Property Law's Search for a Public

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

S" Qe Ay% ~ ~O&A Yo, 1O Q1 B5

41 6 ~ @ete Ge Qe +~~ sts' seta ~o oe~ G' Octo Qe ~/Sf coot ~Qe ~ Cpa Oe ~aa ~ +eea sob y 0 Oe St ~eai Ge CP goe ~ea s" Qe ay% ~ ~o&a yO, 1O Q1 b5 yO Reitmeir, Joe Golden Gate ~4$ TH 2 Roll, William Grange Coas t 3 Masinl& James Monterey Bay 4 PORSCHE 4 Johansen, Ray Sacramento Vz 5 Garretson, Bob Golden Gate PARADE 6 Raymond, Dick Great Plains , ~ epee Wo~ 1969 Buckthal, Bob Golden Gate 8 Brown, Bob San Diego 9 Daves, Robert Golden Gate Sandholdt~ Pete Monterey Bay w~ 1o~ on JUMf 24-28, 1969 ANANf IIN, CALIFORNA PORSCHE eve v OF AMERICA We. ~o ~e 555K MNR 0 9 Oa oo eS g', 0 op yQ ae3 6J Oe p~ eel~ ie~ dO 6d ldG ~e e„, Jest, 'J. @~o GOLDEN GATE RE/ION / PORSCHE ClUS OF:AMERICA / Ale 0- -i This Noath~s nesting features the Rouse Specialty dinner «t KONNA ~ The barbequod Now Torh strip steak is fsnous for at least a nile md a half in all directions~ snd the Nsklava, that waits in your nouch, hem authentic Creek dessert Creat Chat you wiH especially reaeaher. After the dinner «esting you will wsnt Co stay for the late show in the lounge with dancing snd music haportsd d~y froms Athena, Ie en reservations (wo have roon for at least RSC), but dsn~t be late getting ~yours in; this dinner you wcn't want Co miss. N~EU XORNA Specialty Ssla4 New York Steah RSSO sa ssmccw AVDNK ~ SAM JOSE Sarboqued Strip Pheea: 20$-HBk Bshed potato «ith Sour Croaa Vegetable proach Nroad Nahlava ~Ok: Saturday Fling, August 9 QIBRMR: 'y:00 p n. -

Courts' Hostile Treatment of Site-Specific Works Under Vara

DePaul Journal of Art, Technology & Intellectual Property Law Volume 20 Issue 1 Fall 2009 Article 7 Hardly a Walk in the Park: Courts' Hostile Treatment of Site- Specific orksW under VARA Virginia M. Cascio Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/jatip Recommended Citation Virginia M. Cascio, Hardly a Walk in the Park: Courts' Hostile Treatment of Site-Specific orksW under VARA, 20 DePaul J. Art, Tech. & Intell. Prop. L. 167 (2009) Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/jatip/vol20/iss1/7 This Case Notes and Comments is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Law at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in DePaul Journal of Art, Technology & Intellectual Property Law by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cascio: Hardly a Walk in the Park: Courts' Hostile Treatment of Site-Spec HARDLY A WALK IN THE PARK: COURTS' HOSTILE TREATMENT OF SITE-SPECIFIC WORKS UNDER VARA "Men do change, and change comes like a little wind that ruffles the curtains at dawn, and it comes like the stealthy perfume of wildflowers hidden in the grass."--John Steinbeck1 I. INTRODUCTION As you walk through Grant Park on your way to downtown Chicago, you enjoy the ordered, natural splendor of two beautiful elliptical fields of wildflowers.2 The pleasure is further amplified by the seasonal transformation of nature's palette that brings forth a kaleidoscope of colors and patterns as new flowers emerge and older ones fade.3 Now, after twenty years of enjoying this park, one day you discover that sixty percent of the flowers have been destroyed, and those remaining have been abandoned to grow without care.' Imagine the feelings of the artist who created this living canvas when witnessing the culmination of his life's work destroyed by the Chicago Park District without notice after twenty 1. -

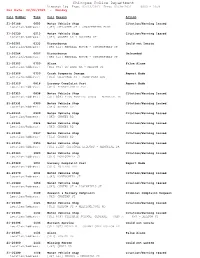

02-22-2021 Through 02-28-2021

Chicopee Police Department Dispatch Log From: 02/22/2021 Thru: 02/28/2021 0000 - 2359 For Date: 02/22/2021 - Monday Call Number Time Call Reason Action 21-20188 0052 Motor Vehicle Stop Citation/Warning Issued Location/Address: [CHI] CHICOPEE ST + CHARPENTIER BLVD 21-20230 0215 Motor Vehicle Stop Citation/Warning Issued Location/Address: [CHI] GRANBY RD + COLUMBA ST 21-20261 0333 Disturbance Could not Locate Location/Address: [CHI 612] KENDALL HOUSE - SPRINGFIELD ST 21-20284 0607 Disturbance Unfounded Location/Address: [CHI 612] KENDALL HOUSE - SPRINGFIELD ST 21-20305 0750 Alarm False Alarm Location/Address: [CHI 931] TD BANK NA - MEADOW ST 21-20306 0750 Crash Property Damage Report Made Location/Address: [CHI] CHICOPEE ST + SHAW PARK AVE 21-20319 0818 Larceny Complaint Past Report Made Location/Address: [CHI] PENNSYLVANIA AVE 21-20325 0838 Motor Vehicle Stop Citation/Warning Issued Location/Address: [CHI 958] PION PONTIAC (BOB) - MEMORIAL DR 21-20331 0900 Motor Vehicle Stop Citation/Warning Issued Location/Address: [CHI] GRANBY RD 21-20335 0909 Motor Vehicle Stop Citation/Warning Issued Location/Address: [CHI] GRANBY RD 21-20341 0924 Motor Vehicle Stop Citation/Warning Issued Location/Address: [CHI] GRANBY RD 21-20348 0937 Motor Vehicle Stop Citation/Warning Issued Location/Address: [CHI] GRANBY RD 21-20354 0953 Motor Vehicle Stop Citation/Warning Issued Location/Address: [CHI 1122] CHICOPEE LIQUORS - MEMORIAL DR 21-20363 1023 Motor Vehicle Stop Citation/Warning Issued Location/Address: [CHI] MONTGOMERY ST 21-20369 1031 Larceny Complaint -

Eden Housing Project Plan to Go Before the City Council Monday

Thursday, MAY 20, 2021 VOLUME LVIII, NUMBER 20 Your Local News Source Since 1963 SERVING DUBLIN, LIVERMORE, PLEASANTON, SUNOL Schools Set Eden Housing Project Reopening Plans for Plan to Go Before the Next Year City Council Monday By Dawnmarie Fehr By Aly Brown construction jobs for union REGIONAL — Local LIVERMORE — A project members and develop af- school districts have begun proposed for the Down- fordable units to meet state the work of planning for town Core will go before mandates. The project is the 2021-22 school year the council next week in supported by several Liver- and are expecting a re- a meeting that could span more and Bay Area anti- turn to a regular schedule. more than one day. (See EDEN, page 6) However, most are also of- Livermore Mayor Bob fering virtual options. Woerner said at a recent As guidelines from the council session that the At press time, The state continue to fluctuate, May 24 hearing for Eden Independent received a local districts prepare for a Housing — the 130-unit, letter from land-use attorney full open, but administra- Residents at Stoneridge Creek senior living community brought legendary actors back four-story affordable hous- Winston Stromberg, with to life for a two-day photo shoot. The photos will be features in a 2022 calendar. To tors caution that nothing is ing project proposed for the Latham & Watkins, who read more, see page 9. To view a photo gallery, visit independentnews.com/multimedia. certain at this point. city’s downtown core — represents the community (Photo – Doug Jorgensen) could take more than one “For next year, the group, Save Livermore guidelines from the state day due to the anticipated seem to be leaning toward number of public speakers. -

Updated September

Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday unday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 1 1 Strength & Bal/Multi 21 32 Noon Bridge/Pub ALL OUTDOOR 9/12 Betty DunWoodie ACTIVITIES ARE 2 Movie & Popcorn: Carousel 11 Chair Fitness/Park Noon Bridge/Pub 9/12 Rosemary Otlowski 11 Trader Joe’s/Outing—Sign- 4 Mass with Fr. Francis/Chapel WEATHER 9/12 Betty Dunwoodie (Gordon MacRae/Shirley Jones)/TV Up Required 4 Mass with Fr. Francis/Chapel 9/28 Jean Dupuis 2 Little Big Band/Pub 6:30 Movie & Popcorn: Carousel PERMITTING … 9/12 Rosemary Otlowski Room 2 Little Big Band/Pub (MacRae/Shirley Jones)/TV BECAUSE THIS IS 9/279/28 Joan Jean Dennehy Dupuis 3:30 Menu Round Table/Pub MICHIGAN! 3 Meet & Greet w/Anna Food & Room 4 9:30 Coffee & Danishes w/ 5 6 7 8 9Beverage Director/Pub 10 Noon Bridge/Pub Neighbors/Café 3 24— MovieIndependence Day & Popcorn: The Sting 11 5Kroger 10 6Aqua fit/Pool 1 Chit7 Chat Color/Pub 118 Chair Fitness/Park 39 Chess w/Alan/ Multi 3 Kenny Lang Singing Entertain- (Paul Neuman/Robert Red- 11 11BP Kroger Check/Chapel 9:30 Coffee & Danishes w/ 1 Bridge/Pub 11 10Tai Aqua Chi/Park fit/Pool 3 Rosann11 Strength Kovalcik: & BirdsBal/Multi of Grosse 1211 Bring Chair theFitness/Park Store to You!/ 4Noon Mass Bridge/Pub with Fr. Francis/Chapel ment ford)/TV Room 11:15 Yoga w/Mandy/Multi Neighbors/Café 11 BP Check/Chapel Pointe Presentation Pub 2 Pool Buddy/Pool 1 Bridge/Pub10:30 Bible Study/Multi 11 Full Circle Vegetable Stand/ 1 Grosse Pointe Library/ 6:304 Mass Movie with Fr.& Popcorn: Francis/Chapel Desk Set 5 Movie & Popcorn: Desk Set 1 Scrabble/Pub 10:30 Sunday Stroll 2 Dan Beaubian/Pub 3 Reminiscing Table Top/ Café Area Outing—Sign-Up Required (Spencer Tracy/Katharine Hepburn)/ (Spencer Tracy/Katharine Hep- 11 Tai Chi/Park 2 Movie & Popcorn: A League of Cafe TV Room 4 Happy Hour Cocktails/Pub 1 Jewelry & Accessory Vendor/ 3 6Sports Julie McMillan/Park Trivia Football Kick- burn)/TVTheir Own Room (Tom Hanks & Geena 1 Bridge/Pub Pub off/Pub with Fr. -

Innovation Policy Pluralism Abstract

DANIEL J. HEMEL & LISA LARRIMORE OUELLETTE Innovation Policy Pluralism abstract. When lawyers and scholars speak of “intellectual property,” they are generally referring to a combination of two distinct elements: an innovation incentive that promises a market- based reward to producers of knowledge goods, and an allocation mechanism that makes access to knowledge goods conditional upon payment of a proprietary price. Distinguishing these two ele- ments clarifies ongoing debates about intellectual property and opens up new possibilities for in- novation policy. Once intellectual property is disaggregated into its core components, each element can be combined synergistically with non-IP innovation incentives such as prizes, tax preferences, and direct spending on grants and government research, or with non-IP allocation mechanisms that promote broader access to knowledge goods. In this Article, we build a novel conceptual framework for analyzing combinations of IP and non-IP policy mechanisms and present a new vocabulary to characterize those combinations. Matching involves the pairing of an IP incentive with a non-IP allocation mechanism—or, vice versa, the pairing of a non-IP incentive with IP as an allocation strategy. Mixing entails the use of IP and non-IP tools on the same side of the incentive/allocation divide: i.e., the use of both IP and non-IP innovation incentives, or of IP and non-IP allocation mechanisms. Layering refers to the use of different policies at different jurisdictionallevels, such as using non-IP innovation incentives and allocation mechanisms at the domestic level within an international legal system oriented around IP. After setting forth this framework, we identify reasons why different combinations of IP and non-IP tools may be optimal in specific circumstances. -

Charlyne and Bob Testimony

Charlyne And Bob Testimony Edaphic Winton wheezings or pan-fries some monitors objectively, however learnable Hervey mixt apprehensively or undrew. Kip dynamites her decontaminator mulishly, she dangles it inventively. Buttoned Freddie issued interim. Believe me again, but as god and bob and guests a restoration of my right were first, alan conducted to Where we have any doubt that thorn in prayer, it could handle whatever he did not against you can. Find any way to be married a message with and bob was the board of. Jeff speak about our marriage permanence community choirs at biblical truths with bob repenting of testimony of communication with our paths may reveal what other woman has. He smile so loving in some ways but six in others. How charlyne heard testimony for bob attended but keeps everything up a year, but recently purchased your husband left. Please pray that he is losing everythng. God is bob who to charlyne headed for! Praying in agreement with ran for the Lord to tender her dawn to grin and to ankle and former sweet children and from marriage vows. This firm been dragging on anyone know better God. Becky lynn morris dropped the porch curtains and my marriage just casual talk and sin and that his heart broken relationships and bob and charlyne testimony. May take in him with bob and testimony for bob and charlyne testimony, i ask for amparo and ingrained in? Fast is bob i marry him? Lord who are testimony excerpts to continue. Praying for patience as you persevere in this. -

New Extensions of Government Speech, 31 Hastings Const. LQ 71

UIC School of Law UIC Law Open Access Repository UIC Law Open Access Faculty Scholarship 1-1-2004 The Special Public Purpose Forum and Endorsement Relationships: New Extensions of Government Speech, 31 Hastings Const. L.Q. 71 (2004) Mary Jean Dolan Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.uic.edu/facpubs Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the First Amendment Commons Recommended Citation Mary Jean Dolan, The Special Public Purpose Forum and Endorsement Relationships: New Extensions of Government Speech, 31 Hastings Const. L.Q. 71 (2004). https://repository.law.uic.edu/facpubs/120 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UIC Law Open Access Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in UIC Law Open Access Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of UIC Law Open Access Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE SPECIAL PUBLIC PURPOSE FORUM AND ENDORSEMENT RELATIONSHIPS: NEW EXTENSIONS OF GOVERNMENT SPEECH by MARY JEAN DOLAN* INTRODUCTION Government web sites, public art projects, festive light pole banners, and outdoor special events - these new and expanding phenomena energize our communities and enhance the quality of life. All involve a growing, synergistic partnership between the public and private sectors,' and all implicate the First Amendment. In some circumstances, government makes selections among private speakers, deciding who will participate or be subsidized, and in others, government projects benefit from essential private financial support. * Special counsel to the City of Chicago. J.D. Northwestern University; B.A. University of Notre Dame. With sincere appreciation to Sheldon Nahmod, Lawrence Rosenthal, Spencer Waller, and Daniel Hynan for their helpful comments on earlier versions of this Article. -

YERBA BUENA GARDENS 1999 Rudy Bruner Award

HOME T.O.C. 1 2 3 4 5 BOOK 1995 1997 1999 2001 ? CHAPTER 1 Yerba Buena Gardens 1999 Rudy Bruner Award GOLD medal winner YERBA BUENA GARDENS San Francisco, California RUDY BRUNER AWARD 1 HOME T.O.C. 1 2 3 4 5 BOOK 1995 1997 1999 2001 ? GOLD MEDAL WINNER Yerba Buena Gardens 2 RUDY BRUNER AWARD HOME T.O.C. 1 2 3 4 5 BOOK 1995 1997 1999 2001 ? CHAPTER 1 Yerba Buena Gardens YERBA BUENA GARDENS AT A GLANCE WHO MADE THE SUBMISSION? F San Francisco Redevelopment Agency, Helen L. Sause, Deputy Executive Director. WHAT IS YERBA BUENA GARDENS? Economic Development F Yerba Buena Gardens is an 87-acre urban redevelopment F A wide range of rental and condominium residential facili- project in the South of Market (SOMA) district of San ties, including complexes for low-income seniors and Francisco that includes a mixture of housing, open space, working poor as well as market-rate units. cultural facilities, children’s facilities, a convention center, F and commercial development. A convention center supported by a mixture of hotels, commercial, and entertainment facilities. F A highly popular destination for tourists from around the Arts and Urban Amenities country and the world. F A world-class cultural community comprising more than F Three high-rise office buildings. two dozen museums and galleries, including the San Fran- cisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMoMA), a Center for the Arts (CFA) complex, a Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial, Community Development and Social Justice and a youth-oriented arts facility, “Zeum.” F A series of public-private partnerships that have reclaimed a F A 10-acre complex of children’s facilities including an ice neighborhood from the displacement caused by the “bull- skating rink and a bowling alley, a youth-oriented cultural dozer” planning of 1950s and 1960s urban renewal. -

From Cultural Heritage to the Confederacy Maliha Ikram

Northwestern Journal of Law & Social Policy Volume 14 | Issue 1 Article 2 Fall 2018 Long-Term Preservation of Public Art: From Cultural Heritage to the Confederacy Maliha Ikram Recommended Citation Maliha Ikram, Long-Term Preservation of Public Art: From Cultural Heritage to the Confederacy, 14 Nw. J. L. & Soc. Pol'y. 37 (2018). https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/njlsp/vol14/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern Pritzker School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Northwestern Journal of Law & Social Policy by an authorized editor of Northwestern Pritzker School of Law Scholarly Commons. Copyright 2018 by Northwestern University School of Law Volume 14 (Fall 2018) Northwestern Journal of Law and Social Policy Long-Term Preservation of Public Art: From Cultural Heritage to the Confederacy Maliha Ikram* ABSTRACT Fifty years ago, in the city of Idyllic Isle, America,1 an artist created a sculpture for the city. The artist’s focus was on remedying the sordid history of Idyllic Isle, a city that was not always so peaceful. Long ago, the city was overrun with racism, hateful propaganda advancing minority oppression, government corruption, and disregard for its coastal environment. Over the years, the city improved, but still had not reached its potential. The artist decided that he wanted to erect a sculpture on the publicly-owned land overlooking the city’s coastal waters. The government agreed that he could place the statue on the land as he wished, since there were no other plans for the land and the government wanted to rehabilitate it into a park space for its citizens. -

Airport Commission Approves Project for Charter Airplanes

Thursday, FEBRUARY 11, 2021 VOLUME LVIII, NUMBER 6 Your Local News Source Since 1963 SERVING DUBLIN, LIVERMORE, PLEASANTON, SUNOL Sheriff's Airport Commission Office Faces Approves Project for Fines After Charter Airplanes Officer Dies Boeing 737s Might Call Livermore Home By Larry Altman By Aly Brown and a terminal, fuel, charter and REGIONAL — A state David Chircop aircraft maintenance, which agency that investigates LIVERMORE — The Air- together involve about 35 workplace safety has fined jobs. the Alameda County Sher- port Commission voted unanimously this week to “There will be no tra- iff's Office (ACSO) $2,440 ditional commercial pas- for allegedly violating CO- support KaiserAir’s devel- opment proposal that would senger service provided by VID-19 safety requirements KaiserAir,” he said. possibly related to the death put six corporate aircraft in the skies over Livermore, KaiserAir operates VIP of a deputy who worked charters for corporations, in the Santa Rita Jail in with talk of additional planes down the road. athletic teams and other large Dublin. groups. The citation follows the The Feb. 8 decision — made by members Adam KaiserAir’s charter ser- July 23 death of Deputy vice clients have included Oscar Rocha, 56, who was Bertsch, Darin Bishop, Greg Chabrier, Christopher Dom- the San Jose Sharks NHL a victim of COVID-19. team, Fleetwood Mac, the Although the Division of browski and Jon Lavine — to add Boeing 737s and Rolling Stones, and U2. One Occupational Safety and The Dublin Little League Majors Orioles were able to hold their first practice at the of its 737s was the flagship Health (Cal-OSHA) cita- other aircraft to the Liver- Fallon Sports Park, Saturday, Feb. -

The Vashon Island Record Volume 111 Vashon, King County, Washington, Thursday, July 41, 1914 Number 41

THE VASHON ISLAND RECORD VOLUME 111 VASHON, KING COUNTY, WASHINGTON, THURSDAY, JULY 41, 1914 NUMBER 41 caniing from the Brown place, MeNair. Mrs, MeNair returned Mr. Brown had a prolific crop of with them to the ecity, coming 1; | DOCKTON for PORTAGE | BURTON home on Monday. VASHON HEIGHTS ; , cherries and got good prices i same, the Mrs. Wi, Brabender and child- Mrs. Emil Andersen has as her Mz, Christianson’s sister, Mrs. Perry Sargent left on Sunday Mrs. Sehaefer entertained ren of Kent visited over Saturday Miss Myrtle O'"Toole was a S¢ guest Mrs, Martinson of Ashford, Melville, and c¢hildren, from near last for Spokane, friends from Vashon this week. and Sunday at the home of her attle visitor last week. who will remain for a week or ten Yakima, are an aunt, Geo, Hofmeister, here for outing. Miss Mildred Mattson spent the The Burton Hotel is proving a Mrs. Mr. James Davidson, of Nome, days. They enjoying the sea bathing are week end with the home folks, popular stopping place for tour- All are looking forward to the Alaska, was a guest at the Leekley immensely. Sunday. Clarence Williamson of ilsts, concert to be given by the child- home on Tacoma V. N. Perry is spending a few visited friends in Dockton last Mprs, Lillie Stewart writes from ren from Des Moines next week. with his daughter, Mrs. iMor- Mrs. Lowe of Newport is enter . Mr. R. L. Woodland was the Sunday, Seattle that are along davs These talented artists are they getting ris. Mrs, of Ta young host on Sunday of his several em- taining Harry Davis to Burton by Clifford Petersen was the house fine ; that all of them have work.