Innovation Policy Pluralism Abstract

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DOLPHIN RESEARCH CENTER Legends & Myths & More!

DOLPHIN RESEARCH CENTER Legends & Myths & More! Grade Level: 3rd -5 th Objectives: Students will construct their own meaning from a variety of legends and myths about dolphins and then create their own dolphin legend or myth. Florida Sunshine State Standards: Language Arts LA.A.2.2.5 The student reads and organizes information for a variety of purposes, including making a report, conducting interviews, taking a test, and performing an authentic task. LA.B.1.2 The student uses the writing processes effectively. Social Studies SS.A.1.2.1: The student understands how individuals, ideas, decisions, and events can influence history. SS.B.2.2.4: The student understands how factors such as population growth, human migration, improved methods of transportation and communication, and economic development affect the use and conservation of natural resources. Science SC.G.1.2.2 The student knows that living things compete in a climatic region with other living things and that structural adaptations make them fit for an environment. National Science Education Standards: Content Standard C (K-4) - Characteristics of Organisms : Each plant or animal has different structures that serve different functions in growth, survival, and reproduction. For example, humans have distinct body structures for walking, holding, seeing, and talking. Content Standard C (5-8) - Diversity and adaptations of Organisms : Biological evolution accounts for the diversity of species developed through gradual processes over many generations. Species acquire many of their unique characteristics through biological adaptation, which involves the selection of naturally occurring variations in populations. Biological adaptations include changes in structures, behaviors, or physiology that enhance survival and reproductive success in a particular environment. -

Cognitive Adaptations of Social Bonding in Birds Nathan J

Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B (2007) 362, 489–505 doi:10.1098/rstb.2006.1991 Published online 24 January 2007 Cognitive adaptations of social bonding in birds Nathan J. Emery1,*, Amanda M. Seed2, Auguste M. P. von Bayern1 and Nicola S. Clayton2 1Sub-department of Animal Behaviour, University of Cambridge, Cambridge CB3 8AA, UK 2Department of Experimental Psychology, University of Cambridge, Cambridge CB2 3EB, UK The ‘social intelligence hypothesis’ was originally conceived to explain how primates may have evolved their superior intellect and large brains when compared with other animals. Although some birds such as corvids may be intellectually comparable to apes, the same relationship between sociality and brain size seen in primates has not been found for birds, possibly suggesting a role for other non-social factors. But bird sociality is different from primate sociality. Most monkeys and apes form stable groups, whereas most birds are monogamous, and only form large flocks outside of the breeding season. Some birds form lifelong pair bonds and these species tend to have the largest brains relative to body size. Some of these species are known for their intellectual abilities (e.g. corvids and parrots), while others are not (e.g. geese and albatrosses). Although socio-ecological factors may explain some of the differences in brain size and intelligence between corvids/parrots and geese/albatrosses, we predict that the type and quality of the bonded relationship is also critical. Indeed, we present empirical evidence that rook and jackdaw partnerships resemble primate and dolphin alliances. Although social interactions within a pair may seem simple on the surface, we argue that cognition may play an important role in the maintenance of long-term relationships, something we name as ‘relationship intelligence’. -

S" Qe Ay% ~ ~O&A Yo, 1O Q1 B5

41 6 ~ @ete Ge Qe +~~ sts' seta ~o oe~ G' Octo Qe ~/Sf coot ~Qe ~ Cpa Oe ~aa ~ +eea sob y 0 Oe St ~eai Ge CP goe ~ea s" Qe ay% ~ ~o&a yO, 1O Q1 b5 yO Reitmeir, Joe Golden Gate ~4$ TH 2 Roll, William Grange Coas t 3 Masinl& James Monterey Bay 4 PORSCHE 4 Johansen, Ray Sacramento Vz 5 Garretson, Bob Golden Gate PARADE 6 Raymond, Dick Great Plains , ~ epee Wo~ 1969 Buckthal, Bob Golden Gate 8 Brown, Bob San Diego 9 Daves, Robert Golden Gate Sandholdt~ Pete Monterey Bay w~ 1o~ on JUMf 24-28, 1969 ANANf IIN, CALIFORNA PORSCHE eve v OF AMERICA We. ~o ~e 555K MNR 0 9 Oa oo eS g', 0 op yQ ae3 6J Oe p~ eel~ ie~ dO 6d ldG ~e e„, Jest, 'J. @~o GOLDEN GATE RE/ION / PORSCHE ClUS OF:AMERICA / Ale 0- -i This Noath~s nesting features the Rouse Specialty dinner «t KONNA ~ The barbequod Now Torh strip steak is fsnous for at least a nile md a half in all directions~ snd the Nsklava, that waits in your nouch, hem authentic Creek dessert Creat Chat you wiH especially reaeaher. After the dinner «esting you will wsnt Co stay for the late show in the lounge with dancing snd music haportsd d~y froms Athena, Ie en reservations (wo have roon for at least RSC), but dsn~t be late getting ~yours in; this dinner you wcn't want Co miss. N~EU XORNA Specialty Ssla4 New York Steah RSSO sa ssmccw AVDNK ~ SAM JOSE Sarboqued Strip Pheea: 20$-HBk Bshed potato «ith Sour Croaa Vegetable proach Nroad Nahlava ~Ok: Saturday Fling, August 9 QIBRMR: 'y:00 p n. -

Courts' Hostile Treatment of Site-Specific Works Under Vara

DePaul Journal of Art, Technology & Intellectual Property Law Volume 20 Issue 1 Fall 2009 Article 7 Hardly a Walk in the Park: Courts' Hostile Treatment of Site- Specific orksW under VARA Virginia M. Cascio Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/jatip Recommended Citation Virginia M. Cascio, Hardly a Walk in the Park: Courts' Hostile Treatment of Site-Specific orksW under VARA, 20 DePaul J. Art, Tech. & Intell. Prop. L. 167 (2009) Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/jatip/vol20/iss1/7 This Case Notes and Comments is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Law at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in DePaul Journal of Art, Technology & Intellectual Property Law by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cascio: Hardly a Walk in the Park: Courts' Hostile Treatment of Site-Spec HARDLY A WALK IN THE PARK: COURTS' HOSTILE TREATMENT OF SITE-SPECIFIC WORKS UNDER VARA "Men do change, and change comes like a little wind that ruffles the curtains at dawn, and it comes like the stealthy perfume of wildflowers hidden in the grass."--John Steinbeck1 I. INTRODUCTION As you walk through Grant Park on your way to downtown Chicago, you enjoy the ordered, natural splendor of two beautiful elliptical fields of wildflowers.2 The pleasure is further amplified by the seasonal transformation of nature's palette that brings forth a kaleidoscope of colors and patterns as new flowers emerge and older ones fade.3 Now, after twenty years of enjoying this park, one day you discover that sixty percent of the flowers have been destroyed, and those remaining have been abandoned to grow without care.' Imagine the feelings of the artist who created this living canvas when witnessing the culmination of his life's work destroyed by the Chicago Park District without notice after twenty 1. -

02-22-2021 Through 02-28-2021

Chicopee Police Department Dispatch Log From: 02/22/2021 Thru: 02/28/2021 0000 - 2359 For Date: 02/22/2021 - Monday Call Number Time Call Reason Action 21-20188 0052 Motor Vehicle Stop Citation/Warning Issued Location/Address: [CHI] CHICOPEE ST + CHARPENTIER BLVD 21-20230 0215 Motor Vehicle Stop Citation/Warning Issued Location/Address: [CHI] GRANBY RD + COLUMBA ST 21-20261 0333 Disturbance Could not Locate Location/Address: [CHI 612] KENDALL HOUSE - SPRINGFIELD ST 21-20284 0607 Disturbance Unfounded Location/Address: [CHI 612] KENDALL HOUSE - SPRINGFIELD ST 21-20305 0750 Alarm False Alarm Location/Address: [CHI 931] TD BANK NA - MEADOW ST 21-20306 0750 Crash Property Damage Report Made Location/Address: [CHI] CHICOPEE ST + SHAW PARK AVE 21-20319 0818 Larceny Complaint Past Report Made Location/Address: [CHI] PENNSYLVANIA AVE 21-20325 0838 Motor Vehicle Stop Citation/Warning Issued Location/Address: [CHI 958] PION PONTIAC (BOB) - MEMORIAL DR 21-20331 0900 Motor Vehicle Stop Citation/Warning Issued Location/Address: [CHI] GRANBY RD 21-20335 0909 Motor Vehicle Stop Citation/Warning Issued Location/Address: [CHI] GRANBY RD 21-20341 0924 Motor Vehicle Stop Citation/Warning Issued Location/Address: [CHI] GRANBY RD 21-20348 0937 Motor Vehicle Stop Citation/Warning Issued Location/Address: [CHI] GRANBY RD 21-20354 0953 Motor Vehicle Stop Citation/Warning Issued Location/Address: [CHI 1122] CHICOPEE LIQUORS - MEMORIAL DR 21-20363 1023 Motor Vehicle Stop Citation/Warning Issued Location/Address: [CHI] MONTGOMERY ST 21-20369 1031 Larceny Complaint -

Eden Housing Project Plan to Go Before the City Council Monday

Thursday, MAY 20, 2021 VOLUME LVIII, NUMBER 20 Your Local News Source Since 1963 SERVING DUBLIN, LIVERMORE, PLEASANTON, SUNOL Schools Set Eden Housing Project Reopening Plans for Plan to Go Before the Next Year City Council Monday By Dawnmarie Fehr By Aly Brown construction jobs for union REGIONAL — Local LIVERMORE — A project members and develop af- school districts have begun proposed for the Down- fordable units to meet state the work of planning for town Core will go before mandates. The project is the 2021-22 school year the council next week in supported by several Liver- and are expecting a re- a meeting that could span more and Bay Area anti- turn to a regular schedule. more than one day. (See EDEN, page 6) However, most are also of- Livermore Mayor Bob fering virtual options. Woerner said at a recent As guidelines from the council session that the At press time, The state continue to fluctuate, May 24 hearing for Eden Independent received a local districts prepare for a Housing — the 130-unit, letter from land-use attorney full open, but administra- Residents at Stoneridge Creek senior living community brought legendary actors back four-story affordable hous- Winston Stromberg, with to life for a two-day photo shoot. The photos will be features in a 2022 calendar. To tors caution that nothing is ing project proposed for the Latham & Watkins, who read more, see page 9. To view a photo gallery, visit independentnews.com/multimedia. certain at this point. city’s downtown core — represents the community (Photo – Doug Jorgensen) could take more than one “For next year, the group, Save Livermore guidelines from the state day due to the anticipated seem to be leaning toward number of public speakers. -

Johannes Ulf Lange Kavli Institute for Particle Astrophysics and Cosmology [email protected], Johannesulf.Github.Io

Johannes Ulf Lange Kavli Institute for Particle Astrophysics and Cosmology [email protected], johannesulf.github.io RESEARCH INTERESTS Cosmology, Large-Scale Structure, Weak Gravitational Lensing, Galaxy-Halo Connection, Galaxy Formation Theory, Statistical Methods and Machine Learning EDUCATION Yale University 08/2014 – 08/2019 M.Sc., M.Phil, Ph.D. in Astronomy Thesis Advisor: Frank van den Bosch Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg 09/2012 – 08/2014 Master of Science in Physics Freie Universität Berlin 10/2009 – 08/2012 Bachelor of Science in Physics POSITIONS Kavli Institute for Particle Astrophysics and Cosmology 09/2021 – 08/2023 Stanford–Santa Cruz Cosmology Postdoctoral Fellow University of California, Santa Cruz 09/2019 – 08/2021 Stanford–Santa Cruz Cosmology Postdoctoral Fellow FIRST-AUTHOR PUBLICATIONS [10] J. U. Lange, A. P. Hearin, A. Leauthaud, F. C. van den Bosch, H. Guo, and J. DeRose. “Five-percent measurements of the growth rate from simulation-based mod- elling of redshift-space clustering in BOSS LOWZ”. arXiv e-prints, arXiv:2101.12261 (Jan. 2021), arXiv:2101.12261. [9] J. U. Lange, A. Leauthaud, S. Singh, H. Guo, R. Zhou, T. L. Smith, and F.-Y. Cyr- Racine. “On the halo-mass and radial scale dependence of the lensing is low effect”. MNRAS 502.2 (Apr. 2021), pp. 2074–2086. [8] J. U. Lange, F. C. van den Bosch, A. R. Zentner, K. Wang, A. P. Hearin, and H. Guo. “Cosmological Evidence Modelling: a new simulation-based approach to constrain cosmology on non-linear scales”. MNRAS 490.2 (Dec. 2019), pp. 1870–1878. [7] J. U. Lange, X. Yang, H. Guo, W. -

Rattlesnake Tales 127

Hamell and Fox Rattlesnake Tales 127 Rattlesnake Tales George Hamell and William A. Fox Archaeological evidence from the Northeast and from selected Mississippian sites is presented and combined with ethnographic, historic and linguistic data to investigate the symbolic significance of the rattlesnake to northeastern Native groups. The authors argue that the rattlesnake is, chief and foremost, the pre-eminent shaman with a (gourd) medicine rattle attached to his tail. A strong and pervasive association of serpents, including rattlesnakes, with lightning and rainfall is argued to have resulted in a drought-related ceremo- nial expression among Ontario Iroquoians from circa A.D. 1200 -1450. The Rattlesnake and Associates Personified (Crotalus admanteus) rattlesnake man-being held a special fascination for the Northern Iroquoians Few, if any of the other-than-human kinds of (Figure 2). people that populate the mythical realities of the This is unexpected because the historic range of North American Indians are held in greater the eastern diamondback rattlesnake did not esteem than the rattlesnake man-being,1 a grand- extend northward into the homeland of the father, and the proto-typical shaman and warrior Northern Iroquoians. However, by the later sev- (Hamell 1979:Figures 17, 19-21; 1998:258, enteenth century, the historic range of the 264-266, 270-271; cf. Klauber 1972, II:1116- Northern Iroquoians and the Iroquois proper 1219) (Figure 1). Real humans and the other- extended southward into the homeland of the than-human kinds of people around them con- eastern diamondback rattlesnake. By this time the stitute a social world, a three-dimensional net- Seneca and other Iroquois had also incorporated work of kinsmen, governed by the rule of reci- and assimilated into their identities individuals procity and with the intensity of the reciprocity and families from throughout the Great Lakes correlated with the social, geographical, and region and southward into Virginia and the sometimes mythical distance between them Carolinas. -

Updated September

Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday unday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 1 1 Strength & Bal/Multi 21 32 Noon Bridge/Pub ALL OUTDOOR 9/12 Betty DunWoodie ACTIVITIES ARE 2 Movie & Popcorn: Carousel 11 Chair Fitness/Park Noon Bridge/Pub 9/12 Rosemary Otlowski 11 Trader Joe’s/Outing—Sign- 4 Mass with Fr. Francis/Chapel WEATHER 9/12 Betty Dunwoodie (Gordon MacRae/Shirley Jones)/TV Up Required 4 Mass with Fr. Francis/Chapel 9/28 Jean Dupuis 2 Little Big Band/Pub 6:30 Movie & Popcorn: Carousel PERMITTING … 9/12 Rosemary Otlowski Room 2 Little Big Band/Pub (MacRae/Shirley Jones)/TV BECAUSE THIS IS 9/279/28 Joan Jean Dennehy Dupuis 3:30 Menu Round Table/Pub MICHIGAN! 3 Meet & Greet w/Anna Food & Room 4 9:30 Coffee & Danishes w/ 5 6 7 8 9Beverage Director/Pub 10 Noon Bridge/Pub Neighbors/Café 3 24— MovieIndependence Day & Popcorn: The Sting 11 5Kroger 10 6Aqua fit/Pool 1 Chit7 Chat Color/Pub 118 Chair Fitness/Park 39 Chess w/Alan/ Multi 3 Kenny Lang Singing Entertain- (Paul Neuman/Robert Red- 11 11BP Kroger Check/Chapel 9:30 Coffee & Danishes w/ 1 Bridge/Pub 11 10Tai Aqua Chi/Park fit/Pool 3 Rosann11 Strength Kovalcik: & BirdsBal/Multi of Grosse 1211 Bring Chair theFitness/Park Store to You!/ 4Noon Mass Bridge/Pub with Fr. Francis/Chapel ment ford)/TV Room 11:15 Yoga w/Mandy/Multi Neighbors/Café 11 BP Check/Chapel Pointe Presentation Pub 2 Pool Buddy/Pool 1 Bridge/Pub10:30 Bible Study/Multi 11 Full Circle Vegetable Stand/ 1 Grosse Pointe Library/ 6:304 Mass Movie with Fr.& Popcorn: Francis/Chapel Desk Set 5 Movie & Popcorn: Desk Set 1 Scrabble/Pub 10:30 Sunday Stroll 2 Dan Beaubian/Pub 3 Reminiscing Table Top/ Café Area Outing—Sign-Up Required (Spencer Tracy/Katharine Hepburn)/ (Spencer Tracy/Katharine Hep- 11 Tai Chi/Park 2 Movie & Popcorn: A League of Cafe TV Room 4 Happy Hour Cocktails/Pub 1 Jewelry & Accessory Vendor/ 3 6Sports Julie McMillan/Park Trivia Football Kick- burn)/TVTheir Own Room (Tom Hanks & Geena 1 Bridge/Pub Pub off/Pub with Fr. -

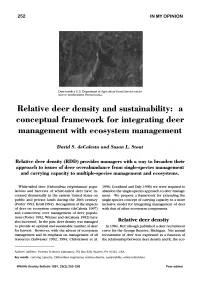

Relative Deer Density and Sustainability: a Conceptual Framework for Integrating Deer Management with Ecosystem Management

252 IN MY OPINION Deer inside a U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service enclo sure in northwestern Pennsylvania. Relative deer density and sustainability: a conceptual framework for integrating deer management with ecosystem management David S. deCalesta and Susan L. Stout Relative deer density (RDD) provides managers with a way to broaden their approach to issues of deer overabundance from single-species management and carrying capacity to multiple-species management and ecosystems. White-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) popu 1996; Goodland and Daly 1996) we were required to lations and harvests of white-tailed deer have in abandon the single-species approach to deer manage creased dramatically in the eastern United States on ment. We propose a framework for extending the public and private lands during the 20th century single-species concept of carrying capacity to a more (Porter 1992, Kroll 1994). Recognition of the impacts inclusive model for integrating management of deer of deer on ecosystem components ( deCalesta 1997) with that of other ecosystem components. and controversy over management of deer popula tions (Porter 1992, Witmer and deCalesta 1992) have also increased. In the past, deer density was managed Relative deer density to provide an optimal and sustainable number of deer In 1984, McCullough published a deer recruitment for harvest. However, with the advent of ecosystem curve for the George Reserve, Michigan. Net annual management and its emphasis on management of all recruitment of deer was expressed as a function of resources (Salwasser 1992, 1994; Christenson et al. the relationship between deer density and K, the eco- Authors' address: Forestry Sciences Laboratory, PO Box 928, Warren, PA 16365, USA. -

Yale French Studies Structuralism

Yale French Studies Structuralism Double Issue - Two Dollars Per Copy - All ArticlesIn English This content downloaded from 138.38.44.95 on Sun, 03 Jan 2016 19:52:13 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Yale French Studies THIRTY-SIX AND THIRTY-SEVEN STRUCTURALISM 5 Introduction The Editor LINGUISTICS 10 Structureand Language A ndreMartinet 19 Merleau-Pontyand thephenomenology of language PhilipE. Lewis ANTHROPOLOGY 41 Overtureto le Cru et le cuit Claude Levi-Strauss 66 Structuralismin anthropology Harold W. Scheffler ART 89 Some remarkson structuralanalysis in art and architecture SheldonNodelman PSYCHIATRY 104 JacquesLacan and thestructure of the unconscious JanMiel 112 The insistenceof the letterin the unconscious JacquesLacan LITERATURE 148 Structuralism:the Anglo-Americanadventure GeoffreyHartman 169 Structuresof exchangein Cinna JacquesEhrmann 200 Describingpoetic structures: Two approaches to Baudelaire'sles Chats Michael Riffaterre 243 Towards an anthropologyof literature VictoriaL. Rippere This content downloaded from 138.38.44.95 on Sun, 03 Jan 2016 19:52:13 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions BIBLIOGRAPHIES 252 Linguistics ElizabethBarber 256 Anthropology Allen R. Maxwell 263 JacquesLacan AnthonyG. Wilden 269 Structuralismand literarycriticism T. Todorov 270 Selectedgeneral bibliography The Editor Cover: "Graph,"photograph by JacquesEhrmann. Editor, this issue: Jacques Ehrmann; Business Manager: Bruce M. Wermuth; General Editor: Joseph H. McMahon; Assistant: Jonathan B. Talbot; Advisory Board: Henri Peyre (Chairman), Michel Beaujour, Victor Brombert, Kenneth Cornell, Georges May, Charles Porter Subscriptions:$3.50 for two years (four issues), $2.00 for one year (two issues), $1.00 per number.323 W. L. HarknessHall, Yale University,New Haven, Connecticut.Printed for YFS by EasternPress, New Haven. -

Five Minutes with Jeffrey C. Alexander: “Southern European Countries Are

Five minutes with Jeffrey C. Alexander: “Southern European countries are not just experiencing an economic crisis, but also an identity crisis” blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/2013/04/23/five-minutes-with-jeffrey-c-alexander-europe-dark-side-of-modernity/ 4/23/2013 Is there a ‘dark side’ to European modernity? As part of our ‘ Thinkers on Europe’ series, EUROPP’s editors Stuart A Brown and Chris Gilson spoke to Jeffrey C. Alexander about his views on modernity, the European integration process, and the importance of cultural and political symbols to European democracy. You’ve written about the ‘dark side’ of modernity. What is the dark side to European modernity? Well the dark side is the disappointing, dangerous side to modernity, not to mention the murder and wars. There’s a strong narrative of progress that’s associated with the idea of modernity, although it depends when you think modernity started. You might start with the Renaissance, the Reformation, the Industrial Revolution, or the Scientific Revolution, but I wanted to put “The Dark Side of Modernity” together to crystalise the idea that there has always been a dark part that offers a kind of counterpoint to the light part. And in Europe of course we think of the first half of the 20th century as a devastating period both in terms of the birth of total war and genocide. I describe modernity as ‘Janus faced’. The god Janus was a Roman god that was associated with the creation of order in the universe, but there was also the idea that disorder was always close behind.