Targeting Voters on Television

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Politics and Policies

Politics and Policies Rowland-Hite Health Planning Seminar May 6, 2011 2012 Presidential • Obama polls improving – 50% threshold – Tax deal in December – Move to the center – Unhappy base, but no challenger • Republicans – No clear front runner (historic) – Late starting – Significant divisions Political leverage…Senate • What‟s at stake? – 33 seats 23 Democrats 10 Republicans • Democratic vulnerabilities – States where John McCain won in 2008 Joe Manchin (D-WV)…+13 Claire McCaskill (D-MO)…+0.1 Ben Nelson (D-NE)…+14.9 John Tester (D-MT)…+2.3 – States where GOP flipped Senate seats this year Sherrod Brown (D-OH)…Rob Portman (R) Bob Casey (D-PA)…Pat Toomey (R) [Kent Conrad (D-ND)]…Jon Hoeven (R) Herb Kohl (D-WI)…Ron Johnson (R) Political leverage…House 31 new GOP (of 62) representatives who represent districts won by President Obama • FLORIDA • NEW HAMPSHIRE • TEXAS – Daniel Webster – Charlie Bass – Francisco Canseco – Allen West – Frank Guinta – Blake Farenthold • ILLINOIS • NEW JERSEY • VIRGINIA – Robert Dold – Jon Runyan – Scott Rigell – Adam Kinzinger • NEW YORK • WASHINGTON – Randy Hultgren – Ann Marie Buerkle – Jamie Herrera – Bobby Schilling – Chris Gibson • WISCONSIN – Joe Walsh – Richard Hanna – Sean Duffy • KANSAS – Nan Hayworth – Reid Ribble – Kevin Yoder • NORTH CAROLINA • MICHIGAN – Renee Elmers – Dan Benishek • OHIO – Tim Walberg – Steve Chabot • MINNESOTA – Steve Stivers – Chip Cravaack • PENNSYLVANIA • NEVADA – Lou Barletta – Joe Heck – Mike Fitzpatrick – Pat Meehan Multiple opportunities for reducing spending Legislative Platforms • Continuing resolution(s) on appropriations • Debt limit extension(s) • Congressional Budget Resolutions Congressional Budget Resolution • Not a law…does NOT require Presidential signature • Congressional work-plan… guides committees with Rep. Ryan Sen. -

114TH CONGRESS / First Session Available at Frcaction.Org/Scorecard

FRC ACTION VOTE SCORECARD 114TH CONGRESS / First Session Available at FRCAction.org/scorecard U.S. House of Representatives and U.S. Senate Dear Voter and Friend of the Family, FRC Action presents our Vote Scorecard for the First Session of the 114th Congress. This online Scorecard contains a compilation of significant votes on federal legislation affecting faith, family, and freedom that FRC Action either supported or opposed. These recorded votes span the 2015 calendar year and include the greatest number of pro-life votes in history, after the U.S. House increased its Republican membership and the U.S. Senate was returned to Republican control. The year began with a bipartisan effort in the House to prohibit federal funds from being used to pay for abortion coverage under Obamacare. Congress successfully fought to restrict FDA approval of some forms of embryo-destructive research. The House, once again, passed legislation that would prevent late abortions on 5 month old pain-capable unborn children, and although the Senate was unable to pass the bill due to the 60 vote threshold, for the first time, a majority of Senators voted in favor of the bill. The public release of videos revealing Planned Parenthood’s organ harvesting practices renewed efforts to defund this scandal-ridden organization and redirect funding towards community health centers. In an unprecedented victory, the House and Senate passed a budget reconciliation bill, the Restoring Ameri- cans’ Healthcare Freedom Reconciliation Act, which would have eliminated a significant portion of Planned Parenthood’s funding—roughly 80%— and repealed key provisions of Obamacare. -

167 Representatives on FY 07 Animal Welfare Funding Letter

167 Representatives on FY 07 Animal Welfare Funding Letter Arizona Hawaii Missouri Pennsylvania Rep. Raul Grijalva (D) Rep. Ed Case (D) Rep. Russ Carnahan (D) Rep. Robert Brady (D) Rep. Ed Pastor (D) Rep. William Lacy Clay (D) Rep. Mike Doyle (D) Rep. Emanuel Cleaver (D) Rep. Phil English (R) Illinois Rep. Chaka Fattah (D) Arkansas Rep. Judy Biggert (R) Rep. Vic Snyder (D) Rep. Jerry Costello (D) Nevada Rep. Mike Fitzpatrick (R) Rep. Danny Davis (D) Rep. Shelley Berkley (D) Rep. Jim Gerlach (R) Rep. Rahm Emanuel (D) Rep. Todd Platts (R) California Rep. Lane Evans (D) Rep. Allyson Schwartz (D) Rep. Howard Berman (D) New Hampshire Rep. Curt Weldon (R) Rep. Mary Bono (R) Rep. Luis Gutierrez (D) Rep. Charles Bass (R) Rep. Lois Capps (D) Rep. Dan Lipinski (D) Rep. Bobby Rush (D) Rhode Island Rep. Susan Davis (D) New Jersey Rep. Anna Eshoo (D) Rep. Janice Schakowsky (D) Rep. Patrick Kennedy (D) Rep. John Shimkus (R) Rep. Robert Andrews (D) Rep. James Langevin (D) Rep. Sam Farr (D)* Rep. Jerry Weller (R) Rep. Mike Ferguson (R) Rep. Bob Filner (D) Rep. Rush Holt (D) Rep. Elton Gallegly (R) Rep. Frank LoBiondo (R) South Carolina Rep. Michael Honda (D) Indiana Rep. Frank Pallone, Jr. (D) Rep. James Clyburn (D) Rep. Tom Lantos (D) Rep. Dan Burton (R) Rep. Bill Pascrell, Jr. (D) Rep. John Spratt (D) Rep. Barbara Lee (D) Rep. Julia Carson (D) Rep. Joe Wilson (R) Rep. Donald Payne (D) Rep. Zoe Lofgren (D) Rep. Jim Saxton (R) Rep. Doris Matsui (D) Iowa Rep. Christopher Smith (R) South Dakota Rep. -

19738 Hon. Grace F. Napolitano Hon. Curt Weldon Hon

19738 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS October 12, 2001 TRIBUTE TO ANNA MARIA ARIAS why she was choosing to undergo the com- three were called by destiny to perform heroic plicated bone marrow surgery, Anna Maria feats. As fire raged through the Pentagon, Mr. HON. GRACE F. NAPOLITANO simply said, ‘‘I have to do this, we have impor- Jones, Staff Sgt. Braman, and Major Pantaleo OF CALIFORNIA tant work to do and this thing keeps getting in rushed inside. These three men along with all IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES the way.’’ That was Anna Maria, totally de- the public safety and military personnel at the voted to her work and committed to serving scene were responsible for rescuing hundreds Friday, October 12, 2001 others. of men and women injured by the explosion, Mrs. NAPOLITANO. Mr. Speaker, I rise Last Sunday, I attended Anna Maria Arias’ the building collapse and burning jet fuel dur- today with a heavy heart to honor the memory memorial mass at the Church of Guadalupe ing the first minutes following the attack. After of an exceptional woman, Anna Maria Arias. and her burial ceremony at Mt. View Ceme- the injured had been saved, they remained on On Monday, October 1, 2001, Anna Maria lost tery, in San Bernardino, CA. Her husband the site for many days to recover the bodies a seven-year battle against aplastic anemia Robert Bard and her mother Rita Valenzuela of those who perished. and passed away from complications related spoke of the tremendous courage and deter- I salute all Americans who answered the to a bone marrow transplant procedure at MD mination of one so young. -

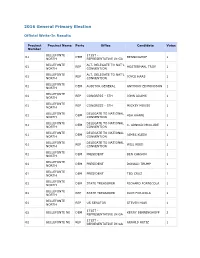

2016 General Primary Write-Ins

2016 General Primary Election Official Write-In Results Precinct Precinct Name Party Office Candidate Votes Number BELLEFONTE 171ST - 01 DEM BENNINGHOF 1 NORTH REPRESENTATIVE IN GA BELLEFONTE ALT. DELEGATE TO NAT'L 01 REP HOSTERMAN, TROY 1 NORTH CONVENTION BELLEFONTE ALT. DELEGATE TO NAT'L 01 REP JOYCE HAAS 1 NORTH CONVENTION BELLEFONTE 01 DEM AUDITOR GENERAL ANTHONY EDMONDSON 1 NORTH BELLEFONTE 01 REP CONGRESS - 5TH JOHN ADAMS 1 NORTH BELLEFONTE 01 REP CONGRESS - 5TH MICKEY MOUSE 1 NORTH BELLEFONTE DELEGATE TO NATIONAL 01 DEM ASH KHARE 1 NORTH CONVENTION BELLEFONTE DELEGATE TO NATIONAL 01 DEM C. ARNOLD MCCLURE 1 NORTH CONVENTION BELLEFONTE DELEGATE TO NATIONAL 01 DEM JAMES KLEIN 1 NORTH CONVENTION BELLEFONTE DELEGATE TO NATIONAL 01 REP WILL REED 1 NORTH CONVENTION BELLEFONTE 01 DEM PRESIDENT BEN CARSON 1 NORTH BELLEFONTE 01 DEM PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP 1 NORTH BELLEFONTE 01 DEM PRESIDENT TED CRUZ 1 NORTH BELLEFONTE 01 DEM STATE TREASURER RICHARD FORNICOLA 1 NORTH BELLEFONTE 01 REP STATE TREASURER RICH FORICOLA 1 NORTH BELLEFONTE 01 REP US SENATOR STEVEN HAIR 1 NORTH 171ST - 02 BELLEFONTE NE DEM KERRY BENNINGHOFF 2 REPRESENTATIVE IN GA 171ST - 02 BELLEFONTE NE REP GERALD RETIZ 1 REPRESENTATIVE IN GA ALT. DELEGATE TO NAT'L 02 BELLEFONTE NE REP BARRY CASPER 1 CONVENTION ALT. DELEGATE TO NAT'L 02 BELLEFONTE NE REP DREW CURTIN 1 CONVENTION ALT. DELEGATE TO NAT'L 02 BELLEFONTE NE REP GERALD RETIZ 1 CONVENTION ALT. DELEGATE TO NAT'L 02 BELLEFONTE NE REP JAMES KLENE 1 CONVENTION ALT. DELEGATE TO NAT'L 02 BELLEFONTE NE REP JIM WORTHINGTON 1 CONVENTION ALT. -

To Download This Handout As an Adobe Acrobat

AEI Election Watch 2006 October 11, 2006 Bush’s Ratings Congress’s Ratings Approve Disapprove Approve Disapprove CNN/ORC Oct. 6-8 39 56 CNN/ORC Oct. 6-8 28 63 Gallup/USAT Oct. 6-8 37 59 Gallup/USAT Oct. 6-8 24 68 ABC/WP Oct. 5-8 39 60 ABC/WP Oct. 5-8 32 66 CBS/NYT Oct. 5-8 34 60 CBS/NYT Oct. 5-8 27 64 Newsweek Oct. 5-6 33 59 Time/SRBI Oct. 3-4 31 57 Time/SRBI Oct. 3-4 36 57 AP/Ipsos Oct. 2-4 27 69 AP/Ipsos Oct. 2-4 38 59 Diag.-Hotline Sep. 24-26 28 65 PSRA/Pew Sep. 21-Oct. 4 37 53 LAT/Bloom Sep. 16-19 30 57 NBC/WSJ Sep. 30-Oct. 2 39 56 Fox/OD Sep. 12-13 29 53 Fox/OD Sep. 26-27 42 54 NBC/WSJ (RV) Sep. 8-11 20 65 Diag-Hotline Sep. 24-26 42 56 LAT/Bloom Sep. 16-19 45 52 Final October approval rating for the president and Final October approval rating for Congress and number of House seats won/lost by the president’s number of House seats won/lost by the president’s party party Gallup/CNN/USA Today Gallup/CNN/USA Today Number Number Approve of seats Approve of seats Oct. 2002 67 +8 Oct. 2002 50 +8 Oct. 1998 65 +5 Oct. 1998 44 +5 Oct. 1994 48 -52 Oct. 1994 23 -52 Oct. 1990 48 -9 Oct. 1990 24 -9 Oct. 1986 62 -5 Apr. -

115Th Congress Roster.Xlsx

State-District 114th Congress 115th Congress 114th Congress Alabama R D AL-01 Bradley Byrne (R) Bradley Byrne (R) 248 187 AL-02 Martha Roby (R) Martha Roby (R) AL-03 Mike Rogers (R) Mike Rogers (R) 115th Congress AL-04 Robert Aderholt (R) Robert Aderholt (R) R D AL-05 Mo Brooks (R) Mo Brooks (R) 239 192 AL-06 Gary Palmer (R) Gary Palmer (R) AL-07 Terri Sewell (D) Terri Sewell (D) Alaska At-Large Don Young (R) Don Young (R) Arizona AZ-01 Ann Kirkpatrick (D) Tom O'Halleran (D) AZ-02 Martha McSally (R) Martha McSally (R) AZ-03 Raúl Grijalva (D) Raúl Grijalva (D) AZ-04 Paul Gosar (R) Paul Gosar (R) AZ-05 Matt Salmon (R) Matt Salmon (R) AZ-06 David Schweikert (R) David Schweikert (R) AZ-07 Ruben Gallego (D) Ruben Gallego (D) AZ-08 Trent Franks (R) Trent Franks (R) AZ-09 Kyrsten Sinema (D) Kyrsten Sinema (D) Arkansas AR-01 Rick Crawford (R) Rick Crawford (R) AR-02 French Hill (R) French Hill (R) AR-03 Steve Womack (R) Steve Womack (R) AR-04 Bruce Westerman (R) Bruce Westerman (R) California CA-01 Doug LaMalfa (R) Doug LaMalfa (R) CA-02 Jared Huffman (D) Jared Huffman (D) CA-03 John Garamendi (D) John Garamendi (D) CA-04 Tom McClintock (R) Tom McClintock (R) CA-05 Mike Thompson (D) Mike Thompson (D) CA-06 Doris Matsui (D) Doris Matsui (D) CA-07 Ami Bera (D) Ami Bera (D) (undecided) CA-08 Paul Cook (R) Paul Cook (R) CA-09 Jerry McNerney (D) Jerry McNerney (D) CA-10 Jeff Denham (R) Jeff Denham (R) CA-11 Mark DeSaulnier (D) Mark DeSaulnier (D) CA-12 Nancy Pelosi (D) Nancy Pelosi (D) CA-13 Barbara Lee (D) Barbara Lee (D) CA-14 Jackie Speier (D) Jackie -

Vital Statistics on Congress 2001-2002

Vital Statistics on Congress 2001-2002 Vital Statistics on Congress 2001-2002 NormanJ. Ornstein American Enterprise Institute Thomas E. Mann Brookings Institution Michael J. Malbin State University of New York at Albany The AEI Press Publisher for the American Enterprise Institute WASHINGTON, D.C. 2002 Distributed to the Trade by National Book Network, 152.00 NBN Way, Blue Ridge Summit, PA 172.14. To order call toll free 1-800-462.-642.0 or 1-717-794-3800. For all other inquiries please contact the AEI Press, 1150 Seventeenth Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. 2.0036 or call 1-800-862.-5801. Available in the United States from the AEI Press, do Publisher Resources Inc., 1224 Heil Quaker Blvd., P O. Box 7001, La Vergne, TN 37086-7001. To order, call toll free: 1-800-937-5557. Distributed outside the United States by arrangement with Eurospan, 3 Henrietta Street, London WC2E 8LU, England. ISBN 0-8447-4167-1 (cloth: alk. paper) ISBN 0-8447-4168-X (pbk.: alk. paper) 13579108642 © 2002 by the American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research, Washington, D.C. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without permission in writing from the American Enterprise Institute except in the case of brief quotations embodied in news articles, critical articles, or reviews. The views expressed in the publications of the American Enterprise Institute are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the staff, advisory panels, officers, or trustees of AEI. Printed in the United States ofAmerica Contents List of Figures and Tables vii Preface ............................................ -

105Th Congress 245

PENNSYLVANIA 105th Congress 245 PENNSYLVANIA (Population 1995, 12,072,000) SENATORS ARLEN SPECTER, Republican, of Philadelphia, PA; born in Wichita, KS, February 12, 1930; graduated, Russell High School, Russell, KS, 1947; University of Pennsylvania, 1951, B.A., international relations, Phi Beta Kappa; Yale Law School, LL.B., 1956; board of editors, Law Journal; served in U.S. Air Force, 1951±53, attaining rank of first lieutenant; member, law firm of Dechert, Price and Rhoads before and after serving two terms as district attorney of Philadelphia, 1966±74; married the former Joan Levy, who was elected to the city council of Philadelphia in 1979; two sons: Shanin and Stephen; served as assistant counsel to the War- ren Commission, 1964; served on Pennsylvania's State Planning Board, The White House Con- ference on Youth, The National Commission on Criminal Justice, and the Peace Corps National Advisory Council; elected to the U.S. Senate, November 4, 1980, for the six-year term begin- ning January 5, 1981; committees: Veterans' Affairs, chair; Appropriations; chair, Judiciary; Governmental Affairs; subcommittees: Agriculture; Rural Development, and Related Agencies; Defense; Foreign Operations; chair, Labor, Health and Human Services; ranking member, Trans- portation; Antitrust, Business Rights, and Competition; Immigration; Technology, Terrorism, and Government Information. Office Listings http://www.senate.gov/∼specter [email protected] 530 Hart Senate Office Building, Washington, DC 20510±3802 ............................... 224±4254 Administrative Assistant.ÐCraig Snyder. FAX: 228±1229 Legislative Director.ÐDan Renberg. Office Manager.ÐJill Schugardt. Press Secretary.ÐJon Ullyot. Suite 9400, 600 Arch Street, Philadelphia, PA 19106 ................................................ (215) 597±7200 Federal Building, Suite 2017, Liberty Avenue/Grant Street, Pittsburgh, PA 15222 . -

Congressional Perspectives on U.S. Policy Toward North Korea and Denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula

Congressional Perspectives on U.S. Policy Toward North Korea and Denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula Kelsey Davenport with Julia Masterson An Arms Control Association Report August 2021 About the Authors Kelsey Davenport is the director for nonproliferation policy at the Arms Control Association, where she focuses on the nuclear and missile programs in Iran, North Korea, India, and Pakistan and on international efforts to prevent proliferation and nuclear terrorism. Julia Masterson is a research associate at the Arms Control Association, where she contributes research and analysis on nonproliferation and chemical weapons issues. Acknowledgements This report was made possible with the support of a generous grant from the Korea Foundation, as well as the support of the members of the Arms Control Association. The authors are responsible for the content of the report, and the statements and views expressed do not necessarily represent the views of the Arms Control Association’s Board of Directors. Cover Photo U.S. Secretary of State Michael R. Pompeo arrives in Pyongyang, North Korea on July 5, 2018. Photo by U.S. Department of State. © Arms Control Association, August 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS 2 Introduction 4 Why Examine the Role of Congress in U.S. Policy on North Korea? 6 Notable Examples of Congressional Engagement on North Korea 14 Survey of Congressional Attitudes, Findings, and Methodology 24 Recommendations for Productively Engaging Congress on North Korea 27 Appendix A: Key Congressional Committees with Jurisdiction on U.S. Policy on North Korea 30 Endnotes Congressional Perspectives on U.S. Policy Toward North Korea and Denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula 1 Introduction ddressing the threat posed by North Korea’s nuclear weapons is one of the most significant and complex challenges facing the United States. -

TK Transcribers 1518 W Porter Street Philadelphia, PA 19145 609-440-2177 2

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF PENNSYLVANIA - - - LOUIS AGRE, : CIVIL NO. 17-4392 et al., : Plaintiff : : : : : v. : : : : : THOMAS W. WOLF, : Philadelphia, Pennsylvania et al., : December 5, 2017 Defendant : 1:03 p.m. - - - TRANSCRIPT AFTERNOON SESSION OF TRIAL DAY 2 BEFORE THE HONORABLE MICHAEL M. BAYLSON, D. BROOKS SMITH, AND PATTY SHWARTZ UNITED STATES JUDGES - - - APPEARANCES: For the Plaintiffs: ALICE W. BALLARD, ESQUIRE Law Office of Alice W. Ballard, P.C. 123 S Broad Street Suite 2135 Philadelphia, PA 19109 THOMAS H. GEOGHEGAN, ESQUIRE MICHAEL P. PERSOON, ESQUIRE SEAN MORALES-DOYLE, ESQUIRE Despres, Schwartz & Geoghegan LTD 77 W Washington St Suite 711 Chicago, IL 60602 TK Transcribers 1518 W Porter Street Philadelphia, PA 19145 609-440-2177 2 1 APPEARANCES: (Continued) 2 BRIAN A. GORDON, ESQUIRE Gordon & Ashworth, P.C. 3 One Belmont Avenue Suite 519 4 Bala Cynwyd, PA 19004 5 For the Defendants: MARK A. ARONCHICK, ESQUIRE 6 MICHELE D. HANGLEY, ESQUIRE Hangley, Aronchick, Segal & 7 Pudlin One Logan Square 8 27th Floor Philadelphia, PA 19103 9 For the Intervenor JASON B. TORCHINSKY, ESQUIRE 10 Defendants: Holtzman, Vogel, Josefiak, Torchinsky, PLLC. 11 45 North Hill Drive Suite 100 12 Warrenton, VA 20186 13 BRIAN S. PASZAMANT, ESQUIRE Blank Rome 14 One Logan Square Philadelphia, PA 19103 15 KATHLEEN A. GALLAGHER, ESQUIRE 16 Cipriani & Werner, P.C. 650 Washington Road 17 Suite 700 Pittsburgh, PA 15228 18 - - - 19 Audio Operator: Janice Lutz 20 Transcribed By: Michael T. Keating 21 - - - 22 Proceedings recorded by electronic sound 23 recording; transcript produced by computer-aided transcription service. 24 - - - 25 Mr. -

House of Representatives 1. Alabama A. Bradly Byrne (Republican) I

House of Representatives 1. Alabama a. Bradly Byrne (Republican) i. Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/byrneforalabama ii. Twitter: https://twitter.com/repbyrne b. Martha Roby (Republican) i. Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/Representative.Martha.Roby ii. Twitter: https://twitter.com/repmartharoby c. Mike Rogers (Republican) i. Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/pages/Mike-Rogers/6406874733 ii. Twitter: https://twitter.com/repmikerogersal d. Robert Aderholt (Republican) i. Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/RobertAderholt ii. Twitter: https://twitter.com/robert_aderholt e. Mo Brooks (Republican) i. Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/RepMoBrooks ii. Twitter: https://twitter.com/repmobrooks f. Gary Palmer (Republican) i. Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/PalmerforAlabama ii. Twitter: https://twitter.com/palmer4alabama g. Teri Sewell (Democrat) i. Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/RepSewell ii. Twitter: https://twitter.com/repterrisewell 2. Alaska a. Don Young (Republican) i. Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/RepDonYoung ii. Twitter: https://twitter.com/repdonyoung 3. Arizona a. Ann Kirkpatrick (Democrat) i. Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/RepKirkpatrick ii. Twitter: https://twitter.com/repkirkpatrick b. Martha McSally (Republican) i. Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/MarthaMcSally ii. Twitter: https://twitter.com/marthamcsally c. Raul Grijalva (Democrat) i. Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/Rep.Grijalva ii. Twitter: https://twitter.com/repraulgrijalva d. Paul Gosar (Republican) i. Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/repgosar ii. Twitter: https://twitter.com/repgosar e. Matt Salmon (Republican) i. Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/RepMattSalmon ii. Twitter: https://twitter.com/repmattsalmon f. David Schweikert (Republican) i. Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/repdavidschweikert ii. Twitter: https://twitter.com/repdavid g. Ruben Gallego (Democrat) i. Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/GallegoforArizona ii.