Wyoming Law Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Laws of Pennsylvania

278 LAWS OF PENNSYLVANIA, appraisal given, in writing, by three (3) or more persons competent to give appraisal by reason of being a manufac- turer, dealer or user of such furniture or equipment. In no instance shall the school district pay more than the average of such appraised values. Necessary costs of securing such appraised values may be paid by the school district. Provided when appraised value is deter- mined to be more than one thousand dollars ($1,000), purchase may be made only after public notice has been given by advertisement once a week for three (3) weeks in not less than two (2) newspapers of general circula- tion. In any district where no newspaper is published, said notice may, in lieu of such publication, be posted in at least five (5) public places. Such advertisement shall specify the items to be purchased, name the vendor, state the proposed purchase price, and state the time and place of the public meeting at which such proposed purchase shall be considered by the board of school directors. APPROVED—The 8th day of June, A. D. 1961. DAVID L. LAWRENCE No. 163 AN ACT Amending the act of June 3, 1937 (P. L. 1225), entitled “An act concerning game and other wild birds and wild animals; and amending, revising, consolidating, and changing the law relating thereto,” removing provisions relating to archery preserves. The Game Law. The General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Penn- sylvania hereby enacts as follows: Section 317, act of June 3, 1937, Section 1. Section 317, act of June 3, 1937 (P. -

Department of Fish and Game Celebrates 130 Years of Serving

DepartmentDepartment ofof FishFish andand GameGame celebratescelebrates 130130 yyearearss ofof servingserving CalifCaliforniaornia .. .. .. n 1970, the Department of Fish and Game state hatching house is established at the turned 100 years old. At that time, a history University of California in Berkeley. ofI significant events over that 100 years was published. A frequently requested item, the 1871. First importation of fish-1,500 young history was updated in 1980, and now we have shad. Two full-time deputies (wardens) are another 20 years to add. We look forward to appointed, one to patrol San Francisco Bay seeing where fish and wildlife activities lead us and the other the Lake Tahoe area. in the next millennium. Editor 1872. The Legislature passes an act enabling 1849. California Territorial Legislature the commission to require fishways or in- adopts common law of England as the rule lieu hatcheries where dams or other in all state courts. Before this, Spanish and obstacles impede or prevent fish passage. then Mexican laws applied. Most significant legal incident was the Mexican 1878. The authority of the Fish government decree in 1830 that California Commission is expanded to include game mountain men were illegally hunting and as well as fish. fishing. Captain John Sutter, among others, had been responsible for enforcing 1879. Striped bass are introduced from New Mexican fish and game laws. Jersey and planted at Carquinez Strait. 1851. State of California enacts first law 1883. Commissioners establish a Bureau of specifically dealing with fish and game Patrol and Law Enforcement. Jack London matters. This concerned the right to take switches sides from oyster pirate to oysters and the protection of property Commission deputy. -

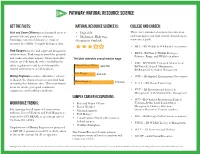

Natural Resource Science

Pathway: Natural Resource Science Get the Facts: Natural Resource Science is: College and Career: Fish and Game Officers patrol assigned areas to • High skill There are a number of options for education prevent fish and game law violations. • Medium to High wage and training beyond high school, depending on Investigate reports of damage to crops or Occupation Outlook: your career goals. property by wildlife. Compile biological data. • BYU – BS Wildlife & Wildlands Conservation Park Rangers protect and supervise designated outdoor areas. Park rangers patrol the grounds • BYUI – BS Plant & Wildlife Ecology— Fisheries, Range, and Wildlife emphases and make sure that campers, hikers and other The Utah statewide annual median wage: visitors are following the rules-- including fire • USU – BS Wildlife Ecology & Management; safety regulations-- and do not disrupt the Fish and Game Officer $49,760 BS Forest Ecology & Management; natural environment or fellow guests. BS Rangeland Ecology & Management Park Ranger $44,600 Mining Engineers conduct sub-surface surveys • WSU – BS Applied Environmenta Geosciences to identify the characteristics of potential land Mining Engineer or mining development sites. They may inspect $78,860 • U of U – BS Mining Engineering areas for unsafe geological conditions, equipment, and working conditions. • UVU – BS Environmental Science & Management; AAS Wildland Fire Management Sample Career Occupations: • SUU – BS Outdoor Recreation in Parks & Workforce Trends: • Fish and Game Officer Tourism—Public Lands Leadership & • Forest Worker Management, Outdoor Education, Job openings for all types of Conservation • Mining Engineer Outdoor Recreation Tourism emphases Officers, Forest Workers and Park Rangers is • Park Ranger • DSU – BS Biology—Natural Sciences emphasis expected to INCREASE at an average rate of • Conservation Officer with a state or 7% from 2014-2024. -

Historical Highlights Related to the Illinois Department of Natural Resources and Conservation in Illinois

Historical Highlights Related to the Illinois Department of Natural Resources and Conservation in Illinois 1492 - The first Europeans come to North America. 1600 - The land that is to become Illinois encompasses 21 million acres of prairie and 14 million acres of forest. 1680 - Fort Crevecoeur is constructed by René-Robert-Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle and his men on the bluffs above the Illinois River near Peoria. A few months later, the fort is destroyed. You can read more about the fort at http://www.ftcrevecoeur.org/history.html. 1682 - René-Robert-Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, and Henri de Tonti reach the mouth of the Mississippi River. Later, they build Fort St. Louis atop Starved Rock along the Illinois River. http://www.museum.state.il.us/muslink/nat_amer/post/htmls/arch_starv.html http://more.pjstar.com/peoria-history/ 1699 - A Catholic mission is established at Cahokia. 1703 - Kaskaskia is established by the French in southwestern Illinois. The site was originally host to many Native American villages. Kaskaskia became an important regional center. The Illinois Country, including Kaskaskia, came under British control in 1765, after the French and Indian War. Kaskaskia was taken from the British by the Virginia militia in the Revolutionary War. In 1818, Kaskaskia was named the first capital of the new state of Illinois. http://www.museum.state.il.us/muslink/nat_amer/post/htmls/arch_starv.html http://www.illinoisinfocus.com/kaskaskia.html 1717 - The original French settlements in Illinois are placed under the government of Louisiana. 1723 - Prairie du Rocher is settled. http://www.illinoisinfocus.com/prairie-du-rocher.html 1723 - Fort de Chartres is constructed. -

Wildlife Conservation and Management in Mexico

Peer Reviewed Wildlife Conservation and Management in Mexico RAUL VALDEZ,1 New Mexico State University,Department of Fishery and WildlifeSciences, MSC 4901, Las Cruces, NM 88003, USA JUAN C. GUZMAN-ARANDA,2 Colegio de Postgraduados, Campus San Luis Potos4 Iturbide 73, Salinas de Hidalgo, San Luis Potosl 78600, Mexico FRANCISCO J. ABARCA, Arizona Game and Fish, Phoenix, AZ 85023, USA LUIS A. TARANGO-ARAMBULA, Colegio de Postgraduados, Campus San Luis Potosl, Iturbide73, Salinas de Hidalgo, San Luis Potosl'78600, Mexico FERNANDO CLEMENTE SANCHEZ, Colegio de Postgraduados, Campus San Luis Potos,' Iturbide 73, Salinas de Hidalgo, San Luis Potosl' 78600, Mexico Abstract Mexico's wildlifehas been impacted by human land use changes and socioeconomic and political factors since before the Spanish conquest in 1521. Presently, it has been estimated that more than 60% of the land area has been severely degraded. Mexico ranksin the top 3 countries in biodiversity,is a plant and faunal dispersal corridor,and is a crucial element in the conservation and management of North American wildlife. Wildlifemanagement prerogatives and regulatory powers reside in the federal government with states relegated a minimum role. The continuous shifting of federal agencies responsible for wildlifemanagement with the concomitant lack of adequate federal funding has not permitted the establishment of a robust wildlifeprogram. In addition, wildlifeconservation has been furtherimpacted by a failureto establish landowner incentives, power struggles over user rights, resistance to change, and lack of trust and experience in protecting and managing Mexico's wildlife. We believe future strategies for wildlifeprograms must take into account Mexico's highly diversifiedmosaic of ecosystems, cultures, socioeconomic levels, and land tenure and political systems. -

Association of Midwest Fish & Game Law

ASSOCIATION OF MIDWEST FISH & GAME LAW ENFORCEMENT OFFICERS EST. 1944 ANNUAL AGENCY REPORTS 2019 ASSOCIATION OF MIDWEST FISH & GAME LAW ENFORCEMENT OFFICERS ALBERTA COLORADO INDIANA IOWA MICHIGAN MINNESOTA MISSOURI NORTH DAKOTA OHIO OKLAHOMA SASKATCHEWAN SOUTH DAKOTA TEXAS WISCONSIN Association of Midwest Fish and Game Law Enforcement Officers 2020 Agency Report State/Province: Alberta Fish and Wildlife Enforcement Branch Submitted by: Supt. Miles Grove Date: May 15, 2020 based on a ‘closest car’ policy. Once the Training Issues emergency is handled and the police are able to Describe any new or innovative training programs or assume total control, fish and wildlife officers will techniques which have been recently developed, revert to core mandated conservation enforcement implemented or are now required. duties. Unique Cross Boundary or Cooperative, The branch has postponed mandatory re- Enforcement Efforts certifications and in-service training due to COVID-19 restrictions. In Alberta, we now have the go ahead to Describe any Interagency, interstate, international, resume some training with strict protocols in state/tribal, or other cross jurisdictional enforcement accordance to Alberta Health Services. The Western efforts (e.g. major Lacey Act investigations, progress Conservation Law Enforcement Academy is with Wildlife Violator Compacts, improvements in postponed until September 2020 and may be interagency communication (WCIS), etc.) differed to May 2021 based on the lack of recruitment in western Canada. The Government of Special Investigations Section – Major Investigations Alberta has announced that fish and wildlife officers and Intelligence Unit (MIIU) will be assisting the RCMP (Provincial Police) with response to priority one and two emergencies in rural The Special Investigations Section is the designated areas. -

Chapter 13 Environmental Protection and Natural

WISCONSIN LEGISLATOR BRIEFING BOOK 2019-20 CHAPTER 13 ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AND NATURAL RESOURCES Rachel Letzing, Principal Attorney, and Anna Henning, Senior Staff Attorney Wisconsin Legislative Council TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................. 1 NAVIGABLE WATER AND WETLANDS .................................................................................. 1 The Public Trust Doctrine ........................................................................................................ 1 Navigable Water Regulations .................................................................................................. 2 Wetlands Regulation and Mitigation ....................................................................................... 3 Shoreland Zoning ..................................................................................................................... 5 Water Pollution Discharge Permits ......................................................................................... 6 Nonpoint Source Water Pollution ............................................................................................ 6 AIR POLLUTION CONTROL ................................................................................................. 7 SOLID WASTE AND RECYCLING .......................................................................................... 8 Solid Waste Disposal ............................................................................................................... -

The Year in Video Game Law

Science and Technology Law Review Volume 15 Number 2 Article 15 2012 The Year in Video Game Law W. Keith Robinson Southern Methodist University, Dedman School of Law, [email protected] Xuan-Thao Nguyen Indiana University Robert H. McKinney School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/scitech Part of the Computer Law Commons, Intellectual Property Law Commons, Internet Law Commons, and the Science and Technology Law Commons Recommended Citation W. Keith Robinson & Xuan-Thao Nguyen, The Year in Video Game Law, 15 SMU SCI. & TECH. L. REV. 127 (2012) https://scholar.smu.edu/scitech/vol15/iss2/15 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Science and Technology Law Review by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. The Year in Video Game Law Speaker: Professor W. Keith Robinson* INTRODUCTION BY PROFESSOR XUAN-THAO NGUYEN, SMU DEDMAN SCHOOL OF LAW: Professor Nguyen: Good morning, I am so pleased to be able to hold this pamphlet of the past year's cases in my hands. Every year at this sympo- sium you get a copy of the cases from the previous year. This is the result of hard work from law students. And for this particular year-the review of 2011 cases-two of my best students, Ken Jordan and Robert Wilkinson, put numerous hours into preparing this packet. There is something special about law students in general. -

Biodiversity and Wildlife Law

Essential Readings in Environmental Law IUCN Academy of Environmental Law (www.iucnael.org) BIODIVERSITY AND WILDLIFE LAW Erika J. Techera, The University of Western Australia, Australia Overview of Key Scholarships Emergence of wildlife conservation and biodiversity law 1. Hornaday, W.T., Our Vanishing Wildlife: Its Extermination and Preservation (Charles Scriber’s Sons 1913); 2. Scarff, J.E., ‘The international management of whales, dolphins and porpoises: An interdisciplinary assessment’ (1977) 6(2) Ecology Law Quarterly 323-427; and 3. Snape (III), W. J., Biodiversity and the Law, Island Press, 1996. Focusing on wildlife and biodiversity law 4. Cirelli, M.T., Legal Trends in Wildlife Management (FAO 2002); 5. Bowman, M., P. Davies, and C. Redgwell, Lyster’s International Wildlife Law, (2nd edn, Cambridge University Press 2010); 6. Freyfogle, E.T, and D. D. Goble, Wildlife Law: A Primer, (Island Press 2012); 7. Bilderbeek, S., (ed), Biodiversity and International Law (IOS Press, 1992); and 8. Jeffery, M.I., J. Firestone, and K. Bubna-Litic (Eds) Biodiversity Conservation, Law and Livelihoods: Bridging the North-South Divide (IUCN 2008). Specific contexts, critical and cross-cutting Issues 9. Oldfield, S., (ed), The Trade in Wildlife: Regulation for Conservation: Regulation for Conservation, (Earthscan 2003); 10. Morgera, E., Wildlife law and the empowerment of the poor (Food and Agriculture Organization 2011); 11. Philippopoulos-Mihalopoulos, A., (ed), Law and Ecology: New Environmental Foundations, (Routledge, 2011); and 12. McManis, C.R., (ed), Biodiversity and the Law: Intellectual Property, Biotechnology and Traditional Knowledge (Earthscan, 2012). Background The conservation of living natural resources has ancient origins. It is clear that many Indigenous and traditional communities did, and continue to, conserve and manage wildlife and natural resources. -

Wildlife Administration in Alaska, an Historic Sketch

February 1, 1965 Page 1 WILDLIFE ADHINISTRATION IN ALASKA AN HISTORIC SKETCH by J. 1/J. Brooks The abundant and varied vJildlife resources, which sustained the aboriginal population this vast region, attracted and supported the Russian colonization of AlasJ.:::a. This Russian era ·was marJ<::ed by excessive early exploita·tion of the more valuable fur bearing animals followed by the imposition of conservation measures and an orderly program of controlled harvest and restoration, particularly of the fur seals and sea otter. The years following the purchase of Alaska by t;he United States 1t7itnessed again the ruthless exploitation of the more valuable fur animals negating benefits the application of con servation measures by the Russians. The big and small game animals which had no export value "~;Jere nonetheless subjected ·to exploitation for subsistence purposes. Uith the exception of fur seals and sea otters, no legal restraints v1ere imposed during the 19th Century; the terrestrial stocJ<:s of v1ildlife generally were thought capable of sus taining the demands on them. Treasury Department agents, primarily concerned with seals and sea otters, first e~~pressed formal concern over other game 2 species in 1895, by recommending an October to April closed season on fur bearing animals. It was also recommended that this closed season embrace deer and mountain sheep, that there be a prohibition on the exportation of deer sJdns the territory, and that the use of poison prohibited. 1 expression of concern for the wel of fur and game animals was undoubtedly based more on observation of waste ful practices than on an actual diminution animal numbers. -

Fish and Game Commission

REGULATORY AGENCY ACTION allowed to continue tankering shipments area does not qualify for ecological re- liability owed to the state of California by (about one tanker trip per week) until Jan- serve status for harbor seals because they leaking storage tank owners who have de- uary 1, 1996. After that date, Chevron and are neither endangered nor threatened and clared bankruptcy. The Commission de- the other offshore oil producers near Santa do not depend upon habitat of Seal Rock nied Hill's petition, simultaneously assert- Barbara (Texaco and Exxon) will have to for their survival; and other less restrictive ing that it lacks authority to adopt the ship the oil by pipeline. From a group of alternatives are available to discourage proposed regulations because the dis- pipeline alternatives (including construc- public disturbance of seals when they charge of liquid waste that will or could tion of a new pipeline), the oil producers "haul out" onto the rock. However, based affect the quality of the surface or under- have selected the existing All American on expert testimony that the area may be ground water resources of the state is pri- Pipeline Company (AAPC); Commission a rookery and the public's presence may marily within the jurisdiction of the Water staff reported that the implementation of adversely impact seals during breeding Resources Control Board, and that the the AAPC alternative would require con- season, the permit prohibits swimming, proposed regulations would duplicate ex- necting a final segment of pipeline to the body surfing, snorkeling, scuba diving, isting Coastal Commission authority al- refineries in Los Angeles. -

Human Behavior Aspects of Fish and Wildlife Conservation an Annotated Bibliography

1973 USDA Forest Service General Technical Report PNW-4 This file was created by scanning the printed publication. Text errors identified by the software have been corrected; however, some errors may remain. HUMAN BEHAVIOR ASPECTS OF FISH AND WILDLIFE CONSERVATION AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY DALE R. POTTER KATHRYN M. SHARPE JOHN C. HENDEE Pacific Northwest Forest and Range Experiment Station U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service Portland, Oregon Abstract The bibliography covers nonbiological or human behavior aspects of fish and wildlife conservation including sportsman characteristics, safety, law enforcement, professional and sportsman education, nonconsumptive uses, economics, and his- tory. There are 995 references from 218 different sources. Also included are a list of reference sources used, an author index, and keywords, along with a keyword index. KEYWORDS: Recreation, wildlife, hunting, fishing, bibliography. Dale R. Potter is a Social Scientist with the Wildland Recreation Research Project of the Pacific Northwest Forest and Range Experiment Station. Kathryn M. Sharpe is a University of Washington student and a Recreation Research Technician cooperating with the Pacific Northwest Forest and Range Experiment Station, John c. Hendee is Wildland Recreation Research Project Leader for the Pacific Northwest Forest and Range Experiment Station. USDA FOREST SERVICE General Technical Report PNW-4 HUMAN BEHAVIOR ASPECTS OF FISH AND WILDLIFE CONSERVATION An Annotated Bibliography Dale R. Potter Kathryn M. Sharpe John C. Hendee 1973 CALIFORNIA RESOURCES AGENCY LlBRARY Resources Building, Room 117 1416 - 9th Str ee t Scramemto, California 95814 Pacific Northwest Forest and Range Experiment Station with financial assistance from The Wildlife Management Institute and American Petroleum Institute Robert E.