From Cultural Heritage to the Confederacy Maliha Ikram

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2018 MOREHEAD-CAIN ALUMNI FORUM Schedule of Events

2018 MOREHEAD-CAIN ALUMNI FORUM Schedule of Events FRIDAY, OCTOBER 19 12:00–5:00 p.m. | Forum Registration | Morehead-Cain Offices Check in, pick up your registration packet, and enjoy some refreshments while you catch up with current scholars and fellow alumni. Visit the Morehead-Cain Gallery in the hallway off the main lobby to take in an exhibition of Morehead-Cain Scholar photography specially curated for Forum visitors. 2:00–2:45 p.m. | Lecture by a Favorite Professor | Hanes Art Center Auditorium Enjoy the opportunity to return to college (but without the papers and exams)! This lively lecture and discussion with a wildly popular Carolina professor is sure to stimulate the brain cells and bring us all back to our Carolina days. Zeynep Tufekci is an associate professor in the School of Information and Library Science and an adjunct professor in the School of Sociology at UNC-Chapel Hill. She is also a faculty associate with Harvard’s Berkman Klein Center for Internet and Society. Professor Tufekci is a Turkish writer, academic, and techno-sociologist known primarily for her research on the social implications of emerging technologies in the context of politics and corporate responsibility. 2:45–3:15 p.m. | Panelist and Speaker Organizational Meeting | Hanes Art Center Auditorium All Forum speakers and panelists are invited to a brief organizational meeting immediately following the lecture. Meet your fellow speakers and panelists and receive logistical and other instructions for a successful weekend! 3:00–6:30 p.m. | Free Time Free-time suggestions: • 3:00 p.m. -

Mccorkle PLACE

CHAPTER EIGHT: McCORKLE PLACE McCorkle Place is said to be the most densely memorialized piece of real estate in North Carolina.501 On the University’s symbolic front lawn, there are almost a dozen monuments and memorials fundamental to the University’s lore and traditions, but only two monuments within the space have determined the role of McCorkle Place as a space for racial justice movements.502 The Unsung Founders Memorial and the University’s Confederate Monument were erected on the oldest quad of the campus almost a century apart for dramatically different memorial purposes. The former honors the enslaved and freed Black persons who “helped build” the University, while the latter commemorated, until its toppling in August 2018, “the sons of the University who entered the war of 1861-65.”503 Separated by only a few dozen yards, the physical distinctions between the two monuments were, before the Confederate Monument was toppled, quite striking. The Unsung 501 Johnathan Michels, “Who Gets to be Remembered In Chapel Hill?,” Scalawag Magazine, 8 October 2016, <https://www.scalawagmagazine.org/2016/10/whats-in-a-name/>. 502 Timothy J. McMillan, “Remembering Forgetting: A Monument to Erasure at the University of North Carolina,” in Silence, Screen and Spectacle: Rethinking Social Memory in the Age of Information, ed. Lindsay A. Freeman, Benjamin Nienass, and Rachel Daniell, 137-162, (Berghahn Book: New York, New York, 2004): 139-142; Other memorials and sites of memory within McCorkle Place include the Old Well, the Davie Poplar, Old East, the Caldwell Monument, a Memorial to Founding Trustees, and the Speaker Ban Monument. -

For Controversial NAS, All's Quiet on the National Front

WELCOME BACK ALUMNI •:- •:• -•:•••. ;:: Holy war THE CHRONICLE theo FRIDAY. NOVEMBER 2, 1990 DUKE UNIVERSITY DURHAM, NORTH CAROLINA Huge pool of candidates Budget crunch threatens jazz institute leaves Pearcy concerned Monk center on hold for now r- ————. By JULIE MEWHORT From staff reports Ronald Krifcher, Brian Ladd, performing and non-performing An exceptionally large can David Rollins and Steven The creation ofthe world's first classes in jazz. didate pool for the ASDU Wild, Trinity juniors Sam conservatory for jazz music is on The Durham city and county presidency has President Con Bell, Marc Braswell, Mandeep hold for now. governments have already pur nie Pearcy skeptical of the in Dhillon, Eric Feddern, Greg During the budgeting process chased land for the institute at tentions of several of the can Holcombe, Kirk Leibert, Rich this summer, the North Carolina the intersection of Foster and didates. Pierce, Tonya Robinson, Ran General Assembly was forced to Morgan streets, but officials do Twenty-five people com dall Skrabonja and Heyward cut funding for an indefinite not have funds to begin actual pleted declaration forms Wall, Engineering juniors period to the Thelonious Monk construction. before yesterday's deadline. Chris Hunt and Howard Institute. "Our response is to recognize Last year only four students Mora, Trinity sophomores The institute, a Washington- that the state has several finan ran for the office. James Angelo, Richard Brad based organization, has been cial problems right now. We just Pearcy said she and other ley, Colin Curvey, Rich Sand planning to build a music conser have to continue hoping that the members of the Executive ers and Jeffrey Skinner and vatory honoring in downtown budget will improve," said Committee are trying to de Engineering sophomores Durham. -

German Jews in the United States: a Guide to Archival Collections

GERMAN HISTORICAL INSTITUTE,WASHINGTON,DC REFERENCE GUIDE 24 GERMAN JEWS IN THE UNITED STATES: AGUIDE TO ARCHIVAL COLLECTIONS Contents INTRODUCTION &ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 1 ABOUT THE EDITOR 6 ARCHIVAL COLLECTIONS (arranged alphabetically by state and then city) ALABAMA Montgomery 1. Alabama Department of Archives and History ................................ 7 ARIZONA Phoenix 2. Arizona Jewish Historical Society ........................................................ 8 ARKANSAS Little Rock 3. Arkansas History Commission and State Archives .......................... 9 CALIFORNIA Berkeley 4. University of California, Berkeley: Bancroft Library, Archives .................................................................................................. 10 5. Judah L. Mages Museum: Western Jewish History Center ........... 14 Beverly Hills 6. Acad. of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences: Margaret Herrick Library, Special Coll. ............................................................................ 16 Davis 7. University of California at Davis: Shields Library, Special Collections and Archives ..................................................................... 16 Long Beach 8. California State Library, Long Beach: Special Collections ............. 17 Los Angeles 9. John F. Kennedy Memorial Library: Special Collections ...............18 10. UCLA Film and Television Archive .................................................. 18 11. USC: Doheny Memorial Library, Lion Feuchtwanger Archive ................................................................................................... -

S" Qe Ay% ~ ~O&A Yo, 1O Q1 B5

41 6 ~ @ete Ge Qe +~~ sts' seta ~o oe~ G' Octo Qe ~/Sf coot ~Qe ~ Cpa Oe ~aa ~ +eea sob y 0 Oe St ~eai Ge CP goe ~ea s" Qe ay% ~ ~o&a yO, 1O Q1 b5 yO Reitmeir, Joe Golden Gate ~4$ TH 2 Roll, William Grange Coas t 3 Masinl& James Monterey Bay 4 PORSCHE 4 Johansen, Ray Sacramento Vz 5 Garretson, Bob Golden Gate PARADE 6 Raymond, Dick Great Plains , ~ epee Wo~ 1969 Buckthal, Bob Golden Gate 8 Brown, Bob San Diego 9 Daves, Robert Golden Gate Sandholdt~ Pete Monterey Bay w~ 1o~ on JUMf 24-28, 1969 ANANf IIN, CALIFORNA PORSCHE eve v OF AMERICA We. ~o ~e 555K MNR 0 9 Oa oo eS g', 0 op yQ ae3 6J Oe p~ eel~ ie~ dO 6d ldG ~e e„, Jest, 'J. @~o GOLDEN GATE RE/ION / PORSCHE ClUS OF:AMERICA / Ale 0- -i This Noath~s nesting features the Rouse Specialty dinner «t KONNA ~ The barbequod Now Torh strip steak is fsnous for at least a nile md a half in all directions~ snd the Nsklava, that waits in your nouch, hem authentic Creek dessert Creat Chat you wiH especially reaeaher. After the dinner «esting you will wsnt Co stay for the late show in the lounge with dancing snd music haportsd d~y froms Athena, Ie en reservations (wo have roon for at least RSC), but dsn~t be late getting ~yours in; this dinner you wcn't want Co miss. N~EU XORNA Specialty Ssla4 New York Steah RSSO sa ssmccw AVDNK ~ SAM JOSE Sarboqued Strip Pheea: 20$-HBk Bshed potato «ith Sour Croaa Vegetable proach Nroad Nahlava ~Ok: Saturday Fling, August 9 QIBRMR: 'y:00 p n. -

How the Silent Sam Lawsuit Unraveled by Maeve Sheehey the N.C

August, 2018 Carol Folt announced her resignation and authorized the removal of Silent Sam’s pedestal. November, 2019 Judge Allen Baddour ruled to vacate the judgement and dismiss the lawsuit. DTH/TARYN REVOIR Protesters toppled the monument the day before classes began in August 2018. DTH/EMILY CAROLINE SARTIN January, 2019 PHOTO COURTESY OF SCV MEMBERS Kevin Stone, commander of the N.C. Sons of Confederate Veterans, stood with the statue after suing for possession of Silent Sam. DTH/MAYA CARTER February, 2020 DTH/CRISAUN HARDY How the Silent Sam lawsuit unraveled By Maeve Sheehey the N.C. SCV, calling the settlement with the settlement. In the letter, he Dec. 16, 2020 — Rand called were politically active during the University Editor deal a strategic victory. Stone talked emphasized that the trust could only the legal motion by the Lawyers’ Civil Rights Movement, submitted about private meetings between the be used for the monument’s care Committee for Civil Rights Under an amicus brief in favor of reversing Nov. 21, 2019 — The Sons of SCV leadership, lawyers and BOG and preservation. Law professor Eric Law irresponsible. the Silent Sam settlement. Confederate Veterans received members before the suit was filed Muller said this was false information, News outlets found out about the $74,999 in a settlement with the and settled on Nov. 27. since the trust could also be used for a first SCV settlement on Dec. 16. Jan 30, 2020 — Though the Board of Governors. It stated that the building to house the monument. Nov. 21 settlement agreement did SCV would not display Confederate Dec. -

Recommendation for the Disposition and Preservation of the Confederate Monument

Recommendation for the Disposition and Preservation of the Confederate Monument A Four-Part Plan presented by UNC-Chapel Hill to the UNC Board of Governors Appendices TABLE OF CONTENTS A-1: Executive Summary of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Public Safety Panel Report. ..................... 3 A-2: Summary of Safety and Security Considerations ......... 6 B: Letter from the North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources ................................... 10 C: Campus Map ................................................................. 11 D: Legal Considerations ..................................................... 12 E: Requested Cost Estimates .............................................15 F: Work of the Chancellor’s Task Force on UNC Chapel Hill History ...........................................28 G-1: Site Evaluation ........................................................... 31 G-2: Summary of Possible Sites for Disposition of Confederate Monument ......................... 38 H: Summary of Community and Public Input ..................... 52 Appendix A-1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA AT CHAPEL HILL PUBLIC SAFETY PANEL REPORT This is an executive summary of the Report of a five-person expert Panel (the “Panel”) convened by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (“UNC-CH”) to assess the security and public safety issues associated with the “Silent Sam” civil war monument (the “Monument”). This Panel consisted of five security professionals led by Chris Swecker, Attorney at Law and former FBI Assistant Director. Other members include Jane Perlov, who has served as NYPD Chief of Detectives, Queens, Secretary of Public Safety, Commonwealth of Mass. and Chief of Police in Raleigh N.C.; Louis Quijas, former FBI Assistant Director and Chief of Police, High Point, N.C.; Johnny Jennings, Deputy Chief of Police, Charlotte Mecklenburg Police Department (CMPD); and Edward Reeder, Major General US Army Special Forces Command (Ret.) and CEO of Five Star Global Security. -

Courts' Hostile Treatment of Site-Specific Works Under Vara

DePaul Journal of Art, Technology & Intellectual Property Law Volume 20 Issue 1 Fall 2009 Article 7 Hardly a Walk in the Park: Courts' Hostile Treatment of Site- Specific orksW under VARA Virginia M. Cascio Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/jatip Recommended Citation Virginia M. Cascio, Hardly a Walk in the Park: Courts' Hostile Treatment of Site-Specific orksW under VARA, 20 DePaul J. Art, Tech. & Intell. Prop. L. 167 (2009) Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/jatip/vol20/iss1/7 This Case Notes and Comments is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Law at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in DePaul Journal of Art, Technology & Intellectual Property Law by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cascio: Hardly a Walk in the Park: Courts' Hostile Treatment of Site-Spec HARDLY A WALK IN THE PARK: COURTS' HOSTILE TREATMENT OF SITE-SPECIFIC WORKS UNDER VARA "Men do change, and change comes like a little wind that ruffles the curtains at dawn, and it comes like the stealthy perfume of wildflowers hidden in the grass."--John Steinbeck1 I. INTRODUCTION As you walk through Grant Park on your way to downtown Chicago, you enjoy the ordered, natural splendor of two beautiful elliptical fields of wildflowers.2 The pleasure is further amplified by the seasonal transformation of nature's palette that brings forth a kaleidoscope of colors and patterns as new flowers emerge and older ones fade.3 Now, after twenty years of enjoying this park, one day you discover that sixty percent of the flowers have been destroyed, and those remaining have been abandoned to grow without care.' Imagine the feelings of the artist who created this living canvas when witnessing the culmination of his life's work destroyed by the Chicago Park District without notice after twenty 1. -

02-22-2021 Through 02-28-2021

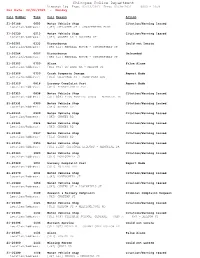

Chicopee Police Department Dispatch Log From: 02/22/2021 Thru: 02/28/2021 0000 - 2359 For Date: 02/22/2021 - Monday Call Number Time Call Reason Action 21-20188 0052 Motor Vehicle Stop Citation/Warning Issued Location/Address: [CHI] CHICOPEE ST + CHARPENTIER BLVD 21-20230 0215 Motor Vehicle Stop Citation/Warning Issued Location/Address: [CHI] GRANBY RD + COLUMBA ST 21-20261 0333 Disturbance Could not Locate Location/Address: [CHI 612] KENDALL HOUSE - SPRINGFIELD ST 21-20284 0607 Disturbance Unfounded Location/Address: [CHI 612] KENDALL HOUSE - SPRINGFIELD ST 21-20305 0750 Alarm False Alarm Location/Address: [CHI 931] TD BANK NA - MEADOW ST 21-20306 0750 Crash Property Damage Report Made Location/Address: [CHI] CHICOPEE ST + SHAW PARK AVE 21-20319 0818 Larceny Complaint Past Report Made Location/Address: [CHI] PENNSYLVANIA AVE 21-20325 0838 Motor Vehicle Stop Citation/Warning Issued Location/Address: [CHI 958] PION PONTIAC (BOB) - MEMORIAL DR 21-20331 0900 Motor Vehicle Stop Citation/Warning Issued Location/Address: [CHI] GRANBY RD 21-20335 0909 Motor Vehicle Stop Citation/Warning Issued Location/Address: [CHI] GRANBY RD 21-20341 0924 Motor Vehicle Stop Citation/Warning Issued Location/Address: [CHI] GRANBY RD 21-20348 0937 Motor Vehicle Stop Citation/Warning Issued Location/Address: [CHI] GRANBY RD 21-20354 0953 Motor Vehicle Stop Citation/Warning Issued Location/Address: [CHI 1122] CHICOPEE LIQUORS - MEMORIAL DR 21-20363 1023 Motor Vehicle Stop Citation/Warning Issued Location/Address: [CHI] MONTGOMERY ST 21-20369 1031 Larceny Complaint -

Eden Housing Project Plan to Go Before the City Council Monday

Thursday, MAY 20, 2021 VOLUME LVIII, NUMBER 20 Your Local News Source Since 1963 SERVING DUBLIN, LIVERMORE, PLEASANTON, SUNOL Schools Set Eden Housing Project Reopening Plans for Plan to Go Before the Next Year City Council Monday By Dawnmarie Fehr By Aly Brown construction jobs for union REGIONAL — Local LIVERMORE — A project members and develop af- school districts have begun proposed for the Down- fordable units to meet state the work of planning for town Core will go before mandates. The project is the 2021-22 school year the council next week in supported by several Liver- and are expecting a re- a meeting that could span more and Bay Area anti- turn to a regular schedule. more than one day. (See EDEN, page 6) However, most are also of- Livermore Mayor Bob fering virtual options. Woerner said at a recent As guidelines from the council session that the At press time, The state continue to fluctuate, May 24 hearing for Eden Independent received a local districts prepare for a Housing — the 130-unit, letter from land-use attorney full open, but administra- Residents at Stoneridge Creek senior living community brought legendary actors back four-story affordable hous- Winston Stromberg, with to life for a two-day photo shoot. The photos will be features in a 2022 calendar. To tors caution that nothing is ing project proposed for the Latham & Watkins, who read more, see page 9. To view a photo gallery, visit independentnews.com/multimedia. certain at this point. city’s downtown core — represents the community (Photo – Doug Jorgensen) could take more than one “For next year, the group, Save Livermore guidelines from the state day due to the anticipated seem to be leaning toward number of public speakers. -

December 1999 of Trappe, Collegeville, Perkiomen Valley, Inc

The Chronicle A Publication of The Historical Society December 1999 of Trappe, Collegeville, Perkiomen Valley, Inc. Volume XXVIII, No. 5 Wa shington AnniversaryEx hibit The President's Message The 200th Anniversary of the death of President George Washington in Decem In teresting happenings are in progress at the Dewees Tavern ber 1799 will be observed at the Dewees and the Muhlenberg House. We have had a number of tour Museum, 301 W. Main Street, Trappe, groups visit us and a number are scheduled. We welcome them. beginningon Sunday, December 5th. The Our maintenance costs continue so we must ask our visitors exhibit will include prints of personages from the American Revolution who were and supporters fo r contributionsfrom time to time. involved with Washington and the We are gratefulfo r the Century Club support over the past Muhlenbergs. A unique reverse painting nine years, but some have neglected to keep up with their of Wakefield, the birthplace of Washing commitment. We plan to send letters of reminder. ton, on loan from the Rev. Robert Home, We would like to purchase two five-plated stoves fo r.the first will be shown. Anantique print ofWash floor cooking fireplaces. The cost is $7, 000 apiece. Ifanyo ne ington in his Masonic regalia will be a cares to donate one, or both, or a fraction of one, give me a call part of the exhibit. Muhlenberg House will not be open on December 5th. and we 'I/ negotiate. Furnishing the Muhlenberg House is One of the bicentennial (1932) framed important, but there is no rush to get it done. -

Virtual and Physical Environments in the Work of Pipilotti Rist, Doug Aitken, and Olafur Eliasson

Virtual and Physical Environments in the work of Pipilotti Rist, Doug Aitken, and Olafur Eliasson A thesis submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ART in the Art History Program of the College of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning April 2012 by Ashton Tucker B.A., Bowling Green State University College of Arts and Sciences Committee Chair: Morgan Thomas, Ph.D. Reader: Kimberly Paice, Ph.D. Reader: Jessica Flores, M.A. ABSTRACT The common concerns of artists Pipilotti Rist (b. 1962), Doug Aitken (b. 1968), and Olafur Eliasson (b. 1967) are symptomatic of key questions in contemporary art and culture. In this study, I examine key works by each artist, emphasizing their common interest in the interplay of virtual space and physical space and, more generally, their use of screen aesthetics. Their focus on the creative interplay of virtuality and physicality is indicative of their understanding of the fragility and uncertainty of physical perception in a world dominated by screen-based communication. In chapter one, I explore Pipilotti Rist’s Pour Your Body Out (7354 Cubic Meters) and argue that the artist creates work where screen based projection and installation are interrelated elements due to her interest in creating spaces that engage the viewer both physically and virtually. In chapter two, I discuss Doug Aitken’s work and argue that he democratizes the viewing experience in a more radical way than Pipilotti Rist. In the final chapter, I discuss the work of Olafur Eliasson as it relates to California Light and Space art and the phenomenological aspects of the eighteenth-century phantasmagoria.