Contractual Arrangements Applicable to Creators: Law and Practice of Selected Member States

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Genre Channel Name Channel No Hindi Entertainment Star Bharat 114 Hindi Entertainment Investigation Discovery HD 136 Hindi Enter

Genre Channel Name Channel No Hindi Entertainment Star Bharat 114 Hindi Entertainment Investigation Discovery HD 136 Hindi Entertainment Big Magic 124 Hindi Entertainment Colors Rishtey 129 Hindi Entertainment STAR UTSAV 131 Hindi Entertainment Sony Pal 132 Hindi Entertainment Epic 138 Hindi Entertainment Zee Anmol 140 Hindi Entertainment DD National 148 Hindi Entertainment DD INDIA 150 Hindi Entertainment DD BHARATI 151 Infotainment DD KISAN 152 Hindi Movies Star Gold HD 206 Hindi Movies Zee Action 216 Hindi Movies Colors Cineplex 219 Hindi Movies Sony Wah 224 Hindi Movies STAR UTSAV MOVIES 225 Hindi Zee Anmol Cinema 228 Sports Star Sports 1 Hindi HD 282 Sports DD SPORTS 298 Hindi News ZEE NEWS 311 Hindi News AAJ TAK HD 314 Hindi News AAJ TAK 313 Hindi News NDTV India 317 Hindi News News18 India 318 Hindi News Zee Hindustan 319 Hindi News Tez 326 Hindi News ZEE BUSINESS 331 Hindi News News18 Rajasthan 335 Hindi News Zee Rajasthan News 336 Hindi News News18 UP UK 337 Hindi News News18 MP Chhattisgarh 341 Hindi News Zee MPCG 343 Hindi News Zee UP UK 351 Hindi News DD UP 400 Hindi News DD NEWS 401 Hindi News DD LOK SABHA 402 Hindi News DD RAJYA SABHA 403 Hindi News DD RAJASTHAN 404 Hindi News DD MP 405 Infotainment Gyan Darshan 442 Kids CARTOON NETWORK 449 Kids Pogo 451 Music MTV Beats 482 Music ETC 487 Music SONY MIX 491 Music Zing 501 Marathi DD SAHYADRI 548 Punjabi ZEE PUNJABI 562 Hindi News News18 Punjab Haryana Himachal 566 Punjabi DD PUNJABI 572 Gujrati DD Girnar 589 Oriya DD ORIYA 617 Urdu Zee Salaam 622 Urdu News18 Urdu 625 Urdu -

Film Financing and Television Programming: a Taxation Guide

Now in its eighth edition, KPMG LLP’s (“KPMG”) Film Financing and Television Programming: A Taxation Guide (the “Guide”) is a fundamental resource for film and television producers, attorneys, tax executives, and finance executives involved with the commercial side of film and television production. The guide is recognized as a valued reference tool for motion picture and television industry professionals. Doing business across borders can pose major challenges and may lead to potentially significant tax implications, and a detailed understanding of the full range of potential tax implications can be as essential as the actual financing of a project. The Guide helps producers and other industry executives assess the many issues surrounding cross-border business conditions, financing structures, and issues associated with them, including film and television development costs and rules around foreign investment. Recognizing the role that tax credits, subsidies, and other government incentives play in the financing of film and television productions, the Guide includes a robust discussion of relevant tax incentive programs in each country. The primary focus of the Guide is on the tax and business needs of the film and television industry with information drawn from the knowledge of KPMG International’s global network of member firm media and entertainment Tax professionals. Each chapter focuses on a single country and provides a description of commonly used financing structures in film and television, as well as their potential commercial and tax implications for the parties involved. Key sections in each chapter include: Introduction A thumbnail description of the country’s film and television industry contacts, regulatory bodies, and financing developments and trends. -

Ethnic Media and Identity Construction: the Representation of Women in the an Ethnic Newspaper in South Africa

E-ISSN 2281-4612 Academic Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies Vol 2 No 8 ISSN 2281-3993 MCSER Publishing, Rome-Italy October 2013 Ethnic Media and Identity Construction: The Representation of Women in the An Ethnic Newspaper in South Africa D. Soobben Lecturer: Department Media, Languages & Communication Faculty of Arts, Durban University of Technology Tel: +27 (0) 31-3736617, e-mail: [email protected] V.P. Rawjee Snr. Lecturer and HOD: Department of Public Relations Management Faculty of Management Sciences Durban University of Technology Tel: +27 (0) 31-3736826, e-mail: [email protected] Doi:10.5901/ajis.2013.v2n8p697 Abstract Media are powerful agents of socialisation. Through representation, media helps in constructing and reproducing gender identities. The representation of how women are constructed by the media has travelled due to globalization. The 2006 Global Media Monitoring Project reveals that women are under-represented in news. The media are therefore construed as constructing gender subjectivity. For example, women are literally absent in news, politics and economics and hardly ever appear as spokespersons or as field experts. These subjective representations are often framed though the lenses of the media producers and are influenced by the political economy of the media. Media are therefore seen as representing a distorted version of women. Gallagher (2004), however states that in South Africa, the process of changing gender in the newsroom has started and media audiences, texts and institutions have changed, largely due to the persistent gender advocacy. Based on this, this paper sets out to investigate how Indian women are represented in a South African newspaper targeted at a cross-national ethnic readership. -

A Channel Guide

Intelsat is the First MEDIA Choice In Africa Are you ready to provide top media services and deliver optimal video experience to your growing audiences? With 552 channels, including 50 in HD and approximately 192 free to air (FTA) channels, Intelsat 20 (IS-20), Africa’s leading direct-to- home (DTH) video neighborhood, can empower you to: Connect with Expand Stay agile with nearly 40 million your digital ever-evolving households broadcasting reach technologies From sub-Saharan Africa to Western Europe, millions of households have been enjoying the superior video distribution from the IS-20 Ku-band video neighborhood situated at 68.5°E orbital location. Intelsat 20 is the enabler for your TV future. Get on board today. IS-20 Channel Guide 2 CHANNEL ENC FR P CHANNEL ENC FR P 947 Irdeto 11170 H Bonang TV FTA 12562 H 1 Magic South Africa Irdeto 11514 H Boomerang EMEA Irdeto 11634 V 1 Magic South Africa Irdeto 11674 H Botswana TV FTA 12634 V 1485 Radio Today Irdeto 11474 H Botswana TV FTA 12657 V 1KZN TV FTA 11474 V Botswana TV Irdeto 11474 H 1KZN TV Irdeto 11594 H Bride TV FTA 12682 H Nagravi- Brother Fire TV FTA 12562 H 1KZN TV sion 11514 V Brother Fire TV FTA 12602 V 5 FM FTA 11514 V Builders Radio FTA 11514 V 5 FM Irdeto 11594 H BusinessDay TV Irdeto 11634 V ABN FTA 12562 H BVN Europa Irdeto 11010 H Access TV FTA 12634 V Canal CVV International FTA 12682 H Ackermans Stores FTA 11514 V Cape Town TV Irdeto 11634 V ACNN FTA 12562 H CapeTalk Irdeto 11474 H Africa Magic Epic Irdeto 11474 H Capricorn FM Irdeto 11170 H Africa Magic Family Irdeto -

Supreme Court of India Miscellaneous Matters to Be Listed on 08-09-2021

SUPREME COURT OF INDIA MISCELLANEOUS MATTERS TO BE LISTED ON 08-09-2021 NMD ADVANCE LIST - AL/94/2021 SNo. Case No. Petitioner / Respondent Petitioner/Respondent Advocate 1 SLP(C) No. 33403/2016 NOIDA TOLL BRIDGE COMPANY LTD. KARANJAWALA & CO. XI Versus FEDERATION OF NOIDA RESIDENTS WELFARE RAVINDRA KUMAR[CAVEAT], ASSOCIATION AND ORS AND ORS. DIKSHA RAI[CAVEAT], ARCHANA PATHAK DAVE[CAVEAT], AP & J CHAMBERS[CAVEAT], RAKESH MISHRA[R-3], ANIL KATIYAR[R-3], PRADEEP MISRA[R-5], SENTHIL JAGADEESAN[R-9] RESPONDENT-IN-PERSON[INT] IA No. 32116/2017 - APPLICATION FOR IMPLEADMENT IA No. 59736/2017 - APPROPRIATE ORDERS/DIRECTIONS IA No. 170774/2018 - APPROPRIATE ORDERS/DIRECTIONS IA No. 11143/2020 - CLARIFICATION/DIRECTION IA No. 107853/2017 - CLARIFICATION/DIRECTION IA No. 2/2017 - EXEMPTION FROM FILING O.T. IA No. 2/2017 - EXTENSION OF TIME IA No. 6278/2017 - IA FOR IMPLEADMENT, DIRECTION IA No. 93748/2016 - IMPLEADMENT IA No. 91160/2017 - INTERVENTION APPLICATION IA No. 15386/2018 - INTERVENTION/IMPLEADMENT IA No. 91157/2017 - PERMISSION TO APPEAR AND ARGUE IN PERSON IA No. 75084/2019 - PERMISSION TO PLACE ADDITIONAL FACTS AND GROUNDS IA No. 77337/2021 - VACATING STAY IA No. 19850/2020 - VACATING STAY 1.1 Connected NEW OKHLA INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY RAVINDRA KUMAR[P-1] SLP(C) No. 8060/2019 XIV Versus NOIDA TOLL BRIDGE COMPANY LTD. AND ANR. KARANJAWALA & CO.[R-1] FOR ADMISSION and I.R. and IA No.51044/2019- EXEMPTION FROM FILING C/C OF THE IMPUGNED JUDGMENT and IA No.51053/2019-PERMISSION TO FILE LENGTHY LIST OF DATES IA No. 51044/2019 - EXEMPTION FROM FILING C/C OF THE IMPUGNED JUDGMENT IA No. -

Optik TV Channel Listing Guide 2020

Optik TV ® Channel Guide Essentials Fort Grande Medicine Vancouver/ Kelowna/ Prince Dawson Victoria/ Campbell Essential Channels Call Sign Edmonton Lloydminster Red Deer Calgary Lethbridge Kamloops Quesnel Cranbrook McMurray Prairie Hat Whistler Vernon George Creek Nanaimo River ABC Seattle KOMODT 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 Alberta Assembly TV ABLEG 843 843 843 843 843 843 843 843 ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● AMI-audio* AMIPAUDIO 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 AMI-télé* AMITL 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 AMI-tv* AMIW 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 APTN (West)* ATPNP 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 — APTN HD* APTNHD 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 — BC Legislative TV* BCLEG — — — — — — — — 843 843 843 843 843 843 843 843 843 CBC Calgary* CBRTDT ● ● ● ● ● 100 100 100 ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● CBC Edmonton* CBXTDT 100 100 100 100 100 ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● CBC News Network CBNEWHD 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 CBC Vancouver* CBUTDT ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 CBS Seattle KIRODT 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 CHEK* CHEKDT — — — — — — — — 121 121 121 121 121 121 121 121 121 Citytv Calgary* CKALDT ● ● ● ● ● 106 106 106 ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● — Citytv Edmonton* CKEMDT 106 106 106 106 106 ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● — Citytv Vancouver* -

Know About Your Packege (1).Xlsx

List of Free to Air Channels Provided by us S.No. Channel Name Category Genres 1 HDS Bhajan Hindi Channel Local Channel 2 HDS Bollywood Hindi Channel Local Channel 3 HDS Cinema Hindi Channel Local Channel 4 HDS Devbhoomi Regional Local Channel 5 HDS Haryanvi Regional Local Channel 6 HDS Kids Hindi Channel Local Channel 7 HDS Movie Hindi Channel Local Channel 8 HDS Paigam Regional Local Channel 9 HDS Punjabi Regional Local Channel 10 HDS South Hindi Channel Local Channel 11 HDS Action Hindi Channel Local Channel 12 HDS Hollywood Hindi Channel Local Channel 13 HDS Uttrakhand Regional Local Channel 14 HTV Classic Hindi Channel Local Channel 15 Information Hindi Channel Local Channel 16 Taal Hindi Channel Local Channel 17 9X Jalwa Hindi Channel MUSIC PACK 18 9X Jhakaas Regional MUSIC PACK 19 9X Tashan Music Channel MUSIC PACK 20 9XM Hindi Channel MUSIC PACK 21 Aakaash Bangla Regional Bengali 22 Aalmi Samay Regional Urdu Pack 23 Aashtha Bhajan Hindi Channel BHAKTI PACK 24 Aastha Hindi Channel BHAKTI PACK 25 ABP Ananda Regional Other 26 ABP Asmita Regional News Channel 27 ABP Ganga Hindi Channel HINDI NEWS 28 ABP Majha Regional Other 29 ABP News Hindi Channel HINDI NEWS 30 Air Rainbow Regional Radio Channel 31 Andy Haryana Regional Other 32 Anjan Music Channel MUSIC PACK 33 Arihant Tv Hindi Channel BHAKTI PACK 34 B4U Bhojpuri Hindi Channel Hindi Cinema 35 B4U Kadak Hindi Channel Hindi Cinema 36 B4U Movies Hindi Channel Hindi Cinema 37 B4U Music Hindi Channel MUSIC PACK 38 Balle Balle Regional Panjabi Channel 39 Bflix Movies Hindi Channel Hindi -

Channel Listing Fibe Tv Current As of June 18, 2015

CHANNEL LISTING FIBE TV CURRENT AS OF JUNE 18, 2015. $ 95/MO.1 CTV ...................................................................201 MTV HD ........................................................1573 TSN1 HD .......................................................1400 IN A BUNDLE CTV HD ......................................................... 1201 MUCHMUSIC ..............................................570 TSN RADIO 1050 .......................................977 GOOD FROM 41 CTV NEWS CHANNEL.............................501 MUCHMUSIC HD .................................... 1570 TSN RADIO 1290 WINNIPEG ..............979 A CTV NEWS CHANNEL HD ..................1501 N TSN RADIO 990 MONTREAL ............ 980 ABC - EAST ................................................... 221 CTV TWO ......................................................202 NBC ..................................................................220 TSN3 ........................................................ VARIES ABC HD - EAST ..........................................1221 CTV TWO HD ............................................ 1202 NBC HD ........................................................ 1220 TSN3 HD ................................................ VARIES ABORIGINAL VOICES RADIO ............946 E NTV - ST. JOHN’S ......................................212 TSN4 ........................................................ VARIES AMI-AUDIO ....................................................49 E! .........................................................................621 -

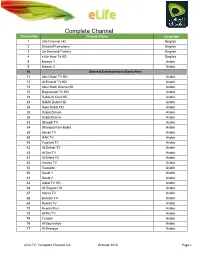

Complete Channel List October 2015 Page 1

Complete Channel Channel No. List Channel Name Language 1 Info Channel HD English 2 Etisalat Promotions English 3 On Demand Trailers English 4 eLife How-To HD English 8 Mosaic 1 Arabic 9 Mosaic 2 Arabic 10 General Entertainment Starts Here 11 Abu Dhabi TV HD Arabic 12 Al Emarat TV HD Arabic 13 Abu Dhabi Drama HD Arabic 15 Baynounah TV HD Arabic 22 Dubai Al Oula HD Arabic 23 SAMA Dubai HD Arabic 24 Noor Dubai HD Arabic 25 Dubai Zaman Arabic 26 Dubai Drama Arabic 33 Sharjah TV Arabic 34 Sharqiya from Kalba Arabic 38 Ajman TV Arabic 39 RAK TV Arabic 40 Fujairah TV Arabic 42 Al Dafrah TV Arabic 43 Al Dar TV Arabic 51 Al Waha TV Arabic 52 Hawas TV Arabic 53 Tawazon Arabic 60 Saudi 1 Arabic 61 Saudi 2 Arabic 63 Qatar TV HD Arabic 64 Al Rayyan HD Arabic 67 Oman TV Arabic 68 Bahrain TV Arabic 69 Kuwait TV Arabic 70 Kuwait Plus Arabic 73 Al Rai TV Arabic 74 Funoon Arabic 76 Al Soumariya Arabic 77 Al Sharqiya Arabic eLife TV : Complete Channel List October 2015 Page 1 Complete Channel 79 LBC Sat List Arabic 80 OTV Arabic 81 LDC Arabic 82 Future TV Arabic 83 Tele Liban Arabic 84 MTV Lebanon Arabic 85 NBN Arabic 86 Al Jadeed Arabic 89 Jordan TV Arabic 91 Palestine Arabic 92 Syria TV Arabic 94 Al Masriya Arabic 95 Al Kahera Wal Nass Arabic 96 Al Kahera Wal Nass +2 Arabic 97 ON TV Arabic 98 ON TV Live Arabic 101 CBC Arabic 102 CBC Extra Arabic 103 CBC Drama Arabic 104 Al Hayat Arabic 105 Al Hayat 2 Arabic 106 Al Hayat Musalsalat Arabic 108 Al Nahar TV Arabic 109 Al Nahar TV +2 Arabic 110 Al Nahar Drama Arabic 112 Sada Al Balad Arabic 113 Sada Al Balad -

At Harvard College

Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology AT HARVARD COLLEGE Vol. LXXXII, No. 5 THE FULGORINA OF BARRO COLORADO AND OTHER PARTS OF PANAMA By Z. P. Metcalf College of Agriculture and Engineering of the University of North Carolina With Twenty-thhee Plates CAMBRIDGE, MASS., U.S.A. PRINTED FOR THE MUSEUM October, 1938 No. 5.— The Fulgorina of Barro Colorado and Other Parts of Panama By Z. P. Metcalf In the summer of 1924 Mr. Nathan Banks, Curator of Insects of the Museum of Comparative Zoology of Harvard University spent some time collecting insects on Barro Colorado Island, Gatun Lake, Canal Zone. Among these was a large number of Fulgorids. These he turned over to me for study. At about the same time Mr. C. H. Curran, Assistant Curator of Insect Life of the American Museum of Natural History called my attention to a number of Fulgorids in their collec- tions from Barro Colorado. Still later Mr. Paul Oman, Curator of Homoptera of the United States National Museum, separated the material in their collections from Barro Colorado and sent it to me for study. These three collections together with a considerable collection which I have from Central and South America formed the nucleus for a report which would supplement the reports of Distant and Fowler in the Biologia. I suggested this to Mr. Banks and he agreed to its publication. CLASSIFICATION USED In the present report I have used the general classification developed recently by Muir (1930c) and have supplemented this general classi- fication with special works in more restricted groups especially the work of Melichar, Muir, Schmidt and Jacobi. -

KPMG FLASH NEWS 18 Decemberkpmg 2015 in India

KPMG FLASH NEWS 18 DecemberKPMG 2015 in India The Indian company constitutes dependent agent permanent establishment of the US television company Background The taxpayer appointed NGC India as its distributor to distribute its television channels and also to procure advertisements for telecasting in Recently, the Mumbai Bench of the Income-tax the channels. Hence, the taxpayer generates two Appellate Tribunal (the Tribunal) in the case of NGC 1 streams of revenues from India, i.e. (a) Fee for Network Asia LLC (the taxpayer) held that the Indian giving distribution rights for telecasting of its group company of a foreign company has been channels and (b) Advertisement revenues. habitually exercising in India an authority to conclude contracts on behalf of the foreign company which are During the assessment year (AY) 2007-08, two binding on the foreign company. Therefore, the Indian agreements entered by the taxpayer with NGC company has been treated as a dependent agent India in respect of advertisement revenues. As per permanent establishment (DAPE) in India under Article the old agreement, the taxpayer has given 5(4)(a) of the India-USA tax treaty (tax treaty). commission at 15 per cent to NGC India and The Tribunal also held that ‘advertisement air time’ does retained 85 per cent of the advertisement revenue. not fall under the category of ‘goods’. The Tribunal As per the new agreement, it has received fixed observed that the right to procure advertisements for amount from NGC India for giving contract of particular airtime, though capable of being transferred, procuring advertisements. cannot be consumed/used by the buyer of the right, in The taxpayer claimed that both types of income the absence of any assistance from the taxpayer by way were not taxable in India and accordingly did not of telecasting the same in the television channels. -

Choose the Channels You Want with Fibe TV

Choose the channels you want with Fibe TV. Add individual channels to your Starter or Basic package. Channel Name Channel Group Price Channel Name Channel Group Price Channel Name Channel Group Price A&E PrimeTime 1 $ 2.99 CMT PrimeTime 2 $ 4.00 DistracTV Apps on TV $ 4.99 South Asia Premier Aapka Colors $ 6.00 CNBC News $ 4.00 DIY Network Explore $ 1.99 Package CNN PrimeTime 1 $ 7.00 documentary Cinema $ 1.99 ABC Seattle Time Shift West $ 2.99 Comedy Gold Replay $ 1.99 Dorcel TV More Adult $21.99 ABC Spark Movie Picks $ 1.99 Cooking Movie Picks $ 1.99 DTOUR PrimeTime 2 $ 1.99 Action Movie Flicks $ 1.99 CosmoTV Life $ 1.99 DW (Deutsch+) German $ 5.99 AMC Movie Flicks $ 7.00 Cottage Life Places $ 1.99 E! Entertainment $ 6.00 American Heroes Channel Adventure $ 1.99 CP24 Information $ 8.00 ESPN Classic Sports Enthusiast $ 1.99 Animal Planet Kids Plus $ 1.99 Crave Apps on TV $ 7.99 EWTN Faith $ 2.99 A.Side TV Medley $ 1.99 Crave + Movies + HBO Crave + Movies + $18/6 Pack Exxxtasy Adult $21.99 ATN South Asia Premier $16.99 HBO Fairchild Television Chinese $19.99 Package Crime + Investigation Replay $ 1.99 B4U Movies South Asia Package $ 6.00 Family Channel (East/West) Family $ 2.99 CTV BC Time Shift West $ 2.99 BabyTV Kids Plus $ 1.99 Family Jr. Family $ 2.99 CTV Calgary Time Shift West $ 2.99 BBC Canada Places $ 1.99 Fashion Television Channel Lifestyle $ 1.99 CTV Halifax Time Shift East $ 2.99 BBC Earth HD HiFi $ 1.99 Fight Network Sports Fans $ 1.99 CTV Kitchener Time Shift East $ 2.99 BBC World News Places $ 1.99 Food Network Life $ 1.99 CTV Moncton Time Shift East $ 2.99 beIN Sports Soccer & Wrestling $14.99 Fox News News $ 1.99 CTV Montreal Time Shift East $ 2.99 BET Medley $ 2.99 Fox Seattle Time Shift West $ 2.99 CTV News Channel News $ 2.