Natural Defense Mansavage.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Laws of Pennsylvania

278 LAWS OF PENNSYLVANIA, appraisal given, in writing, by three (3) or more persons competent to give appraisal by reason of being a manufac- turer, dealer or user of such furniture or equipment. In no instance shall the school district pay more than the average of such appraised values. Necessary costs of securing such appraised values may be paid by the school district. Provided when appraised value is deter- mined to be more than one thousand dollars ($1,000), purchase may be made only after public notice has been given by advertisement once a week for three (3) weeks in not less than two (2) newspapers of general circula- tion. In any district where no newspaper is published, said notice may, in lieu of such publication, be posted in at least five (5) public places. Such advertisement shall specify the items to be purchased, name the vendor, state the proposed purchase price, and state the time and place of the public meeting at which such proposed purchase shall be considered by the board of school directors. APPROVED—The 8th day of June, A. D. 1961. DAVID L. LAWRENCE No. 163 AN ACT Amending the act of June 3, 1937 (P. L. 1225), entitled “An act concerning game and other wild birds and wild animals; and amending, revising, consolidating, and changing the law relating thereto,” removing provisions relating to archery preserves. The Game Law. The General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Penn- sylvania hereby enacts as follows: Section 317, act of June 3, 1937, Section 1. Section 317, act of June 3, 1937 (P. -

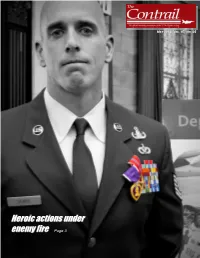

Heroic Actions Under Enemy Fire Page 3

MAY 2013, VOL. 47, NO. 05 HeroicHeroic actionsactions underunder enemyenemy firefire Page 3 PILOTPILOT FORFOR AA DAY!DAY! AY OL O M 2013, V . 47, N . 05 FEATURES: Pg. 3: Heroic Actions Pg. 5: NDI life under lights Pg. 6: Pilot for a Day! Pg. 7: Spirit of A.C. part 3 And more... COVER: Sears, an explosive ordnance disposal technician with the 177th Fighter Wing, defused two improvised explo- sive devices and made five trips across open terrain un- der heavy enemy fire to aid a wounded coalition soldier and to engage insurgent forces. Photo by Master Sgt. Mark Olsen SOCIAL MEDIA Find us on the web! www.177thFW.ang.af.mil Facebook.com/177FW Twitter.com/177FW Youtube.com/177thfighterwing This funded newspaper is an authorized monthly 177TH FW EDITORIAL STAFF publication for members of the U.S. Military Services. Col. Kerry M. Gentry, Commander Contents of the Contrail are not necessarily the official 1st Lt. Amanda Batiz, Public Affairs Officer Master Sgt. Andrew Moseley, Public Affairs/Visual Information Manager view of, or endorsed by, the 177th FW, the U.S. Gov- Master Sgt. Shawn Mildren:, Photographer ernment, the Department of Defense or the Depart- Tech. Sgt. Andrew Merlock Jr., Photographer Tech. Sgt. Matt Hecht: Editor, Layout, Photographer, Writer ment of the Air Force. The editorial content is edited, prepared, and provided by the Public Affairs Office of 177FW/PA the 177th Fighter Wing. All photographs are Air Force 400 Langley Road, Egg Harbor Township, NJ 08234-9500 (609) 761-6259; (609) 677-6741 (FAX) photographs unless otherwise indicated. -

U.S. President's Committee for Hungarian Refugee Relief

DWIGHT D. EISENHOWER LIBRARY ABILENE, KANSAS U.S. PRESIDENT’S COMMITTEE FOR HUNGARIAN REFUGEE RELIEF: Records, 1957 A67-4 Compiled by Roland W. Doty, Jr. William G. Lewis Robert J. Smith 16 cubic feet 1956-1957 September 1967 INTRODUCTION The President’s Committee for Hungarian Refugee Relief was established by the President on December 12, 1956. The need for such a committee came about as a result of the United States’ desire to take care of its fair share of the Hungarians who fled their country beginning in October 1956. The Committee operated until May, 1957. During this time, it helped re-settle in the United States approximately 30,000 refugees. The Committee’s small staff was funded from the Special Projects Group appropriation. In its creation, the Committee was assigned the following duties and objectives: a. To assist in every way possible the various religious and other voluntary agencies engaged in work for Hungarian Refugees. b. To coordinate the efforts of these agencies, with special emphasis on those activities related to resettlement of the refugees. The Committee also served as a focal point to which offers of homes and jobs could be forwarded. c. To coordinate the efforts of the voluntary agencies with the work of the interested governmental departments. d. It was not the responsibility of the Committee to raise money. The records of the President’s Committee consists of incoming and outgoing correspondence, press releases, speeches, printed materials, memoranda, telegrams, programs, itineraries, statistical materials, air and sea boarding manifests, and progress reports. The subject areas of these documents deal primarily with requests from the public to assist the refugees and the Committee by volunteering homes, employment, adoption of orphans, and even marriage. -

Department of Fish and Game Celebrates 130 Years of Serving

DepartmentDepartment ofof FishFish andand GameGame celebratescelebrates 130130 yyearearss ofof servingserving CalifCaliforniaornia .. .. .. n 1970, the Department of Fish and Game state hatching house is established at the turned 100 years old. At that time, a history University of California in Berkeley. ofI significant events over that 100 years was published. A frequently requested item, the 1871. First importation of fish-1,500 young history was updated in 1980, and now we have shad. Two full-time deputies (wardens) are another 20 years to add. We look forward to appointed, one to patrol San Francisco Bay seeing where fish and wildlife activities lead us and the other the Lake Tahoe area. in the next millennium. Editor 1872. The Legislature passes an act enabling 1849. California Territorial Legislature the commission to require fishways or in- adopts common law of England as the rule lieu hatcheries where dams or other in all state courts. Before this, Spanish and obstacles impede or prevent fish passage. then Mexican laws applied. Most significant legal incident was the Mexican 1878. The authority of the Fish government decree in 1830 that California Commission is expanded to include game mountain men were illegally hunting and as well as fish. fishing. Captain John Sutter, among others, had been responsible for enforcing 1879. Striped bass are introduced from New Mexican fish and game laws. Jersey and planted at Carquinez Strait. 1851. State of California enacts first law 1883. Commissioners establish a Bureau of specifically dealing with fish and game Patrol and Law Enforcement. Jack London matters. This concerned the right to take switches sides from oyster pirate to oysters and the protection of property Commission deputy. -

Piping Plover Comprehensive Conservation Strategy

Cover graphic: Judy Fieth Cover photos: Foraging piping plover - Sidney Maddock Piping plover in flight - Melissa Bimbi, USFWS Roosting piping plover - Patrick Leary Sign - Melissa Bimbi, USFWS Comprehensive Conservation Strategy for the Piping Plover in its Coastal Migration and Wintering Range in the Continental United States INTER-REGIONAL PIPING PLOVER TEAM U.S. FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE Melissa Bimbi U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 4, Charleston, South Carolina Robyn Cobb U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 2, Corpus Christi, Texas Patty Kelly U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 4, Panama City, Florida Carol Aron U.S. Fish and Wildlife Region 6, Bismarck, North Dakota Jack Dingledine/Vince Cavalieri U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 3, East Lansing, Michigan Anne Hecht U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 5, Sudbury, Massachusetts Prepared by Terwilliger Consulting, Inc. Karen Terwilliger, Harmony Jump, Tracy M. Rice, Stephanie Egger Amy V. Mallette, David Bearinger, Robert K. Rose, and Haydon Rochester, Jr. Comprehensive Conservation Strategy for the Piping Plover in its Coastal Migration and Wintering Range in the Continental United States Comprehensive Conservation Strategy for the Piping Plover in its Coastal Migration and Wintering Range in the Continental United States PURPOSE AND GEOGRAPHIC SCOPE OF THIS STRATEGY This Comprehensive Conservation Strategy (CCS) synthesizes conservation needs across the shared coastal migration and wintering ranges of the federally listed Great Lakes (endangered), Atlantic Coast (threatened), and Northern Great Plains (threatened) piping plover (Charadrius melodus) populations. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s 2009 5-Year Review recommended development of the CCS to enhance collaboration among recovery partners and address widespread habitat loss and degradation, increasing human disturbance, and other threats in the piping plover’s coastal migration and wintering range. -

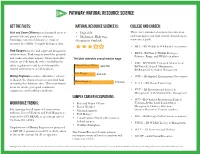

Natural Resource Science

Pathway: Natural Resource Science Get the Facts: Natural Resource Science is: College and Career: Fish and Game Officers patrol assigned areas to • High skill There are a number of options for education prevent fish and game law violations. • Medium to High wage and training beyond high school, depending on Investigate reports of damage to crops or Occupation Outlook: your career goals. property by wildlife. Compile biological data. • BYU – BS Wildlife & Wildlands Conservation Park Rangers protect and supervise designated outdoor areas. Park rangers patrol the grounds • BYUI – BS Plant & Wildlife Ecology— Fisheries, Range, and Wildlife emphases and make sure that campers, hikers and other The Utah statewide annual median wage: visitors are following the rules-- including fire • USU – BS Wildlife Ecology & Management; safety regulations-- and do not disrupt the Fish and Game Officer $49,760 BS Forest Ecology & Management; natural environment or fellow guests. BS Rangeland Ecology & Management Park Ranger $44,600 Mining Engineers conduct sub-surface surveys • WSU – BS Applied Environmenta Geosciences to identify the characteristics of potential land Mining Engineer or mining development sites. They may inspect $78,860 • U of U – BS Mining Engineering areas for unsafe geological conditions, equipment, and working conditions. • UVU – BS Environmental Science & Management; AAS Wildland Fire Management Sample Career Occupations: • SUU – BS Outdoor Recreation in Parks & Workforce Trends: • Fish and Game Officer Tourism—Public Lands Leadership & • Forest Worker Management, Outdoor Education, Job openings for all types of Conservation • Mining Engineer Outdoor Recreation Tourism emphases Officers, Forest Workers and Park Rangers is • Park Ranger • DSU – BS Biology—Natural Sciences emphasis expected to INCREASE at an average rate of • Conservation Officer with a state or 7% from 2014-2024. -

Historical Dictionary of Air Intelligence

Historical Dictionaries of Intelligence and Counterintelligence Jon Woronoff, Series Editor 1. British Intelligence, by Nigel West, 2005. 2. United States Intelligence, by Michael A. Turner, 2006. 3. Israeli Intelligence, by Ephraim Kahana, 2006. 4. International Intelligence, by Nigel West, 2006. 5. Russian and Soviet Intelligence, by Robert W. Pringle, 2006. 6. Cold War Counterintelligence, by Nigel West, 2007. 7. World War II Intelligence, by Nigel West, 2008. 8. Sexspionage, by Nigel West, 2009. 9. Air Intelligence, by Glenmore S. Trenear-Harvey, 2009. Historical Dictionary of Air Intelligence Glenmore S. Trenear-Harvey Historical Dictionaries of Intelligence and Counterintelligence, No. 9 The Scarecrow Press, Inc. Lanham, Maryland • Toronto • Plymouth, UK 2009 SCARECROW PRESS, INC. Published in the United States of America by Scarecrow Press, Inc. A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 www.scarecrowpress.com Estover Road Plymouth PL6 7PY United Kingdom Copyright © 2009 by Glenmore S. Trenear-Harvey All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Trenear-Harvey, Glenmore S., 1940– Historical dictionary of air intelligence / Glenmore S. Trenear-Harvey. p. cm. — (Historical dictionaries of intelligence and counterintelligence ; no. 9) Includes bibliographical references. ISBN-13: 978-0-8108-5982-1 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8108-5982-3 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-0-8108-6294-4 (eBook) ISBN-10: 0-8108-6294-8 (eBook) 1. -

Florida Gulf Environmental Benefit Fund Restoration Strategy Funded by the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation – Gulf Environmental Benefit Fund

Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission and Florida Department of Environmental Protection Florida Gulf Environmental Benefit Fund Restoration Strategy Funded by the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation – Gulf Environmental Benefit Fund Prepared with assistance from Abt Associates January 2018 Table of Contents List of Tables ............................................................................................................................ V Glossary of Terms and Acronyms ......................................................................................VI Executive Summary .............................................................................................................VII 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 National Fish and Wildlife Foundation—Gulf Environmental Benefit Fund Background .......................1 1.1.1 GEBF Funding Priorities ...............................................................................................................................1 1.2 Restoration Strategy ..................................................................................................................................................2 1.2.1 Geography ........................................................................................................................................................3 1.2.2 Watershed Approach .....................................................................................................................................3 -

The North American F-86 Sabre, a Truly Iconic American Aircraft Part 3 – the F-86E and the All Flying Tail

On the cover: Senior Airman David Ringer, left, uses a ratchet strap to pull part of a fence in place so Senior Airman Michael Garcia, center, and 1st Lt. Andrew Matejek can secure it in place on May 21, 2015 at Coast Guard Air Station Clearwater. The fence was replaced after the old rusted fence was removed and the drainage ditch was dug out. (ANG/Airman 1st Class Amber Powell) JUNE 2015, VOL. 49 NO. 6 THE CONTRAIL STAFF 177TH FW COMMANDER COL . JOHN R. DiDONNA CHIEF, PUBLIC AFFAIRS CAPT. AMANDA BATIZ PUBLIC AFFAIRS SUPERINTENDENT MASTER SGT. ANDREW J. MOSELEY PHOTOJOURNALIST TECH. SGT. ANDREW J. MERLOCK EDITOR/PHOTOJOURNALIST SENIOR AIRMAN SHANE S. KARP EDITOR/PHOTOJOURNALIST AIRMAN 1st CLASS AMBER POWELL AVIATION HISTORIAN DR. RICHARD PORCELLI WWW.177FW.ANG.AF.MIL This funded newspaper is an authorized monthly publication for members of the U.S. Military Services. Contents of The Contrail are not necessarily the official view of, or endorsed by, the 177th Fighter Wing, the U.S. Government, the Department of Defense or the Depart- On desktop computers, click For back issues of The Contrail, ment of the Air Force. The editorial content is edited, prepared, and provided by the Public Affairs Office of the 177th Fighter Wing. All Ctrl+L for full screen. On mobile, and other multimedia products photographs are Air Force photographs unless otherwise indicated. tablet, or touch screen device, from the 177th Fighter Wing, tap or swipe to flip the page. please visit us at DVIDS! Maintenance 101 Story by Lt. Col. John Cosgrove, 177th Fighter Wing Maintenance Group Commander When you attend a summer barbecue Storage Area, Avionics Intermediate equipment daily; in all types of and someone finds out you’re in the Shop/Electronic Counter-measures and weather but they really get to show off military, have they ever asked, “Do you Fabrication. -

Historical Highlights Related to the Illinois Department of Natural Resources and Conservation in Illinois

Historical Highlights Related to the Illinois Department of Natural Resources and Conservation in Illinois 1492 - The first Europeans come to North America. 1600 - The land that is to become Illinois encompasses 21 million acres of prairie and 14 million acres of forest. 1680 - Fort Crevecoeur is constructed by René-Robert-Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle and his men on the bluffs above the Illinois River near Peoria. A few months later, the fort is destroyed. You can read more about the fort at http://www.ftcrevecoeur.org/history.html. 1682 - René-Robert-Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, and Henri de Tonti reach the mouth of the Mississippi River. Later, they build Fort St. Louis atop Starved Rock along the Illinois River. http://www.museum.state.il.us/muslink/nat_amer/post/htmls/arch_starv.html http://more.pjstar.com/peoria-history/ 1699 - A Catholic mission is established at Cahokia. 1703 - Kaskaskia is established by the French in southwestern Illinois. The site was originally host to many Native American villages. Kaskaskia became an important regional center. The Illinois Country, including Kaskaskia, came under British control in 1765, after the French and Indian War. Kaskaskia was taken from the British by the Virginia militia in the Revolutionary War. In 1818, Kaskaskia was named the first capital of the new state of Illinois. http://www.museum.state.il.us/muslink/nat_amer/post/htmls/arch_starv.html http://www.illinoisinfocus.com/kaskaskia.html 1717 - The original French settlements in Illinois are placed under the government of Louisiana. 1723 - Prairie du Rocher is settled. http://www.illinoisinfocus.com/prairie-du-rocher.html 1723 - Fort de Chartres is constructed. -

Okaloosa County 136 S

OKALOOSA COUNTY 136 S. Bronough Street 800 N. Magnolia Avenue, Suite 1100 1580 Waldo Palmer Lane, Suite 1 A message from Governor Tallahassee, Florida 32301 Orlando, Florida 32803 Tallahassee, Florida 32308 Scott on the future of (407) 956-5600 (850) 921-1119 Florida’s Freight and Trade FREIGHT & LOGISTICS OVERVIEW FLORIDA DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION FDOT CONTACTS Ananth Prasad, P.E. Richard Biter Secretary of Transportation Assistant Secretary for Intermodal Phone (850) 414-5205 Systems Development [email protected] Phone (850) 414-5235 [email protected] Juan Flores Tommy Barfield Administrator, Freight Logistics & District 3, Secretary Passenger Operations Phone (850) 415-9200 Phone (850) 414-5245 [email protected] [email protected] Federal Legislative Contacts United States Senate Bill Nelson Phone (202) 224-5274 United States Senate Marco Rubio Phone (202) 224-3071 US House of Representatives District 1, Jeff Miller Phone (202) 225-4136 State Legislative Contacts: Florida Senate District 1, Greg Evers Phone (850) 487-5001 Florida Senate District 2, Don Gaetz Phone (850) 487-5002 Florida House of Representatives FDOT MISSION: District 3, Doug Broxson Phone (850) 717-5003 THE DEPARTMENT WILL PROVIDE A SAFE TRANSPORTATION SYSTEM THAT ENSURES THE MOBILITY OF PEOPLE AND GOODS, ENHANCES ECONOMIC PROSPERITY AND Florida House of Representatives District 4, Matt Gaetz PRESERVES THE QUALITY OF OUR ENVIRONMENT AND COMMUNITIES. Phone (850) 717-5004 In recognition of the significant role that freight HB599 requires FDOT to lead the development of mobility plays as an economic driver for the state, a plan to “enhance the integration and connectivity an Office of Freight, Logistics and Passenger of the transportation system across and between Operations has been created at FDOT. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 110 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 110 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 153 WASHINGTON, MONDAY, SEPTEMBER 24, 2007 No. 142 House of Representatives The House met at 12:30 p.m. and was tion, and that’s despite fits and starts now seen is a health care clinic in called to order by the Speaker pro tem- with government health and so forth. Johnson Bayou, where the community pore (Ms. HIRONO). It’s the individuals, local officials, fam- came together to put this in place to f ilies on the ground that made the dif- create access for health care. ference. You know, we all talk about how all DESIGNATION OF SPEAKER PRO This storm also caused unprece- politics is local, but I would submit TEMPORE dented damage to the oil and gas indus- that all health care is local. If we don’t The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- try. Again, individuals working in have access to health care, it doesn’t fore the House the following commu- those companies got our oil and gas in- matter. It doesn’t matter what’s avail- nication from the Speaker: frastructure back up and running in able in Boston, Massachusetts, or in record time, so that we could fuel San Francisco and New York, because WASHINGTON, DC, if the folks down in Johnson Bayou September 24, 2007. America’s energy needs. I hereby appoint the Honorable MAZIE K. At the Federal level, funds have been don’t have access to health care, then HIRONO to act as Speaker pro tempore on appropriated for assistance, but they what good is it? What good is the great this day.