The Year in Video Game Law

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Laws of Pennsylvania

278 LAWS OF PENNSYLVANIA, appraisal given, in writing, by three (3) or more persons competent to give appraisal by reason of being a manufac- turer, dealer or user of such furniture or equipment. In no instance shall the school district pay more than the average of such appraised values. Necessary costs of securing such appraised values may be paid by the school district. Provided when appraised value is deter- mined to be more than one thousand dollars ($1,000), purchase may be made only after public notice has been given by advertisement once a week for three (3) weeks in not less than two (2) newspapers of general circula- tion. In any district where no newspaper is published, said notice may, in lieu of such publication, be posted in at least five (5) public places. Such advertisement shall specify the items to be purchased, name the vendor, state the proposed purchase price, and state the time and place of the public meeting at which such proposed purchase shall be considered by the board of school directors. APPROVED—The 8th day of June, A. D. 1961. DAVID L. LAWRENCE No. 163 AN ACT Amending the act of June 3, 1937 (P. L. 1225), entitled “An act concerning game and other wild birds and wild animals; and amending, revising, consolidating, and changing the law relating thereto,” removing provisions relating to archery preserves. The Game Law. The General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Penn- sylvania hereby enacts as follows: Section 317, act of June 3, 1937, Section 1. Section 317, act of June 3, 1937 (P. -

Department of Fish and Game Celebrates 130 Years of Serving

DepartmentDepartment ofof FishFish andand GameGame celebratescelebrates 130130 yyearearss ofof servingserving CalifCaliforniaornia .. .. .. n 1970, the Department of Fish and Game state hatching house is established at the turned 100 years old. At that time, a history University of California in Berkeley. ofI significant events over that 100 years was published. A frequently requested item, the 1871. First importation of fish-1,500 young history was updated in 1980, and now we have shad. Two full-time deputies (wardens) are another 20 years to add. We look forward to appointed, one to patrol San Francisco Bay seeing where fish and wildlife activities lead us and the other the Lake Tahoe area. in the next millennium. Editor 1872. The Legislature passes an act enabling 1849. California Territorial Legislature the commission to require fishways or in- adopts common law of England as the rule lieu hatcheries where dams or other in all state courts. Before this, Spanish and obstacles impede or prevent fish passage. then Mexican laws applied. Most significant legal incident was the Mexican 1878. The authority of the Fish government decree in 1830 that California Commission is expanded to include game mountain men were illegally hunting and as well as fish. fishing. Captain John Sutter, among others, had been responsible for enforcing 1879. Striped bass are introduced from New Mexican fish and game laws. Jersey and planted at Carquinez Strait. 1851. State of California enacts first law 1883. Commissioners establish a Bureau of specifically dealing with fish and game Patrol and Law Enforcement. Jack London matters. This concerned the right to take switches sides from oyster pirate to oysters and the protection of property Commission deputy. -

Download Case Study Zynga Inc

Case Study: For academic or private use only; all rights reserved May 2014 Supplement to the Treatise WOLFGANG RUNGE: TECHNOLOGY ENTREPRENEURSHIP How to access the treatise is given at the end of this document. Reference to this treatise will be made in the following form: [Runge:page number(s), chapters (A.1.1) or other chunks, such as tables or figures]. To compare the games business in the US and Germany to a certain degree references often ad- dress the case of the German firm Gameforge AG. For foundations of both the startups serial entrepreneurs played a key role. Wolfgang Runge Zynga, Inc. Table of Content Remarks Concerning the Market and Industry Environments ....................................................... 2 The Entrepreneur(s) .................................................................................................................... 3 The Business Idea, Opportunity and Foundation Process ............................................................ 5 Corporate Culture.................................................................................................................... 7 Market Entry, Expansion and Diversification ................................................................................ 9 Vision/Mission, Risks and Business Model ................................................................................ 11 Intellectual Property ................................................................................................................... 15 Key Metrics .............................................................................................................................. -

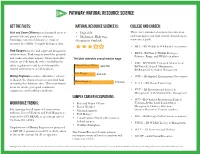

Natural Resource Science

Pathway: Natural Resource Science Get the Facts: Natural Resource Science is: College and Career: Fish and Game Officers patrol assigned areas to • High skill There are a number of options for education prevent fish and game law violations. • Medium to High wage and training beyond high school, depending on Investigate reports of damage to crops or Occupation Outlook: your career goals. property by wildlife. Compile biological data. • BYU – BS Wildlife & Wildlands Conservation Park Rangers protect and supervise designated outdoor areas. Park rangers patrol the grounds • BYUI – BS Plant & Wildlife Ecology— Fisheries, Range, and Wildlife emphases and make sure that campers, hikers and other The Utah statewide annual median wage: visitors are following the rules-- including fire • USU – BS Wildlife Ecology & Management; safety regulations-- and do not disrupt the Fish and Game Officer $49,760 BS Forest Ecology & Management; natural environment or fellow guests. BS Rangeland Ecology & Management Park Ranger $44,600 Mining Engineers conduct sub-surface surveys • WSU – BS Applied Environmenta Geosciences to identify the characteristics of potential land Mining Engineer or mining development sites. They may inspect $78,860 • U of U – BS Mining Engineering areas for unsafe geological conditions, equipment, and working conditions. • UVU – BS Environmental Science & Management; AAS Wildland Fire Management Sample Career Occupations: • SUU – BS Outdoor Recreation in Parks & Workforce Trends: • Fish and Game Officer Tourism—Public Lands Leadership & • Forest Worker Management, Outdoor Education, Job openings for all types of Conservation • Mining Engineer Outdoor Recreation Tourism emphases Officers, Forest Workers and Park Rangers is • Park Ranger • DSU – BS Biology—Natural Sciences emphasis expected to INCREASE at an average rate of • Conservation Officer with a state or 7% from 2014-2024. -

Hold Onto Your Horns: Zynga Launches Running with Friends for Worldwide Audiences

May 9, 2013 Hold Onto Your Horns: Zynga Launches Running With Friends for Worldwide Audiences Players to Show-Off Their Bullish Bravado as They Challenge Opponents in the Newest 'With Friends' Game Available Today Exclusively on iPhone, iPad, and iPod touch SAN FRANCISCO, May 9, 2013 (GLOBE NEWSWIRE) -- Zynga, (Nasdaq:ZNGA), the world's leading provider of social game services, today launched Running With Friends to global audiences on iPhone, iPad, and iPod touch. Running With Friends is a high-speed, 3D action-arcade game and the first truly social endless runner game. Players around the world can now stampede their way through the cobblestone streets of Pamplona, Spain, home to the annual Running of the Bulls Festival, as they try to outmaneuver, outrun, and outscore their friends. As the seventh title in the globally popular 'With Friends' franchise and Zynga's entrant to the runner category, Running With Friends brings a new level of social interaction and fun to the genre. The game includes beloved social elements such as turn- based competition with real-life friends and a chance to bullishly climb the leaderboards by jumping, bumping, and sliding through challenging game-play. Easy to play but tough to master, players compete with friends in three rounds to outrun their opponents by swiping their screen vertically and horizontally to dodge charging bulls and speeding cars, or even ride a bucking bull for bonuses. Players select their own in-game character and can choose to run as a ninja, ballerina, or a zombie. "We are committed to expanding Zynga's mobile portfolio to bring players the most fun, social, and accessible games to play with their friends," said Travis Boatman, Senior Vice President of Mobile at Zynga. -

PDF Download

Issue 01 – 2012 Journal –Peer Reviewed MELINDA JACOBS Flight 1337 [email protected] Click, click, click, click Zynga and the gamification of clicking Although the era of the social network game ofcially began with the launch of the Facebook Platform in 2007, it wasn’t until 2009 that social network games began to attract the spotlight of mainstream media with the runaway successes of several games. Not surprisingly, since that moment the online gaming industry has been fully occupied with discerning and attempting to replicate the elements that have made those Facebook games fruitful. Both academics and industry members have engaged in a hearty amount of discussion and speculation as to the reasons for the success seen by social network gaming, watching the evolution of the genre as companies have both emerged and retreated from the industry. Despite the large number of games appearing on Facebook by a variety of publishers and developers almost none have come close to meeting or bypass- ing the initial pace set by game developer Zynga. Over the course of just a few years, Zynga has built a company valued at over 15 billion USD with over 200 million monthly active users (MAU) of their games (Woo & Raice, 2011). The next closest game developer is EA at 55 million MAU. EA is one of the frst developers in the past three years to develop a game, The Sims Social with 28 million MAU, that has come close to average MAU counts—30 to 40 mil- lion—of the games released by Zynga (Appdata, 2011). What then is it about Zynga’s games in particular that make them so successful? In the discussion and literature addressing social network gaming and the reception and success of Zynga’s games in particular, three core features of their structural design stand out that are frequently referenced as reasons for the suc- cess of Zynga. -

Zynga Seeks New Harvest with Mobile Farmville Game 17 April 2014, by Glenn Chapman

Zynga seeks new harvest with mobile FarmVille game 17 April 2014, by Glenn Chapman "FarmVille really put social gaming on the map," Davies said. "It has stood the test of time." The new mobile version of the game was released globally in more than dozen languages. Since tens of millions of people still play "FarmVille" with friends at Facebook, the mobile version connects back to the leading social network. It also connects with Facebook rival Google+. However, the mobile version of the game gives people the option of playing FarmVille without friends for the first time in the franchise, according to Zynga vice president of games Jonathan Knight. A pedestrian walks by the Zynga headquarters on July 25, 2013 in San Francisco, California FarmVille is essentially what it sounds like, in that players feed livestock, nurture crops, craft goods and virtually tend to other aspects of country life. Social games pioneer Zynga on Thursday released In the mobile version, "we've added more ways for a version of the hit "FarmVille" tailored for players to team up together, help each other out smartphones and tablets in the hope of reaping a and even compete," Davies said. bumper crop of players. Bite-sized play The San Francisco-based game maker set on its heels by a shift away from desktop computers is Zynga has made a priority of adapting games for out to regain momentum with the mobile-format lifestyles increasingly centered on smartphones "Farmville 2: Country Escape" for iPhone, iPad and and tablets. The new game takes advantage of Android devices. -

Growth Opportunities for Online Games Beyond Facebook

Growth Opportunities for Online Games Beyond Facebook Philip Reisberger Chief Revenue Officer Games Developer Conference San Francisco Bigpoint at a Glance The Company The Figures Founded 2002 70 active games, 30 languages Number of Employees 900+ More than 250+ million users Over 1 billion daily transactions Key Titles Battlestar Galactica Online, Drakensang Industry Accolades Online, DarkOrbit, Farmerama European Business Awards 2011 Unity Awards 2011 Locations Investor Allstars Awards 2011 Hamburg (GER), Berlin (GER) Startup of the Century Award 2011 San Francisco (USA) European Games Awards 2011 Malta, Sao Paulo (BRA) Browser Game of the Year 2011 Paris (FRA), London (UK) Mashable Best Online Game 2010 International Business Award 2010 2 What Happened in 2011 3 Facebook Growth Penetration of Total Internet Audience Out of 2.1 Billion Internet Users Worldwide Source: CNET 4 Social Games Explosion Top 10 Facebook Games of 2011 1. GARDENS OF TIME (PLAYDOM) 2. THE SIMS SOCIAL (EA) 3. CITYVILLE (ZYNGA) 4. DOUBLEDOWN CASINO (DOUBLEDOWN ENTERTAINMENT) 5. INDIANA JONES ADVENTURE WORLD (ZYNGA) 6. WORDS WITH FRIENDS (ZYNGA) 7. BINGO BLITZ (BUFFALO STUDIOS) 8. EMPIRES & ALLIES (ZYNGA) 9. SLOTOMANIA-SLOT MACHINES (PLAYTIKA) 10. DIAMOND DASH (WOOGA) Source: Mashable 5 In Europe, Facebook is building a dedicated gaming team… Goal to replicate US gaming ecosystem More then 500 million downloads of Angry Birds across all platforms Angry Birds Rio won "Best Mobile App for Consumers" at Global Mobile Awards, "Best Mobile Game" at the Mobile Excellence Awards and "Best Mobile Game" at the Golden Joystick Awards. 185% User Growth in 2011 – Berlin Start Up #3 on Facebook 14 million (01/11) => 40 million MAU (01/12). -

Historical Highlights Related to the Illinois Department of Natural Resources and Conservation in Illinois

Historical Highlights Related to the Illinois Department of Natural Resources and Conservation in Illinois 1492 - The first Europeans come to North America. 1600 - The land that is to become Illinois encompasses 21 million acres of prairie and 14 million acres of forest. 1680 - Fort Crevecoeur is constructed by René-Robert-Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle and his men on the bluffs above the Illinois River near Peoria. A few months later, the fort is destroyed. You can read more about the fort at http://www.ftcrevecoeur.org/history.html. 1682 - René-Robert-Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, and Henri de Tonti reach the mouth of the Mississippi River. Later, they build Fort St. Louis atop Starved Rock along the Illinois River. http://www.museum.state.il.us/muslink/nat_amer/post/htmls/arch_starv.html http://more.pjstar.com/peoria-history/ 1699 - A Catholic mission is established at Cahokia. 1703 - Kaskaskia is established by the French in southwestern Illinois. The site was originally host to many Native American villages. Kaskaskia became an important regional center. The Illinois Country, including Kaskaskia, came under British control in 1765, after the French and Indian War. Kaskaskia was taken from the British by the Virginia militia in the Revolutionary War. In 1818, Kaskaskia was named the first capital of the new state of Illinois. http://www.museum.state.il.us/muslink/nat_amer/post/htmls/arch_starv.html http://www.illinoisinfocus.com/kaskaskia.html 1717 - The original French settlements in Illinois are placed under the government of Louisiana. 1723 - Prairie du Rocher is settled. http://www.illinoisinfocus.com/prairie-du-rocher.html 1723 - Fort de Chartres is constructed. -

Wildlife Conservation and Management in Mexico

Peer Reviewed Wildlife Conservation and Management in Mexico RAUL VALDEZ,1 New Mexico State University,Department of Fishery and WildlifeSciences, MSC 4901, Las Cruces, NM 88003, USA JUAN C. GUZMAN-ARANDA,2 Colegio de Postgraduados, Campus San Luis Potos4 Iturbide 73, Salinas de Hidalgo, San Luis Potosl 78600, Mexico FRANCISCO J. ABARCA, Arizona Game and Fish, Phoenix, AZ 85023, USA LUIS A. TARANGO-ARAMBULA, Colegio de Postgraduados, Campus San Luis Potosl, Iturbide73, Salinas de Hidalgo, San Luis Potosl'78600, Mexico FERNANDO CLEMENTE SANCHEZ, Colegio de Postgraduados, Campus San Luis Potos,' Iturbide 73, Salinas de Hidalgo, San Luis Potosl' 78600, Mexico Abstract Mexico's wildlifehas been impacted by human land use changes and socioeconomic and political factors since before the Spanish conquest in 1521. Presently, it has been estimated that more than 60% of the land area has been severely degraded. Mexico ranksin the top 3 countries in biodiversity,is a plant and faunal dispersal corridor,and is a crucial element in the conservation and management of North American wildlife. Wildlifemanagement prerogatives and regulatory powers reside in the federal government with states relegated a minimum role. The continuous shifting of federal agencies responsible for wildlifemanagement with the concomitant lack of adequate federal funding has not permitted the establishment of a robust wildlifeprogram. In addition, wildlifeconservation has been furtherimpacted by a failureto establish landowner incentives, power struggles over user rights, resistance to change, and lack of trust and experience in protecting and managing Mexico's wildlife. We believe future strategies for wildlifeprograms must take into account Mexico's highly diversifiedmosaic of ecosystems, cultures, socioeconomic levels, and land tenure and political systems. -

Association of Midwest Fish & Game Law

ASSOCIATION OF MIDWEST FISH & GAME LAW ENFORCEMENT OFFICERS EST. 1944 ANNUAL AGENCY REPORTS 2019 ASSOCIATION OF MIDWEST FISH & GAME LAW ENFORCEMENT OFFICERS ALBERTA COLORADO INDIANA IOWA MICHIGAN MINNESOTA MISSOURI NORTH DAKOTA OHIO OKLAHOMA SASKATCHEWAN SOUTH DAKOTA TEXAS WISCONSIN Association of Midwest Fish and Game Law Enforcement Officers 2020 Agency Report State/Province: Alberta Fish and Wildlife Enforcement Branch Submitted by: Supt. Miles Grove Date: May 15, 2020 based on a ‘closest car’ policy. Once the Training Issues emergency is handled and the police are able to Describe any new or innovative training programs or assume total control, fish and wildlife officers will techniques which have been recently developed, revert to core mandated conservation enforcement implemented or are now required. duties. Unique Cross Boundary or Cooperative, The branch has postponed mandatory re- Enforcement Efforts certifications and in-service training due to COVID-19 restrictions. In Alberta, we now have the go ahead to Describe any Interagency, interstate, international, resume some training with strict protocols in state/tribal, or other cross jurisdictional enforcement accordance to Alberta Health Services. The Western efforts (e.g. major Lacey Act investigations, progress Conservation Law Enforcement Academy is with Wildlife Violator Compacts, improvements in postponed until September 2020 and may be interagency communication (WCIS), etc.) differed to May 2021 based on the lack of recruitment in western Canada. The Government of Special Investigations Section – Major Investigations Alberta has announced that fish and wildlife officers and Intelligence Unit (MIIU) will be assisting the RCMP (Provincial Police) with response to priority one and two emergencies in rural The Special Investigations Section is the designated areas. -

Hasbro Launches KRE-O Cityville® Invasion, Innovative Construction Line Featuring New Sonic Motion Technology

August 1, 2013 Hasbro Launches KRE-O Cityville® Invasion, Innovative Construction Line Featuring New Sonic Motion Technology Kids will be Wowed by Zany New Characters, Movement and KRE-O CITYVILLE INVASION App from ZYNGA® Pawtucket, R.I. – August 1, 2013 – Dr. Mayhem’s henchmen are invading and it’s up to builders nationwide to keep their city creations safe! Hasbro, Inc. (NASDAQ: HAS), in collaboration with Zynga® (NASDAQ: ZNGA), expands its popular KRE-O construction line with the introduction of the KRE-O CITYVILLE® INVASION collection, brick-based sets which turn ordinary cityscapes into madcap environments where builders’ imaginations can run as wild as Dr. Mayhem. In addition to mischievous new KREON figures including zombies, gorillas, and vampires, several of the KRE-O CITYVILLE INVASION sets include playful sounds and SONIC MOTION TECHNOLOGY, a unique new innovation to the construction category. In each KRE-O CITYVILLE INVASION building set equipped with SONIC MOTION TECHNOLOGY, sound waves trigger specific movements in special KRE-O bricks creating a fun action scene filled with KREON figures spinning, shuffling, and swimming into action! Fans can watch as the helicopter included in the SKYSCRAPER MAYHEM set spins to life or AMY APEKEEPER chases after ZAPE the gorilla before he demolishes the city. “The introduction of KRE-O CITYVILLE INVASION brings a wonderful diversity and playfulness to the construction aisle with its quirky backstory and technological advancements,’ said Kim Boyd, Senior Director Global Brand Marketing, Hasbro, Inc. ‘Together with Zynga, we’re thrilled to give building fans a whole new way to play, both online with the immersive CITYVILLE INVASION app and in physical form as SONIC MOTION TECHNOLOGY makes KRE-O brick-based creations come to life.” The building fun continues digitally with the free ZYNGA KRE-O CITYVILLE INVASION app, developed with kids in mind and available now on the Apple Store or Google Play.