The Foreign Policy of Park Chunghee: 1968- 1979 Lyong Choi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

6/06 Neoliberalism and the Gwangju Uprising

8/1/2020 Neoliberalism and the Gwangju Uprising Neoliberalism and the Gwangju Uprising By Georgy Katsiaficas Abstract Drawing from US Embassy documents, World Bank statistics, and memoirs of former US Ambassador Gleysteen and Commanding General Wickham, US actions during Chun Doo Hwan’s first months in power are examined. The Embassy’s chief concern in this period was liberalization of the Korean economy and securing US bankers’ continuing investments. Political liberalization was rejected as an appropriate goal, thereby strengthening Korean anti-Americanism. The timing of economic reforms and US support for Chun indicate that the suppression of the Gwangju Uprising made possible the rapid imposition of the neoliberal accumulation regime in the ROK. With the long-term success of increasing American returns on investments, serious strains are placed on the US/ROK alliance. South Korean Anti-Americanism Anti-Americanism in South Korea remains a significant problem, one that simply won’t disappear. As late as 1980, the vast majority of South Koreans believed the United States was a great friend and would help them achieve democracy. During the Gwangju Uprising, the point of genesis of contemporary anti-Americanism, a rumor that was widely believed had the aircraft carrier USS Coal Sea entering Korean waters to aid the insurgents against Chun Doo Hwan and the new military dictatorship. Once it became apparent that the US had supported Chun and encouraged the new military authorities to suppress the uprising (even requesting that they delay the re-entry of troops into the city until after the Coral Sea had arrived), anti-Americanism in South Korea emerged with startling rapidity and unexpected longevity. -

Record of North Korea's Major Conventional Provocations Since

May 25, 2010 Record of North Korea’s Major Conventional Provocations since 1960s Complied by the Office of the Korea Chair, CSIS Please note that the conventional provocations we listed herein only include major armed conflicts, military/espionage incursions, border infractions, acts of terrorism including sabotage bombings and political assassinations since the 1960s that resulted in casualties in order to analyze the significance of the attack on the Cheonan and loss of military personnel. This list excludes any North Korean verbal threats and instigation, kidnapping as well as the country’s missile launches and nuclear tests. January 21, 1968 Blue House Raid A North Korean armed guerrilla unit crossed the Demilitarized Zone into South Korea and, in disguise of South Korean military and civilians, attempted to infiltrate the Blue House to assassinate South Korean President Park Chung-hee. The assassination attempt was foiled, and in the process of pursuing commandos escaping back to North Korea, a significant number of South Korean police and soldiers were killed and wounded, allegedly as many as 68 and 66, respectively. Six American casualties were also reported. ROK Response: All 31 North Korean infiltrators were hunted down and killed except Kim Shin-Jo. After the raid, South Korea swiftly moved to strengthen the national defense by establishing the ROK Reserve Forces and defense industry and installing iron fencing along the military demarcation line. January 23, 1968 USS Pueblo Seizure The U.S. navy intelligence ship Pueblo on its mission near the coast of North Korea was captured in international waters by North Korea. Out of 83 crewmen, one died and 82 men were held prisoners for 11 months. -

DIRECTING the Disorder the CFR Is the Deep State Powerhouse Undoing and Remaking Our World

DEEP STATE DIRECTING THE Disorder The CFR is the Deep State powerhouse undoing and remaking our world. 2 by William F. Jasper The nationalist vs. globalist conflict is not merely an he whole world has gone insane ideological struggle between shadowy, unidentifiable and the lunatics are in charge of T the asylum. At least it looks that forces; it is a struggle with organized globalists who have way to any rational person surveying the very real, identifiable, powerful organizations and networks escalating revolutions that have engulfed the planet in the year 2020. The revolu- operating incessantly to undermine and subvert our tions to which we refer are the COVID- constitutional Republic and our Christian-style civilization. 19 revolution and the Black Lives Matter revolution, which, combined, are wreak- ing unprecedented havoc and destruction — political, social, economic, moral, and spiritual — worldwide. As we will show, these two seemingly unrelated upheavals are very closely tied together, and are but the latest and most profound manifesta- tions of a global revolutionary transfor- mation that has been under way for many years. Both of these revolutions are being stoked and orchestrated by elitist forces that intend to unmake the United States of America and extinguish liberty as we know it everywhere. In his famous “Lectures on the French Revolution,” delivered at Cambridge University between 1895 and 1899, the distinguished British historian and states- man John Emerich Dalberg, more com- monly known as Lord Acton, noted: “The appalling thing in the French Revolution is not the tumult, but the design. Through all the fire and smoke we perceive the evidence of calculating organization. -

Electoral Politics in South Korea

South Korea: Aurel Croissant Electoral Politics in South Korea Aurel Croissant Introduction In December 1997, South Korean democracy faced the fifteenth presidential elections since the Republic of Korea became independent in August 1948. For the first time in almost 50 years, elections led to a take-over of power by the opposition. Simultaneously, the election marked the tenth anniversary of Korean democracy, which successfully passed its first ‘turnover test’ (Huntington, 1991) when elected President Kim Dae-jung was inaugurated on 25 February 1998. For South Korea, which had had six constitutions in only five decades and in which no president had left office peacefully before democratization took place in 1987, the last 15 years have marked a period of unprecedented democratic continuity and political stability. Because of this, some observers already call South Korea ‘the most powerful democracy in East Asia after Japan’ (Diamond and Shin, 2000: 1). The victory of the opposition over the party in power and, above all, the turnover of the presidency in 1998 seem to indicate that Korean democracy is on the road to full consolidation (Diamond and Shin, 2000: 3). This chapter will focus on the role elections and the electoral system have played in the political development of South Korea since independence, and especially after democratization in 1987-88. Five questions structure the analysis: 1. How has the electoral system developed in South Korea since independence in 1948? 2. What functions have elections and electoral systems had in South Korea during the last five decades? 3. What have been the patterns of electoral politics and electoral reform in South Korea? 4. -

Korean Nova Records in A.D. 1073 and A.D. 1074: R Aquarii

A&A 435, 207–214 (2005) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361:20042455 & c ESO 2005 Astrophysics Korean nova records in A.D. 1073 and A.D. 1074: R Aquarii Hong-Jin Yang1, Myeong-Gu Park2, Se-Hyung Cho1, and Changbom Park3 1 Korea Astronomy and Space Science Institute, 61-1 Hwaam, Yuseong, Daejeon 305-348, Korea e-mail: [hjyang;cho]@kasi.re.kr 2 Department of Astronomy and Atmospheric Sciences, Kyungpook National University, Daegu 702-701, Korea e-mail: [email protected] 3 School of Physics, Korea Institute for Advanced Study, Seoul 130-722, Korea e-mail: [email protected] Received 30 November 2004 / Accepted 31 December 2004 Abstract. R Aqr is known to be a symbiotic binary system with an associated extended emission nebula, possibly produced by a historic outburst. To find the associated historic records, we searched for and compiled all Guest Star and Peculiar Star records in three Korean official history books that cover almost two thousand years, Samguksagi, Goryeosa, Joseonwangjosillok. In addition to the record of A.D. 1073, previously noted by Li (1985, Chin. Astron. Astrophys., 9, 322), we have found in Goryeosa another candidate record of A.D. 1074, which has the same positional description as that of A.D. 1073 with an additional brightness description. We examined various aspects of the two records and conclude that they both are likely to be the records of outburst of R Aqr. This means that there were two successive outbursts in A.D. 1073 and in A.D. 1074, separated by approximately one year. -

In Pueblo's Wake

IN PUEBLO’S WAKE: FLAWED LEADERSHIP AND THE ROLE OF JUCHE IN THE CAPTURE OF THE USS PUEBLO by JAMES A. DUERMEYER Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Arlington in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN U.S. HISTORY THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT ARLINGTON December 2016 Copyright © by James Duermeyer 2016 All Rights Reserved Acknowledgements My sincere thanks to my professor and friend, Dr. Joyce Goldberg, who has guided me in my search for the detailed and obscure facts that make a thesis more interesting to read and scholarly in content. Her advice has helped me to dig just a bit deeper than my original ideas and produce a more professional paper. Thank you, Dr. Goldberg. I also wish to thank my wife, Janet, for her patience, her editing, and sage advice. She has always been extremely supportive in my quest for the masters degree and was my source of encouragement through three years of study. Thank you, Janet. October 21, 2016 ii Abstract IN PUEBLO’S WAKE: FLAWED LEADERSHIP AND THE ROLE OF JUCHE IN THE CAPTURE OF THE USS PUEBLO James Duermeyer, MA, U.S. History The University of Texas at Arlington, 2016 Supervising Professor: Joyce Goldberg On January 23, 1968, North Korea attacked and seized an American Navy spy ship, the USS Pueblo. In the process, one American sailor was mortally wounded and another ten crew members were injured, including the ship’s commanding officer. The crew was held for eleven months in a North Korea prison. -

July 1979 • Volume Iv • Number Vi

THE FASTEST GROWING CHURCH IN THE WORLD by Brother Keith E. L'Hommedieu, D.D. quite safe tosay that ofall the organized religious sects on the current scene, one church in particular stands above all in its unique approach to religion. The Universal LifeChurch is the onlyorganized church in the world withno traditional religious doctrine. Inthe words of Kirby J. Hensley,founder, "The ULC only believes in what is right, and that all people have the right to determine what beliefs are for them, as long as Brother L 'Hommed,eu 5 Cfla,r,nan right ol the Board of Trusteesof the Sa- they do not interferewith the rights ofothers.' cerdotal Orderof the Un,versalL,fe andserves on the Board of O,rec- Reverend Hensley is the leader ofthe worldwide torsOf tOe fnternahOna/ Uns'ersaf Universal Life Church with a membership now L,feChurch, Inc. exceeding 7 million ordained ministers of all religious bileas well as payfor traveland educational expenses. beliefs. Reverend Hensleystarted the church in his NOne ofthese expenses are reported as income to garage by ordaining ministers by mail. During the the IRS. Recently a whole town in Hardenburg. New 1960's, he traveled all across the country appearing York became Universal Life ministers and turned at college rallies held in his honor where he would their homes into religious retreatsand monasteries perform massordinations of thousands of people at a thereby relieving themselves of property taxes, at time. These new ministers were then exempt from least until the state tries to figure out what to do. being inducted into the armed forces during the Churches enjoycertain othertax benefits over the undeclared Vietnam war. -

S" Qe Ay% ~ ~O&A Yo, 1O Q1 B5

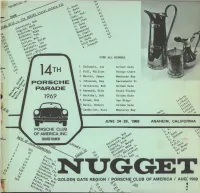

41 6 ~ @ete Ge Qe +~~ sts' seta ~o oe~ G' Octo Qe ~/Sf coot ~Qe ~ Cpa Oe ~aa ~ +eea sob y 0 Oe St ~eai Ge CP goe ~ea s" Qe ay% ~ ~o&a yO, 1O Q1 b5 yO Reitmeir, Joe Golden Gate ~4$ TH 2 Roll, William Grange Coas t 3 Masinl& James Monterey Bay 4 PORSCHE 4 Johansen, Ray Sacramento Vz 5 Garretson, Bob Golden Gate PARADE 6 Raymond, Dick Great Plains , ~ epee Wo~ 1969 Buckthal, Bob Golden Gate 8 Brown, Bob San Diego 9 Daves, Robert Golden Gate Sandholdt~ Pete Monterey Bay w~ 1o~ on JUMf 24-28, 1969 ANANf IIN, CALIFORNA PORSCHE eve v OF AMERICA We. ~o ~e 555K MNR 0 9 Oa oo eS g', 0 op yQ ae3 6J Oe p~ eel~ ie~ dO 6d ldG ~e e„, Jest, 'J. @~o GOLDEN GATE RE/ION / PORSCHE ClUS OF:AMERICA / Ale 0- -i This Noath~s nesting features the Rouse Specialty dinner «t KONNA ~ The barbequod Now Torh strip steak is fsnous for at least a nile md a half in all directions~ snd the Nsklava, that waits in your nouch, hem authentic Creek dessert Creat Chat you wiH especially reaeaher. After the dinner «esting you will wsnt Co stay for the late show in the lounge with dancing snd music haportsd d~y froms Athena, Ie en reservations (wo have roon for at least RSC), but dsn~t be late getting ~yours in; this dinner you wcn't want Co miss. N~EU XORNA Specialty Ssla4 New York Steah RSSO sa ssmccw AVDNK ~ SAM JOSE Sarboqued Strip Pheea: 20$-HBk Bshed potato «ith Sour Croaa Vegetable proach Nroad Nahlava ~Ok: Saturday Fling, August 9 QIBRMR: 'y:00 p n. -

A Sociocultural Analysis of Korean Sport for International Development Initiatives

A Sociocultural Analysis of Korean Sport for International Development Initiatives Dongkyu Na Thesis submitted to the University of Ottawa in partial Fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Human Kinetics School of Human Kinetics Faculty of Health Sciences University of Ottawa © Dongkyu Na, Ottawa, Canada, 2021 Korean Sport for International Development ii Abstract This dissertation focuses on the following questions: 1) What is the structure of the Korean sport for international development discourse? 2) How are the historical transformations of particular rules of formation manifested in the discourse of Korean sport for international development? 3) What knowledge, ideas, and strategies make up Korean sport for international development? And 4) what are the ways in which these components interact with the institutional aspirations of the Korean government, directed by the official development assistance goals, the foreign policy and diplomatic agenda, and domestic politics? To address these research questions, I focus my analysis on the Korea International Cooperation Agency (KOICA) and its 30 years of expertise in designing and implementing sport and physical activity–related programs and aid projects. For this research project, I collected eight different sets of KOICA documents published from 1991 to 2017 as primary sources and two different sets of supplementary documents including government policy documents and newspaper articles. By using Foucault’s archaeology and genealogy as methodological -

Courts' Hostile Treatment of Site-Specific Works Under Vara

DePaul Journal of Art, Technology & Intellectual Property Law Volume 20 Issue 1 Fall 2009 Article 7 Hardly a Walk in the Park: Courts' Hostile Treatment of Site- Specific orksW under VARA Virginia M. Cascio Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/jatip Recommended Citation Virginia M. Cascio, Hardly a Walk in the Park: Courts' Hostile Treatment of Site-Specific orksW under VARA, 20 DePaul J. Art, Tech. & Intell. Prop. L. 167 (2009) Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/jatip/vol20/iss1/7 This Case Notes and Comments is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Law at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in DePaul Journal of Art, Technology & Intellectual Property Law by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cascio: Hardly a Walk in the Park: Courts' Hostile Treatment of Site-Spec HARDLY A WALK IN THE PARK: COURTS' HOSTILE TREATMENT OF SITE-SPECIFIC WORKS UNDER VARA "Men do change, and change comes like a little wind that ruffles the curtains at dawn, and it comes like the stealthy perfume of wildflowers hidden in the grass."--John Steinbeck1 I. INTRODUCTION As you walk through Grant Park on your way to downtown Chicago, you enjoy the ordered, natural splendor of two beautiful elliptical fields of wildflowers.2 The pleasure is further amplified by the seasonal transformation of nature's palette that brings forth a kaleidoscope of colors and patterns as new flowers emerge and older ones fade.3 Now, after twenty years of enjoying this park, one day you discover that sixty percent of the flowers have been destroyed, and those remaining have been abandoned to grow without care.' Imagine the feelings of the artist who created this living canvas when witnessing the culmination of his life's work destroyed by the Chicago Park District without notice after twenty 1. -

INDO 50 0 1106971426 29 60.Pdf (1.608Mb)

A m e r ic a n " L o w P o s t u r e " P o l ic y t o w a r d In d o n e s ia in t h e M o n t h s L e a d in g u p t o t h e 1965 "C o u p " 1 Frederick Bunnell Introduction This article seeks to contribute to the reconstruction, explanation, and evaluation of the Johnson Administration's response to President Sukarno's radicalization of Indonesia's do mestic politics and foreign policy in the first nine months of 1965 leading up to the abortive "coup" on October 1,1965. The focus throughout is on both the thinking and the politics of what can be termed "the 1965 Indonesia policy group."2 That unofficial group was the informal constellation of US officials both in Indonesia (in the Embassy-based country team)3 and in Washington (in the *This article has enjoyed a long, troubled odyssey. Growing out of intermittent research on American-Indonesian relations dating back to my doctoral dissertation field research in Jakarta in 1963-1965, the substance of the article, including its primary conclusions, was presented in papers at the August 1979 Indonesian Studies Con ference in Berkeley and the March 1980 International Studies Association Conference in Los Angeles. I am in debted to the American Philosophical Society, the Lyndon Baines Johnson Foundation, and the Vassar College Faculty Research Committee for grants in 1976-1979 which facilitated the brunt of the archival and interview re search undergirding the article. -

![Arxiv:2104.05964V3 [Cs.CL] 7 May 2021 1 Introduction Discover the Important Historical Events Over the Last Hundreds of Years](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1821/arxiv-2104-05964v3-cs-cl-7-may-2021-1-introduction-discover-the-important-historical-events-over-the-last-hundreds-of-years-851821.webp)

Arxiv:2104.05964V3 [Cs.CL] 7 May 2021 1 Introduction Discover the Important Historical Events Over the Last Hundreds of Years

Restoring and Mining the Records of the Joseon Dynasty via Neural Language Modeling and Machine Translation Kyeongpil Kang Kyohoon Jin Soyoung Yang Scatter Lab Chung-Ang University KAIST Seoul, South Korea Seoul, South Korea Daejeon, South Korea [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Soojin Jang Jaegul Choo Youngbin Kim Chung-Ang University KAIST Chung-Ang University Seoul, South Korea Daejeon, South Korea Seoul, South Korea [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Abstract records in a digital form for long-term preservation. A representative example is the Google Books Li- Understanding voluminous historical records brary Project1. However, despite the importance of provides clues on the past in various aspects, such as social and political issues and even the historical records, it has been challenging to natural science facts. However, it is generally properly utilize the records for the following rea- difficult to fully utilize the historical records, sons. First, the nontrivial amounts of the documents since most of the documents are not written are partially damaged and unrecognizable due to in a modern language and part of the contents unfortunate historical events or environments, such are damaged over time. As a result, restoring as wars and disasters, as well as the weak durability the damaged or unrecognizable parts as well as of paper documents. These factors result in difficul- translating the records into modern languages are crucial tasks. In response, we present a ties to translate and understand the records. Second, multi-task learning approach to restore and as most of the records are written in ancient and out- translate historical documents based on a self- dated languages, non-experts are difficult to read attention mechanism, specifically utilizing two and understand them.