An Overview of China's Recent Domestic and International Air

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pilot Movers Westair

PILOTMOVERS IS DELIGHTED TO BE RECRUITING FOR A320 CAPTAINS ON BEHALF OF WEST AIR WEST AIR West Air is member of Hainan Group of airlines, the largest non-Stated owned airline group in China. It operates a scheduled passenger network to 18 domestic destinations out of Chongqing Jiangbei International Airport. The company was established in March 2006 by its parent company Hainan Airlines with the launch of scheduled services on 14 July 2010. There has been a consistent increase in West Air fleet size of A320 family aircraft since starting operations. They currently operate 27 x A320 series aircraft and plan to have a severe fleet expansion in the coming years. West Air is member of Hainan Group of airlines, the largest non-Stated owned airline group in China. PILOTMOVERS IN CHINA PilotMovers was set up by pilots with over 25 years experience in the industry. We have inside expertise and we are currently flying in China, that is why we can offer on site and on-line support. PilotMovers is the only agency that has his own in-house specialist for Insurance and loss of licence solutions. We have very attractive deals on these packages as we adhere to group discount rates Our pilots receive personalised attention, customised FLY4FREEDOM preparation packages and unique know-how of several Chinese airlines. We know what pilots expect and pilot to pilot communication is one of our main assets. We can provide you with significant increase of your success probabilities in order to achieve your goal: Get one of the top paid pilot jobs in the world. -

IATA CLEARING HOUSE PAGE 1 of 21 2021-09-08 14:22 EST Member List Report

IATA CLEARING HOUSE PAGE 1 OF 21 2021-09-08 14:22 EST Member List Report AGREEMENT : Standard PERIOD: P01 September 2021 MEMBER CODE MEMBER NAME ZONE STATUS CATEGORY XB-B72 "INTERAVIA" LIMITED LIABILITY COMPANY B Live Associate Member FV-195 "ROSSIYA AIRLINES" JSC D Live IATA Airline 2I-681 21 AIR LLC C Live ACH XD-A39 617436 BC LTD DBA FREIGHTLINK EXPRESS C Live ACH 4O-837 ABC AEROLINEAS S.A. DE C.V. B Suspended Non-IATA Airline M3-549 ABSA - AEROLINHAS BRASILEIRAS S.A. C Live ACH XB-B11 ACCELYA AMERICA B Live Associate Member XB-B81 ACCELYA FRANCE S.A.S D Live Associate Member XB-B05 ACCELYA MIDDLE EAST FZE B Live Associate Member XB-B40 ACCELYA SOLUTIONS AMERICAS INC B Live Associate Member XB-B52 ACCELYA SOLUTIONS INDIA LTD. D Live Associate Member XB-B28 ACCELYA SOLUTIONS UK LIMITED A Live Associate Member XB-B70 ACCELYA UK LIMITED A Live Associate Member XB-B86 ACCELYA WORLD, S.L.U D Live Associate Member 9B-450 ACCESRAIL AND PARTNER RAILWAYS D Live Associate Member XB-280 ACCOUNTING CENTRE OF CHINA AVIATION B Live Associate Member XB-M30 ACNA D Live Associate Member XB-B31 ADB SAFEGATE AIRPORT SYSTEMS UK LTD. A Live Associate Member JP-165 ADRIA AIRWAYS D.O.O. D Suspended Non-IATA Airline A3-390 AEGEAN AIRLINES S.A. D Live IATA Airline KH-687 AEKO KULA LLC C Live ACH EI-053 AER LINGUS LIMITED B Live IATA Airline XB-B74 AERCAP HOLDINGS NV B Live Associate Member 7T-144 AERO EXPRESS DEL ECUADOR - TRANS AM B Live Non-IATA Airline XB-B13 AERO INDUSTRIAL SALES COMPANY B Live Associate Member P5-845 AERO REPUBLICA S.A. -

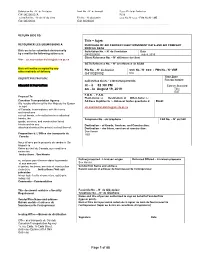

G410020002/A N/A Client Ref

Solicitation No. - N° de l'invitation Amd. No. - N° de la modif. Buyer ID - Id de l'acheteur G410020002/A N/A Client Ref. No. - N° de réf. du client File No. - N° du dossier CCC No./N° CCC - FMS No./N° VME G410020002 G410020002 RETURN BIDS TO: Title – Sujet: RETOURNER LES SOUMISSIONS À: PURCHASE OF AIR CARRIER FLIGHT MOVEMENT DATA AND AIR COMPANY PROFILE DATA Bids are to be submitted electronically Solicitation No. – N° de l’invitation Date by e-mail to the following addresses: G410020002 July 8, 2019 Client Reference No. – N° référence du client Attn : [email protected] GETS Reference No. – N° de reference de SEAG Bids will not be accepted by any File No. – N° de dossier CCC No. / N° CCC - FMS No. / N° VME other methods of delivery. G410020002 N/A Time Zone REQUEST FOR PROPOSAL Sollicitation Closes – L’invitation prend fin Fuseau horaire DEMANDE DE PROPOSITION at – à 02 :00 PM Eastern Standard on – le August 19, 2019 Time EST F.O.B. - F.A.B. Proposal To: Plant-Usine: Destination: Other-Autre: Canadian Transportation Agency Address Inquiries to : - Adresser toutes questions à: Email: We hereby offer to sell to Her Majesty the Queen in right [email protected] of Canada, in accordance with the terms and conditions set out herein, referred to herein or attached hereto, the Telephone No. –de téléphone : FAX No. – N° de FAX goods, services, and construction listed herein and on any Destination – of Goods, Services, and Construction: attached sheets at the price(s) set out thereof. -

A Famous Chinese Brand and Fleets

ASCEND I PROFILE y most accounts, the first double-digit passenger traffic growth from decade of the 21st century 2004 through 2010, according to the Civil presented unprecedented chal- Aviation Administration of China (CAAC). While lenges for the global airline that growth has slowed during the last two industry worldwide. In fact, years, it is still the highest in the world. Total manyB industry analysts have labeled the first profits for China’s airline industry in 2011 alone 10 years of this century as the “lost decade,” are an estimated US$7.2 billion, accounting citing: for more than half the profits of the entire Massive layoffs, worldwide airline industry. Staggering financial losses, Leading the way are China’s “big three” Record numbers of bankruptcies and con- carriers — Air China, China Southern Airlines solidations, and China Eastern Airlines, followed by a Skyrocketing fuel prices, strengthening number of second-tier carriers. Declining consumer confidence, While expansion has been a major focus Widespread service disruptions attributed to of China’s aviation industry during the first pandemics, volcanic ash and wild weather decade, flexibility — the ability to adapt quickly patterns. to the volatile marketplace — continues to be Along with the challenges, the decade also a priority. brought myriad opportunities for the industry. China Eastern was the first Chinese civil The tragic events of Sept. 11, 2001, in the aviation company to be listed simultaneously United States, it appears, were the first of on the Hong Kong, New York and Shanghai many catalysts that drove airlines worldwide stock exchanges. It has carefully and success- to evaluate and fundamentally restructure the fully navigated the industry’s last few turbulent way they do business. -

There Are 2 Direct Flights Between Lhasa and Kathmandu, Run by Sichuan Airline and Air China Separately, While the Sichuan Airline Departs Every Other Day

Flights from Kathmandu to Lhasa and Lhasa to Kathmandu Until today (May 2, 2016), there are 2 direct flights between Lhasa and Kathmandu, run by Sichuan Airline and Air China separately, while the Sichuan Airline departs every other day. Besides, there are also a few connecting flights between Lhasa and Kathmandu, stopover in Chongqing, Kunming and Chengdu. Air China: Lhasa and Kathmandu Flight Schedule Flight Route Flight Code Airlines Dep. Arr. Type Schedule Air Lhasa to Kathmandu CA407 12:10 11:10 319 every day China Air Kathmandu to Lhasa CA408 12:10 16:00 319 every day China Sichuan Airline: Lhasa and Kathmandu Flight Shcedule Flight Route Flight Code Airlines Dep. Arr. Type Schedule Lhasa to Kathmandu 3U8719 Sichuan Airline 11:15 10:10 319 every other day Kathmandu to Lhasa 3U8720 Sichuan Airline 11:10 14:50 319 every other day Flights from Shanghai to Lhasa and Lhasa to Shanghai Currently, there are three direct flights which go via Chengdu or Xi'an between Lhasa and Shanghai, operated by China Eastern Airline, Tibet Airline and Air China. It takes about 7 hours for the flight in which about 1 hour is for stopover. In addition, a few of connecting flights stop at Chengdu, Chongqing and Kunming airport, then you can transfer flights to Lhasa. Air China: Lhasa and Shanghai Flight Schedule Flight Route Flight Code Airlines Dep. Arr. Type Stopover Schedule Air Lhasa to Shanghai CA3981 07:40 13:30 319 Chengdu every day China Air Shanghai to Lhasa CA3982 14:45 21:45 319 Chengdu every day China China Eastern Airline: Lhasa and Shanghai Flight Schedule Flight Route Flight Code Airlines Dep. -

China Eastern Airlines Corporation Limited ANNUAL REPORT 2018 M O C Ceair

China Eastern Airlines Corporation Limited www . ceair. c o m AN N UAL REPORT 2 01 8 Stock Code : A Share : 600115 H Share : 00670 ADR : CEA A joint stock limited company incorporated in the People's Republic of China with limited liability Contents 2 Defi nitions 98 Report of the Supervisory Committee 5 Company Introduction 100 Social Responsibilities 6 Company Profi le 105 Financial Statements prepared in 8 Financial Highlights (Prepared in accordance with International accordance with International Financial Reporting Standards Financial Reporting Standards) • Independent Auditor’s Report 9 Summary of Accounting and Business • Consolidated Statement of Profi t Data (Prepared in accordance with or Loss and Other PRC Accounting Standards) Comprehensive Income 10 Summary of Major Operating Data • Consolidated Statement of Financial 13 Fleet Structure Position 16 Milestones 2018 • Consolidated Statement of Changes 20 Chairman’s Statement in Equity 30 Review of Operations and • Consolidated Statement of Cash Management’s Discussion and Flows Analysis • Notes to the Financial Statements 53 Report of the Directors 232 Supplementary Financial Information 79 Corporate Governance Defi nitions In this report, unless the context otherwise requires, the following expressions have the following meanings: AFK means Air France-KLM, a connected person of the Company under the Shanghai Listing Rules Articles means the articles of association of the Company Available freight tonne-kilometres means the sum of the maximum tonnes of capacity available for the -

I Will Take You Through an Update on the Progress We Have Made Over the Past 2 Years and Also Provide Some Insight Into What You Should Expect for 2015

I will take you through an update on the progress we have made over the past 2 years and also provide some insight into what you should expect for 2015. We will begin with a short video which describes what the air travel shopping experience could look like with an NDC standard in place. This is not about IATA building a system for a travel agent! This is about illustrating how a travel IT provider could use the NDC standard to create exciting and comprehensive shopping interfaces for a travel agent or online travel site. The video shows how the NDC standard can help Online Travel Agents, Business Travel Agents and also Corporate travel departments (corporate booking tools). These mock ups were designed in consultation with focus groups of travel agents and corporate buyers over the last 18 months. 1 Reminder: This is not about IATA building a system. This is about illustrating how a travel IT provider could use the NDC standard to create exciting and comprehensive shopping interfaces for a travel agent or online travel site. 2 NDC is in effect the modernization of 40-year-old data exchange standards for ticket distribution developed before the Internet was invented. IATA was created nearly 70 years ago to set industry standards that facilitate safe and efficient air travel (e.g. e-ticketing, bar coded boarding passes, common use airport kiosks, etc. In the case of NDC, once again, IATA’s role will be to deliver the standards that enable such capabilities for our industry partners so as to be able to offer the passenger the opportunity to have a consistent shopping experience, wherever they shop for travel. -

The Impacts of Globalisation on International Air Transport Activity

Global Forum on Transport and Environment in a Globalising World 10-12 November 2008, Guadalajara, Mexico The Impacts of Globalisation on International Air Transport A ctivity Past trends and future perspectives Ken Button, School of George Mason University, USA NOTE FROM THE SECRETARIAT This paper was prepared by Prof. Ken Button of School of George Mason University, USA, as a contribution to the OECD/ITF Global Forum on Transport and Environment in a Globalising World that will be held 10-12 November 2008 in Guadalajara, Mexico. The paper discusses the impacts of increased globalisation on international air traffic activity – past trends and future perspectives. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS NOTE FROM THE SECRETARIAT ............................................................................................................. 2 THE IMPACT OF GLOBALIZATION ON INTERNATIONAL AIR TRANSPORT ACTIVITY - PAST TRENDS AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVE .................................................................................................... 5 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 5 2. Globalization and internationalization .................................................................................................. 5 3. The Basic Features of International Air Transportation ....................................................................... 6 3.1 Historical perspective ................................................................................................................. -

World Air Transport Statistics, Media Kit Edition 2021

Since 1949 + WATSWorld Air Transport Statistics 2021 NOTICE DISCLAIMER. The information contained in this publication is subject to constant review in the light of changing government requirements and regulations. No subscriber or other reader should act on the basis of any such information without referring to applicable laws and regulations and/ or without taking appropriate professional advice. Although every effort has been made to ensure accuracy, the International Air Transport Associ- ation shall not be held responsible for any loss or damage caused by errors, omissions, misprints or misinterpretation of the contents hereof. Fur- thermore, the International Air Transport Asso- ciation expressly disclaims any and all liability to any person or entity, whether a purchaser of this publication or not, in respect of anything done or omitted, and the consequences of anything done or omitted, by any such person or entity in reliance on the contents of this publication. Opinions expressed in advertisements ap- pearing in this publication are the advertiser’s opinions and do not necessarily reflect those of IATA. The mention of specific companies or products in advertisement does not im- ply that they are endorsed or recommended by IATA in preference to others of a similar na- ture which are not mentioned or advertised. © International Air Transport Association. All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, recast, reformatted or trans- mitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage and retrieval sys- tem, without the prior written permission from: Deputy Director General International Air Transport Association 33, Route de l’Aéroport 1215 Geneva 15 Airport Switzerland World Air Transport Statistics, Plus Edition 2021 ISBN 978-92-9264-350-8 © 2021 International Air Transport Association. -

Running Head: E-COMMERCE at YUNNAN LUCKY AIR 1 E

Running Head: E-COMMERCE AT YUNNAN LUCKY AIR 1 E-COMMERCE AT YUNNAN LUCKY AIR Jeremy Callinan University of the People May 13, 2019 E-COMMERCE AT YUNNAN LUCKY AIR 2 Abstract A cost-centered business strategy can be a key tactic for Yunnan Lucky Air to move forward as a profitable firm, and differentiate them amongst their competitors. Yunnan can use these tactics to differentiate themselves and support a cost-focused strategy developed in this paper. These tactics will be implemented within the scope of ecommerce as part of Yunnan’s overall strategy, and integrate with their marketing and operations plans. Definitions and supporting research will be included, including solutions and strategies for implementation. Yunnan has a unique situation it It’s heavily regulated competitive landscape in China, but opportunities are available, in being th low cost leader in a growing, technologically emerging nation. E-COMMERCE AT YUNNAN LUCKY AIR 3 Cost-focused strategy at Yunnan Lucky Air Lucky Air had grown into a US$104.3 million (RMB720 million) low-cost airline in only four years, serving domestic routes from its hub in Kunming, the capital of southwestern China’s Yunnan province (Berenguer 2008), later expanding to over 14 international routes (Kon 2017). The Chinese airline industry is heavily regulated, limiting flexibility for new airlines. Nonetheless, new low-cost competitors have been blossoming, and Lucky Air has been searching for additional competitive advantages. One option was to focus on e-commerce, a growing market in Chinese communities (Berenguer 2008). Lucky Air’s IT operation was backed by Hainan Airlines, which had one of the most advanced web portals in the Chinese airline industry. -

Hainan Airlines' Strategy in the China-Europe Market

Hainan Airlines’ Strategy in the China-Europe Market Driven by China’s Secondary Hubs’ Expansion Jianfeng SUN May, 2018 HNA Aviation HNA Aviation Totally there are 11 airlines within HNA Group in Mainland China, which include 2 full service airlines, Hainan and Beijing Capital Airlines, and 7 low-cost carriers. Full service network airline, global network, quality brand. HU Hainan Airlines Tianjin based airline, premium long-haul services. GS Tianjin Airlines JD Beijing Capital Airlines Beijing based full service airline, Beijing’s new airport. FU Fuzhou Airlines Fuzhou based low cost carrier. PEK Beijing URC Urumqi UQ Urumqi Airlines Urumqi based airline. XIY Xi’an TSN Tianjin PN West Air Chongqing based low cost carrier. PVG Shanghai CKG Chongqing 8L Lucky Air Kunming based low cost carrier. KWL Guilin FOC Fuzhou Nanning based airline. KMG Kunming GX Beibu Gulf Airlines NNG Nanning Y8 Suparna Airlines Shanghai based airline. GT Air Guilin HAK Haikou Guilin based airline, travel & tourism market. 9H Air Changan Xi’an based low cost carrier. International Network The latest data indicating the expanding international network of airlines within HNA group in Mainland China, currently covers 72 international & regional destinations,ofwhich29 are intercontinental destinations, with 100 international & regional routes across Asia, North America, Europe as well as Oceania. In 2017, four major airlines within HNA group, Hainan Airlines, Beijing Capital Airlines, Tianjin Airlines as well as Lucky Air, have totally received 17 wide-bodied aircrafts -

Airlines Codes

Airlines codes Sorted by Airlines Sorted by Code Airline Code Airline Code Aces VX Deutsche Bahn AG 2A Action Airlines XQ Aerocondor Trans Aereos 2B Acvilla Air WZ Denim Air 2D ADA Air ZY Ireland Airways 2E Adria Airways JP Frontier Flying Service 2F Aea International Pte 7X Debonair Airways 2G AER Lingus Limited EI European Airlines 2H Aero Asia International E4 Air Burkina 2J Aero California JR Kitty Hawk Airlines Inc 2K Aero Continente N6 Karlog Air 2L Aero Costa Rica Acori ML Moldavian Airlines 2M Aero Lineas Sosa P4 Haiti Aviation 2N Aero Lloyd Flugreisen YP Air Philippines Corp 2P Aero Service 5R Millenium Air Corp 2Q Aero Services Executive W4 Island Express 2S Aero Zambia Z9 Canada Three Thousand 2T Aerocaribe QA Western Pacific Air 2U Aerocondor Trans Aereos 2B Amtrak 2V Aeroejecutivo SA de CV SX Pacific Midland Airlines 2W Aeroflot Russian SU Helenair Corporation Ltd 2Y Aeroleasing SA FP Changan Airlines 2Z Aeroline Gmbh 7E Mafira Air 3A Aerolineas Argentinas AR Avior 3B Aerolineas Dominicanas YU Corporate Express Airline 3C Aerolineas Internacional N2 Palair Macedonian Air 3D Aerolineas Paraguayas A8 Northwestern Air Lease 3E Aerolineas Santo Domingo EX Air Inuit Ltd 3H Aeromar Airlines VW Air Alliance 3J Aeromexico AM Tatonduk Flying Service 3K Aeromexpress QO Gulfstream International 3M Aeronautica de Cancun RE Air Urga 3N Aeroperlas WL Georgian Airlines 3P Aeroperu PL China Yunnan Airlines 3Q Aeropostal Alas VH Avia Air Nv 3R Aerorepublica P5 Shuswap Air 3S Aerosanta Airlines UJ Turan Air Airline Company 3T Aeroservicios