The Dilemma of Aural Skills Within Year Eleven Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Music Man Stingray Music Man Stingray 11.07.16 08:15 Seite 80

Music Man StingRay_Music Man StingRay 11.07.16 08:15 Seite 80 STECHROCHEN DELUXE Music Man StingRay Guitar Der Begriff StingRay ist fast schon zu einem Synonym für Bass geworden. Wir verbinden ihn mit prominenten Musikern wie Flea von den Red Hot Chili Peppers oder mit Tony Levin. Der zeitgleich ins Leben gehobenen StingRay-Gitarre blieb der Weg ins Scheinwerferlicht allerdings versagt. Vielleicht ist die Zeit jetzt aber reif für eine Wiedereinführung. TEXT Franz Holtmann ❙ FOTOS Dieter Stork Mit einer modernisierten Konzeption soll Halsplatte fest auf den Korpus ge- das Gitarrenmodell StingRay im Rahmen schraubt. Die parallel nach hinten ver- der Modern Classic Collection nun erneut setzte Kopfplatte folgt der modernen auf den Weg gebracht werden. Wäre ja Formgebung späterer Music-Man-Ent- wirklich nicht das erste Design, das nach würfe mit 4 zu 2-Anordnung der Mecha- anfänglichen Problemen mit der Akzep- niken (Schaller M6 Locking), ist aber tanz dann doch noch in die Spur findet. etwas größer ausgelegt. Die Saiten brin- gen durch ihre kurzen Wege mit geradem Zug ausreichenden Andruck auf den Sat- face- und sound-lifting extra tel, was die Montage eines String Trees Der grundlegende Entwurf der StingRay zur Saitenniederhaltung erübrigt. Für das Guitar ist also nicht gerade neu, aller- ordentlich dicke Griffbrett nahm man ost- dings wurde Wesentliches wie Halsbefes- indischen Palisander, an dessen 10"-Ra- tigung, Kopfplattengestaltung und elek- dius 22 Bünde aus Edelstahl (medium- trische Ausstattung grundlegend geän- high-profile) perfekt angepasst wurden. dert, ganz abgesehen davon, dass eine Dots an den üblichen Stellen kennzeich- Schraubhalsgitarre mit Mahagoni-Body nen die Lagen. -

Micionlms International SCO N

INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark, it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed. For blurred pages, a good image of the page can be found in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted, a target note will appear listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photographed, a definite method of “sectioning” the material has been followed. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand comer of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again-beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. -

READ IT and SLEEP by William L

Home where I was raised. Roundeau Ranch, Tygh Ridge, Wasco County, Oregon. READ IT AND SLEEP By William L. (Bill) Hulse I was born in Sherman County on August 4, 1920 to Roy Paul and Mary Jane Hulse. Dad was a farmer and storekeeper and mother was a schoolteacher. They moved from Sherman County to Tygh Ridge in Wasco County in the winter of 1919 and 1920. Mother had been doctoring in Moro with Dr. Poly, so she went back to Moro for my birth. Both my brother Paul and sister Janet were born in Sherman County. We lived on and farmed the old Roundeau Ranch, which had been purchased by Al- fred Dillinger. In the early part of the depression the ranch was lost to the Eastern Oregon Land Company. Dad eventually purchased it from them and then added the Murdock McLeod homestead. We attended Harmony Grade School, one and a quarter miles from our house. My grandkids would say “I suppose it was uphill both ways and through two feet of snow?” It wasn’t that bad, but we did walk. The school had one room and one teacher who was the janitor, nurse and mother hen to all of us kids. I remember one year – there were thirteen children in seven grades. There was no first grade that year. There were children from the family of George Hillgen, Walt Hillgen, Ellis Jones, Tommy Jones, Sid Baker, Clarence Garner, Joe McMurray and Roy Hulse. The teacher’s salary started at $50 per month and board and room. We had several local teachers: Beula Fraley McClean, Mary Sigman Hart, Opal Bene- dict Wiidanen and Frances Doud. -

Front Matter Template

Copyright by Martin Norgaard 2008 The Dissertation Committee for Martin Norgaard Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Descriptions of Improvisational Thinking by Artist-level Jazz Musicians Committee: Robert A. Duke, Co-Supervisor Laurie S. Young, Co-Supervisor Lowell J. Bethel Eugenia Costa-Giomi Jeffrey L. Hellmer Judith A. Jellison Bruce W. Pennycook Descriptions of Improvisational Thinking by Artist-level Jazz Musicians by Martin Norgaard, M.A., B.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August, 2008 Dedication Jonna Hindsgaul Kai Nørgaard Leif Hindsgaul Descriptions of Improvisational Thinking by Artist-level Jazz Musicians Publication No._____________ Martin Norgaard, Ph.D. The University of Texas at Austin, 2008 Supervisors: Robert A. Duke and Laurie S. Young I investigated the thought processes of seven artist-level jazz musicians. Although jazz artists in the past have spoken extensively about the improvisational process, most have described improvisation only in general terms or have discussed specific recorded improvisations long after the recordings had been made. To date, no study has attempted to record artists’ perceptions of their improvisational thinking regarding improvisations they had just performed. Seven jazz artists recorded an improvised solo based on a blues chord progression accompanied only by a drum track. New technologies made it possible to notate the recorded material as it was being performed. After completing their improvisations, participants described in a directed interview, during which they listened to their playing and looked at the notation of their solos, the thinking processes that led to the realization of their performances. -

Veteran Educators' Perceptions of the Internet's Impact on Learning and Social Development Matthew Incev Nt Glowiak Walden University

Walden University ScholarWorks Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection 2014 Veteran Educators' Perceptions of the Internet's Impact on Learning and Social Development Matthew inceV nt Glowiak Walden University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations Part of the Elementary and Middle and Secondary Education Administration Commons, Elementary Education and Teaching Commons, Other Communication Commons, and the Social Psychology Commons This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection at ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Walden University College of Counselor Education & Supervision This is to certify that the doctoral dissertation by Matthew Glowiak has been found to be complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the review committee have been made. Review Committee Dr. Stacee Reicherzer, Committee Chairperson, Counselor Education and Supervision Faculty Dr. Laura Haddock, Committee Member, Counselor Education and Supervision Faculty Dr. Barbara Benoliel, University Reviewer, Counselor Education and Supervision Faculty Chief Academic Officer Eric Riedel, Ph.D. Walden University 2014 Abstract Veteran Educators' Perceptions of the Internet's Impact on Learning and Social Development by Matthew V. Glowiak MS, Walden University, 2010 BS, University of Illinois, 2005 Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Counselor Education & Supervision Walden University December 2014 Abstract In a time where some 2.4 billion Internet users exist worldwide, children are increasingly impacted by the Internet's influence, both directly and indirectly. -

The Inclusive Experience in British Progressive Rock of the 1960S and 1970S

Listening to images, reading the records: The inclusive experience in British progressive rock of the 1960s and 1970s Tymon Adamczewski, Kazimierz Wielki University in Bydgoszcz Abstract The article concerns the form of experience offered by the British progressive rock of the late 1960s and early 1970s in the light of the tendency to view the genre through the prism of modernism. The materiality of key musical albums within the genre—through elaborate aesthetic construction and reliance on literary ideas—played an indispensable role in interacting with the records. I argue that through constructing a narrative message in the form of record covers, progressive rock could be treated as a literary form which functions according to what Nicholas Royle describes as veering and which allows to avoid problems associated with considering the genre as modern or postmodern. Key words: experience, progressive rock, veering, postmodernism Introduction The two paintings have a lot in common: an attempt to render feelings of distress, desperation and a sense of urgency in reaching out to the audience. Both are images of iconic status; both are similarly expressionistic in representing their subject matter and, significantly, both depict screaming figures. In fact, the paintings in question, Edvard Munch’s The Scream (1893) and the cover of King Crimson’s In the Court of the Crimson King (1969), are not only documents of their zeitgeist but may still have an important story to tell about the overlapping areas in the experience of images, music and words. Munch’s chronologically earlier painting, widely acknowledged as an epitome of modernist art, is an easily identifiable inspiration for Barry Goldber’s emblematic record cover of what is often considered as one of the defining examples of progressive rock. -

MTO 22.3: Steinbeck, Talking Back

Volume 22, Number 3, September 2016 Copyright © 2016 Society for Music Theory * Paul Steinbeck NOTE: The examples for the (text-only) PDF version of this item are available online at: http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.16.22.3/mto.16.22.3.steinbeck.php KEYWORDS: Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM), audience, improvisation, interaction, Roscoe Mitchell, “Nonaah,” performance, repetition, sound, timbre, variation ABSTRACT: Many music scholars, particularly in jazz studies, have investigated performers’ real-time sonic interactions with one another. Very few, though, have asked how musicians interact with their audiences. The following article examines a performance that demands this kind of analysis: a 1976 concert in which saxophonist Roscoe Mitchell is confronted by an audibly hostile audience. Received December 2015 Willisau [1] Roscoe Mitchell was minding his own business. He and his bandmates in the Art Ensemble of Chicago were one month into a long tour of Europe, and as August 1976 came to a close, they were enjoying a rare weekend off (Janssens and de Craen 1983). The members of the Art Ensemble decided to spend their downtime in Willisau, Switzerland. A picturesque village near Lucerne, Willisau was home to one of the largest European jazz festivals of 1976, along with San Sebastián, Pescara, Montreux, Moers, Juan-les-Pins, and Châteauvallon (“Festivals” 1976, 4–6). The Art Ensemble performed at Châteauvallon on August 22, then headed to Switzerland, where they opened the Willisau festival on August 26 (Flicker et al. 1976, 10 and 13; Hardy 1976, 19). Their next concert—in Italy—was still a few days away, so the musicians stayed in Willisau to experience the rest of the festival. -

The GRAMMY Museum and Queens Museum to Celebrate The

The GRAMMY Museum® and Queens Museum To Celebrate the Ramones' 40th Anniversary With A New Two-Part Exhibition Hey! Ho! Let’s Go: Ramones and the Birth of Punk Debuts April 10, 2016 at Queens Museum in New York and in Los Angeles at the GRAMMY Museum on Oct. 21, 2016 LOS ANGELES/QUEENS (January 27, 2016) — The GRAMMY Museum® in Los Angeles and the Queens Museum in New York have announced they are partnering to present an unprecedented two-part exhibition celebrating the lasting influence of punk rock progenitors the Ramones. Hey! Ho! Let's Go: Ramones and the Birth of Punk will open on April 10, 2016, at the Queens Museum in New York. It then moves to Los Angeles on Oct. 21, 2016, where the second part will debut at the GRAMMY Museum in Los Angeles. The two-part exhibition, co-curated by the GRAMMY Museum at L.A. LIVE and the Queens Museum, in collaboration with Ramones Productions Inc., will commemorate the 40th anniversary of the release of the Ramones' 1976 self-titled debut album and will explore the lasting influence the punk rockers had on their hometown, from their start in Queens to their history-making performances at CBGB, highlighting their musical achievements, with a special influence on the dynamic synergy between New York City's music and visual arts scenes in the 1970s and 1980s. While the exhibition's two parts will share many key objects drawn from more than 50 public and private collection across the world, each will explore the Ramones through a different lens: The Queens Museum iteration will begin with their roots in Queens and reveal their ascendancy in both music and visual culture, while the GRAMMY Museum version will contextualize the band in the larger pantheon of music history and pop culture. -

Food Consumption

Class, Food, Culture Exploring ‘Alternative’ Food Consumption by Jessica Paddock Cardiff University This thesis on submitted to Cardiff University in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR IN PHILOSOPHY September 2011 i DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed …………………………………………………………. (candidate) Date ………………………… STATEMENT 1 This thesis is being submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD. Signed …………………………………………………………. (candidate) Date ………………………… STATEMENT 2 This thesis is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by footnotes giving explicit references. Signed …………………………………………………………. (candidate) Date ………………………… STATEMENT 3 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed …………………………………………………………. (candidate) Date ………………………… i Acknowledgements There are many who are to be thanked for their support in helping me to start, write-up and submit this thesis. First of all, thank you to the participants, producers, volunteers and stakeholders who made this research both fun as well as feasible. I am also very grateful to my supervisors Professor Susan Baker and Dr. Bella Dicks for being generous with their time, patience and kindness. Everyone in SOCSI has made the experience of doing a doctorate a pleasurable one. Thanks to Dr. Tom Hall and Dr. Ian Welsh for their input along the way. None of this would have been possible without a grant from the Economic and Social Research Council. -

Capturing-Sound-How-Technology-Has-Changed-Music.Pdf

ROTH FAMILY FOUNDATION Music in America Imprint Michael P. Roth and Sukey Garcetti have endowed this imprint to honor the memory of their parents, Julia and Harry Roth, whose deep love of music they wish to share with others. This publication has been supported by a subvention from the Gustave Reese Publication Endowment Fund of the American Musicological Society. The publisher gratefully acknowledges the generous contribution to this book provided by the Music in America Endowment Fund of the University of California Press Associates, which is supported by a major gift from Sukey and Gil Garcetti, Michael Roth, and the Roth Family Foundation. CAPTURING SOUND H O W CAPT T U E C R H N I O N L O G G Y S UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS H A S O C H U A N N G E D D M BERKELEY LOS ANGELES LONDON U S I C tz mark ka University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England “The Entertainer” written by Billy Joel © 1974, JoelSongs [ASCAP]. All rights reserved. Used by permission. © 2004 by the Regents of the University of California Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Katz, Mark, 1970–. Capturing sound : how technology has changed music / Mark Katz. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-520-24196-7 (cloth : alk. paper)— ISBN 0-520-24380-3 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Sound recording industry. 2. Music and technology. I. Title. ml3790.k277 2005 781.49—dc22 2004011383 Manufactured in the United States of America 13 12 11 10 09 08 07 06 05 04 10987654 321 The paper used in this publication is both acid-free and totally chlorine-free (TCF). -

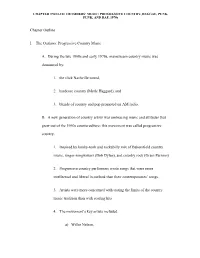

Chapter Outline

CHAPTER TWELVE: OUTSIDERS’ MUSIC: PROGRESSIVE COUNTRY, REGGAE, PUNK, FUNK, AND RAP, 1970s Chapter Outline I. The Outlaws: Progressive Country Music A. During the late 1960s and early 1970s, mainstream country music was dominated by: 1. the slick Nashville sound, 2. hardcore country (Merle Haggard), and 3. blends of country and pop promoted on AM radio. B. A new generation of country artists was embracing music and attitudes that grew out of the 1960s counterculture; this movement was called progressive country. 1. Inspired by honky-tonk and rockabilly mix of Bakersfield country music, singer-songwriters (Bob Dylan), and country rock (Gram Parsons) 2. Progressive country performers wrote songs that were more intellectual and liberal in outlook than their contemporaries’ songs. 3. Artists were more concerned with testing the limits of the country music tradition than with scoring hits. 4. The movement’s key artists included a) Willie Nelson, CHAPTER TWELVE: OUTSIDERS’ MUSIC: PROGRESSIVE COUNTRY, REGGAE, PUNK, FUNK, AND RAP, 1970s b) Kris Kristopherson, c) Tom T. Hall, and d) Townes Van Zandt. 5. These artists were not polished singers by conventional standards, but they wrote distinctive, individualist songs and had compelling voices. 6. They developed a cult following, and progressive country began to inch its way into the mainstream (usually in the form of cover versions). a) “Harper Valley PTA” (1) Original by Tom T. Hall (2) Cover version by Jeannie C. Riley; Number One pop and country (1968) b) “Help Me Make It through the Night” (1) Original by Kris Kristofferson (2) Cover version by Sammi Smith (1971) C. Willie Nelson 1. -

Juvenile RUF Combatants and the Role of Music in the Sierra Leone Civil War

“We Listened to it Because of the Message”: Juvenile RUF Combatants and the Role of Music in the Sierra Leone Civil War CORNELIA NUXOLL Introduction This article will explore the role of music in the Sierra Leonean conflict and the extent to which music facilitated the construction of identities and the formation of social cohesion within the Revolutionary United Front (henceforth RUF) rebel movement.1 Moreover, it will look at the RUF’s use of music as an instrument of terror in this war. First, I will briefly outline the dynamics that gave rise to the war, and then I will look into reasons for the widespread juvenile participation, touching on diverse motives and the heterogeneous composition of members within the RUF revolution. With regard to the juvenile combatants in this conflict, I will focus on how they utilized music in different ways, for different reasons and various ends. Background From 1991 until 2002 a civil war raged in the West African country of Sierra Leone. After decades of increasing state decline due to the personal rule of one-party politics, bad governance, nepotism, political corruption, and economic failure, the RUF invaded Sierra Leone, claiming to overthrow the then ruling All People’s Congress (APC) government with support from Charles Taylor’s Liberian special forces, rebel combatants of the National Patriotic Front of Liberia (NPFL). The mismanagement of the APC government had left Sierra Leoneans in a state of abject poverty with no proper access to democratic participation in decision-making processes or to political representation. The failures in governance and the deterioration of institutional processes led to the weakening of the state’s capacity to ensure the security and livelihood of its citizens, thus creating the conditions for a collapsing state.