Fragmenting and Healing Bodies in the Early Modern Bay of Kotor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Izmjene I Dopune Prostornog Plana Opštine Kotor Za Područje Vranovići - Pobrdje

Izmjene i dopune Prostornog plana opštine Kotor za područje Vranovići - Pobrdje IZMJENE I DOPUNE PROSTORNOG PLANA OPŠTINE KOTOR ZA PODRUČJE VRANOVIĆI - POBRDJE 2008. Naručilac: SKUPŠTINA OPŠTINE KOTOR Obradjivač: MONTECEP – CENTAR ZA PLANIRANJE URBANOG RAZVOJA Kotor (Poštanski fah 76) Benovo 36 Radni tim Saša Karajović, dipl. prostorni planer (odgovorni planer) broj licence: 05-5295/05-1 (09/01/06) Zorana Milošević, dipl. ing. arhitekture broj licence: 01-1871/07 (21/03/07) Jelena Franović, dipl. ing. pejzažne arhitekture broj licence: 01-1872/07 (21/03/07) Edvard Spahija, dipl. ing. saobraćaja broj licence: 05-1355/06 (15/05/06) Svjetlana Lalić, dipl. ing. građevine broj licence: 01-10693/1 (18/01/08) Bojana Gobović, dipl. ing. građevine Predrag Vukotić, dipl. ing. elektrotehnike broj licence: 01-10683/1 (25/01/08) Zoran Beljkaš, dipl. ing. elektrotehnike broj licence: 01-6809/1 (05/10/07) Rukovodilac MonteCEP-a: Saša Karajović, dipl. prostorni planer MonteCEP - Kotor, 2008. 1 Izmjene i dopune Prostornog plana opštine Kotor za područje Vranovići - Pobrdje MonteCEP - Kotor, 2008. 2 Izmjene i dopune Prostornog plana opštine Kotor za područje Vranovići - Pobrdje SADRŽAJ ELABORATA UVODNE NAPOMENE 4 Pravni osnov Povod za izradu plana Cilj izrade Obuhvat i granica plana Postojeća planska dokumentacija Sadržaj planskog dokumenta Programski zadatak IZVOD IZ PROSTORNOG PLANA OPŠTINE KOTOR (1995.) 7 ANALIZA I OCJENA POSTOJEĆEG STANJA PROSTORNOG UREĐENJA PROGRAMSKA PROJEKCIJA EKONOMSKOG I PROSTORNOG RAZVOJA PROJEKCIJE RAZVOJA STANOVNIŠTVA RAZRADA -

A Few Extra Touches

Extra touches #1 Lustica peninsula Adventure Lustica is a peninsula on the south Adriatic Sea in Montenegro, located at the entrance of the Bay of Kotor. The peninsula has an area of 47 km² and is 13 km long. The highest point of the peninsula is Obosnik peak, at 582 m. It has 35 km of coast or 12% of Montenegrin coastline. Activities : Quads, bikes and e-bikes at Lustica Degustation of local products in Organic Olive Farm of Family MORIC The family Moric has an organic olive farm and the main occupation is producing certified organic olive oil in Montenegro, branded as “Moric Organic”. As a family business for more than 3 centuries, the farm is certified by national certification body Monteorganica and registered by Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development of Montenegro. That small farm covers cca 6ha and counts 1000 trees. Most of them are more than 350 years old. Apart of the olive oil, there is also a production of table olives. Photostop on Arza Fortress Driving countinues to Arza fortress. Photostop and glass of non-alcholic champagne. Fort Arza was built during the Austro Hungarian period and is located at the entrance to the Herceg Novi bay, on the edge of Luštica peninsula as the tip of the defense against potential conquerors. A firm stone building with a view on the far surroundings, reaching as far as Cape Ostro (Croatian border). Fort Arza was built on a layer of rocks that serve as an eternal protector of this fortress from the force of waves and time. -

See Kotor Bay

A MAGAZINE OF THE HERALD-TRIBUNE MEDIA GROUP MARCH 2017 STYLE CONTENTS FEATURES DEPARTMENTS Style up front 10 Editor’s note All about friendship. 12 Calendar Style around town 14 Arts News and events from the performing and visual arts. 16 New in town New people, places and things. 18 At lunch Meet A.G. Lafley, former head of Procter & Gamble, and the man behind the Bayfront 20:20 mission. Style home 40 Home It was the perfect house, on the perfect street, in the perfect neighborhood for 20 this discerning couple. Living in style Perfectly suited If it’s March, then swimsuit season is just around the corner, and it’s time to start looking at this 48 Travel We depart for the breathtakingly year’s latest styles. While designers continue to get more and more creative with their one-piece beautiful Montenegro. suits, it is bikinis that are this year’s stars on the fashion runway. By Terry McKee. Photography by 54 Food Darwin Santa Maria is back — this time Barbara Banks. on Siesta Key with Cevichela. Personal style 56 Beauty Tips for before, during and after fun in the sun. 57 Health & Wellness Ketamine … a ground- breaking new treatment for depression and chronic pain. 58 Shopping Gifts for him, her and the home. 60 Closet envy The classic style of Sydney Goldstein. 62 Out & About What’s happening on the social scene. 70 Palm Trees & Pearls The art of entertaining. 72 Astrology What the stars and planets have 28 34 to say. 74 Yesteryear So long, Ringling Bros. -

PROGRESS REPORT 2012 and 2013

Njegoseva Street, 81250 Cetinje National Commission Phone/Fax: +382 41 232 599 of Montenegro e-mail: [email protected] for UNESCO United Nations No.: ()I- ~~ -l Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization Date: Z. ~ I 20119 United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization THE WORLD HERITAGE CENTRE -Attn: Mr. Kishore Rao, Director - PARIS Dear Director, We are pleased to send you herewith attached the Report on state of conservation of the Natural and Culturo- Historical Region of Kotor done in accordance with the Decision 36 COM 78.79. Along with the Report we are sending the revised Retrospective Statement of Outstanding Universal Value done in respect to !COM OS comments. I would like to take this opportunity to thank you and your team for your kind help and continuous support in the implementation of the World Heritage Convention in Montenegro. I mmission CC: Ambassador Irena Radovic, Permanent Delegation of Montenegro to UN ESCO Ambassade du Montenegro 216, Boulevard Saint Germain 75007 Paris Tel: 01 53 63 80 30 Directorate for Conservation of Cultural Properties Territorial Unit in Kotor NATURAL AND CULTURAL-HISTORICAL REGION OF KOTOR, MONTENEGRO C 125 PROGRESS REPORT 2012 and 2013 February 1st, 2014 Area of World heritage of Kotor Progress Report 2012 and 2013 C O N T E N T I. Introduction II. Answer on the world heritage committee's decisions no. 36 COM 7 B.79 III. Activities regarding conservation and improvement of the Kotor World Heritage IV. Conservation – restoration treatment of cultural properties V. Archaeological researches Page 2/34 Area of World heritage of Kotor Progress Report 2012 and 2013 I. -

Montenegro & the Bay of Kotor

SMALL GROUP Ma xi mum of LAND 28 Travele rs JO URNEY Montenegro & the Bay of Kotor Inspiring Moments > Visit Venetian-era towns along the Bay of Kotor, a beautiful blue bay cradled between plunging emerald mountains. > Delight in Dubrovnik’s magnificent architecture, towering city walls and INCLUDED FEATURES limestone-paved Stradun. Accommodations (with baggage handling) Itinerary > Sip Montenegrin wines and learn about – 6 nights in Tivat, Montenegro, at the Day 1 Depart gateway city Montenegro’s long tradition of viticulture at deluxe Regent Porto Montenegro. Day 2 Arrive in Dubrovnik and one of Eastern Europe’s finest vineyards. – 1 night in Dubrovnik, Croatia, at the transfer to hotel in Tivat > Discover the serene ambience of two deluxe Hilton Imperial Dubrovnik. Day 3 Cetinje enchanting Orthodox monasteries. > Revel in the remarkable ecosystem and Transfers (with baggage handling) Day 4 Perast | Kotor – Deluxe motor coach transfers during the Day 5 Lake Skadar | Tuzi unspoiled natural beauty of Lake Skadar. Land Program. Day 6 Tivat | Kotor > Step inside a restored Yugoslav submarine at the Maritime Heritage Museum. Extensive Meal Program Day 7 Budva > Uncover the proud history of – 7 breakfasts, 4 lunches and 3 dinners, Day 8 Dubrovnik Cetinje, Montenegro’s cultural center. including Welcome and Farewell Dinners; Day 9 Transfer to Dubrovnik airport tea or coffee with all meals, plus wine and depart for gateway city > Experience two UNESCO World with dinner. Heritage sites. Flights and transfers included for AHI FlexAir participants. Your One-of-a-Kind Journey Note: Itinerary may change due to local conditions. – Discovery excursions highlight the local Activity Level: We have rated all of our excursions with Our Lady of the Rocks culture, heritage and history. -

1169. Na Osnovu Člana 95 Tačka 3 Ustava Crne Gore Donosim UKAZ O

1169. Na osnovu člana 95 tačka 3 Ustava Crne Gore donosim UKAZ O PROGLAŠENJU ZAKONA O ZAŠTITI PRIRODNOG I KULTURNO- ISTORIJSKOG PODRUČJA KOTORA Proglašavam Zakon o zaštiti prirodnog i kulturno-istorijskog područja Kotora, koji je donijela Skupština Crne Gore 25. saziva, na trećoj sjednici drugog redovnog (jesenjeg) zasijedanja u 2013. godini, dana 20. novembra 2013. godine. Broj: 01-1826/2 Podgorica, 3. decembra 2013. godine Predsjednik Crne Gore, Filip Vujanović, s.r. Na osnovu člana 82 stav 1 tačka 2 Ustava Crne Gore i Amandmana IV stav 1 na Ustav Crne Gore, Skupština Crne Gore 25. saziva, na trećoj śednici drugog redovnog (jesenjeg) zasijedanja u 2013. godini, dana 20. novembra 2013. godine, donijela je ZAKON O ZAŠTITI PRIRODNOG I KULTURNO-ISTORIJSKOG PODRUČJA KOTORA I .OSNOVNE ODREDBE Predmet Član 1 Ovim zakonom se uređuju zaštita, upravljanje i posebne mjere očuvanja prirodnog i kulturno – istorijskog područja Kotora (u daljem tekstu: Područje Kotora), koje je kao prirodno i kulturno dobro upisano na Listu svjetske baštine UNESCO. Određivanje područja Član 2 Područje Kotora obuhvata: Stari grad Kotor, Dobrotu, Donji Orahovac, dio Gornjeg Orahovca, Dražin Vrt, Perast, Risan, Vitoglav, Strp, Lipce, Donji Morinj, Gornji Morinj, Kostanjicu, Donji Stoliv, Gornji Stoliv, Prčanj, Muo, Škaljare, Špiljare i morski basen Kotorsko - Risanskog zaliva. Granica Područja Kotora ide graničnim parcelama katastarske opštine Škaljari II, počev od tromeđe katastarskih opština Škaljari II sa K.O: Mirac i K.O. Dub i pruža se u pravcu sjevera i sjeverozapada, zapadnim i jugozapadnim granicama graničnih parcela katastarskih opština K.O. Škaljari, K.O. Muo, K.O. Prčanj II, K.O. Stoliv II, odnosno administrativnom granicom opština Kotor i Tivat i spušta se do svjetionika na Verigama. -

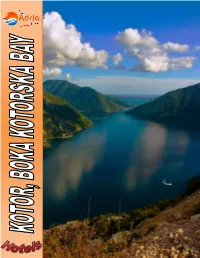

Kotor and Bay of Kotor

Kotor and Bay of Kotor Travel agency „Adria Line”, 13 Jul 1, 85310 Budva, Montenegro Tel: +382 (0)119 110, +382 (0)67 733 177, Fax: +382 (0)33 402 115 E-mail: [email protected], Web: www.adrialine.me Kotor and Bay of Kotor Kotor and The Kotor Bay Kotor Bay Boka Bay, one of the world’s 25 most beautiful bays and protected UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1979. Due to its unusual look, exceptional cultural and natural features the bay is often called Europe`s southernmost fjord, but in fact it`s a submerged river canyon. The bay is composed of 4 smaller bays - Tivat, Herceg Novi, Risan and Kotor bay. The narrowest part of the bay, Verige strait, divides it into the inner and outer part. Boka Bay glows with amazing calmness and peace. Located between the Adriatic Sea and the vide limestone area the region of Boka Kotorska is under a strong influence of Mediterranean and Mountain climate. That special climate blend creates a distinguished Sub- Mediterranean climate quite different from other part of Montenegrin coast. Unique feature for Boka is the early spring when all surrounding mountains are still covered with snow while the coast flourishes with Mediterranean trees and flowers in blossom. During the winter one can enjoy the pleasant sun and calm weather on the coast while to the mountains and snow takes just 1 hour of slow drive. Along the whole coast line of the bay exist the rich distribution of Mediterranean, continental and exotic vegetation such as laurels, palms, olive-trees, orange and lemon trees, pomegranate trees, agaves, camellias, mimosas… The bay has been inhabited since antiquity and has some well preserved medieval towns. -

Montenegrin-Russian Relations and Montenegro's

31 ZUZANA POLÁČKOVÁ – PIETER VAN DUIN The dwarf and the giant: Montenegrin-Russian relations and Montenegro’s ‘cult of Russia’, c. 1700-2015 This article tries to make an analysis of a rather special political and historical phenomenon: the, perhaps, unique relationship between Montenegro and Russia as it evolved during a period of three centuries. This connection can be described as one between a dwarf and a giant, as an asymmetrical re- lationship with an ideological as well as a pragmatic dimension that was attractive for both parties. The origin of direct Montenegrin-Russian relations can be found in the early years of the eighteenth century, the era of Peter the Great and of a new stage in Montenegrin political history and state consolidation. This ‘founding period’ has to be paid particular attention to, in order to understand the relationship that followed. In the special political and cultural conditions of an increasingly expansionist Montenegro, the ‘cult of Russia’ emerged as an ideological, but also functional, ritual to reinforce Montenegro’s efforts to survive and to become a more important factor in the western Balkans region. But the tiny principal- ity was dependent on the vagaries of international politics and Russian policy. The dwarf aspired to be a little Russia and to emulate the giant. A clear definition of friend and foe and a policy of territorial expansion were seen as part of this. On the level of national-cultural identity this led to a politicisation of the Orthodox faith. In the ideological sphere it also meant the building of a mythical past to legitimise an expansionist ethos of often-irresponsible dimensions. -

BOKELJI IZMEĐU BOKE I TRSTA Boka – Kotorska Men Between the Bay of Kotor and Trieste

* Vesna Čučić PRONICANJE U PROŠLOST ISSN 0469-6255 (77-88) BOKELJI IZMEĐU BOKE I TRSTA Boka – Kotorska Men Between The Bay of Kotor and Trieste UDK 908 Boka Kotorska Izvorni znanstveni članak Original scientific paper Sažetak foundation of steamship company Austrian Lloyd in 1833. Odnosi Boke kotorske i Trsta počinju biti intenzivniji with its seat in Trieste as the first, unique and the biggest tek u 19. stoljeću nakon propasti Mletačke Republike i s steamship company at the Adriatic, made Trieste the dolaskom austrijske vlasti u Boku. most developed maritime center at the Eastern part of the Adriatic. The owners of Boka sold their sailing ships Krajem 18. stoljeća Boka je imala oko 300 jedrenjaka. and their sons started working in Lloyd of Austria. Godine 1805. imala je 400 brodova s patentom*, 290 Altough that steamship company was one of the causes brodova bez patenta i 3.000 pomoraca. Ali nakon of the fall of Boka Kotorska seafaring, however thus Boka Napoleonovih ratova, 1814. godine Boka spala je na 50 Kotorska captains contributed to its flourishment. brodova s patentom i 221 brod bez patenta. In Trieste, around the middle of the 19th ct. there Austrija, koja je prije gospodarila samo Hrvatskim flourished the houses of Boka Kotorska families Florio, primorjem, Rijekom i Trstom, postala je gospodaricom Verona, Vizin and Tripković. cijele obale od Venecije do Budve. Austrijsko favoriziranje Trsta i osnutak parobrodarskoga društva Austrijski Lloyd 1833. godine sa sjedištem u Trstu, kao prvoga, jedinog i najvećeg parobrodarskog društva na 1. Boka kotorska početkom 19. stoljeća Jadranu, učinilo je da Trst postane najrazvijenije pomorsko središte na istočnoj obali Jadrana. -

Lokalni Izbori – Rezultati Stranaka Avgust 2020

OPŠTINA KOTOR LOKALNI IZBORI – REZULTATI STRANAKA AVGUST 2020. 9. 2. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 1. 3. Broj VLADIMIR JOKIĆ – „KOTOR JE „SDP – dr Ivan Ilić – Socijaldemokrate ZA BUDUĆNOST – Za liberalni Kotor – DR BRANKO BAĆO Važećih Nevažećih Za Kotor! Za Crnu Goru! URA KOTOR „PATRIOTSKI I HGI – Svim srcem birač. NAŠA NACIJA“ – DEMOKRATE – dr Andrija Lompar – Andrija Pura Popović – IVANOVIĆ – Naziv biračkog mjesta GRAĐANSKI – CRNO NA JAK KOTOR!“ KOTORA gl. listića gl. listića – DEMOKRATSKA CRNA DPS Milo Đukanović za Kotor! mjesta BIJELO" Mi odlučujemo dosljedno Liberalna partija SOCIJALISTI GORA za Kotor DOBROTA 1 FAKULTET ZA POMORSTVO (A-K) 433 3 121 161 34 14 25 45 12 10 11 DOBROTA 2 FAKULTET ZA POMORSTVO (L-Š) 472 8 130 197 19 22 19 52 3 18 12 DOBROTA 3 DOM KULTURE (A-G) 591 13 179 208 28 21 27 83 9 23 13 DOBROTA 4 DOM KULTURE (D-K) 678 9 193 249 34 42 28 88 5 19 20 DOBROTA 5 DOM KULTURE (L-M) 446 2 117 151 35 17 24 72 9 12 9 DOBROTA 6 DOM KULTURE (N-R) 557 11 147 201 28 35 20 78 7 26 15 DOBROTA, SV. STASIJE 7 ZGRADA JUGOOCEANIJE, BIVŠA .PR. "SERVO MIHALJ" (A-K) 488 6 131 163 27 18 36 65 3 24 21 DOBROTA, SV. STASIJE 8 ZGRADA JUGOOCEANIJE, BIVŠA .PR. "SERVO MIHALJ" (L-Š) 633 7 143 254 40 29 39 66 6 39 17 STARI GRAD 9 KULTURNI CENTAR – ULAZNI HOL (A-LJ) 556 15 138 165 40 42 37 85 8 27 14 STARI GRAD 10 KULTURNI CENTAR – GALERIJA (M-Š) 542 11 120 190 43 20 27 61 21 43 17 ŠKALJARI 11 DOM KULTURE (A-J) 504 12 76 184 38 45 32 64 24 26 15 ŠKALJARI 12 DOM KULTURE (K-O) 484 4 128 190 33 10 27 65 4 18 9 ŠKALJARI 13 DOM KULTURE (P-Š) 644 11 123 274 29 35 31 -

Montenegro: Vassal Or Sovereign?

Scholars Crossing Faculty Publications and Presentations Helms School of Government January 2009 Montenegro: Vassal or Sovereign? Octavian Sofansky Stephen R. Bowers Liberty University, [email protected] Marion T. Doss, Jr. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/gov_fac_pubs Part of the Other Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons, Political Science Commons, and the Public Affairs, Public Policy and Public Administration Commons Recommended Citation Sofansky, Octavian; Bowers, Stephen R.; and Doss, Jr., Marion T., "Montenegro: Vassal or Sovereign?" (2009). Faculty Publications and Presentations. 28. https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/gov_fac_pubs/28 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Helms School of Government at Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Montenegro: Vassal or Sovereign? 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY................................ ................................ ............... 3 INTRODUCTION ................................ ................................ ......................... 4 STRATEGIC SIGNIFICANCE OF MONTENEGRO................................ .............. 6 INTERNAL POLITICAL DUALISM ................................ ................................ 12 RUSSIAN POLICY TOWARDS THE BALKANS................................ ............... 21 MULTILATERAL IMPLICATIONS -

Discover the Enchanting Village Life of Kotor and Montenegro

KOTOR MONTENEGRO Discover the enchanting village life of Kotor and Montenegro. Journey through the mountain towns of Montenegro, a winsome country full of history and tradition, on the coast of the Adriatic. The main port city of Kotor bustles at the foot of Mount Orjen, where deep waters submerge an ancient river canyon. Surrounded by impressively high medieval walls, the town is a welcoming juncture of ethnic Montenegrins, Serbians, Croatians, Romani and others. Old Town Kotor is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, restored after a 1979 earthquake damaged parts of its Romanesque churches, iconographic monuments and medieval buildings. Today, the port is the gateway to a chain of humble, yet beautiful and enriching mountain hamlets where old customs are still part of daily life. LOCAL CUISINE SHOPPING Kotor’s unique culinary staples are pure Shop Old Kotor for comfort food. Try any of a variety of endless possibilities. stewed dishes. Boiled lamb with vegetables, Boutiques, galleries, lamb cooked in milk, and pork stew with cafes and shops rastan, a dark leafy green, infuse the start within walking native diet with savory warmth. Ask for distance of the pier. the catch of the day in any restaurant, Once inside the too — grilled fish is delicious here. walls of the town, even more options For quicker fare, hit a local grill. Regular favorites include unfold. Look for pljeskavica, a lamb, pork and beef burger, or ćevapi, minced high-end Italian pork and beef in bun with grilled onions and sour cream. labels lining the streets next to Pair food with wine here.