Virgin Galactic's Rocket Man the New Yorker.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Virgin Galactic Announces First Fully Crewed Spaceflight

Virgin Galactic Announces First Fully Crewed Spaceflight Test Flight Window for Unity 22 Mission Opens July 11 Four Mission Specialists to Evaluate Virgin Galactic Astronaut Experience Virgin Galactic Founder Sir Richard Branson Among Mission Specialists First Global Livestream of Virgin Galactic Spaceflight LAS CRUCES, N.M. July 1, 2021 - Virgin Galactic Holdings, Inc. (NYSE: SPCE) (the “Company” or “Virgin Galactic”), a vertically integrated aerospace and space travel company, today announced that the fligHt window for the next rocket-powered test flight of its SpaceShipTwo Unity opens July 11, pending weather and technical checks. The “Unity 22” mission will be the twenty-second flight test for VSS Unity and the Company’s fourth crewed spaceflight. It will also be the first to carry a full crew of two pilots and four mission specialists in tHe cabin, including the Company’s founder, Sir Richard Branson, who will be testing the private astronaut experience. Building on tHe success of the Company’s most recent spaceflight in May, Unity 22 will focus on cabin and customer experience objectives, including: • Evaluating the commercial customer cabin with a full crew, including the cabin environment, seat comfort, the weightless experience, and the views of Earth that the spaceship delivers — all to ensure every moment of the astronaut’s journey maximizes the wonder and awe created by space travel • Demonstrating tHe conditions for conducting human-tended research experiments • Confirming the training program at Spaceport America supports the spaceflight experience For the first time, Virgin Galactic will share a global livestream of the spaceflight. Audiences around the world are invited to participate virtually in tHe Unity 22 test flight and see first-hand the extraordinary experience Virgin Galactic is creating for future astronauts. -

Winners of the 56Th Socal Journalism Awards 2014

Winners of the 56th SoCal Journalism Awards 2014 JOURNALIST OF THE YEAR A1. PRINT (Over 50,000 Circulation) Gene Maddaus, LA Weekly http://bit.ly/1cXc6jk http://bit.ly/1hX6X0F http://bit.ly/1eBLodY http://bit.ly/1hmxVMf Comments: Gene Maddaus did wide-ranging work on a series of stories and was a clear winner in a field fraught with talent. 2nd: Gary Baum, The Hollywood Reporter 3rd: Matthew Belloni, The Hollywood Reporter A2. PRINT (Under 50,000 Circulation) Alfred Lee, Los Angeles Business Journal Comments: Lee's exploration of the wild reaches of the Los Angeles real-estate market displayed an investigative reporter's tenacity, a beat reporter's authoritative research and the breezy style of a deft storyteller. 2nd: Ramin Setoodeh, Variety 3rd: Diana Martinez, San Fernando Valley Sun A3. TELEVISION JOURNALIST Rolando Nichols, MundoFox – Noticias MundoFox http://goo.gl/NadmcU Comments: Good storyteller, with a sense of urgency and place; solid writing and delivery on a mix of stories. Comentarios: Buena narracción, con un sentido de urgencia y lugar. Contiene una gran variedad de reportajes que tienen una redacción y entrega sólida. 2nd: Wendy Burch, KTLA-TV 3rd: Antonio Valverde, KMEX Univision A4. RADIO JOURNALIST Saul Gonzalez, KCRW http://blogs.kcrw.com/whichwayla/2013/11/part-i-william-mulhollands-vision http://blogs.kcrw.com/whichwayla/2013/11/part-2-what-happened-to-the-owens-valley http://blogs.kcrw.com/whichwayla/2013/11/part-3-where-does-your-water-come-from http://blogs.kcrw.com/whichwayla/2013/05/sgt-ryan-craig-and-traumatic-brain-injury Comments: Saul Gonzalez makes the complex understandable in his clear, well- told stories about a variety of topics. -

University of Maryland Men's Basketball Media Guides

>•>--«- H JMl* . T » - •%Jfc» rf*-"'*"' - T r . /% /• #* MARYLAND BASKETBALL 1986-87 1986-87 Schedule . Date Opponent Site Time Dec. 27 Winthrop Home 8 PM 29 Fairleigh Dickinson Home 8 PM 31 Notre Dame Home 7 PM Jan. 3 N.C. State Away 7 PM 5 Towson Home 8 PM 8 North Carolina Away 9 PM 10 Virginia Home 4 PM 14 Duke Home 8 PM 17 Clemson Away 4 PM 19 Buc knell Home 8 PM 21 West Virginia Home 8 PM 24 Old Dominion Away 7:30 PM 28 James Madison Away 7:30 PM Feb. 1 Georgia Tech Away 3 PM 2 Wake Forest Away 8 PM 4 Clemson Home 8 PM 7 Duke Away 4 PM 10 Georgia Tech Home 9 PM 14 North Carolina Home 4 PM 16 Central Florida Home 8 PM 18 Maryland-Baltimore County Home 8 PM 22 Wake Forest Home 4 PM 25 N.C. State Home 8 PM 27 Maryland-Eastern Shore Home 8 PM Mar. 1 Virginia Away 3 PM 6-7-8 ACC Tournament Landover, Maryland 1986-87 BASKETBALL GUIDE Table of Contents Section I: Administration and Coaching Staff 5 Section III: The 1985-86 Season 51 Assistant Coaches 10 ACC Standings and Statistics 58 Athletic Department Biographies 11 Final Statistics, 1985-86 54 Athletic Director — Charles F. Sturtz 7 Game-by-Game Scoring 56 Chancellor — John B. Slaughter 6 Game Highs — Individual and Team 57 Cole Field House 15 Game Leaders and Results 54 Conference Directory 16 Maryland Hoopourri: Past and Present 60 Head Coach — Bob Wade 8 Points Per Possession 58 President — John S. -

Aerospace-America-April-2019.Pdf

17–21 JUNE 2019 DALLAS, TX SHAPING THE FUTURE OF FLIGHT The 2019 AIAA AVIATION Forum will explore how rapidly changing technology, new entrants, and emerging trends are shaping a future of flight that promises to be strikingly different from the modern global transportation built by our pioneers. Help shape the future of flight at the AIAA AVIATION Forum! PLENARY & FORUM 360 SESSIONS Hear from industry leaders and innovators including Christopher Emerson, President and Head, North America Region, Airbus Helicopters, and Greg Hyslop, Chief Technology Officer, The Boeing Company. Keynote speakers and panelists will discuss vertical lift, autonomy, hypersonics, and more. TECHNICAL PROGRAM More than 1,100 papers will be presented, giving you access to the latest research and development on technical areas including applied aerodynamics, fluid dynamics, and air traffic operations. NETWORKING OPPORTUNITIES The forum offers daily networking opportunities to connect with over 2,500 attendees from across the globe representing hundreds of government, academic, and private institutions. Opportunities to connect include: › ADS Banquet (NEW) › AVIATION 101 (NEW) › Backyard BBQ (NEW) › Exposition Hall › Ignite the “Meet”ing (NEW) › Meet the Employers Recruiting Event › Opening Reception › Student Welcome Reception › The HUB Register now aviation.aiaa.org/register FEATURES | APRIL 2019 MORE AT aerospaceamerica.aiaa.org The U.S. Army’s Kestrel Eye prototype cubesat after being released from the International Space Station. NASA 18 30 40 22 3D-printing solid Seeing the far Managing Getting out front on rocket fuel side of the moon drone traffi c Researchers China’s Chang’e-4 Package delivery alone space technology say additive “opens up a new could put thousands manufacturing is scientifi c frontier.” of drones into the sky, U.S. -

101111Ne% 11%01% /111 M6ipirlivfaiwalliellhoelp41 11111

Group W plotting course for its satellite expertise By Bill Dunlap is exceptionally well positioned has two or three sidebands Group W Radio Sales, has to make such a move—better available. We're thinking in a offices in eight top markets and NEW YORK Group W so, for instance, than Turner lot of different directions. will start developing network Radio, the II-station radio Broadcasting's CNN Radio. Where it may take us, if any- sales expertise this month with group taking the first step "As much as I care to say where, Idon't know." he said. its Quality Unwired Radio toward networking this month about it right now" Harris said, What Harris didn't say was Environment (QURE), an un- with an unwired national spot "is that we have alot of satellite that Group W Radio also owns wired commercial network service for its own stations, is at experience with Muzak. We all news or news-talk stations in reaching almost 30 percent of least thinking about providing have 200 downlinks around the such major markets as New the U.S. population. a network news service. United States. We own them all York, Los Angeles, Chicago, "Over the years, we have While Group W Radio Presi- and we're in the process of Philadelphia and Boston and continued to look at where dent Dick Harris plays down enlarging them. that its parent company owns 'there might be a place for us in the likelihood of such aventure "Because of our television half of Satellite News Channels, networking," Harris said. -

Burt Rutan Got His Educational Start at Cal Poly

California Polytechnic State University Sept. 29, 2004 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Teresa Hendrix Public Affairs (805) 756-7266 Media Advisory: Burt Rutan Got His Educational Start at Cal Poly To: News, science, higher education, engineering and feature writers and editors From: Cal Poly -- California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo, California Re: SpaceShipOne designer, Voyager designer Burt Rutan If you are working on biography stories or feature stories about aeronautical design pioneer Burt Rutan, you may want to mention Rutan is a graduate of Cal Poly’s nationally-recognized College of Engineering. Burt Rutan graduated from Cal Poly in 1965 with a bachelor’s degree in aeronautical engineering. His Senior Project won the national student paper competition of the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics that year. Rutan was awarded Cal Poly's first honorary doctorate in 1987. Rutan's SpaceShipOne made history again this morning (Sept. 29) attaining a height of 67 miles during a flight over the Mojave Desert. Piloted by Mike Melvill, SpaceShipOne again landed safely. Watch the launch on the Ansari X-Prize Web site:http://web1-xprize.primary.net/launch.php Read about it in the Los Angeles Times. In its maiden spaceflight n June 2004, the craft landed safely in the Mojave Desert after flying into space, reaching an altitude of 62.5 miles. Rutan has partnered with Microsoft's Paul Allen to create the first private aircraft to travel into space in a quest to claim the $10 million prize in the Ansari X-Flight competition. This week, British billionaire Richard Branson announced plans to buy a fleet of Rutan's aircraft to begin offering commercial flights to the edge of space. -

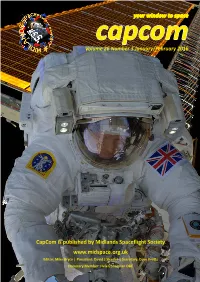

Capcom Volume 26 Number 3 January/February 2016

your window to space capcom Volume 26 Number 3 January/February 2016 CapCom is published by Midlands Spaceflight Society www.midspace.org.uk Editor: Mike Bryce | President: David J Shayler | Secretary: Dave Evetts Honorary Member: Helen Sharman OBE Midlands Spaceflight Society: CapCom: Volume 26 no 3 January/February 2016 space news roundup This was the first spacewalk for a British astronaut, but also the first ESA Astronaut Tim Peake Begins sortie for the suit used by Tim Peake, which arrived on the Station in Six-Month Stay On Space Station December. Tim Kopra went first to the far end of the Station’s starboard truss, ESA astronaut Tim Peake, NASA astronaut Tim Kopra and Russian with Tim Peake following with the replacement Sequential Shunt Unit. cosmonaut commander Yuri Malenchenko arrived at the International Swapping the suitcase-sized box was a relatively simple task but one that Space Station, six hours after their launch at 11:03 GMT on 15 needed to be done safely while the clock was ticking. December 2015. To avoid high-voltage sparks, the unit could only be replaced as the The Soyuz TMA-19M spacecraft docked with the Space Station at 17:33 Station flew in Earth’s shadow, giving spacewalkers half an hour to unbolt GMT. The astronauts opened the hatch at 19:58 GMT after checking the the failed power regulator and insert and bolt down its replacement. connection between the seven-tonne Soyuz and the 400-tonne Station was airtight. Tims’ spacewalk With their main task complete, the Tims separated for individual jobs They were welcomed aboard by Russian cosmonauts Mikhail Korniyenko for the remainder of their time outside. -

Richard Branson Becomes 1St Billionaire to Fly to Space

BENNETT, COLEMAN & CO. LTD. | ESTABLISHED 1838 | TIMESOFINDIA.COM | NEW DELHI I consider myself (the) best and I believe that I am STUDENT EDITION ➤ Learn more on how to ➤ Experts share the best, otherwise I wouldn't be talking confidently manage stress, as a coun- simple yoga tips to about winning Slams and making history. But TUESDAY, JULY 13, 2021 TODAY’S seller explains anxiety balance your body, whether I'm the greatest of all time or not, I leave that Newspaper in Education management mind and soul debate to other people. I said before that it's very difficult to EDITION compare the eras of tennis. But I am extremely hon- PAGE 2 PAGE 3 oured to definitely be part of the conversation NOVAK DJOKOVIC Grand CLICK HERE: PAGE 1 AND 2 Slam No 20 for Djokovic ovak Djokovic tied Roger Federer and HISTORY SCRIPTED! Rafael Nadal by claiming his 20th Grand SlamN title on Sunday, coming back to beat Matteo Berrettini 6-7 (4), 6-4, 6-4, 6-3 in the Wimbledon final. The No 1-ranked Djokovic earned a third consecutive champi- Richard Branson becomes onship at the All England Club and sixth overall. He adds that to nine titles at the Australian Open, three at the US Open and two at the French Open to equal his two rivals for 1st billionaire to fly to space the most majors won by a man in tennis history. The 34-year-old from Serbia is now the only man since Rod Laver in 1969 to win the first three major tournaments in a season. -

A Practical Guide Second Edition

TOURISTS in SPACE A Practical Guide Second Edition Erik Seedhouse Tourists in Space A Practical Guide Other Springer-Praxis books of related interest by Erik Seedhouse Tourists in Space: A Practical Guide 2008 ISBN: 978-0-387-74643-2 Lunar Outpost: The Challenges of Establishing a Human Settlement on the Moon 2008 ISBN: 978-0-387-09746-6 Martian Outpost: The Challenges of Establishing a Human Settlement on Mars 2009 ISBN: 978-0-387-98190-1 The New Space Race: China vs. the United States 2009 ISBN: 978-1-4419-0879-7 Prepare for Launch: The Astronaut Training Process 2010 ISBN: 978-1-4419-1349-4 Ocean Outpost: The Future of Humans Living Underwater 2010 ISBN: 978-1-4419-6356-7 Trailblazing Medicine: Sustaining Explorers During Interplanetary Missions 2011 ISBN: 978-1-4419-7828-8 Interplanetary Outpost: The Human and Technological Challenges of Exploring the Outer Planets 2012 ISBN: 978-1-4419-9747-0 Astronauts for Hire: The Emergence of a Commercial Astronaut Corps 2012 ISBN: 978-1-4614-0519-1 Pulling G: Human Responses to High and Low Gravity 2013 ISBN: 978-1-4614-3029-2 SpaceX: Making Commercial Spacefl ight a Reality 2013 ISBN: 978-1-4614-5513-4 Suborbital: Industry at the Edge of Space 2014 ISBN: 978-3-319-03484-3 Erik Seedhouse Tourists in Space A Practical Guide Second Edition Dr. Erik Seedhouse, Ph.D., FBIS Sandefjord Norway SPRINGER-PRAXIS BOOKS IN SPACE EXPLORATION ISBN 978-3-319-05037-9 ISBN 978-3-319-05038-6 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-05038-6 Springer Cham Heidelberg New York Dordrecht London Library of Congress Control Number: 2014937810 1st edition: © Praxis Publishing Ltd, Chichester, UK, 2008 © Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2014 This work is subject to copyright. -

National Journalism Awards

George Pennacchio Carol Burnett Michael Connelly The Luminary The Legend Award The Distinguished Award Storyteller Award 2018 ELEVENTH ANNUAL Jonathan Gold The Impact Award NATIONAL ARTS & ENTERTAINMENT JOURNALISM AWARDS LOS ANGELES PRESS CLUB CBS IN HONOR OF OUR DEAR FRIEND, THE EXTRAORDINARY CAROL BURNETT. YOUR GROUNDBREAKING CAREER, AND YOUR INIMITABLE HUMOR, TALENT AND VERSATILITY, HAVE ENTERTAINED GENERATIONS. YOU ARE AN AMERICAN ICON. ©2018 CBS Corporation Burnett2.indd 1 11/27/18 2:08 PM 11TH ANNUAL National Arts & Entertainment Journalism Awards Los Angeles Press Club Awards for Editorial Excellence in A non-profit organization with 501(c)(3) status Tax ID 01-0761875 2017 and 2018, Honorary Awards for 2018 6464 Sunset Boulevard, Suite 870 Los Angeles, California 90028 Phone: (323) 669-8081 Fax: (310) 464-3577 E-mail: [email protected] Carper Du;mage Website: www.lapressclub.org Marie Astrid Gonzalez Beowulf Sheehan Photography Beowulf PRESS CLUB OFFICERS PRESIDENT: Chris Palmeri, Bureau Chief, Bloomberg News VICE PRESIDENT: Cher Calvin, Anchor/ Reporter, KTLA, Los Angeles TREASURER: Doug Kriegel, The Impact Award The Luminary The TV Reporter For Journalism that Award Distinguished SECRETARY: Adam J. Rose, Senior Editorial Makes a Difference For Career Storyteller Producer, CBS Interactive JONATHAN Achievement Award EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR: Diana Ljungaeus GOLD International Journalist GEORGE For Excellence in Introduced by PENNACCHIO Storytelling Outside of BOARD MEMBERS Peter Meehan Introduced by Journalism Joe Bell Bruno, Freelance Journalist Jeff Ross MICHAEL Gerri Shaftel Constant, CBS CONNELLY CBS Deepa Fernandes, Public Radio International Introduced by Mariel Garza, Los Angeles Times Titus Welliver Peggy Holter, Independent TV Producer Antonio Martin, EFE The Legend Award Claudia Oberst, International Journalist Lisa Richwine, Reuters For Lifetime Achievement and IN HONOR OF OUR DEAR FRIEND, THE EXTRAORDINARY Ina von Ber, US Press Agency Contributions to Society CAROL BURNETT. -

Virgin Galactic at a Glance

Oct. 17, 2011 Virgin Galactic at a Glance Who: Virgin Galactic, the world’s first commercial spaceline. Vision: Virgin Galactic will provide space access to paying tourism passengers and scientists for research with a smaller environmental impact, lower cost and greater flexibility than any other spaceflight organization, past or present. Once operational, Virgin Galactic aims to fly 500 people in the first year and 30,000 individuals within 10 years. Suborbital Tourism Experience: Through the Virgin Galactic space experience, passengers will be able to leave their seats for several minutes and float in zero-gravity, while enjoying astounding views of space and the Earth stretching approximately 1,000 miles in every direction. Prior to the flight, passengers will go through three days of preparation, medical checks, bonding and G-force acclimatization, all of which is included in the price of the flight. Science/Research/ Education Experience: Virgin Galactic will also host flights dedicated to science, education and research. The vehicles are being built to carry six customers, or the equivalent scientific research payload. The trip into suborbital space offers a unique microgravity platform for researchers. Owners: Sir Richard Branson’s Virgin Group and Aabar Investments PJS History: The 2004 Ansari X Prize called for private sector innovations in the field of manned space exploration. Specifically, participants had to privately fund, design and manufacture a vehicle that could deliver the weight of three people (including one actual person) to suborbital space (altitude of 100 kms). The vehicle had to be 80 percent reusable and fly twice within a two-week period. -

Broadcasting: Feb 18 Reaching Over 117,000 Readers Every Week 60Th Year 1991

Broadcasting: Feb 18 Reaching over 117,000 readers every week 60th Year 1991 TELEVISION / 38 RADIO / 43 BUSINESS / 54 TECHNOLOGY / 64 Fox gears up in -house Operators endorse Em : roadcasting Fiber -satellite pact: production; network chiefs NAB's DAB objectives, r . ncial Vyvx to backhaul sports bemoan sponsor skittishness question its methods tightropeghtrope for IDB- Hughes FES 1 9 1991 F &F Team Scores A Super Bowl "Three- Peat :' F &F remote facilities teams have gone to the last three Super Bowls ... and come away with a winner every time. From editing and support equipment to Jumbotron production to live feeds overseas, F &F t scored every time. So whenever you need mobile units or location facilities for sports, entertainment, or teleconferencing, call the F &F team. You'll get a super production. Productions, Inc. A subsidiary of Hubbard Broadcasting. Inc. 9675 4th Street North, St. Petersburg, FL 33702 813/576 -7676 800/344 -7676 609LA NI 31(1.0._ PIl w3W WVNONINNfl3 (1 31V1S VNVICNI SlV Ia3S 16/a.W )I(1 +7£0f'8VI213S6081h 9/..5 119I C-f **, * * :^*=`** *::*AM ) IndÏaflapolis 3 - A. Broadcasting i Feb 18 THIS WEEK 27 / MORE INPUT ON endorsed the association's plan to back the Eureka 147 FIN -SYN DAB system and to serve White House Chief of as U.S. licensing agent, other Staff John Sununu weighs in broadcasters have on the fin -syn battle, reservations about the action. underscoring President Last week, at two separate Bush's interest in a meetings in Washington -the deregulatory solution to the Radio Operators Caucus issue.