The Emerging Commercial Suborbital Reusable Launch Vehicle Market

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Capcom Volume 26 Number 3 January/February 2016

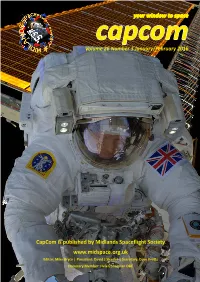

your window to space capcom Volume 26 Number 3 January/February 2016 CapCom is published by Midlands Spaceflight Society www.midspace.org.uk Editor: Mike Bryce | President: David J Shayler | Secretary: Dave Evetts Honorary Member: Helen Sharman OBE Midlands Spaceflight Society: CapCom: Volume 26 no 3 January/February 2016 space news roundup This was the first spacewalk for a British astronaut, but also the first ESA Astronaut Tim Peake Begins sortie for the suit used by Tim Peake, which arrived on the Station in Six-Month Stay On Space Station December. Tim Kopra went first to the far end of the Station’s starboard truss, ESA astronaut Tim Peake, NASA astronaut Tim Kopra and Russian with Tim Peake following with the replacement Sequential Shunt Unit. cosmonaut commander Yuri Malenchenko arrived at the International Swapping the suitcase-sized box was a relatively simple task but one that Space Station, six hours after their launch at 11:03 GMT on 15 needed to be done safely while the clock was ticking. December 2015. To avoid high-voltage sparks, the unit could only be replaced as the The Soyuz TMA-19M spacecraft docked with the Space Station at 17:33 Station flew in Earth’s shadow, giving spacewalkers half an hour to unbolt GMT. The astronauts opened the hatch at 19:58 GMT after checking the the failed power regulator and insert and bolt down its replacement. connection between the seven-tonne Soyuz and the 400-tonne Station was airtight. Tims’ spacewalk With their main task complete, the Tims separated for individual jobs They were welcomed aboard by Russian cosmonauts Mikhail Korniyenko for the remainder of their time outside. -

Virgin Galactic at a Glance

Oct. 17, 2011 Virgin Galactic at a Glance Who: Virgin Galactic, the world’s first commercial spaceline. Vision: Virgin Galactic will provide space access to paying tourism passengers and scientists for research with a smaller environmental impact, lower cost and greater flexibility than any other spaceflight organization, past or present. Once operational, Virgin Galactic aims to fly 500 people in the first year and 30,000 individuals within 10 years. Suborbital Tourism Experience: Through the Virgin Galactic space experience, passengers will be able to leave their seats for several minutes and float in zero-gravity, while enjoying astounding views of space and the Earth stretching approximately 1,000 miles in every direction. Prior to the flight, passengers will go through three days of preparation, medical checks, bonding and G-force acclimatization, all of which is included in the price of the flight. Science/Research/ Education Experience: Virgin Galactic will also host flights dedicated to science, education and research. The vehicles are being built to carry six customers, or the equivalent scientific research payload. The trip into suborbital space offers a unique microgravity platform for researchers. Owners: Sir Richard Branson’s Virgin Group and Aabar Investments PJS History: The 2004 Ansari X Prize called for private sector innovations in the field of manned space exploration. Specifically, participants had to privately fund, design and manufacture a vehicle that could deliver the weight of three people (including one actual person) to suborbital space (altitude of 100 kms). The vehicle had to be 80 percent reusable and fly twice within a two-week period. -

2018-02-13-Yr7-Exec

Federal Aviation Administration Center of Excellence for Commercial Space Transportation Year 7 Annual Report Executive Summary December 31, 2017 www.coe-cst.org EXECUTIVE SUMMARY TABLE OF CONTENTS LETTER FROM THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR ................................................................................ 1 PREFACE .................................................................................................................................. 2 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................... 2 OVERVIEWS ............................................................................................................................. 3 FAA Office of Commercial Space Transportation ........................................................................ 3 FAA Center of Excellence Program .............................................................................................. 3 FAA Center of Excellence for Commercial Space Transportation ............................................... 5 COE CST Year 7 Highlights ..................................................................................................................................... 5 COE CST Year 7 Metrics ......................................................................................................................................... 6 FAA AST Technical Monitors ................................................................................................................................ -

Virgin Galactic Holdings, Inc. (SPCE) Putting the Zero in Zero-G

June 2021 Virgin Galactic Holdings, Inc. (SPCE) Putting the Zero in Zero-G We are short shares of Virgin Galactic Holdings, Inc., often described as the only publicly traded space-tourism company. After going public in October 2019 by way of a merger with a “blank check” company, Virgin Galactic has seen its share price and trading volume soar. It’s become a retail darling, with day traders captivated by images of billionaires donning space suits, blasting off from launchpads, and looking down on the blue marble of Earth. But Virgin Galactic’s $250,000+ commercial “spaceflights” – if they ever actually happen, after some 17 years of delays and disasters – will offer only the palest imitations of these experiences. In lieu of pressurized space suits with helmets – unnecessary since so little time will be spent in the upper atmosphere – the company commissioned Under Armour to provide “high-tech pajamas.” In lieu of vertical takeoff, Virgin’s “spaceship” must cling to the underside of a specialized airplane for the first 45,000 feet up, because its rocket motor is too weak to push through the lower atmosphere on its own. In lieu of the blue-marble vista and life in zero-g, Virgin’s so-called astronauts will at best be able to catch a glimpse of the curvature of Earth and a few minutes of weightlessness before plunging back to ground. This isn’t “tourism,” let alone Virgin’s more grandiose term, “exploration”; it’s closer to a souped- up roller coaster, like the “Drop of Doom” ride at Six Flags. -

Virgin Galactic's Rocket Man the New Yorker.Pdf

Subscribe » A Reporter at Large August 20, 2018 Issue VIRGIN GALACTIC’S ROCKET MAN The ace pilot risking his life to fulll Richard Branson’s billion-dollar quest to make commercial space travel a reality. By Nicholas Schmidle Mark Stucky, the lead test pilot for SpaceShipTwo. “As a Marine Corps colonel once told me,” Stucky said, “ ‘If you want to be safe, go be a shoe salesman at Sears.’ ” Photograph by Dan Winters for The New Yorker t 5 .. on April 5th, Mark Stucky drove to an airstrip in Mojave, California, and gazed at A SpaceShipTwo, a sixty-foot-long craft that is owned by Virgin Galactic, a part of the Virgin Group. Painted white and bathed in oodlight, it resembled a sleek ghter plane, but its mission was to ferry thousands of tourists to and from space. Stucky had piloted SpaceShipTwo on two dozen previous test ights, including three of the four times that it had red its rocket booster, which was necessary to propel it into space. On October 31, 2014, he watched the fourth such ight from mission control; it crashed in the desert, killing his best friend. On this morning, Stucky would be piloting the fth rocket-powered ight, on a new iteration of the spaceship. A successful test would restore the program’s lustre. Stucky walked into Virgin Galactic’s large beige hangar. He is fty-nine and has a loose-legged stroll, tousled salt-and-pepper hair, and sunken, suntanned cheeks. In other settings, he could pass for a retired beachcomber. He wears the smirk of someone who feels certain that he’s having more fun than you are. -

2009 Spaceport News Summary

2009 Spaceport News Summary The 2009 Spaceport News used the above banner for the year. The “Spaceport News” portion picked up a bolder look, starting with the July 24, 2009, issue. Introduction The first issue of the Spaceport News was December 13, 1962. The 1963, 1964 and 1965 Spaceport News were issued weekly. The Spaceport News was issued every two weeks, starting July 7, 1966, until the last issue on February 24, 2014. Spaceport Magazine, a monthly issue, superseded the Spaceport News in April 2014, until the final issue, Jan./Feb. 2020. The two 1962 Spaceport News issues and the issues from 1996 until the final Spaceport Magazine issue, are available for viewing at this website. The Spaceport News issues from 1963 through 1995 are currently not available online. In this Summary, black font is original Spaceport News text, blue font is something I added or someone else/some other source provided, and purple font is a hot link. All links were working at the time I completed this Spaceport News Summary. The Spaceport News writer is acknowledged, if noted in the Spaceport News article. Page 1 From The January 9, 2009, Spaceport News On pages 4 and 5, “Scenes Around Kennedy Space Center”. “Space shuttle Endeavour is being lifted away from the Shuttle Carrier Aircraft, or SCA, at Kennedy Space Center’s Shuttle Landing Facility on Dec. 13. The SCA gave the shuttle a piggyback ride from California, where Endeavour landed Nov. 30, ending the STS-126 mission.” On page 7, “747 took on jumbo task 35 years ago”, by Kay Grinter, Reference Librarian. -

AIAA Houston Horizons Winter 2006/7 Page 1 Page 22

Volume 32, Issue 1 AIAA Houston Section www.aiaa-houston.org Winter 2006/7 Advanced Propulsion Concepts Rendering by Adrian Mann AIAA Houston Horizons Winter 2006/7 Page 1 Page 22 (“DoD Experiments ...”, Continued from page 21) from the surface of the Earth to the surface of the Moon, accelerating at 1.0 E-g during the first half of the course segment and decelerating the ing ways to incorporate new technologies onto the unique vehicle. The last half, and back again; all in under 12-hours without refueling the STS-4 launch in June 1982 carried the first STP shuttle payloads to WarpStar-1’s fuel cells. While on the Moon, the WarpStar-1 could pro- space and since then, has carried over 200 STP payloads including 11 vide heavy lift crane services to Moon-based astronauts that could lift primary DoD payloads. STP conducted experiments aboard the Russian up to 175 lunar metric tonnes. This ~26,500 kg MLT propelled space- Mir space station and boasts the first ISS internal experiment and the craft would be a major advancement over any known spacecraft design first ISS external experiment. These experiments provide the technolo- to date, and should be an inducement to push the development of these gies for the future of military space. A grand example is STP’s launch devices towards the 1.0 N/W specific power class Mach-Lorentz Thrust- of an atomic clock in the 1960s and that experiment evolved into to- ers needed to make it happen. day’s DoD Global Positioning System. -

The Final Countdown – Modern Technology Part 1

1 The Final Countdown – Modern Technology Part 1 “Well, as you guys know, last week it didn’t turn out too well for Al, you know what I’m saying? He had yet another police officer incident! And so when he got released, he had to get a ride home from a taxicab since he didn’t have a driver’s license as we saw last week… Well anyway, on the way home, Al tapped the taxicab driver on the shoulder to ask him a question. But the taxicab driver screamed bloody murder, lost control of the car, nearly hit a bus, went up on a footpath, and stopped just inches from a shop window. And for a second everything went quiet in the cab, then the driver said, ‘Look buddy, don’t ever do that again. You scared the daylights out of me!’ And Al, he apologized and said he didn’t realize that a little tap on the shoulder could scare the guy so much. And the driver calmed down and replied ‘Hey listen, I’m sorry, it’s not really your fault. You see, today is my first day as a taxicab driver – for the last 25 years, I’ve been driving a hearse!’” Now folks, how many of you guys would say that taxicab driver’s fear was justified once you understood the whole context there, you know what I’m saying? Uh huh! He was scared out of his wits, wasn’t he, and rightly so! But that’s right folks, believe it or not, did you know he’s not alone? The Bible says one day the whole planet is going to be scared out of their wits just like that guy at the rapture of the Church! And the Bible says their hearts will actually “fail them with fear,” or in other words, they’ll be dropping like 2 flies with massive heart attacks all over the place because they are so terrified! And that’s because they just entered the 7-year Tribulation and it ain’t no joke! And folks, the time of the Tribulation is not a party. -

21S Macm Henry Holt &

21S Macm Henry Holt & Co. Page 1 of 22 How We Can Win Race, History and Changing the Money Game That's Rigged by Kimberly Jones A breakdown of the economic and social injustices facing Black people and other marginalized citizens inspired by political activist Kimberly Jones' viral video,How Can We Win." "So if I played 400 rounds of monopoly with you and I had to play and give you every dime that I made, and then for 50 years, every time that I played, if you didn't like what I did, you got to burn it like they did in Tulsa and like they did in Rosewood, how can you win? How can you win?" How We Can Win will expand upon statements Kimberly Jones made in a viral video posted in June 2020 following the murder of George Floyd at the hands of police. Through her personal experience, observations, and Monopoly analogy, she illuminates the economic disparities Black Americans have faced for generations and offers ways to fight against a system that is still rigged. Henry Holt & Co On Sale: May 4/21 Author Bio 5.38 x 8.25 • 128 pages 9781250805126 • $31.50 • CL - With dust jacket Kimberly Jones is a former bookseller, and now she hosts the Atlanta Social Science / Ethnic Studies / African-American chapter of the popular Well-Read Black Girl book club. She has worked in film Studies and television with trailblazing figures such as Tyler Perry, Whitney Houston, and 8Ball & MJG. Currently, in addition to writing YA novels, she is a director of feature films and cutting-edge diverse web series. -

Window Opens for Virgin Galactic's Final Round of Testing 20 October 2020, by Susan Montoya Bryan

Window opens for Virgin Galactic's final round of testing 20 October 2020, by Susan Montoya Bryan everything goes well and the engineers sign off, Moses said Virgin Galactic can then move to the next phase, which will involve company mission specialists and engineers being loaded into the passenger cabin. They will evaluate all the hardware, camera settings and which angles will provide the best views. "This is going to be a life-changing experience for folks and we want to make sure we're delivering an A+ ride," he said. More than 600 customers from around the world Credit: Pixabay/CC0 Public Domain have purchased tickets to be launched into the lower fringes of space where they can experience weightlessness and get a view of the Earth below. The suborbital flights are designed to reach an The window for the final round of testing of Virgin altitude of at least 50 miles (80.5 kilometers) before Galactic's rocket-powered spacecraft opens later gliding to a landing. this week as the company inches toward commercial flights. In addition to those who have put down deposits for a ride with Virgin Galactic, several thousands more Virgin Galactic President Mike Moses updated have registered their interest online. New Mexico lawmakers on the progress during a meeting Monday. He said the space tourism The idea to build the spaceport in the New Mexico company already has done nine flights from desert was first hatched years ago by British Spaceport America in southern New Mexico, billionaire Richard Branson and former Gov. Bill including two glide flights by the spaceship. -

September/October 2011 Issue

Volume 37, Issue 2 AIAA Houston Section www.aiaa-houston.org September / October 2011 HubbleCongressman Revisited on NASA’s Pete 50th Olson Anniversary AIAA Houston Section Dinner Meeting Speaker AIAA Houston Section Horizons September / October 2011 Page 1 September / October 2011 T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S From the Chair / AIAA Houston Section Annual Technical Symposium 3 HOUSTON From the Editor 4 Horizons is a bimonthly publication of the Houston Section GRAIL Takes a Roundabout Route to Lunar Orbit, by Dan Adamo 6 of the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics. Congressman Pete Olson, Guest Speaker at our Section’s Dinner Meeting 10 Douglas Yazell Editor “High Altitude”, a Rocket Launch Competition for High School Students 12 Past Editors: Jon Berndt & Dr. Steven Everett Norman Augustine at Rice: The Greatest Obstacle to Human Space Travel 16 Editing team: Don Kulba, Ellen Gillespie, Robert Bere- mand The 1940 Air Terminal Museum at Hobby Airport 17 Regular contributors: Dr. Steven Everett, Don Kulba, Philippe Mairet, Alan Simon, Shen Ge, Scott Lowther Project Leyel, by Jean-Luc Chanel of our French Sister Section 18 Contributors this issue: Daniel Adamo, Glenda Reyes, Dr. Benjamin Longmier, Carlos Salamanca, Jean-Luc 100 Year Starship Symposium, by Douglas Yazell 21 Chanel Shuttle-Derived Personnel Launch Vehicle, by Scott Lowther 22 AIAA Houston Section Executive Council Current Events 24 Staying Informed: Mike Moses (Virgin Galactic), James C. McLane III 25 Daniel Nobles Irene Chan Chair-Elect Secretary Section News (AIAA Houston Section) 26 Sarah Shull John Kostrzewski Page 28: Calendar, Page 29: Cranium Cruncher & NASA SLS Graphic 28 Past Chair Treasurer The Experimental Aircraft Association, EAA Chapter 12 (Houston) 30 Julie Read Vice-Chair, Operations Dr. -

June, 2013 in THIS ISSUE President's

IN THIS ISSUE President’s Message Page 3 Articles Page 12-34 About the Cover Page 4 Letters Page 35-45 Local Reports Page 4-12 In Memoriam Page 45-46 Calendar Page 48 Volume 16 Number 6 (Journal 645) June, 2013 —— OFFICERS —— President Emeritus: The late Captain George Howson President: Phyllis Cleveland ......................................................... 831-622-7747 .................................... [email protected] Vice Pres: Jon Rowbottom ............................................................ 831-595-5275 ....................................... [email protected] Sec/Treas: Leon Scarbrough ......................................................... 707-938-7324 ...................................... [email protected] Membership Tony Passannante ..................................................... 503-658-3860 ................................... [email protected] —— BOARD OF DIRECTORS —— President - Phyllis Cleveland, Vice President - Jon Rowbottom, Secretary Treasurer - Leon Scarbrough Floyd Alfson, Rich Bouska, Sam Cramb, Ron Jersey, Milt Jines, Tony Passannante Walt Ramseur, Bill Smith, Cleve Spring, Larry Wright —— COMMITTEE CHAIRMEN —— Convention Sites. .......................................................... Ron Jersey ............. [email protected] RUPANEWS Manager ............................................. Cleve Spring ......... [email protected] RUPANEWS Editors................................................ Cleve Spring .................. [email protected] Widows Coordinator .............................................