Genealogy the Mediation of the Witness to History As a Carrier of Memory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In 1945 World War Two Was Coming to an End and to the Misfortune of the Nazi's the Allies Were Winning the Battle

In 1945 World War Two was coming to an end and to the misfortune of the Nazi's the Allies were winning the battle. The Russians were fast invading into Berlin and because of the deteriorating situation of the Nazi's defeat was imminent. Hitler retreated into his private bunker where he faced the difficult choice; admit defeat and surrender to the Russians where he will pay for his crimes, or suicide. There is a conspiracy theory claiming that the authenticity of Hitler’s suicide was a lie and [1] the truth was that he escaped in a ghost convoy to Argentina where he lived out the rest of his life. So the famous story goes that Hitler shot himself and also bit into a cyanide capsule. [4] This story was rejected by the public and the most popular theory that was widely believed on the death of Hitler was his escape to Argentina. This was more well believed because of the lack of evidence against the theory, in fact there was evidence pointing towards it. The witnesses to the account of Hitler being alive after his 'suicide' had a stronger validity compared to a dodgy story given by Rochus Misch. The story goes that Hitler faked his death in the bunker to cover any evidence that he was still alive and with the aid of high ranking officers, he moved around a few european countries first before finally landing in Argentina. Abel Basti is a famous author/historian who wrote the book "Hitler in Argentina" which was based on the theory. -

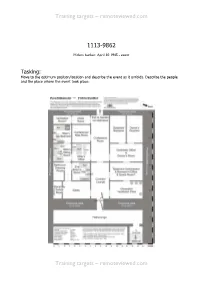

Remoteviewed.Com 1113-9862

Training targets – remoteviewed.com 1113-9862 Hitlers bunker, April 30 1945 - event Tasking: Move to the optimum position/location and describe the event as it unfolds. Describe the people and the place where the event took place. Training targets – remoteviewed.com Training targets – remoteviewed.com Additional feedback: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hitler%27s_bunker The Führerbunker (or "Fuehrerbunker") is a common name for a complex of subterranean rooms in Berlin, Germany where Adolf Hitler committed suicide during World War II. The bunker was the 13th and last of Hitler's Führerhauptquartiere or Fuehrer Headquarters (another was the famous Wolfsschanze). There were actually two bunkers which were connected - the older Vorbunker and the newer Führerbunker. The Führerbunker was located about 17 meters beneath the garden of the Reichskanzlei (Reich Chancellory), approx. 120 meters north of the new Reichskanzlei building, which had the address Vossstrasse 6. The Vorbunker was located beneath the large hall behind the old Reichskanzlei, which was connected to the new Reichskanzlei. The old kanzlei was located along Wilhelmstrasse, and had probably the address Wilhelmstrasse 77. The Führerbunker was located somewhat lower than the Vorbunker and west (or rather west-west-south) of it. The map opposite shows the approximate locations of the two bunkers. The two bunkers were connected via sets of stairs set at right angles (not spiral as some believe). The complex was protected by approximately 3 m of concrete, and about 30, rather small, rooms were distributed over two levels with exits into the main buildings and an emergency exit into the gardens. The complex was built in two distinct phases, one part in 1936 and the other in 1943. -

Comparing Hitler and Stalin: Certain Cultural Considerations

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 6-2014 Comparing Hitler and Stalin: Certain Cultural Considerations Phillip W. Weiss Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/303 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Comparing Hitler and Stalin: Certain Cultural Considerations by Phillip W. Weiss A master’s thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, The City University of New York 2014 ii Copyright © 2014 Phillip W. Weiss All Rights Reserved iii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Master of Arts. (typed name) David M. Gordon __________________________________________________ (required signature) __________________________ __________________________________________________ Date Thesis Advisor (typed name) Matthew K. Gold __________________________________________________ (required signature) __________________________ __________________________________________________ Date Executive Officer THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iv Acknowledgment I want to thank Professor David M. Gordon for agreeing to become my thesis advisor. His guidance and support were major factors in enabling me to achieve the goal of producing an interesting and informative scholarly work. As my mentor and project facilitator, he provided the feedback that kept me on the right track so as to ensure the successful completion of this project. -

Selling Hitler Tells the Story of the Biggest Fraud in Publishing History

CONTENTS About the Book About the Author Also by Robert Harris Title Page Acknowledgements List of illustrations Dramatis Personae Prologue Part One Chapter One Chapter Two Chapter Three Part Two Chapter Four Chapter Five Chapter Six Chapter Seven Chapter Eight Chapter Nine Chapter Ten Part Three Chapter Eleven Chapter Twelve Chapter Thirteen Chapter Fourteen Chapter Fifteen Chapter Sixteen 1 Chapter Seventeen Chapter Eighteen Chapter Nineteen Chapter Twenty Chapter Twenty-One Chapter Twenty-Two Chapter Twenty-Three Chapter Twenty-Four Part Four Chapter Twenty-Five Chapter Twenty-Six Chapter Twenty-Seven Chapter Twenty-Eight Chapter Twenty-Nine Chapter Thirty Epilogue Picture Section Index Copyright 2 About the Book APRIL 1945: From the ruins of Berlin, a Luftwaffe transport plane takes off carrying secret papers belonging to Adolf Hitler. Half an hour later, it crashes in flames . APRIL 1983: In a bank vault in Switzerland, a German magazine offers to sell more than 50 volumes of Hitler’s secret diaries. The asking price is $4 million . Written with the pace and verve of a thriller and hailed on publication as a classic, Selling Hitler tells the story of the biggest fraud in publishing history. 3 About the Author Robert Harris is the author of Fatherland, Enigma, Archangel, Pompeii, Imperium and The Ghost, all of which were international bestsellers. His latest novel, Lustrum, has just been published. His work has been translated into thirty-seven languages. After graduating with a degree in English from Cambridge University, he worked as a reporter for the BBC’s Panorama and Newsnight programmes, before becoming political editor of the Observer and subsequently a columnist on the Sunday Times and the Daily Telegraph. -

USHMM Finding

http://collections.ushmm.org Contact [email protected] for further information about this collection 01/28/2004 MISCH, Rochus Germany Documentation Project German RG-50.486*0028 In diesem Interview spricht Rochus Misch über sein Leben in Adolf Hitlers Begleitkommando und als Hitlers Telefonist, Kurier und Leibwächter. Er spricht darüber, wie er diesem inneren Kreis beitrat, und welche Tätigkeiten er in seinen verschiedenen Funktionen ausübte. Darüber hinaus erzählt Misch von seiner 9-jährigen Kriegsgefangenschaft in Russland, und spricht kurz über seine Rückkehr nach Berlin und seine derzeitigen Familienverhältnisse. Band 1 [01:] 01:00:15 – [01:] 07:00:20 Die Interviewerin bittet ihn, über seine Kindheit zu sprechen; er heißt Rochus Misch, geboren am 29. Juli 1917; seine Heimatstadt ist Alt-Schalkendorf (Alt-Schalkovitz), nahe Oppeln (Opole); sein Bruder und er sind Waisenkinder; sein Bruder ist in jungen Jahren tödlich verunglückt; die Eltern: Rochus und Victoria; Vater und Großvater sind Bauarbeiter; nach achtjähriger Schulzeit drängt ihn sein Großvater, einen Handwerksberuf zu erlernen; seine Cousine Marie aus Hoyerswerda vermittelt ihm 1932, durch Verbindungen ihres Ehemannes, eine Lehrstelle bei der Firma Schüller und Model; 1935 wird er mit der Anfertigung zweier Gemälde betraut; diese sollen bei den Olympischen Sommerspielen 1936 als Preise vergeben werden; durch diesen Auftrag verdient er beinahe 500 Reichsmark; dies ermöglicht ihm, sich ein 6-monatiges Studium an der Kölner Meisterschule für Bildende Künste zu finanzieren. [01:] 07:00:21 – [01:] 14:07:25 Die Interviewerin fragt ihn nach seinen Erinnerungen an die 1920er- und 1930er-Jahre; ob er Mitglied in einer Jugendorganisation war; sie fragt, ob die Ernennung Hitlers zum Reichskanzler in seiner Stadt jemanden interessiert habe; er sagt, dass er zu jener Zeit sehr alleine war und arbeiten musste; er interessierte sich für seinen Beruf und für Sport; einmal spielte er eine Rolle in einem Theaterstück; 1933 weiß er nichts von Hitler; am 1. -

MUELLER, HEINRICH VOL. 2 0026.Pdf

SENDE,-; - ...Hat..... CLASS .rioN TOP ps!" ,spni CONFIDENT/A L 1 SECRET 1 UNCL!-,SSIFIED — OFFICIAL ROUTING SLIP ---- TO NAME AND ADDRESS DATE INITIALS 1 IP/Analysls -;c:‘, . 2 3 4 . 5 ' • ACT ON DIRECT REPLY PREPARE REPLY APPROVAL DISPATCH RECOMMENDATION COMMENT FILE RETURN - CONCURRENCE - - -- INFORMATION - SIGNATURE Remarks: . One copy of this should go into the 201 file of Heinrich Mueller, born 28 April, 1900. k The name s beginning page 5 should be indexed to this file.. , _ Thanks, ---- ' - FOLD HERE TO RETURN TO SENDER FROM: NAME. ADDRESS AND FrE N . DATE f"4cr-72.:•-1,,„-,M-4- , ■ • .z,- , = / .A CI PIR,C0 t , ..• IIMEICEIZIMWIA S CR ET FORM NO. Use previous editi dRir (40) 1-67-67 Z. DECLASSIFIED AND REL CEMTRA_L EASED BY - IIIIELLISENCE AG SOURPES METHODS EXEMPT ENCY IO NAZI WAR CR N3B2B IMES DISCLOSURE ACT DA1E 2000 2006 Sp: e )1 Foreign Discern • DIRECTORATE OF PLANS Counterintelligence Briefs C The Hunt for "Gestapo Mueller' _CSCl/316/03035-7 December 1971 Copy _No 3 74L2 76 n y WARNING This document contains information affecting the national defense of the United States, within the meaning of Title 18, sections 793 and 794, of the US Code, as amended. Its transmission or revelation of its contents to or re- ceipt by an unauthorized person is prohibited by law. GROUP 1 Excludod from amok IIIQ ond ossification `J • • I 41. • b!, .., .APAiTi; 4M0441;1041 ,!4411pAte4ssIt.,,,,,,,q,ne" ,4,64.ct9LJImlvflo;%p/00.41fAf,,,, rmz..4w;Y.; t is`4% :4 ObbA1104g$144W 14..*V9, • ET NO REIGN DISSEM CENTRAL INTELLIGENCE AGENCY Directorate of Plans October 1971 COUNTERINTELLIGENCE BRIEF THE HUNT FOR "GESTAPO MUELLER" Counterintelligence Briefs analyse significant espionage and counterespionage cases in the context of other clandestine and political events affecting -- and affected by -- these cases. -

Translation of Transcription in German of Testimony by Rochus MISCH on January 28, 2004

http://collections.ushmm.org Contact [email protected] for further information about this collection RG-50.486.0028 Rochus MISCH Translation of Transcription in German of Testimony by Rochus MISCH on January 28, 2004 Translation made by Ed Swecker, February 2006 Tape 1 Q: May I just ask you to give your name? A: My name? First and last name? Q: Yes, first and last name. A: My name is Rochus, first name, Misch Q: And when were you born? A: I was born in July 1917, in the middle of the war. Q: What day in July? A: On 29 July 1917. Q: And where? A. In Altschalkendorf…known then as Altschalkowitz; that is in the vicinity of Oppeln. Q: Were your parents from there or somewhere else? A: No. My parents…my father had been seriously wounded during the war and he was in a local hospital in Oppeln. And he was given a furlough from there for a few days which my mother had not expected…she was at the end of her pregnancy. And that was on the 24th. And on the 26th he suffered a hemorrhage…and my father died. In the village there was no doctor and naturally that was a very difficult time for my mother, you know. And on the third day the men came in order to….in order to fetch the coffin with my dead father. And my mother had seen that, from the window when they carried him on their shoulders, my father and that caused her to scream terribly. -

De Siste Dager Sno

Stiftelsen norsk Okkupasjonshistorie BUN- KE- REN;D" <e rUS86t"ttt: inntok b-un- keren V(lT alt stille. In· gen var t~l· bake. Hitler og ha~'8 nærmeste medarbet,.. j dere hadde }~ alle tatt.,-iII eget liv. .~ DE SISTE DAGER SNO +~9J,,"~ lIQ!l~~. ~~Ilti~~~~~tl.:rQ~ ~.~~f'CJ.AARD . -.:, .' ':..' .'.':. .' "'.' : .;:',~ '\ .'..:,",.'! i:t· l:: ~·i:'" . ,~'. ""... ', ", .. ,' ..' ."," i.·: ,.j.: ~ ' . ----------- Stiftelsen norsk Okkupasjonshistorie - Jeg var pa vei over i Kan!jcllict for å spbe. Jeg ble llwgct l'edd og DE SISTE DAGER gikk videre, men snudde så og løp tilbake med bankende hjerte. Da sil jeg at Linge, adjutant GUnehe og en til svøpte «der Chef" inn i et ullteppe og bar ham opp trappa. Han var I HITLERS skutt I tinningen. - Eva Braun satt i sofaen med be na trukkel opp under seg. Hun så ut som hun HOV. Det var forferdelig BUNKER men også en lettelse. Nå visste vi at Forts. fra forrige side alt omsider var over, sier Mlsch. Han diskuterte med en soldatkaM ',:'·husly. Mor og barn i den øvre bunke merat hva de nå skulle gjøre. Kame· : ren, propagandaministeren selv i raten valgte å stikke av, Misch gikk ';': d.en nedre. tilbake til vaktrommet sitt. ,Omringet av russerne Forgiftet sine egne barn Over bakken var Berlin nå Olnrin Da han begynte sin vakt kl. 14.00 1. get på tre kanter av russerne. Dagen mai, lekte de seks Goebbels-barna l etter sin fødselsdag hadde Hitler gitt den nedre bunkeren. Misch ga deln SS-general Steiner ordre om moian- brus og spilte litt ball med dem. Se· " grep. -

Adolf Hitler from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Create account Log in Article Talk Read View source View history Adolf Hitler From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia "Hitler" redirects here. For other uses, see Hitler (disambiguation). Navigation Adolf Hitler (German: [ˈadɔlf ˈhɪtlɐ] ( listen); 20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born Main page Adolf Hitler German politician and the leader of the Nazi Party (German: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Contents Arbeiterpartei (NSDAP); National Socialist German Workers Party). He was chancellor of Featured content Germany from 1933 to 1945 and dictator of Nazi Germany (as Führer und Reichskanzler) from Current events 1934 to 1945. Hitler was at the centre of Nazi Germany, World War II in Europe, and the Random article Holocaust. Donate to Wikipedia Hitler was a decorated veteran of World War I. He joined the German Workers' Party (precursor of the NSDAP) in 1919, and became leader of the NSDAP in 1921. In 1923, he attempted a coup Interaction d'état in Munich, known as the Beer Hall Putsch. The failed coup resulted in Hitler's imprisonment, Help during which time he wrote his memoir, Mein Kampf (My Struggle). After his release in 1924, Hitler About Wikipedia gained popular support by attacking the Treaty of Versailles and promoting Pan-Germanism, Community portal antisemitism, and anti-communism with charismatic oratory and Nazi propaganda. After his Recent changes appointment as chancellor in 1933, he transformed the Weimar Republic into the Third Reich, a Contact Wikipedia single-party dictatorship based on the totalitarian and autocratic ideology of Nazism. Hitler's aim was to establish a New Order of absolute Nazi German hegemony in continental Toolbox Europe. -

Hitlerdiaries-Stern-28April1983.Pdf

Thank You for downloading this free pdf file from archive.org Stern – April 28, 1983 THE HITLER DIARIES Hitler-Tagebücher You may like this: Hitler's Third Reich – the monthly collection. 32 full issues on one Cdr - over 1600 scanned pages £5 – UK £7 – Europe £9 – Rest of World www.hitlersthirdreich.co.uk Launched in February 1999, month by month, Hitler’s Third Reich gives the facts and reveals the secrets of the most evil empire in history. Hitler’s Third Reich is the most wide-ranging history of Nazi Germany ever published. Section by section, Hitler’s Third Reich tells the complete story: THE SECRET HITLER FILES explores Hitler’s personal life – an obsessive loner with no close friends, who related better to children and dogs than with adults. INSIDE THE THIRD REICH examines every aspect of German life under Hitler and the Nazis. HITLER’S WAR MACHINE analyses the weapons and tactics with which Germany went to war. HITLER’S BATTLES follows the course of World War II through the key campaigns of the conflict. NAZI HORRORS details the gruesome crimes carried out in the Führer’s name. THE HOLOCAUST examines the most horrible of all Nazi actions: the genocidal murder of six million European Jews. THE A-Z OF THE THIRD REICH an easy to use reference source covering every aspect of the Nazi state. Ϟϟ - NAZI SYMBOLS - ϟϟ a lavishly illustrated series of articles covering the badges, uniforms, heraldry and insignia of the Third Reich. FREE PREVIEW COPY : http://www.archive.org/details/HitlersThirdReich-TheMonthlyCollectionIssue17 DUPLICATED TO AID TWO-PAGE VIEW Thank You for downloading this free pdf file from archive.org Stern – April 28, 1983 THE HITLER DIARIES Hitler-Tagebücher You may like this: Hitler's Third Reich – the monthly collection. -

PDF Download Goebbels

GOEBBELS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Peter Longerich | 992 pages | 16 Jun 2016 | Vintage Publishing | 9780099523697 | English | London, United Kingdom Joseph Goebbels | Biography, Propaganda, Death, & Facts | Britannica At this time, inflation had wrecked the German economy, and the morale of the German citizenry, who had been defeated in World War I, was low. Hitler and Goebbels were both of the opinion that words and images were potent devices that could be used to exploit this discontent. Goebbels quickly ascended the ranks of the Nazi Party. First he broke away from Gregor Strasser , the leader of the more anti-capitalistic party bloc, who he initially supported, and joined ranks with the more conservative Hitler. Then, in , he became a party district leader in Berlin. The following year, he established and wrote commentary in Der Angriff The Attack , a weekly newspaper that espoused the Nazi Party line. In , Goebbels was elected to the Reichstag, the German Parliament. More significantly, Hitler named him the Nazi Party propaganda director. It was in this capacity that Goebbels began formulating the strategy that fashioned the myth of Hitler as a brilliant and decisive leader. He arranged massive political gatherings at which Hitler was presented as the savior of a new Germany. Such events and maneuverings played a pivotal role in convincing the German people that their country would regain its honor only by giving unwavering support to Hitler. In this capacity, Goebbels had complete jurisdiction over the content of German newspapers, magazines, books, music, films, stage plays, radio programs and fine arts. His mission was to censor all opposition to Hitler and present the chancellor and the Nazi Party in the most positive light while stirring up hatred for Jewish people. -

„Die Heimat Reicht Der Front Die Hand“ Kulturelle Truppenbetreuung Im

„Die Heimat reicht der Front die Hand“ Kulturelle Truppenbetreuung im Zweiten Weltkrieg 1939-1945. Ein deutsch-englischer Vergleich. Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doktor der Philosophie der Philosophischen Fakultät der Georg-August-Universität Göttingen von Alexander Hirt Erster Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Hartmut Berghoff Zweiter Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Bernd Weisbrod INHALT Einleitung …………………………………………………………..……………………………………………..1 A. Organisationsstrukturen und Konzeption der kulturellen Truppenbetreuung 1. Organisatoren und Institutionen………………………………………………………………………..17 1.1 „Hierbei fehlt jede Kontrolle“ - Propagandaministerium, „KdF“ und Wehrmacht im polykratischen Ämterkampf……………………………………………………………………….18 1.2 „Basil Dean’s dictatorial tendencies” - NAAFI und ENSA als zentralisierteOrganisationen?...35 2. Die Konzeption der Truppenbetreuung 2.1 „Das Mädchen auf der Bretterwand ist für uns ein Wunder“ Die Anfänge organisierter Truppenbetreuung im Ersten Weltkrieg……………………………………………………...….49 2.2 „Nur mit einem Volk, das seine Nerven behält, kann man große Politik machen“ Konzeptionen vor Ausbruch des Zweiten Weltkriege………………………………………...…62 2.3 „Give us Gracie and we’ll finish the job!“ Konzeptionelle Erweiterungen und Modifizierungen im Krieg……………………………...…68 3. Die Kosten und Finanzierung der Truppenbetreuung………………………………………………...89 B. Die Umsetzung der Truppenbetreuung 1. Die Rekrutierung der Künstler 1.1 „Bevin’s surrender to the glamour of the stage“ – Das Ausschöpfen der personellen Ressourcen. Zwang oder Freiwilligkeit?.......................................................................................97