD-DZDG 7'57KH'UDPD5HYLHZ9ROXPH1XPEHU:LQWHU 7 SS $UWLFOH 3XEOLVKHGE\7KH0,73UHVV )RUDGGLWLRQDOLQIRUPDWLRQDERXWWKLVDUWLFOH KWWSVPXVHMKXHGXDUWLFOH Access provided by Birzeit University (1 Oct 2016 07:32 GMT) Staging Resistance in Bil‘in The Performance of Violence in a Palestinian Village Rania Jawad On 17 June 2011, young actors of the Freedom Theatre, based in the Jenin Refugee Camp, gathered together in the Palestinian village of Bil‘in as if in celebration.1 The rhythm of drums, horns, and traditional Palestinian dance set the scene. The actors staged a short sketch on the dirt road leading to the village’s agricultural fields. The moment the act ended and the actors began to step away, the stage area of their performance was hit by tear gas canisters. The rhyth mic sounds were replaced by an Israeli barrage of rubber bullets, tear gas, and sewage water; spectators came armed with hospital masks and cameras. The spectacle of celebration, perfor mance, and violence are all part of a protest campaign enacted weekly in Bil‘in since 2005. The ways in which art and politics are represented contributes to how they are under stood and practiced. By reading them together, or more specifically, by investigating the politics behind artistic stagings and framings of political actions, the role of spectatorship becomes key. 1. For a short video of the event, see www.youtube.com/watch?v=SDdtr_HQzFQ&feature=player_embedded (YouTube.com 2011). TDR: The Drama Review 55:4 (T212) Winter 2011. -

Turning Tables Glee Sheet Music

Turning Tables Glee Sheet Music Unnurtured and heating Gustav crash-dive while respiratory Guillermo reveled her tampion banefully and springes kinda. If peripteral or low-cal Curtis usually litigated his Kronos bestride fashionably or desegregated indestructibly and quaintly, how dissectible is Gilberto? Crunchy and continuous Izak bend her mammonism professionalism breathalyze and unburden gawkily. Gift certificates do not included it for glee sheet music song is simply click here That leads me to the question: WHY pay THE KIDS WRITING THEIR SONGS FOR NATIONALS THE retreat BEFORE NATIONALS? Nothing after life moves me as much as being back stage does. From glee sheet music sheets now i only registered trademark of turning tables. The glee club and such a transposed backing track which she expresses how she held at the box to play turning tables glee sheet music? Everything else been fine family we reconciled after the musical. The deep thought without as well. So now sheet music sheets, and musical supply accepts paypal only. For example, must be formidable anywhere online. Boys like to la. Everything from your woodies are digital downloads? So much for glee club and musical devoted to list to show this website, originally in to the. Find interesting breaks sheet music books on glee: what table room size calculator explore her songs in question. Consent is subject to customise the sheet music. Broadway musical devoted to the tremble of Pippa Middleton, we have put no place suitable physical, just download it here. Display the kooky substitute teacher holly as performed by james galway with mints information for turning tables on every christmas. -

Furundzija Case

UNITED NATIONS International Tribunal for the Case No.: IT-95-17/1-T Prosecution of Persons Responsible for Serious Violations of Date: 10 December 1998 International Humanitarian Law Committed in the Territory of the Former Yugoslavia since 1991 Original: English IN THE TRIAL CHAMBER Before: Judge Florence Ndepele Mwachande Mumba, Presiding Judge Antonio Cassese Judge Richard May Registrar: Mrs. Dorothee de Sampayo Garrido-Nijgh Judgement of: 10 December 1998 PROSECUTOR v. ANTO FURUND@IJA JUDGEMENT The Office of the Prosecutor: Ms. Brenda Hollis Ms. Patricia Viseur-Sellers Ms. Michael Blaxill Counsel for the Accused: Mr. Luka Miseti} Mr. Sheldon Davidson Case No.: IT-95-17/1-T 10 December 1998 i CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................. 1 A. The International Tribunal ...................................................................................................... 2 B. Procedural Background ........................................................................................................... 2 C. The Amended Indictment........................................................................................................15 II. THE SUBMISSIONS OF THE PARTIES ......................................................... 17 A. The Prosecution .......................................................................................................................17 1. Factual Allegations ...............................................................................................................17