Why Private Game Reserves Offer a Chance to Save the Sport of Hunting and Conservation Practices

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Angolan Giraffe (Giraffa Camelopardalis Ssp

Angolan Giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis ssp. angolensis) Appendix 1: Historical and recent geographic range and population of Angolan Giraffe G. c. angolensis Geographic Range ANGOLA Historical range in Angola Giraffe formerly occurred in the mopane and acacia savannas of southern Angola (East 1999). According to Crawford-Cabral and Verissimo (2005), the historic distribution of the species presented a discontinuous range with two, reputedly separated, populations. The western-most population extended from the upper course of the Curoca River through Otchinjau to the banks of the Kunene (synonymous Cunene) River, and through Cuamato and the Mupa area further north (Crawford-Cabral and Verissimo 2005, Dagg 1962). The intention of protecting this western population of G. c. angolensis, led to the proclamation of Mupa National Park (Crawford-Cabral and Verissimo 2005, P. Vaz Pinto pers. comm.). The eastern population occurred between the Cuito and Cuando Rivers, with larger numbers of records from the southeast corner of the former Mucusso Game Reserve (Crawford-Cabral and Verissimo 2005, Dagg 1962). By the late 1990s Giraffe were assumed to be extinct in Angola (East 1999). According to Kuedikuenda and Xavier (2009), a small population of Angolan Giraffe may still occur in Mupa National Park; however, no census data exist to substantiate this claim. As the Park was ravaged by poachers and refugees, it was generally accepted that Giraffe were locally extinct until recent re-introductions into southern Angola from Namibia (Kissama Foundation 2015, East 1999, P. Vaz Pinto pers. comm.). BOTSWANA Current range in Botswana Recent genetic analyses have revealed that the population of Giraffe in the Central Kalahari and Khutse Game Reserves in central Botswana is from the subspecies G. -

Selous Game Reserve Tanzania

SELOUS GAME RESERVE TANZANIA Selous contains a third of the wildlife estate of Tanzania. Large numbers of elephants, buffaloes, giraffes, hippopotamuses, ungulates and crocodiles live in this immense sanctuary which measures almost 50,000 square kilometres and is relatively undisturbed by humans. The Reserve has a wide variety of vegetation zones, from forests and dense thickets to open wooded grasslands and riverine swamps. COUNTRY Tanzania NAME Selous Game Reserve NATURAL WORLD HERITAGE SITE 1982: Inscribed on the World Heritage List under Natural Criteria ix and x. STATEMENT OF OUTSTANDING UNIVERSAL VALUE The UNESCO World Heritage Committee issued the following Statement of Outstanding Universal Value at the time of inscription: Brief Synthesis The Selous Game Reserve, covering 50,000 square kilometres, is amongst the largest protected areas in Africa and is relatively undisturbed by human impact. The property harbours one of the most significant concentrations of elephant, black rhinoceros, cheetah, giraffe, hippopotamus and crocodile, amongst many other species. The reserve also has an exceptionally high variety of habitats including Miombo woodlands, open grasslands, riverine forests and swamps, making it a valuable laboratory for on-going ecological and biological processes. Criterion (ix): The Selous Game Reserve is one of the largest remaining wilderness areas in Africa, with relatively undisturbed ecological and biological processes, including a diverse range of wildlife with significant predator/prey relationships. The property contains a great diversity of vegetation types, including rocky acacia-clad hills, gallery and ground water forests, swamps and lowland rain forest. The dominant vegetation of the reserve is deciduous Miombo woodlands and the property constitutes a globally important example of this vegetation type. -

Laws of Pennsylvania

278 LAWS OF PENNSYLVANIA, appraisal given, in writing, by three (3) or more persons competent to give appraisal by reason of being a manufac- turer, dealer or user of such furniture or equipment. In no instance shall the school district pay more than the average of such appraised values. Necessary costs of securing such appraised values may be paid by the school district. Provided when appraised value is deter- mined to be more than one thousand dollars ($1,000), purchase may be made only after public notice has been given by advertisement once a week for three (3) weeks in not less than two (2) newspapers of general circula- tion. In any district where no newspaper is published, said notice may, in lieu of such publication, be posted in at least five (5) public places. Such advertisement shall specify the items to be purchased, name the vendor, state the proposed purchase price, and state the time and place of the public meeting at which such proposed purchase shall be considered by the board of school directors. APPROVED—The 8th day of June, A. D. 1961. DAVID L. LAWRENCE No. 163 AN ACT Amending the act of June 3, 1937 (P. L. 1225), entitled “An act concerning game and other wild birds and wild animals; and amending, revising, consolidating, and changing the law relating thereto,” removing provisions relating to archery preserves. The Game Law. The General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Penn- sylvania hereby enacts as follows: Section 317, act of June 3, 1937, Section 1. Section 317, act of June 3, 1937 (P. -

Confirmed Soc Reports List 2015-2016

Confirmed State of Conservation Reports for natural and mixed World Heritage sites 2015 - 2016 Nr Region Country Site Natural or Additional information mixed site 1 LAC Argentina Iguazu National Park Natural 2 APA Australia Tasmanian Wilderness Mixed 3 EURNA Belarus / Poland Bialowieza Forest Natural 4 LAC Belize Belize Barrier Reef Reserve System Natural World Heritage in Danger 5 AFR Botswana Okavango Delta Natural 6 LAC Brazil Iguaçu National Park Natural 7 LAC Brazil Cerrado Protected Areas: Chapada dos Veadeiros and Natural Emas National Parks 8 EURNA Bulgaria Pirin National Park Natural 9 AFR Cameroon Dja Faunal Reserve Natural 10 EURNA Canada Gros Morne National Park Natural 11 AFR Central African Republic Manovo-Gounda St Floris National Park Natural World Heritage in Danger 12 LAC Costa Rica / Panama Talamanca Range-La Amistad Reserves / La Amistad Natural National Park 13 AFR Côte d'Ivoire Comoé National Park Natural World Heritage in Danger 14 AFR Côte d'Ivoire / Guinea Mount Nimba Strict Nature Reserve Natural World Heritage in Danger 15 AFR Democratic Republic of the Congo Garamba National Park Natural World Heritage in Danger 16 AFR Democratic Republic of the Congo Kahuzi-Biega National Park Natural World Heritage in Danger 17 AFR Democratic Republic of the Congo Okapi Wildlife Reserve Natural World Heritage in Danger 18 AFR Democratic Republic of the Congo Salonga National Park Natural World Heritage in Danger 19 AFR Democratic Republic of the Congo Virunga National Park Natural World Heritage in Danger 20 AFR Democratic -

Data Collection Survey on Forest Conservation in Southern Africa for Addressing Climate Change

DATA COLLECTION SURVEY ON FOREST CONSERVATION IN SOUTHERN AFRICA FOR ADDRESSING CLIMATE CHANGE Final Report April 2013 Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) RECS International Inc. Remote Sensing Technology Center of Japan MAP OF SOUTHERN AFRICA (provided by SADC) Data Collection Survey on Forest Conservation in Southern Africa for Addressing Climate Change Final Report DATA COLLECTION SURVEY ON FOREST CONSERVATION IN SOUTHERN AFRICA FOR ADDRESSING CLIMATE CHANGE Final Report Table of Contents Executive Summary ......................................................................................................................... S-1 Part I: Main Report Chapter 1 Survey Outline .............................................................................................................. 1-1 1.1 Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 1-1 1.2 Objectives and Expected Outputs ......................................................................................... 1-2 1.3 Survey Scope ........................................................................................................................ 1-2 1.4 Structure of Report ............................................................................................................... 1-3 Chapter 2 Current Status of Forest Resources and Management and International Cooperation in Southern Africa .................................................................................. 2-1 -

Department of Fish and Game Celebrates 130 Years of Serving

DepartmentDepartment ofof FishFish andand GameGame celebratescelebrates 130130 yyearearss ofof servingserving CalifCaliforniaornia .. .. .. n 1970, the Department of Fish and Game state hatching house is established at the turned 100 years old. At that time, a history University of California in Berkeley. ofI significant events over that 100 years was published. A frequently requested item, the 1871. First importation of fish-1,500 young history was updated in 1980, and now we have shad. Two full-time deputies (wardens) are another 20 years to add. We look forward to appointed, one to patrol San Francisco Bay seeing where fish and wildlife activities lead us and the other the Lake Tahoe area. in the next millennium. Editor 1872. The Legislature passes an act enabling 1849. California Territorial Legislature the commission to require fishways or in- adopts common law of England as the rule lieu hatcheries where dams or other in all state courts. Before this, Spanish and obstacles impede or prevent fish passage. then Mexican laws applied. Most significant legal incident was the Mexican 1878. The authority of the Fish government decree in 1830 that California Commission is expanded to include game mountain men were illegally hunting and as well as fish. fishing. Captain John Sutter, among others, had been responsible for enforcing 1879. Striped bass are introduced from New Mexican fish and game laws. Jersey and planted at Carquinez Strait. 1851. State of California enacts first law 1883. Commissioners establish a Bureau of specifically dealing with fish and game Patrol and Law Enforcement. Jack London matters. This concerned the right to take switches sides from oyster pirate to oysters and the protection of property Commission deputy. -

Ramsar Information Sheet

Ramsar Information Sheet Text copy-typed from the original document. 1. Date this sheet was completed: 20.11.1996 2. Country: Botswana 3. Name of wetland: The Okavango Delta System 4. Geographical co-ordinates: The Okavango Delta System lies between Longitudes 21 degrees 45 minutes East and 23 degrees 53 minutes East; and Latitudes 18 degrees 15 minutes South and 20 degrees 45 minutes South. It includes the Okavango River, commonly referred to as the Pan handle; the entire Okavango Delta; Lake Ngami; and parts of the Kwando and Linyanti River systems that fall west of the western boundary of the Chobe National Park. The entire area is as depicted on the attached map. 5. Altitude: Generally between 930 metres and 1000 metres above sea level. 6. Area: Approximately 68 640 km² (6 864 000 hectares) 7. Overview Three main features characterise the region, the Okavango, the Kwando and Linyanti river system connected to the Okavango Delta through the Selinda spillway and the intervening and surrounding dryland areas. These features are located within the Okavango rift, a geological structure subject to tectonis control and infilled with Kahalari Group sediments, principally sand, up to 300 metres thick. The Delta is the most important of the above named features. It is an inland delta in a semi arid region in which inflow fluctuations result in large fluctuations in flooded area (10,000 - 16,000 km²), which is comprised of permanent swamp, seasonal swamp and intermittently flooded areas. Similar flooding takes place in the Kwando/Linyanti river system. This leads to high seasonal concentrations of birdlife and wildlife, giving the area a very high tourism potential. -

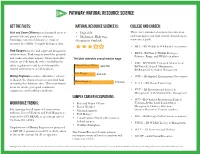

Natural Resource Science

Pathway: Natural Resource Science Get the Facts: Natural Resource Science is: College and Career: Fish and Game Officers patrol assigned areas to • High skill There are a number of options for education prevent fish and game law violations. • Medium to High wage and training beyond high school, depending on Investigate reports of damage to crops or Occupation Outlook: your career goals. property by wildlife. Compile biological data. • BYU – BS Wildlife & Wildlands Conservation Park Rangers protect and supervise designated outdoor areas. Park rangers patrol the grounds • BYUI – BS Plant & Wildlife Ecology— Fisheries, Range, and Wildlife emphases and make sure that campers, hikers and other The Utah statewide annual median wage: visitors are following the rules-- including fire • USU – BS Wildlife Ecology & Management; safety regulations-- and do not disrupt the Fish and Game Officer $49,760 BS Forest Ecology & Management; natural environment or fellow guests. BS Rangeland Ecology & Management Park Ranger $44,600 Mining Engineers conduct sub-surface surveys • WSU – BS Applied Environmenta Geosciences to identify the characteristics of potential land Mining Engineer or mining development sites. They may inspect $78,860 • U of U – BS Mining Engineering areas for unsafe geological conditions, equipment, and working conditions. • UVU – BS Environmental Science & Management; AAS Wildland Fire Management Sample Career Occupations: • SUU – BS Outdoor Recreation in Parks & Workforce Trends: • Fish and Game Officer Tourism—Public Lands Leadership & • Forest Worker Management, Outdoor Education, Job openings for all types of Conservation • Mining Engineer Outdoor Recreation Tourism emphases Officers, Forest Workers and Park Rangers is • Park Ranger • DSU – BS Biology—Natural Sciences emphasis expected to INCREASE at an average rate of • Conservation Officer with a state or 7% from 2014-2024. -

Travel Specialists

Jordan Harvey, a South America specialist, plans treks in the Andes passing alpaca- and llama-filled pastures. Te more unpredict- able our natural and political land- scapes become, the more we feel the urge to visit places untouched by the news cycle. So, as we continue to support and keep a close watch on those areas hit hardest by a rash of hurri- canes, fires, and foreign- policy blunders, we’re craving the kind of life- and perspec- tive-changing travel that’s made all the more magical when planned by the pros—no matter how fearless and self- sufcient we some- times feel. Because surviving in, say, the Bolivian jungle one day and meeting with the hottest artists in Lima the next re- quires both grit and access—to say nothing of a netork of on-the-ground 2017 know-how that you quite literally can’t live without in some T R AVEL SPECIALISTS places. Here are the experts, fixers, and experience makers you’ll want in your foxhole. JérômeGalland Photographby 46 Condé Nast Traveler / 12.17 by PAUL BRADY and CHRISTINE CANTERA TRAVEL SPECIALISTS Forces officers, Ryan Hilton archaeologists, chefs, AuthentEscapes AFRICA AND THE and other insiders. He’s planned photogra- phy workshops in the MIDDLE EAST MOROCCO Michael Diamond bush, connected travel- Cobblestone Private ers with antipoaching Travel teams, and coordinated His travelers meet with a 10-day, 62-mile walk- women’s rights NGOs ing safari through raw in the Ourika Valley, get wilderness. CENTR AL, EASTER N, the best rooms at Teresa Sullivan AND SOUTHER N AFR ICA in-demand riads in Mango African Safaris Cherri Briggs Marrakech, and do tast- Sullivan knows which Explore, Inc. -

Scf Pan Sahara Wildlife Survey

SCF PAN SAHARA WILDLIFE SURVEY PSWS Technical Report 12 SUMMARY OF RESULTS AND ACHIEVEMENTS OF THE PILOT PHASE OF THE PAN SAHARA WILDLIFE SURVEY 2009-2012 November 2012 Dr Tim Wacher & Mr John Newby REPORT TITLE Wacher, T. & Newby, J. 2012. Summary of results and achievements of the Pilot Phase of the Pan Sahara Wildlife Survey 2009-2012. SCF PSWS Technical Report 12. Sahara Conservation Fund. ii + 26 pp. + Annexes. AUTHORS Dr Tim Wacher (SCF/Pan Sahara Wildlife Survey & Zoological Society of London) Mr John Newby (Sahara Conservation Fund) COVER PICTURE New-born dorcas gazelle in the Ouadi Rimé-Ouadi Achim Game Reserve, Chad. Photo credit: Tim Wacher/ZSL. SPONSORS AND PARTNERS Funding and support for the work described in this report was provided by: • His Highness Sheikh Mohammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan, Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi • Emirates Center for Wildlife Propagation (ECWP) • International Fund for Houbara Conservation (IFHC) • Sahara Conservation Fund (SCF) • Zoological Society of London (ZSL) • Ministère de l’Environnement et de la Lutte Contre la Désertification (Niger) • Ministère de l’Environnement et des Ressources Halieutiques (Chad) • Direction de la Chasse, Faune et Aires Protégées (Niger) • Direction des Parcs Nationaux, Réserves de Faune et de la Chasse (Chad) • Direction Générale des Forêts (Tunis) • Projet Antilopes Sahélo-Sahariennes (Niger) ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Sahara Conservation Fund sincerely thanks HH Sheikh Mohamed bin Zayed Al Nahyan, Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi, for his interest and generosity in funding the Pan Sahara Wildlife Survey through the Emirates Centre for Wildlife Propagation (ECWP) and the International Fund for Houbara Conservation (IFHC). This project is carried out in association with the Zoological Society of London (ZSL). -

Impact Report 2017–18 in This Era When the Fight Against Rhino Poaching Is Becoming More Modernised, We Tend to Neglect the Importance of the Human Element

Save the Rhino International Impact Report 2017–18 In this era when the fight against rhino poaching is becoming more modernised, we tend to neglect the importance of the human element. There is a critical need to look after our most important assets: our staff. All the technology in the world means nothing without the correct application of the boots on the ground, and that’s where the support of Save the Rhino and its donors has been so helpful. Eduard Goosen, Conservation Manager, uMkhuze Game Reserve, South Africa 2 OUR VISION A message from our CEO All five rhino species Save the Rhino started with adventure: motor-biking from thriving in the wild Nairobi to London for a ‘rhino scramble’ and climbing Mt Kilimanjaro to raise vital funds for OUR MISSION conservation programmes that were just beginning Collaborating with partners to to come out of an intense two decades of poaching. Since Save the Rhino was registered as a charity in support endangered rhinos in 1994, we have continued the adventure theme with Africa and Asia supporters taking on challenges of all shapes and sizes. All for one reason: to help rhinos. I’m proud to say that during the past year we have been able to give out our biggest sum of grants to date, totalling more than £2,000,000 OUR STRATEGIES and supporting 27 programmes across Africa and Asia. These funds have been used – among other things – to purchase boots, binoculars Saving rhinos and beds for rangers, as well as essential anti-poaching and 1 monitoring equipment so that wherever a rhino is, it can be protected. -

Historical Highlights Related to the Illinois Department of Natural Resources and Conservation in Illinois

Historical Highlights Related to the Illinois Department of Natural Resources and Conservation in Illinois 1492 - The first Europeans come to North America. 1600 - The land that is to become Illinois encompasses 21 million acres of prairie and 14 million acres of forest. 1680 - Fort Crevecoeur is constructed by René-Robert-Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle and his men on the bluffs above the Illinois River near Peoria. A few months later, the fort is destroyed. You can read more about the fort at http://www.ftcrevecoeur.org/history.html. 1682 - René-Robert-Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, and Henri de Tonti reach the mouth of the Mississippi River. Later, they build Fort St. Louis atop Starved Rock along the Illinois River. http://www.museum.state.il.us/muslink/nat_amer/post/htmls/arch_starv.html http://more.pjstar.com/peoria-history/ 1699 - A Catholic mission is established at Cahokia. 1703 - Kaskaskia is established by the French in southwestern Illinois. The site was originally host to many Native American villages. Kaskaskia became an important regional center. The Illinois Country, including Kaskaskia, came under British control in 1765, after the French and Indian War. Kaskaskia was taken from the British by the Virginia militia in the Revolutionary War. In 1818, Kaskaskia was named the first capital of the new state of Illinois. http://www.museum.state.il.us/muslink/nat_amer/post/htmls/arch_starv.html http://www.illinoisinfocus.com/kaskaskia.html 1717 - The original French settlements in Illinois are placed under the government of Louisiana. 1723 - Prairie du Rocher is settled. http://www.illinoisinfocus.com/prairie-du-rocher.html 1723 - Fort de Chartres is constructed.