PATIENT INFORMATION LEAFLET Genital Warts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Expanding the Role of Dermatology at the World Health Organization and Beyond

EDITORIAL A Seat at the Big Table: Expanding the Role of Dermatology at the World Health Organization and Beyond y patient can’t breathe. From across Kaposi’s sarcoma, seborrheic dermatitis, her- the busy, open ward, you can see the pes zoster, scabies, papular pruritic eruption, Mplaques of Kaposi’s sarcoma riddling eosinophilic folliculitis, tinea, molluscum, drug her skin. The impressive woody edema has reactions, and oral candidiasis (World Health enlarged her legs to the size of small tree trunks. Organization, in press). These conditions have We don’t have access to confirmatory pulmo- a high prevalence in developing countries, but nary testing in Kenya, but she probably wouldn’t many lack internationally agreed-on standards survive a bronchoscopy anyway. of care. This deficit led to inconsistent and some- When she dies six hours later, we can be pret- times dangerous treatment approaches or lack of ty sure that it is her pulmonary Kaposi’s sarcoma, essential drugs. Critically, dermatologists were along with her underlying HIV, that killed her. involved at all levels of the guideline-develop- Her family tells us that she had dark spots on ment process, including Cochrane reviews of the her skin and swelling in her legs for more than literature, guideline development and review, a year before she presented to the hospital. Like and additional funding for the project from many of our patients in East Africa, she sought the International Foundation for Dermatology help from a traditional healer for many months (http://www.ifd.org). before turning to the biomedical health system, Although diseases such as Kaposi’s sarcoma only hours before her death. -

Cutaneous Manifestations of HIV Infection Carrie L

Chapter Title Cutaneous Manifestations of HIV Infection Carrie L. Kovarik, MD Addy Kekitiinwa, MB, ChB Heidi Schwarzwald, MD, MPH Objectives Table 1. Cutaneous manifestations of HIV 1. Review the most common cutaneous Cause Manifestations manifestations of human immunodeficiency Neoplasia Kaposi sarcoma virus (HIV) infection. Lymphoma 2. Describe the methods of diagnosis and treatment Squamous cell carcinoma for each cutaneous disease. Infectious Herpes zoster Herpes simplex virus infections Superficial fungal infections Key Points Angular cheilitis 1. Cutaneous lesions are often the first Chancroid manifestation of HIV noted by patients and Cryptococcus Histoplasmosis health professionals. Human papillomavirus (verruca vulgaris, 2. Cutaneous lesions occur frequently in both adults verruca plana, condyloma) and children infected with HIV. Impetigo 3. Diagnosis of several mucocutaneous diseases Lymphogranuloma venereum in the setting of HIV will allow appropriate Molluscum contagiosum treatment and prevention of complications. Syphilis Furunculosis 4. Prompt diagnosis and treatment of cutaneous Folliculitis manifestations can prevent complications and Pyomyositis improve quality of life for HIV-infected persons. Other Pruritic papular eruption Seborrheic dermatitis Overview Drug eruption Vasculitis Many people with human immunodeficiency virus Psoriasis (HIV) infection develop cutaneous lesions. The risk of Hyperpigmentation developing cutaneous manifestations increases with Photodermatitis disease progression. As immunosuppression increases, Atopic Dermatitis patients may develop multiple skin diseases at once, Hair changes atypical-appearing skin lesions, or diseases that are refractory to standard treatment. Skin conditions that have been associated with HIV infection are listed in Clinical staging is useful in the initial assessment of a Table 1. patient, at the time the patient enters into long-term HIV care, and for monitoring a patient’s disease progression. -

WHO GUIDELINES for the Treatment of Treponema Pallidum (Syphilis)

WHO GUIDELINES FOR THE Treatment of Treponema pallidum (syphilis) WHO GUIDELINES FOR THE Treatment of Treponema pallidum (syphilis) WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data WHO guidelines for the treatment of Treponema pallidum (syphilis). Contents: Web annex D: Evidence profiles and evidence-to-decision frameworks - Web annex E: Systematic reviews for syphilis guidelines - Web annex F: Summary of conflicts of interest 1.Syphilis – drug therapy. 2.Treponema pallidum. 3.Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 4.Guideline. I.World Health Organization. ISBN 978 92 4 154980 6 (NLM classification: WC 170) © World Health Organization 2016 All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization are available on the WHO website (http://www.who.int) or can be purchased from WHO Press, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel.: +41 22 791 3264; fax: +41 22 791 4857; email: [email protected]). Requests for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications – whether for sale or for non-commercial distribution– should be addressed to WHO Press through the WHO website (http://www.who.int/about/licensing/ copyright_form/index.html). The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted and dashed lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. -

Pedianews Volume VI, Issue II the Official Newsletter of the Student Society of Pediatric Advocates (Rxpups) May 2018

1 PediaNews Volume VI, Issue II The Official Newsletter of the Student Society of Pediatric Advocates (RxPups) May 2018 Inside this issue LICEnse to Kill LICEnse to Kill ................... 1-2 Written by: Kirty Patel, Pharm.D. Candidate 2020 Pediatric Idiopathic Thrombocytopenia Purpura ................................. 3-5 It is a dreadful feeling of anxiety when any parent, teacher, or Obesity in Children .......... 6-8 other caregiver discovers lice in a child’s hair. They begin to look back on the past few days and realize that the child has been scratching their Editors head frequently, which is a common sign of head lice. The itching is caused by an allergic reaction to louse saliva. The caregiver may wonder Linda Logan, Pharm.D., BCPS, BCACP why they didn’t previously notice the symptoms but know they can Faculty Advisor contact their local pharmacist with questions, concerns, and guidance Alicia Sanchez, Pharm.D., for the treatment process. PGY2 Pediatric Pharmacy Upon obtaining the phone call, the pharmacist wants to confirm Resident that the child does in fact have lice. The pharmacist explains to the Namita Patel, PharmD caregiver that although lice are small, they can be detected by the Candidate Class of 2019 University of Georgia naked eye. The best way to detect a child’s current state of infestation College of Pharmacy is to examine their scalp for nits (lice eggs) using a magnifying lens and a toothpick comb. Empty nits are lighter in color and further from the scalp, but do not necessarily indicate an active infiltration of lice.1 It is also important to be aware that nits can be misidentified as dandruff, hair spray residue, or even dirt particles that have lodged into the patient’s scalp. -

Scabies, Incomplete Lupus Erythematosus and Henoch-Schonlein Purpura: a Case Report

Scabies, Incomplete Lupus Erythematosus and Henoch-Schonlein Purpura: A Case Report Yang Fang Wu First Aliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University Jing Jing Wang Jinling Hospital Hui Hui Liu First Aliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University Wei Xia Chen First Aliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University Peng Hu ( [email protected] ) First Aliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2144-9806 Case report Keywords: Antinuclear antibody, Henoch-Schonlein purpura, immunoglobulin A, proteinuria, scabies Posted Date: September 18th, 2020 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-63971/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Page 1/8 Abstract BackgroundHenoch-Schonlein purpura (HSP) is a common autoimmune vasculitis in childhood. Although the detailed etiology of HSP remains unknown, several triggers, especially for infectious agents, have been proved to be associated with HSP onset. Case presentation: In the present report, we describe an unusual patient who suffered from HSP and incomplete lupus erythematosus (ILE) on day 8 after scabies, mainly based on nonthrombocytopenic purpura, abdominal pain, medium proteinuria, positive antinuclear antibody (ANA) and skin scrapings. A course of pulse methylprednisolone (10mg/kg/day) was administered for 6 days, followed by oral prednisone (1mg/kg/day). On day 18, the purpuric rashes almost disappeared, whereas medium proteinuria still existed. In this circumstance, a renal biopsy was performed with the informed consent of the parents. According to the criteria proposed by the International Study of Kidney Disease in Children, this patient was classied as class IIIb. The immunouorescence microscopy revealed granular deposits of IgA, IgM and C3 in the glomerular mesangium. -

Epidemiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Scabies in a Dermatology Office

J Am Board Fam Med: first published as 10.3122/jabfm.2017.01.160190 on 6 January 2017. Downloaded from ORIGINAL RESEARCH Epidemiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Scabies in a Dermatology Office Kathryn L. Anderson, MD, and Lindsay C. Strowd, MD Background: Scabies is a neglected skin disease, and little is known about current incidence and treat- ment patterns in the United States. The purpose of this study was to examine demographic data, treat- ment types, success of treatment, and misdiagnosis rate of scabies in an outpatient dermatology clinic. Methods: A retrospective chart review of patients diagnosed with scabies within the past 5 years was performed. Results: A total of 459 charts were identified, with 428 meeting inclusion criteria. Demographic data, diagnostic method, treatment choice, misdiagnosis rate, treatment failure, and itching after scabies are also reported. Children were the largest age group diagnosed with scabies, at 38%. Males (54%) were diagnosed with scabies more than females. The majority of diagnoses were made by visualizing ova, feces, or mites on light microscopy (58%). At the time of diagnosis, 45% of patients had been misdiag- nosed by another provider. Topical permethrin was the most common treatment used (69%), followed by a combination of topical permethrin and oral ivermectin (23%), oral ivermectin (7%), and other treatments (1%). Conclusion: Our findings suggest that more accurate and faster diagnostic methods are needed to limit unnecessary treatment and expedite appropriate therapy for scabies. (J Am -

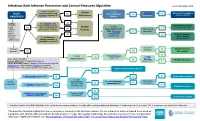

Infectious Rash Infection Prevention and Control Measures Algorithm Issued: November 2019

Infectious Rash Infection Prevention and Control Measures Algorithm Issued: November 2019 Is rash crusted, Contact Is rash RASH scaly or papular and Yes maculopapular? Is Measles Yes Airborne Precautions scabies is suspected? Precautions Yes suspected? Contact site ICP OBSERVED Apular? STAFF: Has scabies been No Perform Droplet Precautions reconsidered & ruled Routine Is rash hand No out if diagnosed as Yes Contact site ICP hygiene psoriasis or eczema? Yes Practices petechial/purpuric Is person >5 Put on AND Neisseria Yes years old? meningitidis gloves Yes No Droplet/Contact for direct suspected? Precautions Is medication/ contact Contact site ICP with lesions allergic reaction or heat rash suspected? Is person Is fever an adult? No Droplet/Contact present? Yes Yes Precautions Is Scarlet Fever Yes Is rash Yes Is Fifth erythematous? suspected? Cover rash if possible. No Disease Routine Practices Person with rash: Perform hand hygiene. suspected? Yes P ut on procedure mask if Measles, Neisseria meningitidis, Chickenpox or disseminated Shingles suspected. If unable to tolerate mask, consider room placement. Airborne/Contact Precautions Yes Is Chickenpox suspected? Yes Yes No Contact Precautions Is rash Is person immune Can rash be Is rash disseminated No (on 3 or more No compromised? covered? vesicular? Is Shingles suspected? Yes Yes dermatomes)? Routine Practices No Is Hand foot and mouth Pediatric AND disease suspected? Yes incontinent? Yes Contact Precautions Algorithm includes initial IP&C highlights only, not treatment recommendations. Consider differential and additional diagnoses; if suspected cause/the answer “No” is not shown, use best clinical judgment. This algorithm includes highlights of some common or consequential infectious rashes. -

Sexually Transmitted Infections–Summary of CDC Treatment

Sexually Transmitted Infections Summary of CDC Treatment Guidelines—2021 Bacterial Vaginosis • Cervicitis • Chlamydial Infections • Epididymitis Genital Herpes Simplex • Genital Warts (Human Papillomavirus) • Gonococcal Infections Lymphogranuloma Venereum • Nongonococcal Urethritis (NGU) • Pediculosis Pubis Pelvic Inflammatory Disease• Scabies • Syphilis • Trichomoniasis U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention National Network of STD Clinical Prevention Training Centers This pocket guide reflects recommended regimens found in CDC’s Sexually Transmitted Infections Treatment Guidelines, 2021. This summary is intended as a source of clinical guidance. When more than one therapeutic regimen is recommended, the sequence is in alphabetical order unless the choices for therapy are prioritized based on efficacy, cost, or convenience. The recommended regimens should be used primarily; alternative regimens can be considered in instances of substantial drug allergy or other contraindications. An important component of STI treatment is partner management. Providers can arrange for the evaluation and treatment of sex partners either directly or with assistance from state and local health departments. Complete guidelines can be viewed online at https://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment/. This booklet has been reviewed by CDC in July 2021. Accessible version: https://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment-guidelines/default.htm Bacterial Vaginosis Risk Category -

Scabies and Impetigo

Scabies and Impetigo Marlyn Mary Mathew Background • Scabies is an intensely pruritic, highly contagious infestation of the skin • Originally, scabies was a term used by the Romans to denote any pruritic skin disease. • In the 17th century, Giovanni Cosimo Bonomo identified the mite as one cause of scabies. Causes • The causative agent for this disease is Sarcoptes scabiei. • The mites that cause scabies burrow into the skin and deposit their eggs, forming a burrow that looks like a pencil mark. • Eggs mature in 21 days. The itchy rash is an allergic response to the mite. Symptoms • Itching, especially at night. • Rashes, especially between the fingers. • Sores (abrasions) on the skin from scratching and digging. • Thin, pencil-mark lines on the skin. • Mites may be more widespread on a baby's skin, causing pimples over the trunk, or small blisters over the palms and soles. • In young children, the head, neck, shoulders, palms, and soles are involved. • In older children and adults, the hands, wrists, genitals, and abdomen are involved. Epidemiology • Scabies infestation occurs worldwide and is very common. • It has been estimated that worldwide, about 300 million cases occur each year. Human scabies has been reported for over 2,500 years. • In the U.S., it is seen frequently in the homeless population but occurs episodically in other populations of all socioeconomic groups as well. Pathophysiology • Direct skin-to-skin contact is the mode of transmission. • Scabies mites are very sensitive to their environment. They can only live off of a host body for 24-36 hours under most conditions. -

Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV) Infection in Men with Genital Ulcer Disease (GUD)—As Observed in Dhaka Medical College Hospital

Original article Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV) Infection in Men with Genital Ulcer Disease (GUD)—as Observed in Dhaka Medical College Hospital Mamun SA1, Chowdhury MAH2, Khan RM3, Sikder MAU4, Hoque MM5. Abstract Introductions Genital herpes clinically underestimated because symptoms or sign occur only in some infection detected serologically. Genital herpes is a contagious recurrent infection caused by Prevalence of HSV subtypes in microbial etiology of Genital the herpes simplex virus (HSV) of which there are two Ulcer Disease (GUD) in men, their association with clinical subtypes HSV-1 and HSV-2. The infection is usually sign, complex of GUD and high-risk behavior were acquired by sexual contact and like other genital ulcer assessed. One hundred men with first episodes of genital diseases increases the risk of HIV transmission and ulcers were prospectively studied for serological evidence of acquisition1-2. Genital herpes clinically underestimated syphilis (RPR and TPHA; T.pallidum IgM and IgG because symptoms or sign occur in less then 40% of the antibodies) and Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) proven infections detected serologically3. Around 90-96% HSV-2 chancroid and herpes. Demographic and epidemiological seropositive women cannot recognize the initial infection4. data were obtained in a standard interview. Positive syphilis Although the virus spread through contact with lesion or serology observed in 11 cases, H. ducreyi detected in 65 secretion but individuals those never have any symptoms cases and Herpes Simplex Virus in 13 cases. Among the and do not know that they are infected with the HSV can PCR proven infections HSV type-2 detected in 7 cases, HSV also transmit the virus to others5. -

School Nurses Confront “The Axis of Evil” Scott A. Norton, MD, MPH, Msc Chief of Dermatology CNMC

School Nurses Confront “The Axis of Evil” Scott A. Norton, MD, MPH, MSc Chief of Dermatology CNMC No financial conflicts of interest 1 Molluscum The Evil Empire for School Nurses Tinea capitis Scabies Head lice School policies by jurisdiction Molluscum contagiosum Maryland VA - VA - VA - (Montgom AAP Red DC Fairfax Arlington Loudoun & PG Book County County County Counties) Not necessary Exclusion not No policy No policy Can attend to exclude routinely but athletes school. from school, recommended; should Lesions not but children for contact cover covered by should not sports/ lesions. clothing participate in activities, can should be contact sports cover lesions covered by with clothing or watertight watertight bandage. bandage 4 http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvrd/molluscum/faq/daycare.htm 6 Molluscum & swimming pools If a person has molluscum, the following recommendations should be followed when swimming: • Cover all visible growths with watertight bandages. • Dispose of all used bandages at home or in a healthcare setting. • Do not share towels, kick boards or other equipment, or toys. • Disinfect kickboards. 7 Tinea capitis (scalp ringworm) Maryland VA - VA - VA - (Montgom & Arlingto AAP Red DC Fairfax Loudoun PG n Book County County Counties) County This is Exclusion Physician's No May return to reportable to until after oral note restrictions school once Divison of treatment stating once child starts Epidemiology initiated. child is not treatment therapy with Disease contagious begins. griseofulvin or Surveillance Can cover terbinafine and lesions to No (with or Investigation prevent direct swimming without exposure pools or selenium gyms. sulfide shampoo). 8 Tinea capitis (scalp ringworm) There is a ringworm outbreak in my child's school/daycare center. -

Communicable Disease Guide

Introduction This guide was developed by the Illinois Department of Public Health (IDPH) to furnish school officials, health care providers and other interested persons with information on the control of communicable diseases. It provides information on 48 common reportable and non-reportable communicable diseases and conditions. More detailed information on many of these diseases can be obtained from the IDPH Web site (www.idph.state.il.us) or from the Web site of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (www.cdc.gov). Both sites have a topics listing that affords easy access to communicable disease-related information. Those diseases or conditions marked with an asterisk must be reported to a local health department or to IDPH. Time frames for reporting to the health authority are designated for each reportable disease. Prompt reporting to the local health authority of all cases of communicable diseases can greatly reduce opportunities for these diseases to be spread. Information related to exclusion from day care and school attendance is noted in bold in the “Control of Case” and “Contact” sections under each disease. For more information, refer to the following IDPH rules and regulations: Control of Communicable Diseases (77 Ill. Adm. Code 690) Child Health Examination Code (77 Ill. Adm. Code 665) Immunization Code (77 Ill. Adm. Code 695) College Immunization Code (77 Ill. Adm. Code 694) Control of Sexually Transmissible Diseases Code (77 Ill. Adm. Code 693) Control of Tuberculosis Code (77 Ill. Adm. Code 696) They can all be accessed through the IDPH Web site, <www.idph.state.il.us/rulesregs/rules-index.htm>.