Abraham Joshua Heschel, "No Time for Neutrality" Moral Grandeur and Spiritual Audacity, Pp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vincas Kudirka, Martynas Jankus, Jonas Šliūpas and the Making of Modern Lithuania Charles C

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University History Dissertations Department of History Summer 2013 Lithuanians in the Shadow of Three Eagles: Vincas Kudirka, Martynas Jankus, Jonas Šliūpas and the Making of Modern Lithuania Charles C. Perrin Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_diss Recommended Citation Perrin, Charles C., "Lithuanians in the Shadow of Three Eagles: Vincas Kudirka, Martynas Jankus, Jonas Šliūpas and the Making of Modern Lithuania." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2013. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_diss/35 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LITHUANIANS IN THE SHADOW OF THREE EAGLES: VINCAS KUDIRKA, MARTYNAS JANKUS, JONAS ŠLIŪPAS AND THE MAKING OF MODERN LITHUANIA by CHARLES PERRIN Under the Direction of Hugh Hudson ABSTRACT The Lithuanian national movement in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries was an international phenomenon involving Lithuanian communities in three countries: Russia, Germany and the United States. To capture the international dimension of the Lithuanian na- tional movement this study offers biographies of three activists in the movement, each of whom spent a significant amount of time living in one of -

International Press

International press The following international newspapers have published many articles – which have been set in wide spaces in their cultural sections – about the various editions of Europe Theatre Prize: LE MONDE FRANCE FINANCIAL TIMES GREAT BRITAIN THE TIMES GREAT BRITAIN LE FIGARO FRANCE THE GUARDIAN GREAT BRITAIN EL PAIS SPAIN FRANKFURTER ALLGEMEINE ZEITUNG GERMANY LE SOIR BELGIUM DIE ZEIT GERMANY DIE WELT GERMANY SUDDEUTSCHE ZEITUNG GERMANY EL MUNDO SPAIN CORRIERE DELLA SERA ITALY LA REPUBBLICA ITALY A NEMOS GREECE ARTACT MAGAZINE USA A MAGAZINE SLOVAKIA ARTEZ SPAIN A TRIBUNA BRASIL ARTS MAGAZINE GEORGIA A2 MAGAZINE CZECH REP. ARTS REVIEWS USA AAMULEHTI FINLAND ATEATRO ITALY ABNEWS.RU – AGENSTVO BUSINESS RUSSIA ASAHI SHIMBUN JAPAN NOVOSTEJ ASIAN PERFORM. ARTS REVIEW S. KOREA ABOUT THESSALONIKI GREECE ASSAIG DE TEATRE SPAIN ABOUT THEATRE GREECE ASSOCIATED PRESS USA ABSOLUTEFACTS.NL NETHERLANDS ATHINORAMA GREECE ACTION THEATRE FRANCE AUDITORIUM S. KOREA ACTUALIDAD LITERARIA SPAIN AUJOURD’HUI POEME FRANCE ADE TEATRO SPAIN AURA PONT CZECH REP. ADESMEUFTOS GREECE AVANTI ITALY ADEVARUL ROMANIA AVATON GREECE ADN KRONOS ITALY AVLAIA GREECE AFFARI ITALY AVLEA GREECE AFISHA RUSSIA AVRIANI GREECE AGENZIA ANSA ITALY AVVENIMENTI ITALY AGENZIA EFE SPAIN AVVENIRE ITALY AGENZIA NUOVA CINA CHINA AZIONE SWITZERLAND AGF ITALY BABILONIA ITALY AGGELIOF OROS GREECE BALLET-TANZ GERMANY AGGELIOFOROSTIS KIRIAKIS GREECE BALLETTO OGGI ITALY AGON FRANCE BALSAS LITHUANIA AGORAVOX FRANCE BALSAS.LT LITHUANIA ALGERIE ALGERIA BECHUK MACEDONIA ALMANACH SCENY POLAND -

Patient–Physician Collaboration in Rheumatology: a Necessity

Miscellaneous RMD Open: first published as 10.1136/rmdopen-2017-000499 on 18 July 2017. Downloaded from VIEWPOINT Patient–physician collaboration in rheumatology: a necessity Elena Nikiphorou,1,2 Alessia Alunno,3 Loreto Carmona,4 Marios Kouloumas,5 Johannes Bijlsma,6 Maurizio Cutolo7 To cite: Nikiphorou E, ABSTRACT has set important milestones and allowed the Alunno A, Carmona L, Over the past few decades, there has been significant specialty to progress to a different level. et al. Patient–physician and impressive progress in the understanding and collaboration in rheumatology: management of rheumatic diseases. One of the key a necessity. RMD Open reasons for succeeding in making this progress has PATIENTS AND PHYSICIANS WORKING IN 2017;3:e000499. doi:10.1136/ rmdopen-2017-000499 been the increasingly stronger partnership between PARTNERSHIP physicians and patients, setting a milestone in patient The relationship between patients and care. In this viewpoint, we discuss the recent evolution physicians has received attention since the ► Prepublication history for of the physician–patient relationship over time in Europe, Hippocratic times.1 It is undoubtedly a rela- this paper is available online. reflecting on the ‘journey’ from behind the clinic walls To view these files please visit tionship that has changed and matured through to clinical and research collaborations at national the journal online (http:// dx. doi. and international level and the birth of healthcare through the years, with almost a complete org/ 10. 1136/ rmdopen- 2017- turnaround of role and attitude: the emphasis 000499). professional and ‘rheumatic’ patient organisations. The role of expert patients and patient advocates in clinical is now on the patient talking and the physi- Received 16 May 2017 and scientific committees now represents a core part cian listening and understanding the needs of Revised 13 June 2017 of the decision-making process. -

Tribute Planned for Beheaded Teacher

MONDAY, OCTOBER 19, 2020 06 Israel, UAE News in brief u A landslide early on to sign deal Sunday killed at least 14 for 28 weekly Tribute planned for military personnel and left eight missing in central flights Vietnam, the government said, in what could be the country’s largest military loss beheaded teacher in peace time as it battles major flooding. The mudslide hit the barracks of a unit of Vietnam’s 4th Military Landslide 11th person was Region in the central province of Quang Tri, the hits barracks • government said in a statement on its website. detained yesterday It occurred days after another landslide killed 13 in Vietnam, Reuters | Jerusalem people, mostly soldiers, in the neighbouring province killing 14 The 47-year-old of Thua Thien Hue. srael and the United Arab teacher• was killed Nagorno- u The defence IEmirates will a sign a deal on Friday outside ministry of the yesterday to allow 28 weekly Karabakh says his school Nagorno-Karabakh commercial flights between death toll among region said on Sunday Israel’s Ben Gurion airport, its military rises it had recorded another Dubai and Abu Dhabi, Isra- • The assailant, who to 673 40 casualties among its el’s Transportation Ministry was born in Russia of military, pushing the military death toll to 673 since said on Sunday. Chechen origin, was fighting with Azeri forces erupted on Sept. 27. The fighting has surged to its worst The agreement, which level since the 1990s, when some 30,000 people were killed. also allows unlimited char- shot dead by police ter flights to a smaller air- soon after the attack u Thousands of Thai anti-government protesters took over People gather in front of the Bois d’Aulne college after the attack in the Paris key intersections in Bangkok yesterday, defying a ban on protests port in southern Israel and suburb of Conflans St Honorine, France 10 weekly cargo flights, for the fourth day with chants of “down with dictatorship” and “reform the Reuters | Paris monarchy.” Demonstrations have persisted comes after Israel and UAE Prophet is blasphemous. -

11-07 Chayei Sarah

Beshallach / 13 Shevat 5776 “Miriam the prophetess”! by Anselm Feuerbach ! ! ִתּ ַקּח ִמרְ יָם ַה ִנְּביאָה אֲחוֹת אַהֲרֹן, ֶאת ַהתֹּף בְּיָ ָדהּ; וַ ֵתּ ֶצאן ָ ָכל- ַהנָּ ִשׁים ֶאַחֲר ָיה, ֻבְּת ִפּים ִוּבמְ חֹלת. וַ ַתּ ַען ָל ֶהם, ִמרְ יָם: ... ִשׁירוּ ַליהוָה ִכּי- ָגאֹה ָגּאָה ! Exodus 15:20-2 Miriam the prophetess, the sister of Aaron, took a tambourine in her hand; and all the women went out after her with tambourines and with dances. And Miriam sang to them: !“Sing to Adonai, for G-d is highly exalted…” ! In the Bible, Miriam, sister of Moses and Aaron takes a secondary role to her brothers. Were anyone to ask, “who led the Israelite people out of Egypt?,” most certainly the answer would be “Moses” or maybe “Moses and his brother Aaron.” But, seldom would the question elicit the answer, “Miriam.” Yet, this week’s Torah portion tells us that “Miriam the prophetess… took the tambourine in her hand; and all the women followed her with tambourines and dances. And !Miriam sang to them….” Biblical commentators (including Fox, Plaut, Alter) tell us that it was customary in ancient days for women to lead the community in a victory dance and song following the defeat of an enemy. This was perhaps the scenario as the crossing of the Sea of Reeds marked a successful exodus from 400 years of slavery in Egypt. It’s very clear that Miriam sang to “them” as in all the men, not just the women who followed her with tambourine in hand for a victory dance. -

JOM KIPUR DAN POMIRENJA U Ovom Broju Vijesti Iz Op{Tine

GLASILO JEVREJSKE ZAJEDNICE BOSNE I HERCEGOVINE broj 59. Sarajevo, septembar 2013. / ti{ri / he{van 5774. JOM KIPUR DAN POMIRENJA U ovom broju Vijesti iz Op{tine Izlazi ~etiri vrlo ozbiljan plan rada sekcije. Najveća pažnja je odmah bila puta godi{nje GODI[NJA SKUP[TINA GODIŠNJA SKUPŠTINA fokusirana na pokušaj da se naša omladina zainteresuje prije Published four svega za svoje jevrejsko porijeklo, te sudjelovanje u vjerskom times a year JEVREJSKE OP[TINE 3.str životu u okviru J.O. Članovi sekcije su bili angažovani oko Broj 59. JEVREJSKE OPŠTINE priprema velikih, najznačajnijih, ali i ostalih praznika u septembar, 2013. Boris Ko`emjakin Opštini. Naravno,bili su aktivni i u svojim individualnim Predhodne godine, u maju 2012. godine, na izbornoj djelatnostima u drugim poslovima vezani za djelatnost komisije Glasnik Jevrejske Skupštini izabrali smo novo Predsjedništvo, na mandat (odlazak u druge gradove zbog organizovanja vjerskog života, zajednice Bosne i od četri godine.Na godišnjoj Skupštini, nakon praktično te sahrane itd.).Ne treba posebno napominjati da su redovno Hercegovine HASIDSKE SLIKOVITE šesnaest mjeseci rada, u sptem,bru 2013. Godine, sumirali smo održavane molitve petkom navečer (Arvid shel Shabat). Herald of Jewish rezultate rada za prethodni period, osvrćući se kritički na rad, Community of Bosnia and a sve sa željom da naš zajednički život i rad bude sadržajniji i Što se tiče predavanja, komisija ih je shvatila kao pilot Herzegovina PRI^E MELITE KRAUS 4.str bogatiji, da ga osvježimo novim idejama i sugestijama članstva projekte i kao uvod u daljnje aktivnosti u tom smislu, pošto Izdava~/Publisher Pavle Kaunitz Opštine, da se kritički osvrnemo i sagledamo rad aktuelnog bi nakon uvodna četri predavanja, koje su održali svi članovi Jevrejska zajednica Predsjedništva Opštine, tze stručnih službi,komisija i sekcija komisije, slijedila predavanja koja bi uz pomoć članova Bosne i Hercegovine koje djeluju u okviru Jevrejske Opštine. -

Why How What

1.855.55MOTEK (66835) WWW.MOTEK.CA Motek Cultural Initiative (MOTEK) is an innovative non-profit charitable organization, established to showcase contemporary Israeli music to diverse audiences. MOTEK began with a vision and a dream for change! By showcasing and introducing talented Israeli musicians to the mainstream, we are fostering a new generation’s appreciation for Israel across multicultural communities. MOTEK improves perceptions of Israel using music as a tool to transcend barriers, promote positive attitudes and unity. WHY HOW WHAT To reveal a POSITIVE IMAGE of Israel Through the Produce Concerts, Advocacy Events, while strengthening our next generation’s power of music! and unique programs to improve connection to Israel. Israel’s online reputation. 1.855.55MOTEK (66835) WWW.MOTEK.CA CASE FOR SUPPORT 2015 MOTEK 4th Annual Gala Who We Are What We Do Become a Supporter Sponsorship Programs About Us Produce Donor Wall Marketing & Media Machine Board & Members Develop MOTEK’s Fan Club Fan demographics Implement Brand exposure MOTEK’s Future Sponsorship Package 1.855.55MOTEK (66835) WWW.MOTEK.CA MOTEK 4 th ANNUAL GALA PRESENTS The Soul of Israeli Sound accompanied by a 12 piece ensemble It is with great pride and excitement that Motek Cultural Initiative 4th Annual Gala presents the Soul of Israeli Sound; Shlomi Shabat accompanied by a 12- piece ensemble on Thursday May 7, 2015 at the Queen Elizabeth Theatre. This date also marks Lag Ba’Omer, a festive day of celebration in the Jewish calendar. Shlomi Shabat is an Israeli singer and composer, known as the SOUL of Israeli music. Shlomi’s rise to fame began in the 1980’s, when he pioneered a new fusion of Mediterranean rock, blues, and Spanish music. -

Jury Members List (Preliminary) VERSION 1 - Last Update: 1 May 2015 12:00CEST

Jury members list (preliminary) VERSION 1 - Last update: 1 May 2015 12:00CEST Country Allocation First name Middle name Last name Commonly known as Gender Age Occupation/profession Short biography (un-edited, as delivered by the participating broadcasters) Albania Backup Jury Member Altin Goci male 41 Art Manager / Musician Graduated from Academy of Fine Arts for canto. Co founder of the well known Albanian band Ritfolk. Excellent singer of live music. Plays violin, harmonica and guitar. Albania Jury Member 1 / Chairperson Bojken Lako male 39 TV and theater director Started music career in 1993 with the band Fish hook, producer of first album in 1993 King of beers. In 1999 and 2014 runner up at FiK. Many concerts in Albania and abroad. Collaborated with Band Adriatica, now part of Bojken Lako band. Albania Jury Member 2 Klodian Qafoku male 35 Composer Participant in various concerts and contests, winner of several prizes, also in children festivals. Winner of FiK in 2005, participant in ESC 2006. Composer of first Albanian etno musical Life ritual. Worked as etno musicologist at Albanology Study Center. Albania Jury Member 3 Albania Jury Member 4 Arta Marku female 45 Journalist TV moderator of art and cultural shows. Editor in chief, main editor and editor of several important magazines and newspapers in Albania. Albania Jury Member 5 Zhani Ciko male 69 Violinist Former Artistic Director and Director General of Theater of Opera and Ballet of Tirana. Former Director of Artistic Lyceum Jordan Misja. Artistic Director of Symphonic Orchestra of Albanian Radio Television. One of the most well known Albanian musicians. -

COMPLETE DRAFT Copy Copy

Peace and Security beyond Military Power: The League of Nations and the Polish-Lithuanian Dispute (1920-1923) Chiara Tessaris Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2014 © 2014 Chiara Tessaris All rights reserved ABSTRACT Peace and Security beyond Military Power: The League of Nations and the Polish- Lithuanian Dispute Chiara Tessaris Based on the case study of the mediation of the Polish-Lithuanian dispute from 1920 to 1923, this dissertation explores the League of Nations’ emergence as an agency of modern territorial and ethnic conflict resolution. It argues that in many respects, this organization departed from prewar traditional diplomacy to establish a new, broader concept of security. At first the league tried simply to contain the Polish-Lithuanian conflict by appointing a Military Commission to assist these nations in fixing a final border. But the occupation of Vilna by Polish troops in October 1920 exacerbated Polish-Lithuanian relations, turning the initial border dispute into an ideological conflict over the ethnically mixed region of Vilna, claimed by the Poles on ethnic grounds while the Lithuanians considered it the historical capital of the modern Lithuanian state. The occupation spurred the league to greater involvement via administration of a plebiscite to decide the fate of the disputed territories. When this strategy failed, Geneva resorted to negotiating the so-called Hymans Plan, which aimed to create a Lithuanian federal state and establish political and economic cooperation between Poland and Lithuania. This analysis of the league’s mediation of this dispute walks the reader through the league’s organization of the first international peacekeeping operation, its handling of the challenges of open diplomacy, and its efforts to fulfill its ambitious mandate not just to prevent war but also to uproot its socioeconomic and ethnic causes. -

Growing Together

Programming and Education Guide 5780 / 2019-2020 Growing Together “As a Tree Rooted by Tranquil Waters“ -Psalms 1:3 Shabbat Afternoon Parsha Week at a glance... How many ways are there of looking at a story? Tradition tells us that there are seventy faces to the Torah. Join in as this class delves into many of the perspectives for understanding the SUNDAY MONDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY world’s all-time bestseller. Following the schedule of the weekly Torah portion, Rabbi Michael Monthly Weekly Weekly Winter Davies will guide the class through discussion of text and some of the classic commentaries in Breakfast Ketuvim Lunchtime Tisch order to gain insight into the fascinating stories, familiar and overlooked passages and cryptic Minyan with Kenny Talmud Page 3 instructions that make up the Bible. Enrich your Shabbat conversation and carry the messages Page 15 Page 7 Page 7 with you wherever you go! Class is appropriate both for beginners as well as those with Torah Weekly Torah Weekly Cholent study background. Study & Learn Dates & Times: Shabbat Afternoons in the Fall, Spring, and Summer. 45 minutes before Page 6 Page 7 afternoon services (check weekly schedule for exact times). Please check synagogue SHABBAT announcements or website for more information. Weekly Shabbat Weekly Weekly Summer Afternoon Seudah Youth Tisch Seudah Shlishit Parsha Shlishit Groups Page 3 It’s not just a meal, it’s Seudah Shlishit! Join the ever-growing group that attends the brief Page 3 Page 3 Page 4 Shabbat afternoon service and continues on to share the Seudah Shlishit meal with song and Monthly Weekly TOT Monthly TOTally Monthly Shabbat study. -

Songs of Grief, Joy, and Tragedy Among Iraqi Jews

EXILED NOSTALGIA AND MUSICAL REMEMBRANCE: SONGS OF GRIEF, JOY, AND TRAGEDY AMONG IRAQI JEWS BY LILIANA CARRIZO DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Musicology in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2018 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Donna A. Buchanan, Chair Professor Gabriel Solis Associate Professor Christina Bashford Professor Kenneth M. Cuno ABSTRACT This dissertation examines a practice of private song-making, one whose existence is often denied, among a small number of amateur Iraqi Jewish singers in Israel. These individuals are among those who abruptly emigrated from Iraq to Israel in the mid twentieth century, and share formative experiences of cultural displacement and trauma. Their songs are in a mixture of colloquial Iraqi dialects of Arabic, set to Arab melodic modes, and employ poetic and musical strategies of obfuscation. I examine how, within intimate, domestic spheres, Iraqi Jews continually negotiate their personal experiences of trauma, grief, joy, and cultural exile through musical and culinary practices associated with their pasts. Engaging with recent advances in trauma theory, I investigate how these individuals utilize poetic and musical strategies to harness the unstable affect associated with trauma, allowing for its bodily embrace. I argue that, through their similar synaesthetic capability, musical and culinary practices converge to allow for powerful, multi-sensorial evocations of past experiences, places, and emotions that are crucial to singers’ self-conceptions in the present day. Though these private songs are rarely practiced by younger generations of Iraqi Jews, they remain an under-the-radar means through which first- and second-generation Iraqi immigrants participate in affective processes of remembering, self-making, and survival. -

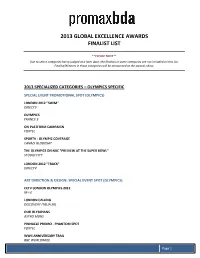

2013 Global Excellence Awards Finalist List

2013 GLOBAL EXCELLENCE AWARDS FINALIST LIST **PLEASE NOTE** Due to select categories being judged at a later date, the finalists in some categories are not included on this list. Finalist/Winners in those categories will be announced at the awards show. 2013 SPECIALIZED CATEGORIES – OLYMPICS SPECIFIC SPECIAL EVENT PROMOTIONAL SPOT (OLYMPICS) LONDON 2012 "SWIM" DIRECTV OLYMPICS FRANCE 3 ON PLATFORM CAMPAIGN FOXTEL SPORTV - OLYMPIC COVERAGE CANAIS GLOBOSAT THE OLYMPICS ON NBC "PREVIEW AT THE SUPER BOWL" STUDIO CITY LONDON 2012 "TRACK" DIRECTV ART DIRECTION & DESIGN: SPECIAL EVENT SPOT (OLYMPICS) CCTV LONDON OLYMPICS 2012 M-I-E LONDON CALLING DISCOVERY ITALIA SRL OUR OLYMPIANS ASTRO MBNS PINNACLE PROMO - PHANTOM SPOT FOXTEL WWII ANNIVERSARY TRAIL BBC WORLDWIDE Page 1 CINEMATIC SPECIFIC PROMOS AT THE MOVIES AXN IT’S A MAN’S WORLD AXN ITALY DECEPTION THEATER :90 NBC ENTERTAINMENT MARKETING & DIGITAL MANKIND FOX CHANNELS ITALY M-NET MOVIES ODYSSEY 60 LAUNCH CLEARWATER FOR M-NET MOVIES PUMP UP SPRING ON DSTV STUDIO ZOO FOR DSTV THE WALKING DEAD CINEMA ACTIVATION IRELAND/DAVENPORT TELEVISION - VIDEO PRESENTATION: CHANNEL PROMOTION GENERAL CHANNEL IMAGE SPOT CANAL+ SCREENS 2.0 BOND STREET FILM STOCKHOLM COMEDY CENTRAL LAUNCH "FUNNY BONE" VIACOM18 MEDIA PVT. LTD. (COMEDY CENTRAL INDIA) IMAGE PROMO "SUPERLOGO" CREATIVE SOLUTIONS - P7S1 TV DEUTSCHLAND GMBH SUPERSPORT POV ORIJIN CMORE IMAGE SPOT BOND STREET FILM STOCKHOLM SUPERSPORT TRANSFORMERS ORIJIN GENERAL CHANNEL IMAGE CAMPAIGN COMEDY CENTRAL LAUNCH "FUNNY BONE" VIACOM18 MEDIA PVT. LTD. (COMEDY