How Law Enforcement Works with the Private Sector to Prevent Cybercrime

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Politics and Policies

Politics and Policies Rowland-Hite Health Planning Seminar May 6, 2011 2012 Presidential • Obama polls improving – 50% threshold – Tax deal in December – Move to the center – Unhappy base, but no challenger • Republicans – No clear front runner (historic) – Late starting – Significant divisions Political leverage…Senate • What‟s at stake? – 33 seats 23 Democrats 10 Republicans • Democratic vulnerabilities – States where John McCain won in 2008 Joe Manchin (D-WV)…+13 Claire McCaskill (D-MO)…+0.1 Ben Nelson (D-NE)…+14.9 John Tester (D-MT)…+2.3 – States where GOP flipped Senate seats this year Sherrod Brown (D-OH)…Rob Portman (R) Bob Casey (D-PA)…Pat Toomey (R) [Kent Conrad (D-ND)]…Jon Hoeven (R) Herb Kohl (D-WI)…Ron Johnson (R) Political leverage…House 31 new GOP (of 62) representatives who represent districts won by President Obama • FLORIDA • NEW HAMPSHIRE • TEXAS – Daniel Webster – Charlie Bass – Francisco Canseco – Allen West – Frank Guinta – Blake Farenthold • ILLINOIS • NEW JERSEY • VIRGINIA – Robert Dold – Jon Runyan – Scott Rigell – Adam Kinzinger • NEW YORK • WASHINGTON – Randy Hultgren – Ann Marie Buerkle – Jamie Herrera – Bobby Schilling – Chris Gibson • WISCONSIN – Joe Walsh – Richard Hanna – Sean Duffy • KANSAS – Nan Hayworth – Reid Ribble – Kevin Yoder • NORTH CAROLINA • MICHIGAN – Renee Elmers – Dan Benishek • OHIO – Tim Walberg – Steve Chabot • MINNESOTA – Steve Stivers – Chip Cravaack • PENNSYLVANIA • NEVADA – Lou Barletta – Joe Heck – Mike Fitzpatrick – Pat Meehan Multiple opportunities for reducing spending Legislative Platforms • Continuing resolution(s) on appropriations • Debt limit extension(s) • Congressional Budget Resolutions Congressional Budget Resolution • Not a law…does NOT require Presidential signature • Congressional work-plan… guides committees with Rep. Ryan Sen. -

114TH CONGRESS / First Session Available at Frcaction.Org/Scorecard

FRC ACTION VOTE SCORECARD 114TH CONGRESS / First Session Available at FRCAction.org/scorecard U.S. House of Representatives and U.S. Senate Dear Voter and Friend of the Family, FRC Action presents our Vote Scorecard for the First Session of the 114th Congress. This online Scorecard contains a compilation of significant votes on federal legislation affecting faith, family, and freedom that FRC Action either supported or opposed. These recorded votes span the 2015 calendar year and include the greatest number of pro-life votes in history, after the U.S. House increased its Republican membership and the U.S. Senate was returned to Republican control. The year began with a bipartisan effort in the House to prohibit federal funds from being used to pay for abortion coverage under Obamacare. Congress successfully fought to restrict FDA approval of some forms of embryo-destructive research. The House, once again, passed legislation that would prevent late abortions on 5 month old pain-capable unborn children, and although the Senate was unable to pass the bill due to the 60 vote threshold, for the first time, a majority of Senators voted in favor of the bill. The public release of videos revealing Planned Parenthood’s organ harvesting practices renewed efforts to defund this scandal-ridden organization and redirect funding towards community health centers. In an unprecedented victory, the House and Senate passed a budget reconciliation bill, the Restoring Ameri- cans’ Healthcare Freedom Reconciliation Act, which would have eliminated a significant portion of Planned Parenthood’s funding—roughly 80%— and repealed key provisions of Obamacare. -

167 Representatives on FY 07 Animal Welfare Funding Letter

167 Representatives on FY 07 Animal Welfare Funding Letter Arizona Hawaii Missouri Pennsylvania Rep. Raul Grijalva (D) Rep. Ed Case (D) Rep. Russ Carnahan (D) Rep. Robert Brady (D) Rep. Ed Pastor (D) Rep. William Lacy Clay (D) Rep. Mike Doyle (D) Rep. Emanuel Cleaver (D) Rep. Phil English (R) Illinois Rep. Chaka Fattah (D) Arkansas Rep. Judy Biggert (R) Rep. Vic Snyder (D) Rep. Jerry Costello (D) Nevada Rep. Mike Fitzpatrick (R) Rep. Danny Davis (D) Rep. Shelley Berkley (D) Rep. Jim Gerlach (R) Rep. Rahm Emanuel (D) Rep. Todd Platts (R) California Rep. Lane Evans (D) Rep. Allyson Schwartz (D) Rep. Howard Berman (D) New Hampshire Rep. Curt Weldon (R) Rep. Mary Bono (R) Rep. Luis Gutierrez (D) Rep. Charles Bass (R) Rep. Lois Capps (D) Rep. Dan Lipinski (D) Rep. Bobby Rush (D) Rhode Island Rep. Susan Davis (D) New Jersey Rep. Anna Eshoo (D) Rep. Janice Schakowsky (D) Rep. Patrick Kennedy (D) Rep. John Shimkus (R) Rep. Robert Andrews (D) Rep. James Langevin (D) Rep. Sam Farr (D)* Rep. Jerry Weller (R) Rep. Mike Ferguson (R) Rep. Bob Filner (D) Rep. Rush Holt (D) Rep. Elton Gallegly (R) Rep. Frank LoBiondo (R) South Carolina Rep. Michael Honda (D) Indiana Rep. Frank Pallone, Jr. (D) Rep. James Clyburn (D) Rep. Tom Lantos (D) Rep. Dan Burton (R) Rep. Bill Pascrell, Jr. (D) Rep. John Spratt (D) Rep. Barbara Lee (D) Rep. Julia Carson (D) Rep. Joe Wilson (R) Rep. Donald Payne (D) Rep. Zoe Lofgren (D) Rep. Jim Saxton (R) Rep. Doris Matsui (D) Iowa Rep. Christopher Smith (R) South Dakota Rep. -

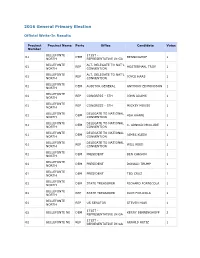

2016 General Primary Write-Ins

2016 General Primary Election Official Write-In Results Precinct Precinct Name Party Office Candidate Votes Number BELLEFONTE 171ST - 01 DEM BENNINGHOF 1 NORTH REPRESENTATIVE IN GA BELLEFONTE ALT. DELEGATE TO NAT'L 01 REP HOSTERMAN, TROY 1 NORTH CONVENTION BELLEFONTE ALT. DELEGATE TO NAT'L 01 REP JOYCE HAAS 1 NORTH CONVENTION BELLEFONTE 01 DEM AUDITOR GENERAL ANTHONY EDMONDSON 1 NORTH BELLEFONTE 01 REP CONGRESS - 5TH JOHN ADAMS 1 NORTH BELLEFONTE 01 REP CONGRESS - 5TH MICKEY MOUSE 1 NORTH BELLEFONTE DELEGATE TO NATIONAL 01 DEM ASH KHARE 1 NORTH CONVENTION BELLEFONTE DELEGATE TO NATIONAL 01 DEM C. ARNOLD MCCLURE 1 NORTH CONVENTION BELLEFONTE DELEGATE TO NATIONAL 01 DEM JAMES KLEIN 1 NORTH CONVENTION BELLEFONTE DELEGATE TO NATIONAL 01 REP WILL REED 1 NORTH CONVENTION BELLEFONTE 01 DEM PRESIDENT BEN CARSON 1 NORTH BELLEFONTE 01 DEM PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP 1 NORTH BELLEFONTE 01 DEM PRESIDENT TED CRUZ 1 NORTH BELLEFONTE 01 DEM STATE TREASURER RICHARD FORNICOLA 1 NORTH BELLEFONTE 01 REP STATE TREASURER RICH FORICOLA 1 NORTH BELLEFONTE 01 REP US SENATOR STEVEN HAIR 1 NORTH 171ST - 02 BELLEFONTE NE DEM KERRY BENNINGHOFF 2 REPRESENTATIVE IN GA 171ST - 02 BELLEFONTE NE REP GERALD RETIZ 1 REPRESENTATIVE IN GA ALT. DELEGATE TO NAT'L 02 BELLEFONTE NE REP BARRY CASPER 1 CONVENTION ALT. DELEGATE TO NAT'L 02 BELLEFONTE NE REP DREW CURTIN 1 CONVENTION ALT. DELEGATE TO NAT'L 02 BELLEFONTE NE REP GERALD RETIZ 1 CONVENTION ALT. DELEGATE TO NAT'L 02 BELLEFONTE NE REP JAMES KLENE 1 CONVENTION ALT. DELEGATE TO NAT'L 02 BELLEFONTE NE REP JIM WORTHINGTON 1 CONVENTION ALT. -

115Th Congress Roster.Xlsx

State-District 114th Congress 115th Congress 114th Congress Alabama R D AL-01 Bradley Byrne (R) Bradley Byrne (R) 248 187 AL-02 Martha Roby (R) Martha Roby (R) AL-03 Mike Rogers (R) Mike Rogers (R) 115th Congress AL-04 Robert Aderholt (R) Robert Aderholt (R) R D AL-05 Mo Brooks (R) Mo Brooks (R) 239 192 AL-06 Gary Palmer (R) Gary Palmer (R) AL-07 Terri Sewell (D) Terri Sewell (D) Alaska At-Large Don Young (R) Don Young (R) Arizona AZ-01 Ann Kirkpatrick (D) Tom O'Halleran (D) AZ-02 Martha McSally (R) Martha McSally (R) AZ-03 Raúl Grijalva (D) Raúl Grijalva (D) AZ-04 Paul Gosar (R) Paul Gosar (R) AZ-05 Matt Salmon (R) Matt Salmon (R) AZ-06 David Schweikert (R) David Schweikert (R) AZ-07 Ruben Gallego (D) Ruben Gallego (D) AZ-08 Trent Franks (R) Trent Franks (R) AZ-09 Kyrsten Sinema (D) Kyrsten Sinema (D) Arkansas AR-01 Rick Crawford (R) Rick Crawford (R) AR-02 French Hill (R) French Hill (R) AR-03 Steve Womack (R) Steve Womack (R) AR-04 Bruce Westerman (R) Bruce Westerman (R) California CA-01 Doug LaMalfa (R) Doug LaMalfa (R) CA-02 Jared Huffman (D) Jared Huffman (D) CA-03 John Garamendi (D) John Garamendi (D) CA-04 Tom McClintock (R) Tom McClintock (R) CA-05 Mike Thompson (D) Mike Thompson (D) CA-06 Doris Matsui (D) Doris Matsui (D) CA-07 Ami Bera (D) Ami Bera (D) (undecided) CA-08 Paul Cook (R) Paul Cook (R) CA-09 Jerry McNerney (D) Jerry McNerney (D) CA-10 Jeff Denham (R) Jeff Denham (R) CA-11 Mark DeSaulnier (D) Mark DeSaulnier (D) CA-12 Nancy Pelosi (D) Nancy Pelosi (D) CA-13 Barbara Lee (D) Barbara Lee (D) CA-14 Jackie Speier (D) Jackie -

TK Transcribers 1518 W Porter Street Philadelphia, PA 19145 609-440-2177 2

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF PENNSYLVANIA - - - LOUIS AGRE, : CIVIL NO. 17-4392 et al., : Plaintiff : : : : : v. : : : : : THOMAS W. WOLF, : Philadelphia, Pennsylvania et al., : December 5, 2017 Defendant : 1:03 p.m. - - - TRANSCRIPT AFTERNOON SESSION OF TRIAL DAY 2 BEFORE THE HONORABLE MICHAEL M. BAYLSON, D. BROOKS SMITH, AND PATTY SHWARTZ UNITED STATES JUDGES - - - APPEARANCES: For the Plaintiffs: ALICE W. BALLARD, ESQUIRE Law Office of Alice W. Ballard, P.C. 123 S Broad Street Suite 2135 Philadelphia, PA 19109 THOMAS H. GEOGHEGAN, ESQUIRE MICHAEL P. PERSOON, ESQUIRE SEAN MORALES-DOYLE, ESQUIRE Despres, Schwartz & Geoghegan LTD 77 W Washington St Suite 711 Chicago, IL 60602 TK Transcribers 1518 W Porter Street Philadelphia, PA 19145 609-440-2177 2 1 APPEARANCES: (Continued) 2 BRIAN A. GORDON, ESQUIRE Gordon & Ashworth, P.C. 3 One Belmont Avenue Suite 519 4 Bala Cynwyd, PA 19004 5 For the Defendants: MARK A. ARONCHICK, ESQUIRE 6 MICHELE D. HANGLEY, ESQUIRE Hangley, Aronchick, Segal & 7 Pudlin One Logan Square 8 27th Floor Philadelphia, PA 19103 9 For the Intervenor JASON B. TORCHINSKY, ESQUIRE 10 Defendants: Holtzman, Vogel, Josefiak, Torchinsky, PLLC. 11 45 North Hill Drive Suite 100 12 Warrenton, VA 20186 13 BRIAN S. PASZAMANT, ESQUIRE Blank Rome 14 One Logan Square Philadelphia, PA 19103 15 KATHLEEN A. GALLAGHER, ESQUIRE 16 Cipriani & Werner, P.C. 650 Washington Road 17 Suite 700 Pittsburgh, PA 15228 18 - - - 19 Audio Operator: Janice Lutz 20 Transcribed By: Michael T. Keating 21 - - - 22 Proceedings recorded by electronic sound 23 recording; transcript produced by computer-aided transcription service. 24 - - - 25 Mr. -

House of Representatives 1. Alabama A. Bradly Byrne (Republican) I

House of Representatives 1. Alabama a. Bradly Byrne (Republican) i. Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/byrneforalabama ii. Twitter: https://twitter.com/repbyrne b. Martha Roby (Republican) i. Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/Representative.Martha.Roby ii. Twitter: https://twitter.com/repmartharoby c. Mike Rogers (Republican) i. Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/pages/Mike-Rogers/6406874733 ii. Twitter: https://twitter.com/repmikerogersal d. Robert Aderholt (Republican) i. Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/RobertAderholt ii. Twitter: https://twitter.com/robert_aderholt e. Mo Brooks (Republican) i. Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/RepMoBrooks ii. Twitter: https://twitter.com/repmobrooks f. Gary Palmer (Republican) i. Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/PalmerforAlabama ii. Twitter: https://twitter.com/palmer4alabama g. Teri Sewell (Democrat) i. Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/RepSewell ii. Twitter: https://twitter.com/repterrisewell 2. Alaska a. Don Young (Republican) i. Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/RepDonYoung ii. Twitter: https://twitter.com/repdonyoung 3. Arizona a. Ann Kirkpatrick (Democrat) i. Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/RepKirkpatrick ii. Twitter: https://twitter.com/repkirkpatrick b. Martha McSally (Republican) i. Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/MarthaMcSally ii. Twitter: https://twitter.com/marthamcsally c. Raul Grijalva (Democrat) i. Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/Rep.Grijalva ii. Twitter: https://twitter.com/repraulgrijalva d. Paul Gosar (Republican) i. Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/repgosar ii. Twitter: https://twitter.com/repgosar e. Matt Salmon (Republican) i. Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/RepMattSalmon ii. Twitter: https://twitter.com/repmattsalmon f. David Schweikert (Republican) i. Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/repdavidschweikert ii. Twitter: https://twitter.com/repdavid g. Ruben Gallego (Democrat) i. Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/GallegoforArizona ii. -

THE ESSENCE of NO LABELS No Labels Is a National Movement of Democrats, Republicans and Independents Dedicated to a New Politics of Problem Solving

THE ESSENCE OF NO LABELS No Labels is a national movement of Democrats, Republicans and independents dedicated to a new politics of problem solving. What exactly is this new politics of problem solving? It’s about an attitude more than anything else. It’s about a willingness to sit down with anyone – conservative, liberal and in between – so long as they are willing to work with you to find solutions. And it’s about recognizing that having principled and deeply held political beliefs doesn’t require an all-or-nothing approach to governance. When No Labels began in 2010, we didn’t have a definitive idea of what the organization and the movement would become. We knew there were millions of people across the country who were frustrated by the dysfunction in our government and who felt they did not have a voice in our political process. And we knew somehow we had to organize this feeling into a coherent national movement that could start to fix our government and secure a stronger future for America. But we’d have to figure out how as we went along – talking to people on Capitol Hill, leaders in state and local government and members of the business and nonprofit communities; and poring through polling data and historical research – to identify the root causes of our government’s problems and what No Labels could do about them. This led us to develop reform plans to fix the dysfunction in our Congress and throughout the federal government and to build a first-of-its-kind bipartisan group of problem solvers on Capitol Hill. -

September 2010 Franklin & Marshall College Poll

For immediate release Thursday, September 23, 2010 September 2010 Franklin & Marshall College Poll SURVEY OF PA 8th Congressional District PRESENTATION OF FINDINGS Prepared by: Center for Opinion Research Floyd Institute for Public Policy Franklin & Marshall College BERWOOD A. YOST DIRECTOR, FLOYD INSTITUTE FOR PUBLIC POLICY DIRECTOR, CENTER FOR OPINION RESEARCH HEAD METHODOLOGIST, FRANKLIN & MARSHALL COLLEGE POLL G. TERRY MADONNA DIRECTOR, CENTER FOR POLITICS AND PUBLIC AFFAIRS DIRECTOR, FRANKLIN & MARSHALL COLLEGE POLL ANGELA N. KNITTLE SENIOR PROJECT MANAGER, CENTER FOR OPINION RESEARCH PROJECT MANAGER, FRANKLIN & MARSHALL COLLEGE POLL KAY K. HUEBNER PROGRAMMER, CENTER FOR OPINION RESEARCH September 23, 2010 Table of Contents METHODOLOGY ............................................................................................................................... 2 KEY FINDINGS ................................................................................................................................... 4 TABLE A-1 – CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT CHOICE DEMOGRAPHICS ............................. 5 MARGINAL FREQUENCY REPORT ............................................................................................. 6 Methodology The survey findings presented in this release are based on the results of interviews conducted September 14-19, 2010. The interviews were conducted at the Center for Opinion Research at Franklin & Marshall College under the direction of the poll’s Director Dr. G. Terry Madonna, Head Methodologist Berwood Yost, -

Tom MARINO Lou BARLETTA

ELECT Governor TOM CORBETT Governor Tom Corbett has worked with the NFIB and its legislative allies to eliminate the state Inheritance Tax for small businesses and farm families, repeal the tax on business loans, and simplify key provisions in the state tax code. Corbett resolved a $4 billion deficit in the state unemployment trust fund without new taxes on employers. He signed three new laws to reduce lawsuit abuse and he enacted reforms to help reduce state regulatory hurdles faced by small businesses. Key Congressional Races Bradford ELECT Potter Tioga Glenn “G.T.” THOMPSON PA-5 Sullivan Montour Lycoming Clinton ELECT Columbia Tom MARINO Union PA-10 Centre Snyder Northumberland ELECT Lou BARLETTA PA-11 Key Pennsylvania Legislative Races ELECT ELECT ELECT ELECT ELECT ELECT Jake Matt Jeff Fred Kurt Tina CORMAN BAKER WHEELAND KELLER MASSER PICKETT SENATE DISTRICT 34 HOUSE DISTRICT 68 HOUSE DISTRICT 83 HOUSE DISTRICT 85 HOUSE DISTRICT 107 HOUSE DISTRICT 110 For a full list of NFIB endorsed candidates, or more detailed information about specific races, please visit NFIB.com/smallbizvoter percent more than the costs to large firms. large to costs the than more percent polling hours, please contact your county elections office. elections county your contact please hours, polling Pennsylvania coal jobs. coal Pennsylvania scientific data before being enacted. being before data scientific employee to small firms is approximately 60 60 approximately is firms small to employee small businesses and jeopardize over 62,000 62,000 over jeopardize and businesses small agencies to base regulations on peer-reviewed peer-reviewed on regulations base to agencies POLLS ARE OPEN 7 A.M. -

Targeting Voters on Television

Targeting Voters on Television Michael G. Hagen Robin Kolodny [email protected] [email protected] Temple University Prepared for delivery at the 2010 Annual Meeting of the Canadian Political Science Association. Concordia University, Montreal, June 1-3. Targeting Voters on Television Michael G. Hagen and Robin Kolodny Temple University Perhaps the most widely noted trend in television in many countries in recent years is the fragmentation of the audience. Regardless of its social consequences, fragmentation is a boon to commercial advertisers who aim to reach a specialized audience—golfers on the Golf Channel, gardeners on Home & Garden TV, gourmets on the Food Network. To the extent that television viewers similarly sort themselves into politically distinctive groups, political advertisers ought to find fragmentation advantageous in the same way. Moreover, just as horizontally integrated firms can advertise golf clubs on one channel and food processors on another, fragmentation may allow political campaigns to deliver messages tailored to particular audiences on television much as they do through other microtargeted means. Our question in this paper is: do they? Do political campaigns exploit the fragmentation of the television audience to focus on some voters but not others and to convey different messages to different segments of the voters on which they do focus? In this paper we begin to take up this question, here focusing on advertising that appeared on cable television, for reasons we will explain. Sources of Data The data for this research are of several types and come from several sources. All pertain to political advertising that appeared during the 2006 campaign in the Philadelphia media market. -

October 2006 SMART Transportation Newsletter

Volume 38 October 2006 Number 10 www.utuia.org www.utu.org The Official Publication of the United Transportation Union THE VOICE OF TRANSPORTATION LABOR “If we are to walk a common path to a bright future, we must exercise our power at the ballot box and help to elect labor-friendly members to Congress.” – UTU International President Paul Thompson Your job + your family + your future = YOUR VOTE. Support the candidates who support you! NEGOTIATIONS UPDATE Help yourselves: Support The national-agreement negotiating teams from the UTU and the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers and Trainmen labor-friendly candidates met jointly last month with the National Car- riers’ Conference Committee, which repre- Congressional elections have direct conse- •Export of jobs; sents most of the major railroads and many quences for each of us and our families. •Weakening of laws that protect workers’ smaller ones. This Election Day, Nov. 7, is going to be a rights to organize. test for labor. Those who control the new Con- “This was an unprecedented show of In the centerspread of this issue of UTU gress seated in 2007 will have a direct influ- operating-craft solidarity,” said UTU Inter- News is a listing of labor-friendly candidates as ence on our job security, our health care, our national President Paul Thompson, who sat determined by UTU state legislative directors pensions and our workplace safety. beside BLET President Don Hahs, while and our national legislative office. The list is other members of the UTU and BLET nego- If working families unite to vote for labor- bi-partisan.