YERBA BUENA GARDENS 1999 Rudy Bruner Award

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FY 18-19 Annual Report

YERBA BUENA DISCOVER THE UNEXPECTED YBCBD ANNUAL REPORT 2018–2019 DISCOVER THE UNEXPECTED Dear Friends and Neighbors, ARTIST JR CREATES AN ORIGINAL MURAL IN YERBA BUENA It’s certain that residents, workers, and visitors to Yerba Buena will experience something new, exciting, and inspiring. The neighborhood’s tapestry is one of renown museums and galleries, landscaped gardens, and major convention facilities. There are unique places to dine, shop, and play. Amid all of this is an exhibition of public art, culinary and architectural excellence, and CITY AT NIGHT: YERBA BUENA UNDER A FULL MOON entertainment offerings unique to the city. To sustain and improve Yerba Buena’s unique characteristics, the YBCBD provides services to help make the neighborhood cleaner, safer, and even more inviting. Thank you to all who help us make Yerba Buena an exceptional place for people of all ages and backgrounds. It’s been an exciting and productive year. We’re thrilled that public art and artistry in the neighborhood grew to new heights — adding to unexpected moments of inspiration and wonder. As part of the Moscone Center expansion, there are now several new works of public art in and around the Moscone Center and Yerba Buena Gardens. The new collection augments major works that the YBCBD helped bring to the neighborhood. Yerba Buena’s ingenuity also extends to its renowned restaurants, architecture, and landscaped spaces. It is reflected in the hundreds of different performances each year of the Yerba Buena Gardens Festival, at the YBCBD’s annual Yerba Buena Night of music, dance and performance, and at our monthly theatrical neighborhood walks. -

Leandro Erlich: Towards a Collaborative Relationship Between Architecture and Art Isabel Tassara [email protected]

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Master's Projects and Capstones Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects Winter 12-16-2016 Leandro Erlich: Towards A Collaborative Relationship Between Architecture and Art Isabel Tassara [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/capstone Part of the Architectural History and Criticism Commons, Contemporary Art Commons, Interior Architecture Commons, Modern Art and Architecture Commons, and the Museum Studies Commons Recommended Citation Tassara, Isabel, "Leandro Erlich: Towards A Collaborative Relationship Between Architecture and Art" (2016). Master's Projects and Capstones. 436. https://repository.usfca.edu/capstone/436 This Project/Capstone is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects at USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Projects and Capstones by an authorized administrator of USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Leandro Erlich: Towards a Collaborative Relationship Between Architecture and Art Keywords: contemporary art, museum studies, architecture, interactive installation, international artist, art exhibition, Buenos Aires Argentina, Contemporary Jewish Museum by Isabel Tassara Capstone project submitted in partial FulFillment oF the requirements For -

H. Parks, Recreation and Open Space

IV. Environmental Setting and Impacts H. Parks, Recreation and Open Space Environmental Setting The San Francisco Recreation and Park Department maintains more than 200 parks, playgrounds, and open spaces throughout the City. The City’s park system also includes 15 recreation centers, nine swimming pools, five golf courses as well as tennis courts, ball diamonds, athletic fields and basketball courts. The Recreation and Park Department manages the Marina Yacht Harbor, Candlestick (Monster) Park, the San Francisco Zoo, and the Lake Merced Complex. In total, the Department currently owns and manages roughly 3,380 acres of parkland and open space. Together with other city agencies and state and federal open space properties within the city, about 6,360 acres of recreational resources (a variety of parks, walkways, landscaped areas, recreational facilities, playing fields and unmaintained open areas) serve San Francisco.172 San Franciscans also benefit from the Bay Area regional open spaces system. Regional resources include public open spaces managed by the East Bay Regional Park District in Alameda and Contra Costa counties; the National Park Service in Marin, San Francisco and San Mateo counties as well as state park and recreation areas throughout. In addition, thousands of acres of watershed and agricultural lands are preserved as open spaces by water and utility districts or in private ownership. The Bay Trail is a planned recreational corridor that, when complete, will encircle San Francisco and San Pablo Bays with a continuous 400-mile network of bicycling and hiking trails. It will connect the shoreline of all nine Bay Area counties, link 47 cities, and cross the major toll bridges in the region. -

S" Qe Ay% ~ ~O&A Yo, 1O Q1 B5

41 6 ~ @ete Ge Qe +~~ sts' seta ~o oe~ G' Octo Qe ~/Sf coot ~Qe ~ Cpa Oe ~aa ~ +eea sob y 0 Oe St ~eai Ge CP goe ~ea s" Qe ay% ~ ~o&a yO, 1O Q1 b5 yO Reitmeir, Joe Golden Gate ~4$ TH 2 Roll, William Grange Coas t 3 Masinl& James Monterey Bay 4 PORSCHE 4 Johansen, Ray Sacramento Vz 5 Garretson, Bob Golden Gate PARADE 6 Raymond, Dick Great Plains , ~ epee Wo~ 1969 Buckthal, Bob Golden Gate 8 Brown, Bob San Diego 9 Daves, Robert Golden Gate Sandholdt~ Pete Monterey Bay w~ 1o~ on JUMf 24-28, 1969 ANANf IIN, CALIFORNA PORSCHE eve v OF AMERICA We. ~o ~e 555K MNR 0 9 Oa oo eS g', 0 op yQ ae3 6J Oe p~ eel~ ie~ dO 6d ldG ~e e„, Jest, 'J. @~o GOLDEN GATE RE/ION / PORSCHE ClUS OF:AMERICA / Ale 0- -i This Noath~s nesting features the Rouse Specialty dinner «t KONNA ~ The barbequod Now Torh strip steak is fsnous for at least a nile md a half in all directions~ snd the Nsklava, that waits in your nouch, hem authentic Creek dessert Creat Chat you wiH especially reaeaher. After the dinner «esting you will wsnt Co stay for the late show in the lounge with dancing snd music haportsd d~y froms Athena, Ie en reservations (wo have roon for at least RSC), but dsn~t be late getting ~yours in; this dinner you wcn't want Co miss. N~EU XORNA Specialty Ssla4 New York Steah RSSO sa ssmccw AVDNK ~ SAM JOSE Sarboqued Strip Pheea: 20$-HBk Bshed potato «ith Sour Croaa Vegetable proach Nroad Nahlava ~Ok: Saturday Fling, August 9 QIBRMR: 'y:00 p n. -

201Third Street

THIRD STREET • Class A building featuring flexible,201 +29,000 RSF floor plates • 346,538 Square feet across 12 stories • Desirable SOMA location in the center of the City’s most active sub-market • Over 150 restaurants, 10 hotels and 6 forms of public transportation within a 6 block radius • AT&T Park, SF MoMA, Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, Moscone Center, Metreon Mall and Westfield Centre all within a 10 minute walk • Recently completed exterior improvements include full building exterior painting, sculptural address signage, deck with seating, updated landscape design and new building entry • Main lobby improvements recently completed include lobby expansion, new security console, state-of-the-art security systems, lounge seating and new management office • LEED Gold certified and Energy Star rated • On-site parking • Starbucks and Fogo de Chao on-site • On-site property management OWNED AND MANAGED BY Christopher T. Roeder Ted Davies Michael DeMaria International Director Managing Director Vice President 415 395 4971 415 395 4972 415 395 7248 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] License #: 01190523 License #: 01460185 License #: 01366535 BAYBAY ST. ST. FRANCISCOFRANCISCO ST. ST. 101101 CHESTNUTCHESTNUT ST. ST. HARRISHARRIS PL. PL. LOMBARDLOMBARD ST. ST. GREENWICHGREENWICH ST. ST. 101101 JEFFERSONJEFFERSON ST. ST. FILBERT ST. COLUMBUS ST. FILBERT ST. COLUMBUS ST. UNIONUNION ST. ST. BEACHBEACH ST. ST. OCTAVIAOCTAVIA ST. ST. NORTHPOINT ST. GREENGREEN ST. ST. NORTHPOINT ST. GOUGHGOUGH ST. ST. VALLEJOVALLEJO ST. ST. BAYBAY ST. ST. FRANKLINFRANKLIN ST. ST. BROADWAYBROADWAY FRANCISCOFRANCISCO ST. ST. VANVAN NESS NESS AVE. AVE. PACIFICPACIFIC AVE. AVE. CHESTNUTCHESTNUT ST. -

PRESS RELEASE** SFMTA Weekend Transit and Traffic Advisory for Saturday, September 14, 2019

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE September 12, 2019 Contact: Erica Kato [email protected] **PRESS RELEASE** SFMTA Weekend Transit and Traffic Advisory For Saturday, September 14, 2019 San Francisco—The San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency (SFMTA) releases the following upcoming event-related traffic and transit impacts for this weekend, from Thursday, September 12 through Monday, September 16, 2019. For real-time updates, follow us on https://twitter.com/sfmta_muni or visit https://www.sfmta.com/about-us/contact-us/email-and-text-alerts to sign up for real-time text messages or email alerts. For details of Muni re-routes, visit http://www.sfmta.com/news/alerts. This website will be updated when it is closer to the event date. For additional notifications and agency updates, subscribe to our blog, Moving SF for daily or weekly updates. San Francisco Giants Baseball Games Thursday, September 12 through Sunday, September 15: The San Francisco Giants will play four games at the ballpark: • One game against the Pittsburgh Pirates: 1) 12:45 p.m., Thursday. • Three games against the Miami Marlins: 1) 7:15 p.m., Friday; 2) 6:05 p.m., Saturday; and 3) 1:05 p.m., Sunday. For detail on parking conditions during this period and transit options to the ballpark, visit www.sfgiants.com/transportation. For details about transportation to the ballpark, including connections from Bay Area transit system to Muni, visit https://www.sfmta.com/places/oracle-park. Baseball fans can purchase one-way Muni tickets at two ticket vending machines located next to the ball park ticket window at the corner of King and 2nd streets. -

One Liberty Plaza

THE MONADNOCK BUILDING General Description The Monadnock Building is a historic 10-story, 204,625 square foot office building in downtown San Francisco located at the confluence of the North and South Financial districts and the world-renowned Union Square shopping district. Built in 1906, The Monadnock Building is an exquisite example of turn-of-the-century “Beaux Arts” style and its storied place in San Francisco’s history makes it one of the city’s most well known landmark properties. Design Architect Frederick H. Meyer and Smith O’Brien (original) Whisler-Patri and Charles Pfister (1986 renovation) General Contractor Swinerton Wahlberg Construction (1986 renovation) Mechanical Engineer Tenant Improvement Work: Amit Wadhwa & Associates Structural Engineer Sattary Engineering Completion Date 1906 Renovated 1986-1990 Building Height 10 stories Design Load 20 pounds per square foot partition load 40-50 pounds per square foot live load Rentable Area Approximately 204,625 RSF Typical Floor Area Approximately 20,000 SF Ceiling Heights Slab to Slab: 12’6” (Typical) Finished: 8’6” (Typical) Mullion Spacing 15’0” on center (Typical) Exterior Column Spacing 20’0” on center (Typical) HEATING, VENTILATION Hydronic Heat Pump; 20 to 28 zones per floor AND AIR CONDITIONING Design Criteria The building is equipped with hydronic heat pumps located throughout the building. Individual heat pumps are controlled via dedicated standalone conventional thermostats. HVAC on each floor is supervised by a central 7day mechanical time clock. Heat Heat is supplied by electric strip heaters located within the perimeter VAV boxes. Air Conditioning Cooling is provided by cooled air delivered to all VAV boxes from a central floor fan. -

Changemakers: Biographies of African Americans in San Francisco Who Made a Difference

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Leo T. McCarthy Center for Public Service and McCarthy Center Student Scholarship the Common Good 2020 Changemakers: Biographies of African Americans in San Francisco Who Made a Difference David Donahue Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/mccarthy_stu Part of the History Commons CHANGEMAKERS AFRICAN AMERICANS IN SAN FRANCISCO WHO MADE A DIFFERENCE Biographies inspired by San Francisco’s Ella Hill Hutch Community Center murals researched, written, and edited by the University of San Francisco’s Martín-Baró Scholars and Esther Madríz Diversity Scholars CHANGEMAKERS: AFRICAN AMERICANS IN SAN FRANCISCO WHO MADE A DIFFERENCE © 2020 First edition, second printing University of San Francisco 2130 Fulton Street San Francisco, CA 94117 Published with the generous support of the Walter and Elise Haas Fund, Engage San Francisco, The Leo T. McCarthy Center for Public Service and the Common Good, The University of San Francisco College of Arts and Sciences, University of San Francisco Student Housing and Residential Education The front cover features a 1992 portrait of Ella Hill Hutch, painted by Eugene E. White The Inspiration Murals were painted in 1999 by Josef Norris, curated by Leonard ‘Lefty’ Gordon and Wendy Nelder, and supported by the San Francisco Arts Commission and the Mayor’s Offi ce Neighborhood Beautifi cation Project Grateful acknowledgment is made to the many contributors who made this book possible. Please see the back pages for more acknowledgments. The opinions expressed herein represent the voices of students at the University of San Francisco and do not necessarily refl ect the opinions of the University or our sponsors. -

Courts' Hostile Treatment of Site-Specific Works Under Vara

DePaul Journal of Art, Technology & Intellectual Property Law Volume 20 Issue 1 Fall 2009 Article 7 Hardly a Walk in the Park: Courts' Hostile Treatment of Site- Specific orksW under VARA Virginia M. Cascio Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/jatip Recommended Citation Virginia M. Cascio, Hardly a Walk in the Park: Courts' Hostile Treatment of Site-Specific orksW under VARA, 20 DePaul J. Art, Tech. & Intell. Prop. L. 167 (2009) Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/jatip/vol20/iss1/7 This Case Notes and Comments is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Law at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in DePaul Journal of Art, Technology & Intellectual Property Law by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cascio: Hardly a Walk in the Park: Courts' Hostile Treatment of Site-Spec HARDLY A WALK IN THE PARK: COURTS' HOSTILE TREATMENT OF SITE-SPECIFIC WORKS UNDER VARA "Men do change, and change comes like a little wind that ruffles the curtains at dawn, and it comes like the stealthy perfume of wildflowers hidden in the grass."--John Steinbeck1 I. INTRODUCTION As you walk through Grant Park on your way to downtown Chicago, you enjoy the ordered, natural splendor of two beautiful elliptical fields of wildflowers.2 The pleasure is further amplified by the seasonal transformation of nature's palette that brings forth a kaleidoscope of colors and patterns as new flowers emerge and older ones fade.3 Now, after twenty years of enjoying this park, one day you discover that sixty percent of the flowers have been destroyed, and those remaining have been abandoned to grow without care.' Imagine the feelings of the artist who created this living canvas when witnessing the culmination of his life's work destroyed by the Chicago Park District without notice after twenty 1. -

100 Things to Do in San Francisco*

100 Things to Do in San Francisco* Explore Your New Campus & City MORNING 1. Wake up early and watch the sunrise from the top of Bernal Hill. (Bernal Heights) 2. Uncover antique treasures and designer deals at the Treasure Island Flea Market. (Treasure Island) 3. Go trail running in Glen Canyon Park. (Glen Park) 4. Swim in Aquatic Park. (Fisherman's Wharf) 5. Take visitors to Fort Point at the base of the Golden Gate Bridge, where Kim Novak attempted suicide in Hitchcock's Vertigo. (Marina) 6. Get Zen on Sundays with free yoga classes in Dolores Park. (Dolores Park) 7. Bring Your Own Big Wheel on Easter Sunday. (Potrero Hill) 8. Play tennis at the Alice Marble tennis courts. (Russian Hill) 9. Sip a cappuccino on the sidewalk while the cable car cruises by at Nook. (Nob Hill) 10. Take in the views from seldom-visited Ina Coolbrith Park and listen to the sounds of North Beach below. (Nob Hill) 11. Brave the line at the Swan Oyster Depot for fresh seafood. (Nob Hill) *Adapted from 7x7.com 12. Drive down one of the steepest streets in town - either 22nd between Vicksburg and Church (Noe Valley) or Filbert between Leavenworth and Hyde (Russian Hill). 13. Nosh on some goodies at Noe Valley Bakery then shop along 24th Street. (Noe Valley) 14. Play a round of 9 or 18 at the Presidio Golf Course. (Presidio) 15. Hike around Angel Island in spring when the wildflowers are blooming. 16. Dress up in a crazy costume and run or walk Bay to Breakers. -

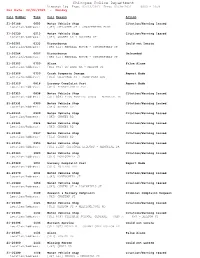

02-22-2021 Through 02-28-2021

Chicopee Police Department Dispatch Log From: 02/22/2021 Thru: 02/28/2021 0000 - 2359 For Date: 02/22/2021 - Monday Call Number Time Call Reason Action 21-20188 0052 Motor Vehicle Stop Citation/Warning Issued Location/Address: [CHI] CHICOPEE ST + CHARPENTIER BLVD 21-20230 0215 Motor Vehicle Stop Citation/Warning Issued Location/Address: [CHI] GRANBY RD + COLUMBA ST 21-20261 0333 Disturbance Could not Locate Location/Address: [CHI 612] KENDALL HOUSE - SPRINGFIELD ST 21-20284 0607 Disturbance Unfounded Location/Address: [CHI 612] KENDALL HOUSE - SPRINGFIELD ST 21-20305 0750 Alarm False Alarm Location/Address: [CHI 931] TD BANK NA - MEADOW ST 21-20306 0750 Crash Property Damage Report Made Location/Address: [CHI] CHICOPEE ST + SHAW PARK AVE 21-20319 0818 Larceny Complaint Past Report Made Location/Address: [CHI] PENNSYLVANIA AVE 21-20325 0838 Motor Vehicle Stop Citation/Warning Issued Location/Address: [CHI 958] PION PONTIAC (BOB) - MEMORIAL DR 21-20331 0900 Motor Vehicle Stop Citation/Warning Issued Location/Address: [CHI] GRANBY RD 21-20335 0909 Motor Vehicle Stop Citation/Warning Issued Location/Address: [CHI] GRANBY RD 21-20341 0924 Motor Vehicle Stop Citation/Warning Issued Location/Address: [CHI] GRANBY RD 21-20348 0937 Motor Vehicle Stop Citation/Warning Issued Location/Address: [CHI] GRANBY RD 21-20354 0953 Motor Vehicle Stop Citation/Warning Issued Location/Address: [CHI 1122] CHICOPEE LIQUORS - MEMORIAL DR 21-20363 1023 Motor Vehicle Stop Citation/Warning Issued Location/Address: [CHI] MONTGOMERY ST 21-20369 1031 Larceny Complaint -

Eden Housing Project Plan to Go Before the City Council Monday

Thursday, MAY 20, 2021 VOLUME LVIII, NUMBER 20 Your Local News Source Since 1963 SERVING DUBLIN, LIVERMORE, PLEASANTON, SUNOL Schools Set Eden Housing Project Reopening Plans for Plan to Go Before the Next Year City Council Monday By Dawnmarie Fehr By Aly Brown construction jobs for union REGIONAL — Local LIVERMORE — A project members and develop af- school districts have begun proposed for the Down- fordable units to meet state the work of planning for town Core will go before mandates. The project is the 2021-22 school year the council next week in supported by several Liver- and are expecting a re- a meeting that could span more and Bay Area anti- turn to a regular schedule. more than one day. (See EDEN, page 6) However, most are also of- Livermore Mayor Bob fering virtual options. Woerner said at a recent As guidelines from the council session that the At press time, The state continue to fluctuate, May 24 hearing for Eden Independent received a local districts prepare for a Housing — the 130-unit, letter from land-use attorney full open, but administra- Residents at Stoneridge Creek senior living community brought legendary actors back four-story affordable hous- Winston Stromberg, with to life for a two-day photo shoot. The photos will be features in a 2022 calendar. To tors caution that nothing is ing project proposed for the Latham & Watkins, who read more, see page 9. To view a photo gallery, visit independentnews.com/multimedia. certain at this point. city’s downtown core — represents the community (Photo – Doug Jorgensen) could take more than one “For next year, the group, Save Livermore guidelines from the state day due to the anticipated seem to be leaning toward number of public speakers.