Scabies Handbook

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Expanding the Role of Dermatology at the World Health Organization and Beyond

EDITORIAL A Seat at the Big Table: Expanding the Role of Dermatology at the World Health Organization and Beyond y patient can’t breathe. From across Kaposi’s sarcoma, seborrheic dermatitis, her- the busy, open ward, you can see the pes zoster, scabies, papular pruritic eruption, Mplaques of Kaposi’s sarcoma riddling eosinophilic folliculitis, tinea, molluscum, drug her skin. The impressive woody edema has reactions, and oral candidiasis (World Health enlarged her legs to the size of small tree trunks. Organization, in press). These conditions have We don’t have access to confirmatory pulmo- a high prevalence in developing countries, but nary testing in Kenya, but she probably wouldn’t many lack internationally agreed-on standards survive a bronchoscopy anyway. of care. This deficit led to inconsistent and some- When she dies six hours later, we can be pret- times dangerous treatment approaches or lack of ty sure that it is her pulmonary Kaposi’s sarcoma, essential drugs. Critically, dermatologists were along with her underlying HIV, that killed her. involved at all levels of the guideline-develop- Her family tells us that she had dark spots on ment process, including Cochrane reviews of the her skin and swelling in her legs for more than literature, guideline development and review, a year before she presented to the hospital. Like and additional funding for the project from many of our patients in East Africa, she sought the International Foundation for Dermatology help from a traditional healer for many months (http://www.ifd.org). before turning to the biomedical health system, Although diseases such as Kaposi’s sarcoma only hours before her death. -

Cutaneous Manifestations of HIV Infection Carrie L

Chapter Title Cutaneous Manifestations of HIV Infection Carrie L. Kovarik, MD Addy Kekitiinwa, MB, ChB Heidi Schwarzwald, MD, MPH Objectives Table 1. Cutaneous manifestations of HIV 1. Review the most common cutaneous Cause Manifestations manifestations of human immunodeficiency Neoplasia Kaposi sarcoma virus (HIV) infection. Lymphoma 2. Describe the methods of diagnosis and treatment Squamous cell carcinoma for each cutaneous disease. Infectious Herpes zoster Herpes simplex virus infections Superficial fungal infections Key Points Angular cheilitis 1. Cutaneous lesions are often the first Chancroid manifestation of HIV noted by patients and Cryptococcus Histoplasmosis health professionals. Human papillomavirus (verruca vulgaris, 2. Cutaneous lesions occur frequently in both adults verruca plana, condyloma) and children infected with HIV. Impetigo 3. Diagnosis of several mucocutaneous diseases Lymphogranuloma venereum in the setting of HIV will allow appropriate Molluscum contagiosum treatment and prevention of complications. Syphilis Furunculosis 4. Prompt diagnosis and treatment of cutaneous Folliculitis manifestations can prevent complications and Pyomyositis improve quality of life for HIV-infected persons. Other Pruritic papular eruption Seborrheic dermatitis Overview Drug eruption Vasculitis Many people with human immunodeficiency virus Psoriasis (HIV) infection develop cutaneous lesions. The risk of Hyperpigmentation developing cutaneous manifestations increases with Photodermatitis disease progression. As immunosuppression increases, Atopic Dermatitis patients may develop multiple skin diseases at once, Hair changes atypical-appearing skin lesions, or diseases that are refractory to standard treatment. Skin conditions that have been associated with HIV infection are listed in Clinical staging is useful in the initial assessment of a Table 1. patient, at the time the patient enters into long-term HIV care, and for monitoring a patient’s disease progression. -

Arthropod Parasites in Domestic Animals

ARTHROPOD PARASITES IN DOMESTIC ANIMALS Abbreviations KINGDOM PHYLUM CLASS ORDER CODE Metazoa Arthropoda Insecta Siphonaptera INS:Sip Mallophaga INS:Mal Anoplura INS:Ano Diptera INS:Dip Arachnida Ixodida ARA:Ixo Mesostigmata ARA:Mes Prostigmata ARA:Pro Astigmata ARA:Ast Crustacea Pentastomata CRU:Pen References Ashford, R.W. & Crewe, W. 2003. The parasites of Homo sapiens: an annotated checklist of the protozoa, helminths and arthropods for which we are home. Taylor & Francis. Taylor, M.A., Coop, R.L. & Wall, R.L. 2007. Veterinary Parasitology. 3rd edition, Blackwell Pub. HOST-PARASITE CHECKLIST Class: MAMMALIA [mammals] Subclass: EUTHERIA [placental mammals] Order: PRIMATES [prosimians and simians] Suborder: SIMIAE [monkeys, apes, man] Family: HOMINIDAE [man] Homo sapiens Linnaeus, 1758 [man] ARA:Ast Sarcoptes bovis, ectoparasite (‘milker’s itch’)(mange mite) ARA:Ast Sarcoptes equi, ectoparasite (‘cavalryman’s itch’)(mange mite) ARA:Ast Sarcoptes scabiei, skin (mange mite) ARA:Ixo Ixodes cornuatus, ectoparasite (scrub tick) ARA:Ixo Ixodes holocyclus, ectoparasite (scrub tick, paralysis tick) ARA:Ixo Ornithodoros gurneyi, ectoparasite (kangaroo tick) ARA:Pro Cheyletiella blakei, ectoparasite (mite) ARA:Pro Cheyletiella parasitivorax, ectoparasite (rabbit fur mite) ARA:Pro Demodex brevis, sebacceous glands (mange mite) ARA:Pro Demodex folliculorum, hair follicles (mange mite) ARA:Pro Trombicula sarcina, ectoparasite (black soil itch mite) INS:Ano Pediculus capitis, ectoparasite (head louse) INS:Ano Pediculus humanus, ectoparasite (body -

WHO GUIDELINES for the Treatment of Treponema Pallidum (Syphilis)

WHO GUIDELINES FOR THE Treatment of Treponema pallidum (syphilis) WHO GUIDELINES FOR THE Treatment of Treponema pallidum (syphilis) WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data WHO guidelines for the treatment of Treponema pallidum (syphilis). Contents: Web annex D: Evidence profiles and evidence-to-decision frameworks - Web annex E: Systematic reviews for syphilis guidelines - Web annex F: Summary of conflicts of interest 1.Syphilis – drug therapy. 2.Treponema pallidum. 3.Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 4.Guideline. I.World Health Organization. ISBN 978 92 4 154980 6 (NLM classification: WC 170) © World Health Organization 2016 All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization are available on the WHO website (http://www.who.int) or can be purchased from WHO Press, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel.: +41 22 791 3264; fax: +41 22 791 4857; email: [email protected]). Requests for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications – whether for sale or for non-commercial distribution– should be addressed to WHO Press through the WHO website (http://www.who.int/about/licensing/ copyright_form/index.html). The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted and dashed lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. -

Wildlife Parasitology in Australia: Past, Present and Future

CSIRO PUBLISHING Australian Journal of Zoology, 2018, 66, 286–305 Review https://doi.org/10.1071/ZO19017 Wildlife parasitology in Australia: past, present and future David M. Spratt A,C and Ian Beveridge B AAustralian National Wildlife Collection, National Research Collections Australia, CSIRO, GPO Box 1700, Canberra, ACT 2601, Australia. BVeterinary Clinical Centre, Faculty of Veterinary and Agricultural Sciences, University of Melbourne, Werribee, Vic. 3030, Australia. CCorresponding author. Email: [email protected] Abstract. Wildlife parasitology is a highly diverse area of research encompassing many fields including taxonomy, ecology, pathology and epidemiology, and with participants from extremely disparate scientific fields. In addition, the organisms studied are highly dissimilar, ranging from platyhelminths, nematodes and acanthocephalans to insects, arachnids, crustaceans and protists. This review of the parasites of wildlife in Australia highlights the advances made to date, focussing on the work, interests and major findings of researchers over the years and identifies current significant gaps that exist in our understanding. The review is divided into three sections covering protist, helminth and arthropod parasites. The challenge to document the diversity of parasites in Australia continues at a traditional level but the advent of molecular methods has heightened the significance of this issue. Modern methods are providing an avenue for major advances in documenting and restructuring the phylogeny of protistan parasites in particular, while facilitating the recognition of species complexes in helminth taxa previously defined by traditional morphological methods. The life cycles, ecology and general biology of most parasites of wildlife in Australia are extremely poorly understood. While the phylogenetic origins of the Australian vertebrate fauna are complex, so too are the likely origins of their parasites, which do not necessarily mirror those of their hosts. -

STD Glossary of Terms

STD 101 In A Box- STD Glossary of Terms Abstinence Not having sexual intercourse Acquired A disease of the human immune system caused by the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV). HIV/AIDS represents the entire range of Immunodeficiency disease caused by the HIV virus from early infection to late stage Syndrome (AIDS) symptoms. Anal Intercourse Sexual contact in which the penis enters the anus. Antibiotic A medication that either kills or inhibits the growth of a bacteria. Antiviral A medication that either kills or inhibits the growth of a virus. A thinning of tissue modified by the location. In epidermal atrophy, the epidermis becomes transparent with a loss of skin texture and cigarette Atrophic paper-like wrinkling. In dermal atrophy, there is a loss of connective tissue and the lesion is depressed. A polymicrobial clinical syndrome resulting from replacement of the Bacterial Vaginosis normal hydrogen peroxide producing Lactobacillus sp. in the vagina with (BV) high concentrations of anaerobic bacteria. The common symptom of BV is abnormal homogeneous, off-white, fishy smelling vaginal discharge. Cervical Motion A sign found on pelvic examination suggestive of pelvic pathology; when Tenderness (CMT) movement of the cervix during the bimanual exam elicits pain. The lower, cylindrical end of the uterus that forms a narrow canal Cervix connecting the upper (uterus) and lower (vagina) parts of a woman's reproductive tract. The most common sexually transmitted bacterial infection in the U.S., caused by the bacteria Chlamydia trachomatis. Often no symptoms are present, especially in women. Untreated chlamydia can cause sterility, Chlamydia Pelvic Inflammatory Disease (PID), and increase the chances for life- threatening tubal pregnancies. -

Pedianews Volume VI, Issue II the Official Newsletter of the Student Society of Pediatric Advocates (Rxpups) May 2018

1 PediaNews Volume VI, Issue II The Official Newsletter of the Student Society of Pediatric Advocates (RxPups) May 2018 Inside this issue LICEnse to Kill LICEnse to Kill ................... 1-2 Written by: Kirty Patel, Pharm.D. Candidate 2020 Pediatric Idiopathic Thrombocytopenia Purpura ................................. 3-5 It is a dreadful feeling of anxiety when any parent, teacher, or Obesity in Children .......... 6-8 other caregiver discovers lice in a child’s hair. They begin to look back on the past few days and realize that the child has been scratching their Editors head frequently, which is a common sign of head lice. The itching is caused by an allergic reaction to louse saliva. The caregiver may wonder Linda Logan, Pharm.D., BCPS, BCACP why they didn’t previously notice the symptoms but know they can Faculty Advisor contact their local pharmacist with questions, concerns, and guidance Alicia Sanchez, Pharm.D., for the treatment process. PGY2 Pediatric Pharmacy Upon obtaining the phone call, the pharmacist wants to confirm Resident that the child does in fact have lice. The pharmacist explains to the Namita Patel, PharmD caregiver that although lice are small, they can be detected by the Candidate Class of 2019 University of Georgia naked eye. The best way to detect a child’s current state of infestation College of Pharmacy is to examine their scalp for nits (lice eggs) using a magnifying lens and a toothpick comb. Empty nits are lighter in color and further from the scalp, but do not necessarily indicate an active infiltration of lice.1 It is also important to be aware that nits can be misidentified as dandruff, hair spray residue, or even dirt particles that have lodged into the patient’s scalp. -

Scabies, Incomplete Lupus Erythematosus and Henoch-Schonlein Purpura: a Case Report

Scabies, Incomplete Lupus Erythematosus and Henoch-Schonlein Purpura: A Case Report Yang Fang Wu First Aliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University Jing Jing Wang Jinling Hospital Hui Hui Liu First Aliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University Wei Xia Chen First Aliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University Peng Hu ( [email protected] ) First Aliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2144-9806 Case report Keywords: Antinuclear antibody, Henoch-Schonlein purpura, immunoglobulin A, proteinuria, scabies Posted Date: September 18th, 2020 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-63971/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Page 1/8 Abstract BackgroundHenoch-Schonlein purpura (HSP) is a common autoimmune vasculitis in childhood. Although the detailed etiology of HSP remains unknown, several triggers, especially for infectious agents, have been proved to be associated with HSP onset. Case presentation: In the present report, we describe an unusual patient who suffered from HSP and incomplete lupus erythematosus (ILE) on day 8 after scabies, mainly based on nonthrombocytopenic purpura, abdominal pain, medium proteinuria, positive antinuclear antibody (ANA) and skin scrapings. A course of pulse methylprednisolone (10mg/kg/day) was administered for 6 days, followed by oral prednisone (1mg/kg/day). On day 18, the purpuric rashes almost disappeared, whereas medium proteinuria still existed. In this circumstance, a renal biopsy was performed with the informed consent of the parents. According to the criteria proposed by the International Study of Kidney Disease in Children, this patient was classied as class IIIb. The immunouorescence microscopy revealed granular deposits of IgA, IgM and C3 in the glomerular mesangium. -

PATIENT INFORMATION LEAFLET Genital Warts

PATIENT INFORMATION LEAFLET E A D V Genital warts (Condylomata acuminata) task force “skin disease in pregnancy” The aim of this leaflet This leaflet has been written to help you understand more about genital warts. It will tell you what it is, what causes it, what can be done about it, and where you can find out more information about it. What are genital warts? Genital or more accurately anogenital warts are skin lesions of the genital, perineal and anal areas; the medical term is condylomata acuminata. What causes genital warts? Genital warts are an infectious disease caused by sexually transmitted viruses, the Human Papilloma Virus (HPV), types 6 and 11. The incubation period (time between infectious contact and showing clinical signs) can be as long as eight months. Most infections by HPV cause no symptoms and clear within 2 years. This means that you might not realize that you carry the virus, (and there is a chance that you may infect another person without knowing it). The virus can persist for months or years in the skin, with or without symptoms. If the warts reappear after clearing it is usually due to the original not a new infection. Infection can occur in up to 30% of women between 20 and 30 years of age; elderly women are less frequently affected. Are genital warts hereditary? No. What are the signs and symptoms of genital warts? The presence of external genital warts (at the outside of the ano-genital skin) is nearly always detected by the woman herself. You do not usually feel them but there may be some degree of itching. -

Epidemiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Scabies in a Dermatology Office

J Am Board Fam Med: first published as 10.3122/jabfm.2017.01.160190 on 6 January 2017. Downloaded from ORIGINAL RESEARCH Epidemiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Scabies in a Dermatology Office Kathryn L. Anderson, MD, and Lindsay C. Strowd, MD Background: Scabies is a neglected skin disease, and little is known about current incidence and treat- ment patterns in the United States. The purpose of this study was to examine demographic data, treat- ment types, success of treatment, and misdiagnosis rate of scabies in an outpatient dermatology clinic. Methods: A retrospective chart review of patients diagnosed with scabies within the past 5 years was performed. Results: A total of 459 charts were identified, with 428 meeting inclusion criteria. Demographic data, diagnostic method, treatment choice, misdiagnosis rate, treatment failure, and itching after scabies are also reported. Children were the largest age group diagnosed with scabies, at 38%. Males (54%) were diagnosed with scabies more than females. The majority of diagnoses were made by visualizing ova, feces, or mites on light microscopy (58%). At the time of diagnosis, 45% of patients had been misdiag- nosed by another provider. Topical permethrin was the most common treatment used (69%), followed by a combination of topical permethrin and oral ivermectin (23%), oral ivermectin (7%), and other treatments (1%). Conclusion: Our findings suggest that more accurate and faster diagnostic methods are needed to limit unnecessary treatment and expedite appropriate therapy for scabies. (J Am -

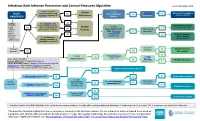

Infectious Rash Infection Prevention and Control Measures Algorithm Issued: November 2019

Infectious Rash Infection Prevention and Control Measures Algorithm Issued: November 2019 Is rash crusted, Contact Is rash RASH scaly or papular and Yes maculopapular? Is Measles Yes Airborne Precautions scabies is suspected? Precautions Yes suspected? Contact site ICP OBSERVED Apular? STAFF: Has scabies been No Perform Droplet Precautions reconsidered & ruled Routine Is rash hand No out if diagnosed as Yes Contact site ICP hygiene psoriasis or eczema? Yes Practices petechial/purpuric Is person >5 Put on AND Neisseria Yes years old? meningitidis gloves Yes No Droplet/Contact for direct suspected? Precautions Is medication/ contact Contact site ICP with lesions allergic reaction or heat rash suspected? Is person Is fever an adult? No Droplet/Contact present? Yes Yes Precautions Is Scarlet Fever Yes Is rash Yes Is Fifth erythematous? suspected? Cover rash if possible. No Disease Routine Practices Person with rash: Perform hand hygiene. suspected? Yes P ut on procedure mask if Measles, Neisseria meningitidis, Chickenpox or disseminated Shingles suspected. If unable to tolerate mask, consider room placement. Airborne/Contact Precautions Yes Is Chickenpox suspected? Yes Yes No Contact Precautions Is rash Is person immune Can rash be Is rash disseminated No (on 3 or more No compromised? covered? vesicular? Is Shingles suspected? Yes Yes dermatomes)? Routine Practices No Is Hand foot and mouth Pediatric AND disease suspected? Yes incontinent? Yes Contact Precautions Algorithm includes initial IP&C highlights only, not treatment recommendations. Consider differential and additional diagnoses; if suspected cause/the answer “No” is not shown, use best clinical judgment. This algorithm includes highlights of some common or consequential infectious rashes. -

Sexually Transmitted Infections–Summary of CDC Treatment

Sexually Transmitted Infections Summary of CDC Treatment Guidelines—2021 Bacterial Vaginosis • Cervicitis • Chlamydial Infections • Epididymitis Genital Herpes Simplex • Genital Warts (Human Papillomavirus) • Gonococcal Infections Lymphogranuloma Venereum • Nongonococcal Urethritis (NGU) • Pediculosis Pubis Pelvic Inflammatory Disease• Scabies • Syphilis • Trichomoniasis U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention National Network of STD Clinical Prevention Training Centers This pocket guide reflects recommended regimens found in CDC’s Sexually Transmitted Infections Treatment Guidelines, 2021. This summary is intended as a source of clinical guidance. When more than one therapeutic regimen is recommended, the sequence is in alphabetical order unless the choices for therapy are prioritized based on efficacy, cost, or convenience. The recommended regimens should be used primarily; alternative regimens can be considered in instances of substantial drug allergy or other contraindications. An important component of STI treatment is partner management. Providers can arrange for the evaluation and treatment of sex partners either directly or with assistance from state and local health departments. Complete guidelines can be viewed online at https://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment/. This booklet has been reviewed by CDC in July 2021. Accessible version: https://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment-guidelines/default.htm Bacterial Vaginosis Risk Category