Light Music in the Practice of Australian Composers in the Postwar Period, C.1945-1980

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adelaide Radio

EMBARGOED UNTIL 9:30AM (AEDT) ADELAIDE RADIO - SURVEY 8 2019 Share Movement (%) by Demographic, Mon-Sun 5.30am-12midnight People 10+ People 10-17 People 18-24 People 25-39 People 40-54 People 55-64 People 65+ Station This Last +/- This Last +/- This Last +/- This Last +/- This Last +/- This Last +/- This Last +/- FIVEaa 10.9 10.3 0.6 2.0 2.1 -0.1 0.7 0.8 -0.1 2.4 4.4 -2.0 6.6 6.5 0.1 8.5 9.9 -1.4 27.6 22.9 4.7 CRUISE1323 9.6 9.4 0.2 1.9 3.3 -1.4 4.2 0.5 3.7 1.3 2.0 -0.7 5.9 4.7 1.2 16.7 17.5 -0.8 17.9 18.3 -0.4 MIX102.3 13.6 11.9 1.7 19.5 19.1 0.4 17.5 13.6 3.9 10.7 8.9 1.8 17.2 16.3 0.9 19.9 15.0 4.9 5.5 5.9 -0.4 5MMM 8.6 9.7 -1.1 8.2 8.0 0.2 9.0 8.0 1.0 11.8 10.5 1.3 12.1 16.1 -4.0 8.5 10.9 -2.4 3.1 3.5 -0.4 NOVA91.9 11.0 12.0 -1.0 25.9 28.5 -2.6 20.8 32.1 -11.3 19.6 18.2 1.4 12.5 12.6 -0.1 4.7 5.6 -0.9 0.8 0.9 -0.1 HIT 107 9.3 9.6 -0.3 18.0 16.7 1.3 16.5 15.9 0.6 19.3 20.4 -1.1 9.0 10.5 -1.5 5.5 4.6 0.9 0.6 0.2 0.4 ABC ADE 9.0 10.0 -1.0 1.6 1.9 -0.3 0.7 0.8 -0.1 1.3 2.0 -0.7 4.9 3.5 1.4 12.2 14.4 -2.2 20.6 23.6 -3.0 5RN 2.1 1.9 0.2 0.2 * * 0.3 * * 0.3 0.1 0.2 1.0 0.9 0.1 3.6 1.5 2.1 4.3 5.4 -1.1 ABC NEWS 1.4 1.2 0.2 0.6 0.3 0.3 0.5 1.1 -0.6 0.7 0.6 0.1 2.4 1.9 0.5 1.2 1.3 -0.1 1.7 1.4 0.3 5JJJ 5.9 5.4 0.5 7.9 7.4 0.5 12.1 12.6 -0.5 11.4 7.8 3.6 8.2 8.6 -0.4 1.7 2.2 -0.5 0.3 0.4 -0.1 ABC CLASSIC 2.9 3.4 -0.5 1.1 0.8 0.3 0.3 0.1 0.2 2.0 2.1 -0.1 2.1 1.3 0.8 1.5 1.5 0.0 6.5 9.1 -2.6 Share Movement (%) by Session, P10+ Mon-Fri Breakfast Morning Afternoon Drive Evening Weekend Station Mon-Fri 5:30am-12mn Mon-Fri 5:30am-9:00am Mon-Fri 9:00am-12:00md -

ANNUAL REPORT 2019 Revellers at New Year’S Eve 2018 – the Night Is Yours

AUSTRALIAN BROADCASTING CORPORATION ANNUAL REPORT 2019 Revellers at New Year’s Eve 2018 – The Night is Yours. Image: Jared Leibowtiz Cover: Dianne Appleby, Yawuru Cultural Leader, and her grandson Zeke 11 September 2019 The Hon Paul Fletcher MP Minister for Communications, Cyber Safety and the Arts Parliament House Canberra ACT 2600 Dear Minister The Board of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation is pleased to present its Annual Report for the year ended 30 June 2019. The report was prepared for section 46 of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013, in accordance with the requirements of that Act and the Australian Broadcasting Corporation Act 1983. It was approved by the Board on 11 September 2019 and provides a comprehensive review of the ABC’s performance and delivery in line with its Charter remit. The ABC continues to be the home and source of Australian stories, told across the nation and to the world. The Corporation’s commitment to innovation in both storytelling and broadcast delivery is stronger than ever, as the needs of its audiences rapidly evolve in line with technological change. Australians expect an independent, accessible public broadcasting service which produces quality drama, comedy and specialist content, entertaining and educational children’s programming, stories of local lives and issues, and news and current affairs coverage that holds power to account and contributes to a healthy democratic process. The ABC is proud to provide such a service. The ABC is truly Yours. Sincerely, Ita Buttrose AC OBE Chair Letter to the Minister iii ABC Radio Melbourne Drive presenter Raf Epstein. -

18 May 1999 Professor Richard Snape Commissioner Productivity

18 May 1999 Professor Richard Snape Commissioner Productivity Commission Locked Bag 2 Collins Street East Post Office MELBOURNE VIC 8003 Dear Professor Snape I attach the ABC’s submission to the Productivity Commission’s review of the Broadcasting Services Act. I look forward to discussing the issues raised at the public hearing called in Melbourne on 7 June, and in the meantime I would be happy to elaborate on any matter covered in our submission. The ABC is preparing a supporting submission focusing on the economic and market impacts of public broadcasting, and this will be made available to the Commission at the beginning of June. Yours sincerely, BRIAN JOHNS Managing Director AUSTRALIAN BROADCASTING CORPORATION SUBMISSION TO THE PRODUCTIVITY COMMISSION REVIEW OF THE BROADCASTING SERVICES ACT 1992 MAY 1999 CONTENTS Introduction 4 1. The ABC’s obligations under its own Act 6 1.1 The ABC’s Charter obligations 6 1.2 ABC’s range of services 7 1.3 Public perception of the ABC 7 2. The ABC and the broadcasting industry 9 2.1 ABC’s role in broadcasting: the difference 9 2.2 ABC as part of a diverse industry 14 2.3 ABC’s role in broadcasting: the connections 15 3. Regulation of competition in the broadcasting industry 16 3.1 Aim of competition policy/control rules 16 3.2 ABC and competition policy 17 3.3 ABC as program purchaser 17 3.4 ABC as program seller 17 3.5 BSA control rules and diversity 18 3.6 ACCC as regulator 19 4. Relationship with other regulators 20 4.1 Australian Broadcasting Authority 20 4.2 Australian Communications Authority (ACA) 21 5. -

Execulive Turnlable Insidetrack

66 Lote General News MERCER ELLINGTON BOOKED $25,000 Grant To Ensure InsideTrack George Wein still hopes to open an innovative jazz then went on sale. The entertainers appeared before an Duke's Music At Newport showcase in New York similar to his successful Boston estimated 62,000 persons -most of them getting their Storyville jazz club of the 1950s, but the planned Feb. 28 first taste of country music. NEW YORK -Audiences at this George Wein has been able to sal- bow may be delayed. As a place where musicians could AI Bramy, San Francisco distribution pioneer, is con- year's Newport Jazz Festival will be vage at least some of the concerts for meet, jam and try out new ideas, it was to be housed in valescing at his home from a minor heart attack. He will treated to a series of concerts cov- Newport with relative ease. the basement of Frank's Place on East 48th St. in Man- return to Eric Mainland as general manager in about ering the early works of the late The first of the four concerts will hattan. four weeks. Duke Ellington, thanks to a $25,000 cover Ellington's music during the At midpoint of Bette Midler's four -month national W.F. "Jim" Myers, SESAC vice president and di- grant from the National Endowment 1920s, and the second and third will tour, gross is reported as topping $1.2 million, including rector of international relations, returns to the U.S. the for the Arts. follow his growth and style through a record $403,000 for six days at Los Angeles' Chandler end of the month following visits to Paris, Helsinki, The concerts were originally the 1930s and 1940s. -

Eva Dahlgren 4 Vast Resource of Information Not Likely Found in Much of Gay Covers for Sale 6 Mainstream Media

Lambda Philatelic Journal PUBLICATION OF THE GAY AND LESBIAN HISTORY ON STAMPS CLUB DECEMBER 2004, VOL. 23, NO. 4, ISSN 1541-101X Best Wishes French souvenir sheet issued to celebrate the new year. December 2004, Vol. 23, No. 4 The Lambda Philatelic Journal (ISSN 1541-101X) is published MEMBERSHIP: quarterly by the Gay and Lesbian History on Stamps Club (GLHSC). GLHSC is a study unit of the American Topical As- Yearly dues in the United States, Canada and Mexico are sociation (ATA), Number 458; an affiliate of the American Phila- $10.00. For all other countries, the dues are $15.00. All telic Society (APS), Number 205; and a member of the American checks should be made payable to GLHSC. First Day Cover Society (AFDCS), Number 72. Single issues $3. The objectives of GLHSC are to promote an interest in the col- There are two levels of membership: lection, study and dissemination of knowledge of worldwide philatelic material that depicts: 1) Supportive, your name will not be released to APS, ATA or AFDCS, and 6 Notable men and women and their contributions to society 2) Active, your name will be released to APS, ATA and for whom historical evidence exists of homosexual or bisex- AFDCS (as required). ual orientation, Dues include four issues of the Lambda Philatelic Journal and 6 Mythology, historical events and ideas significant in the his- a copy of the membership directory. (Names will be with- tory of gay culture, held from the directory upon request.) 6 Flora and fauna scientifically proven to having prominent homosexual behavior, and ADVERTISING RATES: 6 Even though emphasis is placed on the above aspects of stamp collecting, GLHSC strongly encourages other phila- Members are entitled to free ads. -

Models of Time Travel

MODELS OF TIME TRAVEL A COMPARATIVE STUDY USING FILMS Guy Roland Micklethwait A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University July 2012 National Centre for the Public Awareness of Science ANU College of Physical and Mathematical Sciences APPENDIX I: FILMS REVIEWED Each of the following film reviews has been reduced to two pages. The first page of each of each review is objective; it includes factual information about the film and a synopsis not of the plot, but of how temporal phenomena were treated in the plot. The second page of the review is subjective; it includes the genre where I placed the film, my general comments and then a brief discussion about which model of time I felt was being used and why. It finishes with a diagrammatic representation of the timeline used in the film. Note that if a film has only one diagram, it is because the different journeys are using the same model of time in the same way. Sometimes several journeys are made. The present moment on any timeline is always taken at the start point of the first time travel journey, which is placed at the origin of the graph. The blue lines with arrows show where the time traveller’s trip began and ended. They can also be used to show how information is transmitted from one point on the timeline to another. When choosing a model of time for a particular film, I am not looking at what happened in the plot, but rather the type of timeline used in the film to describe the possible outcomes, as opposed to what happened. -

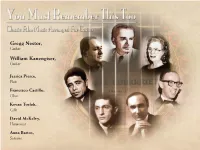

Gregg Nestor, William Kanengiser

Gregg Nestor, Guitar William Kanengiser, Guitar Jessica Pierce, Flute Francisco Castillo, Oboe Kevan Torfeh, Cello David McKelvy, Harmonica Anna Bartos, Soprano Executive Album Producers for BSX Records: Ford A. Thaxton and Mark Banning Album Produced by Gregg Nestor Guitar Arrangements by Gregg Nestor Tracks 1-5 and 12-16 Recorded at Penguin Recording, Eagle Rock, CA Engineer: John Strother Tracks 6-11 Recorded at Villa di Fontani, Lake View Terrace, CA Engineers: Jonathan Marcus, Benjamin Maas Digitally Edited and Mastered by Jonathan Marcus, Orpharian Recordings Album Art Direction: Mark Banning Mr. Nestor’s Guitars by Martin Fleeson, 1981 José Ramirez, 1984 & Sérgio Abreu, 1993 Mr. Kanengiser’s Guitar by Miguel Rodriguez, 1977 Special Thanks to the composer’s estates for access to the original scores for this project. BSX Records wishes to thank Gregg Nestor, Jon Burlingame, Mike Joffe and Frank K. DeWald for his invaluable contribution and oversight to the accuracy of the CD booklet. For Ilaine Pollack well-tempered instrument - cannot be tuned for all keys assuredness of its melody foreshadow the seriousness simultaneously, each key change was recorded by the with which this “concert composer” would approach duo sectionally, then combined. Virtuosic glissando and film. pizzicato effects complement Gold's main theme, a jaunty, kaleidoscopic waltz whose suggestion of a Like Korngold, Miklós Rózsa found inspiration in later merry-go-round is purely intentional. years by uniting both sides of his “Double Life” – the title of his autobiography – in a concert work inspired by his The fanfare-like opening of Alfred Newman’s ALL film music. Just as Korngold had incorporated themes ABOUT EVE (1950), adapted from the main title, pulls us from Warner Bros. -

Annual Financial Report 30 June 2020

Australasian Performing Right Association Limited (a company limited by guarantee) and its controlled entity ABN 42 000 016 099 Annual Financial Report 30 June 2020 Australasian Performing Right Association Limited and its controlled entity Annual Report 30 June 2020 Directors’ report For the year ended 30 June 2020 The Directors present their report together with the financial statements of the consolidated entity, being the Australasian Performing Right Association Limited (Company) and its controlled entity, for the financial year ended 30 June and the independent auditor’s report thereon. Directors The Directors of the Company at any time during or since the financial year are: Jenny Morris OAM, MNZM Non-executive Writer Director since 1995 and Chair of the Board A writer member of APRA since 1983, Jenny has been a music writer, performer and recording artist since 1980 with three top 5 and four top 20 singles in Australia and similar success in New Zealand. Jenny has recorded nine albums gaining gold, platinum and multi-platinum status in the process and won back to back ARIA awards for best female vocalist. Jenny was inducted into the NZ Music Hall of Fame in 2018. Jenny is also a non-executive director and passionate supporter of Nordoff Robbins Music Therapy Australia. Jenny presents their biennial ‘Art of Music’ gala event, which raises significant and much needed funds for the charity. Bob Aird Non-executive Publisher Director from 1989 to 2019 Bob recently retired from his position as Managing Director of Universal Music Publishing Pty Limited, Universal Music Publishing Group Pty Ltd, Universal/MCA Publishing Pty Limited, Essex Music of Australia Pty Limited and Cromwell Music of Australia Pty Limited which he held for 16 years. -

The Dilemma of Aural Skills Within Year Eleven Music

THE DILEMMA OF AURAL SKILLS WITHIN YEAR ELEVEN MUSIC PROGRAMMES IN THE NEW ZEALAND CURRICULUM Thesis submitted in partial FulFilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master in Teaching and Learning In the University oF Canterbury By Robert J. Aburn University of Canterbury 2015 Table of Contents Table of Contents ................................................................................................................. ii List of Figures ....................................................................................................................... v List of Tables ......................................................................................................................... v Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................. vi List of Terms and Abbreviations ......................................................................................... viii Abstract ................................................................................................................................. i Chapter 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................ 1 1:1 Introduction: ................................................................................................................................................................... 1 1:2 Research Question ...................................................................................................................................................... -

Lister); an American Folk Rhapsody Deutschmeister Kapelle/JULIUS HERRMANN; Band of the Welsh Guards/Cap

Guild GmbH Guild -Light Catalogue Bärenholzstrasse 8, 8537 Nussbaumen, Switzerland Tel: +41 52 742 85 00 - e-mail: [email protected] CD-No. Title Track/Composer Artists GLCD 5101 An Introduction Gateway To The West (Farnon); Going For A Ride (Torch); With A Song In My Heart QUEEN'S HALL LIGHT ORCHESTRA/ROBERT FARNON; SIDNEY TORCH AND (Rodgers, Hart); Heykens' Serenade (Heykens, arr. Goodwin); Martinique (Warren); HIS ORCHESTRA; ANDRE KOSTELANETZ & HIS ORCHESTRA; RON GOODWIN Skyscraper Fantasy (Phillips); Dance Of The Spanish Onion (Rose); Out Of This & HIS ORCHESTRA; RAY MARTIN & HIS ORCHESTRA; CHARLES WILLIAMS & World - theme from the film (Arlen, Mercer); Paris To Piccadilly (Busby, Hurran); HIS CONCERT ORCHESTRA; DAVID ROSE & HIS ORCHESTRA; MANTOVANI & Festive Days (Ancliffe); Ha'penny Breeze - theme from the film (Green); Tropical HIS ORCHESTRA; L'ORCHESTRE DEVEREAUX/GEORGES DEVEREAUX; (Gould); Puffin' Billy (White); First Rhapsody (Melachrino); Fantasie Impromptu in C LONDON PROMENADE ORCHESTRA/ WALTER COLLINS; PHILIP GREEN & HIS Sharp Minor (Chopin, arr. Farnon); London Bridge March (Coates); Mock Turtles ORCHESTRA; MORTON GOULD & HIS ORCHESTRA; DANISH STATE RADIO (Morley); To A Wild Rose (MacDowell, arr. Peter Yorke); Plink, Plank, Plunk! ORCHESTRA/HUBERT CLIFFORD; MELACHRINO ORCHESTRA/GEORGE (Anderson); Jamaican Rhumba (Benjamin, arr. Percy Faith); Vision in Velvet MELACHRINO; KINGSWAY SO/CAMARATA; NEW LIGHT SYMPHONY (Duncan); Grand Canyon (van der Linden); Dancing Princess (Hart, Layman, arr. ORCHESTRA/JOSEPH LEWIS; QUEEN'S HALL LIGHT ORCHESTRA/ROBERT Young); Dainty Lady (Peter); Bandstand ('Frescoes' Suite) (Haydn Wood) FARNON; PETER YORKE & HIS CONCERT ORCHESTRA; LEROY ANDERSON & HIS 'POPS' CONCERT ORCHESTRA; PERCY FAITH & HIS ORCHESTRA; NEW CONCERT ORCHESTRA/JACK LEON; DOLF VAN DER LINDEN & HIS METROPOLE ORCHESTRA; FRANK CHACKSFIELD & HIS ORCHESTRA; REGINALD KING & HIS LIGHT ORCHESTRA; NEW CONCERT ORCHESTRA/SERGE KRISH GLCD 5102 1940's Music In The Air (Lloyd, arr. -

Indigenous Encounters in Australian Symphonies of the 1950S

Symphonies of the bush: indigenous encounters in Australian symphonies1 Rhoderick McNeill Dr Rhoderick McNeill is Senior Lecturer in Music History and Music Theory at the University of Southern Queensland, Toowoomba. His principal research interest lies in Australian symphonic music of the earlier 20th century, with particular study of Australian symphonies of the 1950s. Between 1985 and 1995 he helped establish the Faculty of Performing Arts at Nommensen University in Medan, Indonesia. Dr McNeill’s two volume Indonesian-language textbook on Music History was published in Jakarta in 1998 and has been reprinted twice. Landscape was a powerful stimulus to many composers working within extended tonal, nationalist idioms in the early 20th century. Sibelius demonstrated this trend in connection with Finland, its landscape, literature, history and myths. Similar cases can be made for British composers like Elgar, Vaughan Williams, Bax and Moeran, and for American composers Copland and Harris. All these composers wrote symphonies and tone poems, and were important figures in the revival of these forms during the 1920s and 30s. Their music formed much of the core of „modern‟ repertoire heard in Australian orchestral concerts prior to 1950. It seemed logical for some Australian composers -by no means all - to seek a home-grown style which would parallel national styles already forged in Finland, Britain and the United States. They believed that depicting the „timeless‟ Australian landscape in their music would introduce this new national style; their feelings on this issue are clearly outlined in the prefaces to their scores or in their writings or by giving their works evocative Australian titles. -

Files/2014 Women and the Big Picture Report.Pdf>, Accessed 6 September 2018

The neuroscientific uncanny: a filmic investigation of twenty-first century hauntology GENT, Susannah <http://orcid.org/0000-0003-0091-2555> Available from the Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/26099/ A Sheffield Hallam University thesis This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Please visit http://shura.shu.ac.uk/26099/ and http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html for further details about copyright and re-use permissions. THE NEUROSCIENTIFIC UNCANNY: A FILMIC INVESTIGATION OF TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY HAUNTOLOGY Susannah Gent A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Sheffield Hallam University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy October 2019 Candidate Declaration I hereby declare that: 1. I have not been enrolled for another award of the University, or other academic or professional organisation, whilst undertaking my research degree. 2. None of the material contained in the thesis has been used in any other submission for an academic award. 3. I am aware of and understand the University’s policy on plagiarism and certify that this thesis is my own work. The use of all published or other sources of material consulted have been properly and fully acknowledged. 4. The work undertaken towards the thesis has been conducted in accordance with the SHU Principles of Integrity in Research and the SHU Research Ethics Policy.