Yale French Studies Structuralism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DOLPHIN RESEARCH CENTER Legends & Myths & More!

DOLPHIN RESEARCH CENTER Legends & Myths & More! Grade Level: 3rd -5 th Objectives: Students will construct their own meaning from a variety of legends and myths about dolphins and then create their own dolphin legend or myth. Florida Sunshine State Standards: Language Arts LA.A.2.2.5 The student reads and organizes information for a variety of purposes, including making a report, conducting interviews, taking a test, and performing an authentic task. LA.B.1.2 The student uses the writing processes effectively. Social Studies SS.A.1.2.1: The student understands how individuals, ideas, decisions, and events can influence history. SS.B.2.2.4: The student understands how factors such as population growth, human migration, improved methods of transportation and communication, and economic development affect the use and conservation of natural resources. Science SC.G.1.2.2 The student knows that living things compete in a climatic region with other living things and that structural adaptations make them fit for an environment. National Science Education Standards: Content Standard C (K-4) - Characteristics of Organisms : Each plant or animal has different structures that serve different functions in growth, survival, and reproduction. For example, humans have distinct body structures for walking, holding, seeing, and talking. Content Standard C (5-8) - Diversity and adaptations of Organisms : Biological evolution accounts for the diversity of species developed through gradual processes over many generations. Species acquire many of their unique characteristics through biological adaptation, which involves the selection of naturally occurring variations in populations. Biological adaptations include changes in structures, behaviors, or physiology that enhance survival and reproductive success in a particular environment. -

Reviews of Recent Publications

Studies in 20th Century Literature Volume 19 Issue 2 Article 10 6-1-1995 Reviews of recent publications Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/sttcl Part of the French and Francophone Literature Commons, German Language and Literature Commons, Modern Literature Commons, and the Spanish and Portuguese Language and Literature Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation (1995) "Reviews of recent publications," Studies in 20th Century Literature: Vol. 19: Iss. 2, Article 10. https://doi.org/10.4148/2334-4415.1376 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in 20th Century Literature by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Reviews of recent publications Abstract Adelson, Leslie A. Making Bodies Making History: Feminism and German Identity by Sander L. Gilman Barrat, Barnaby B. Psychoanalysis and the Post-Modern Impulse: Knowing and Being Since Freud's Psychology by Mitchell Greenberg Calinescu, Matei. Rereading by Laurence M. Porter Donahue, Neil H. Forms of Disruption: Abstraction in Modern German Prose by Burton Pike Feminisms of the Belle Epoque, A Historical and Literary Anthology. Jennifer Waelti-Walters and Steven C. Hause, Eds. (Translated by Jette Kjaer, Lydia Willis, and Jennifer Waelti-Walters by Christiane J.P. Makward Hutchinson, Peter. Stefan Heym: The Perpetual Dissident by Susan M. Johnson Julien, Eileen. African Novels and the Question of Orality by Lifongo Vetinde Kristof, Agota. Le Troisième Mensonge by Jane Riles Laronde, Michel. -

Cognitive Adaptations of Social Bonding in Birds Nathan J

Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B (2007) 362, 489–505 doi:10.1098/rstb.2006.1991 Published online 24 January 2007 Cognitive adaptations of social bonding in birds Nathan J. Emery1,*, Amanda M. Seed2, Auguste M. P. von Bayern1 and Nicola S. Clayton2 1Sub-department of Animal Behaviour, University of Cambridge, Cambridge CB3 8AA, UK 2Department of Experimental Psychology, University of Cambridge, Cambridge CB2 3EB, UK The ‘social intelligence hypothesis’ was originally conceived to explain how primates may have evolved their superior intellect and large brains when compared with other animals. Although some birds such as corvids may be intellectually comparable to apes, the same relationship between sociality and brain size seen in primates has not been found for birds, possibly suggesting a role for other non-social factors. But bird sociality is different from primate sociality. Most monkeys and apes form stable groups, whereas most birds are monogamous, and only form large flocks outside of the breeding season. Some birds form lifelong pair bonds and these species tend to have the largest brains relative to body size. Some of these species are known for their intellectual abilities (e.g. corvids and parrots), while others are not (e.g. geese and albatrosses). Although socio-ecological factors may explain some of the differences in brain size and intelligence between corvids/parrots and geese/albatrosses, we predict that the type and quality of the bonded relationship is also critical. Indeed, we present empirical evidence that rook and jackdaw partnerships resemble primate and dolphin alliances. Although social interactions within a pair may seem simple on the surface, we argue that cognition may play an important role in the maintenance of long-term relationships, something we name as ‘relationship intelligence’. -

Telstar Satellite Rocket Launched

Today ' 3 i' ^^^^ ^ 21,950 lafad. Lej» tod|bt In the 4k, 9M' Weratr, page 2.' DIAL SH 1-0010 VOL. '85 NO 224. IMIM* itltr. MoniStT thronm frliUr. B^oond oitu Pwttf* rvu °3' «'-'• •"* raid at KM Buk and at ASditiooU XUllnc OtOei. RED BANK, N. J., TUESDAY, MAY 7, 1963 7c PER COPY PAGE ONE Senate to Probe Race) Tracks' Expenses TRENTON (AP)-The ttate sen- Hillery, R-Merris and Wayne Du- bill and that was why he support- the committee membership and Sandman on what basis the com- ate has deckled to do tome of moot, It-Warren, sponsored a ed Stamler's. < warned jokingly that any commit- mittee members were chosen. tee member caught with white- its own Investigating into a $2.4 measure calling for a similar In- "What he meant by not enough He said no committee member million expense account submit- vestigation, but their resolution votes for my bill is that he wash on his fingers would be bounced from the committee. could be running for re-election ted by two race tracks lor operat- did not include Cowgili and was couldn't get six votes in the GOP and have a race track in his caucus.. .there were 10 Demo- He-named Dumont as chairman ing a special 30-day season last limited to a senate committee of county. year to provide money for shore five, crats ready to vote for it here," and appointed Sens. Hillery; Stam- relief. Gives Reason Cowgili said. ler; waiiam F. Kelly, D-Hud- The only senator who,is run- The senate, after a heated ex- Sandman said on the senate floor As soon as the vote was tak- son, and John A. -

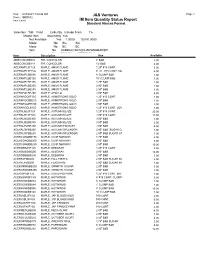

J&S Ventures IM Item Quantity Status Report

Run : 9/27/2021 7:20:46 AM J&S Ventures Page 1 Form : IMR0032 Item Level IM Item Quantity Status Report Standard Abecas Format Selection : Tab Field Order By Include From To Master Item Ascending Yes Net Available Yes 1.0000 10,000.0000 Mode No BG BG Mode No BC BC Item No HARBALCAR100 HARWEEBARSPI Item No ZZAVAIL ZZTRESTAK Item Description Size Available ABIECONCBB072 FIR, CONCOLOR 6' B&B 2.00 ABIECONCBB144 FIR, CONCOLOR 12' B&B 2.00 ACERAMFL0F125 MAPLE, AMUR FLAME 1.25" #15 CONT. 5.00 ACERAMFL0F15G MAPLE, AMUR FLAME 6' CL. #15 CONT. MULTI STEM 4.00 ACERAMFLBB096 MAPLE, AMUR FLAME 8' CLUMP B&B 1.00 ACERAMFLBB120 MAPLE, AMUR FLAME 10' CLUMP B&B 1.00 ACERAMFLBB175 MAPLE, AMUR FLAME 1.75" B&B 1.00 ACERAMFLBB200 MAPLE, AMUR FLAME 2.00" B&B 1.00 ACERAMFLBB250 MAPLE, AMUR FLAME 2.50" B&B 1.00 ACERAPOLBB200 MAPLE, APOLLO 2.00" B&B 5.00 ACERARGO0F125 MAPLE, ARMSTRONG GOLD 1.25" #15 CONT. 1.00 ACERARGOBB200 MAPLE, ARMSTRONG GOLD 2.00" B&B 1.00 ACERARGOBB250 MAPLE, ARMSTRONG GOLD 2.50" B&B 2.00 ACERARGOLB125 MAPLE, ARMSTRONG GOLD 1.25" #15 CONT. LOW BRANCH 1.00 ACERAUBL0F125 MAPLE, AUTUMN BLAZE 1.25" #15 CONT. 20.00 ACERAUBL0F20G MAPLE, AUTUMN BLAZE 2.00" #20 CONT. 17.00 ACERAUBLBB300 MAPLE, AUTUMN BLAZE 3.00" B&B 1.00 ACERAUBLBB350 MAPLE, AUTUMN BLAZE 3.50" B&B 2.00 ACERAUFABB200 MAPLE, AUTUMN FANTASY 2.00" B&B 4.00 ACERAUSPBB200 MAPLE, AUTUMN SPLENDOR 2.00" B&B SUGAR CADDO 1.00 ACERAUSPBB250 MAPLE, AUTUMN SPLENDOR 2.50" B&B SUGAR CADDO 1.00 ACERCONOBB175 MAPLE, CLNR NORWAY 1.75" B&B 2.00 ACERCONOBB200 MAPLE, CLNR NORWAY 2.00" B&B 5.00 ACERCONOBB250 MAPLE, CLNR NORWAY 2.50" B&B 19.00 ACERDEBO0F125 MAPLE, DEBORAH 1.25" #15 CONT. -

2011 Shelf-Registration Document

welcome ! Shelf-Registration Document 2011 Mercialys – 2011 Shelf-Registration Document 10, rue Cimarosa - 75016 Paris Tél. : +33 01 53 70 23 20 E-mail : [email protected] www.mercialys.com www.mercialys.com Shelf-Registration Document 2011 summary Summary 1. Business review (Financial statements for the year ended December 31, 2011) An excellent year in 2011: robust performance and growth throughout the year . 4 A year during which Mercialys stepped up its value creation strategy further . 4 A year confirming the solidity of Mercialys’s business model . 5 2. Financial report Financial statements . 7 Review of activity in 2011 and lease portfolio structure . 10 Review of consolidated results . 12 Subsequent events . 19 Outlook . 19 Review of the results of the parent Company, Mercialys SA . 20 Subsequent events following the Board of Directors meeting of February 9, 2012 that approved 2011 financial statement . 21 3. Portfolio and Valuation Portfolio valued at Euro 2,640 million at December 31, 2011 . 22 A diversified portfolio of retail assets . 24 Presence in areas with strong growth potential . 25 4. Stock market information Trading volume and share price over the last 18 months (source: Euronext Paris) . 31 Breakdown of share capital and voting rights at January 31, 2012 . 32 Crossing of share ownership thresholds . 32 Share buy‑back program . 33 Shareholders’ agreement . 35 Dividend policy . 36 Communication policy . 37 5. Corporate Governance Board of Directors and Executive Management . 38 Statutory Auditors . 56 Chairman’s Report . 58 Statutory Auditors’ report prepared in accordance with Article L 225. ‑235 of the French Commercial Code (“Code de commerce”), on the report prepared by the Chairman of the Board of Directors of Mercialys . -

Johannes Ulf Lange Kavli Institute for Particle Astrophysics and Cosmology [email protected], Johannesulf.Github.Io

Johannes Ulf Lange Kavli Institute for Particle Astrophysics and Cosmology [email protected], johannesulf.github.io RESEARCH INTERESTS Cosmology, Large-Scale Structure, Weak Gravitational Lensing, Galaxy-Halo Connection, Galaxy Formation Theory, Statistical Methods and Machine Learning EDUCATION Yale University 08/2014 – 08/2019 M.Sc., M.Phil, Ph.D. in Astronomy Thesis Advisor: Frank van den Bosch Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg 09/2012 – 08/2014 Master of Science in Physics Freie Universität Berlin 10/2009 – 08/2012 Bachelor of Science in Physics POSITIONS Kavli Institute for Particle Astrophysics and Cosmology 09/2021 – 08/2023 Stanford–Santa Cruz Cosmology Postdoctoral Fellow University of California, Santa Cruz 09/2019 – 08/2021 Stanford–Santa Cruz Cosmology Postdoctoral Fellow FIRST-AUTHOR PUBLICATIONS [10] J. U. Lange, A. P. Hearin, A. Leauthaud, F. C. van den Bosch, H. Guo, and J. DeRose. “Five-percent measurements of the growth rate from simulation-based mod- elling of redshift-space clustering in BOSS LOWZ”. arXiv e-prints, arXiv:2101.12261 (Jan. 2021), arXiv:2101.12261. [9] J. U. Lange, A. Leauthaud, S. Singh, H. Guo, R. Zhou, T. L. Smith, and F.-Y. Cyr- Racine. “On the halo-mass and radial scale dependence of the lensing is low effect”. MNRAS 502.2 (Apr. 2021), pp. 2074–2086. [8] J. U. Lange, F. C. van den Bosch, A. R. Zentner, K. Wang, A. P. Hearin, and H. Guo. “Cosmological Evidence Modelling: a new simulation-based approach to constrain cosmology on non-linear scales”. MNRAS 490.2 (Dec. 2019), pp. 1870–1878. [7] J. U. Lange, X. Yang, H. Guo, W. -

Botting Fred Wilson Scott Eds

The Bataille Reader Edited by Fred Botting and Scott Wilson • � Blackwell t..b Publishing Copyright © Blackwell Publishers Ltd, 1997 Introduction, apparatus, selection and arrangement copyright © Fred Botting and Scott Wilson 1997 First published 1997 2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 Blackwell Publishers Ltd 108 Cowley Road Oxford OX4 IJF UK Blackwell Publishers Inc. 350 Main Street Malden, MA 02 148 USA All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form Or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any fo rm of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Ubrary. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Bataille, Georges, 1897-1962. [Selections. English. 19971 The Bataille reader I edited by Fred Botting and Scott Wilson. p. cm. -(Blackwell readers) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-631-19958-6 (hc : alk. paper). -ISBN 0-631-19959-4 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Philosophy. 2. Criticism. I. Botting, Fred. -

Rattlesnake Tales 127

Hamell and Fox Rattlesnake Tales 127 Rattlesnake Tales George Hamell and William A. Fox Archaeological evidence from the Northeast and from selected Mississippian sites is presented and combined with ethnographic, historic and linguistic data to investigate the symbolic significance of the rattlesnake to northeastern Native groups. The authors argue that the rattlesnake is, chief and foremost, the pre-eminent shaman with a (gourd) medicine rattle attached to his tail. A strong and pervasive association of serpents, including rattlesnakes, with lightning and rainfall is argued to have resulted in a drought-related ceremo- nial expression among Ontario Iroquoians from circa A.D. 1200 -1450. The Rattlesnake and Associates Personified (Crotalus admanteus) rattlesnake man-being held a special fascination for the Northern Iroquoians Few, if any of the other-than-human kinds of (Figure 2). people that populate the mythical realities of the This is unexpected because the historic range of North American Indians are held in greater the eastern diamondback rattlesnake did not esteem than the rattlesnake man-being,1 a grand- extend northward into the homeland of the father, and the proto-typical shaman and warrior Northern Iroquoians. However, by the later sev- (Hamell 1979:Figures 17, 19-21; 1998:258, enteenth century, the historic range of the 264-266, 270-271; cf. Klauber 1972, II:1116- Northern Iroquoians and the Iroquois proper 1219) (Figure 1). Real humans and the other- extended southward into the homeland of the than-human kinds of people around them con- eastern diamondback rattlesnake. By this time the stitute a social world, a three-dimensional net- Seneca and other Iroquois had also incorporated work of kinsmen, governed by the rule of reci- and assimilated into their identities individuals procity and with the intensity of the reciprocity and families from throughout the Great Lakes correlated with the social, geographical, and region and southward into Virginia and the sometimes mythical distance between them Carolinas. -

Modificaciones En Factores Relacionados Con El Aroma Y La Textura De La Manzana, Melocotón Y Nectarina Durante La Maduración Y La Post- Cosecha

Modificaciones en factores relacionados con el aroma y la textura de la manzana, melocotón y nectarina durante la maduración y la post- cosecha Abel Ortiz Catalán R " Q $% R &' ' ()$ + , -.)/ " 1 2 - 234 $61Q&' ' ( )$ + ,R$ 6 $ Q $ % R 1 $ 2 ( , ) 1 + -7 8 9 8 92 - ) , ' 2 -.)/ 2 - 234 $&:;<< " " " # " "%& & " ' " % " % % ( '" * % & ! # # ! ! $ + , % & % & '! $ ! ( # $ ! $ & " ( &" -./ ) ' * !! 9 ! $Q, - R / 0, 12 3 4 5 $6/-73%(8 ' & ! 9) $Q:!;<=!>R / 0, 12 3 *1 9)9 ' $ ! ! %) ! $Q-2 R / 04 ,2 2, 12 3 ' ' / ! $ Q:!; ) <=!>R / 04 ,, 12 3 *112 9))> ' / 7 $ $ ! #! # >) Q, - R $ # ! / 04 ,, 12 3 *11 9 ' / / '! $Q- 2 R $ ! $ 0 ( 7 $ / 04 ,, 12 3 *112 9(9) ' / ? ! $ # $ ! ! # Q- 2 R / 04 ,, 12 22 3 ' ' / * Q7 # R $ ! & / 0, 12 24 ,2 3 *11 %)>( ' 3 @ $ ! ! $Q, - R / 04 ,, 12 3 *11 >((% ' 3 & ! # @ $ @ # $Q:!;<=!>R / 0, 12 3 *1 A ((%B; #((( ' ' 3 @ #! $ $ % Q? -

2011 Activity Report Mercialys – 2011 Activity Report Activity – 2011 Mercialys

welcome ! 2011 Activity Report Mercialys – 2011 Activity Report Activity – 2011 Mercialys 10, rue Cimarosa - 75016 Paris Tél. : +33 01 53 70 23 20 E-mail : [email protected] www.mercialys.com www.mercialys.com OUr GrOUP Profi le Chairman’s message .................... 2 Corporate Governance ............... 6 2011 Highlights ............................. 8 Key fi gures ................................... 10 OUr ValUes Making you feel at home The Esprit Voisin concept: Mercialys’s trademark ....................................... 14 Refl ecting local identity ..................................... 16 Useful ideas ......................................................... 18 Shopping centers in line with their customers ........................................... 20 Responsible retailers and citizens .................. 22 OUr aiM A new way of looking at retail Valentine Grand Centre shopping center: a story shared with the people of Marseille ............... 26 “Esprit Voisin“ concept at the heart of... ....................... 32 Partnerships creating value ............................................... 37 The art of transformation .................................................. 39 Entrepreneurial spirit .......................................................... 40 2006-11: the Alcudia years ............................................ 42 2012: The “Foncière Commerçante” strategy .............. 43 In 2012, they will also adopt the “Esprit Voisin” concept... ............................................ 44 OUR GROUP MERCIALYS Activity Report -

The Teaching of Russian Culture to Americans: Contemporary Values

71t .7487 JARVIS, Donald Karl, 1939- THE TEACHING OF RUSSIAN CULTURE TO AMERICANS; CONTEMPORARY VALUES AND NORMS. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1970 Education, general University Microfilms, A XEROX Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan © Copyright by Donald Karl Jarvis 1971 THIS DISSERTATION HAS BEEN MICROFILMED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED THE TEACHING OP RUSSIAN CULTURE TO AMERICANS: CONTEMPORARY VALUES AND NORMS DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Donald Karl Jarvis, B.A. ***** The Ohio State University 1970 Approved by Adviser Department of Foreign Language Education ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The writer wishes to express appreciation to Professor Douglas Card of the Department of Sociology, The Ohio State University, for his interested assistance in siiggesting sources and evaluating the content of Chapter II. Gratitude is also due the reading committee, Professors Edward D. Allen, M. Eugene Gilliora, and Ronald E. Smith for their assistance in locating materials and their wise advice. Professor Smith's support was exceptionally strong throughout the project. Finally, the writer is indebted to his wife, Janelle Jamison Jarvis, for her continued support in this project, for her typing and editing of the manuscript, and for her valuable suggestions on Chapter IV. ii VITA April 6, 1939 . Born - Ithaca, New York 1964 .............. B.A., Brigham Young Univer sity , Provo, Utah 1964-1965 .......... Teaching Assistant, Depart ment of Foreign Languages, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah 1965-1966 .......... Teacher of Russian, German, and Mathematics, Beaver High School, Beaver, Utah 1966-1967 .......... Teacher of Russian and United States History, East High School, Salt Lake City, Utah 1967-1970 .....