Robert Drewe and John Kinsell

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ghosts of Ned Kelly: Peter Carey’S True History and the Myths That Haunt Us

Ghosts of Ned Kelly: Peter Carey’s True History and the myths that haunt us Marija Pericic Master of Arts School of Communication and Cultural Studies Faculty of Arts The University of Melbourne November 2011 Submitted in total fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts (by Thesis Only). Abstract Ned Kelly has been an emblem of Australian national identity for over 130 years. This thesis examines Peter Carey’s reimagination of the Kelly myth in True History of the Kelly Gang (2000). It considers our continued investment in Ned Kelly and what our interpretations of him reveal about Australian identity. The paper explores how Carey’s departure from the traditional Kelly reveals the underlying anxieties about Australianness and masculinity that existed at the time of the novel’s publication, a time during which Australia was reassessing its colonial history. The first chapter of the paper examines True History’s complication of cultural memory. It argues that by problematising Kelly’s Irish cultural memory, our own cultural memory of Kelly is similarly challenged. The second chapter examines Carey’s construction of Kelly’s Irishness more deeply. It argues that Carey’s Kelly is not the emblem of politicised Irishness based on resistance to imperial Britain common to Kelly narratives. Instead, he is less politically aware and also claims a transnational identity. The third chapter explores how Carey’s Kelly diverges from key aspects of the Australian heroic ideal he is used to represent: hetero-masculinity, mateship and heroic failure. Carey’s most striking divergence comes from his unsettling of gender and sexual codes. -

Stgd/Ned Kelly A4 . March

NED KELLY Study Guide by Robert Lewis and Geraldine Carrodus ED KELLY IS A RE-TELLING OF THE WELL-KNOWN STORY OF THE LAST AUSTRALIAN OUTLAW. BASED ON THE NOVEL OUR SUNSHINE BY ROBERT DREWE, THE FILM REPRESENTS ANOTHER CHAPTER IN NAUSTRALIA’S CONTINUING FASCINATION WITH THE ‘HERO’ OF GLENROWAN. The fi lm explores a range of themes The criminals are at large and are armed including justice, oppression, relation- and dangerous. People are encouraged ships, trust and betrayal, family loyalty, not to resist the criminals if they see the meaning of heroism and the nature them, but to report their whereabouts of guilt and innocence. It also offers an immediately to the nearest police sta- interesting perspective on the social tion. structure of rural Victoria in the nine- teenth century, and the ways in which • What are your reactions to this traditional Irish/English tensions and four police was searching for the known story? hatreds were played out in the Austral- criminals. The police were ambushed by • Who has your sympathy? ian colonies. the criminals and shot down when they • Why do you react in this way? tried to resist. Ned Kelly has the potential to be a very This ‘news flash’ is based on a real valuable resource for students of History, The three murdered police have all left event—the ambush of a party of four English, Australian Studies, Media and wives and children behind. policemen by the Kelly gang in 1878, at Film Studies, and Religious Education. Stringybark Creek. Ned Kelly killed three The gang was wanted for a previous of the police, while a fourth escaped. -

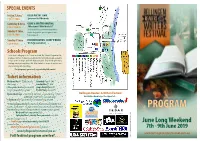

PROGRAM 7Th - 9Th June 2019 7Th - June Weekend Long

SPECIAL EVENTS Friday 7 June BELLO POETRY SLAM 7:30-11:30pm Sponsored by Officeworks Saturday 8 June CRIME & MYSTERY WRITING 2:30-3:30pm & ‘Whodunnit? Who Wrote It?’ Six of Australia’s best crime/mystery authors Sunday 9 June explore this popular specialist genre in two 9:30-10:30pm featured panels Sunday 9 June IN CONVERSATION: KERRY O’BRIEN 6:30-8:00pm ‘A Life In Journalism’ Schools Program In the days leading up to the Festival weekend, the Schools Program will be placing a number of experienced authors into both primary and secondary schools in the Bellingen and Coffs Harbour regions. They will be presenting exciting interactive workshops that offer students a chance to explore new ways of writing and storytelling. This program is generously supported by Officeworks Ticket information Weekend Pass** $160 (Saturday Saturday Pass** $90 and Sunday) Sunday Pass** $90 (Please Note: Weekend Pass does NOT Single Event Pass $25 include Friday night Poetry Slam) Poetry Slam (Friday) $15 Morris Gleitzman - Special Kids & Parents session (Sunday, 9:30am) - Bellingen Readers & Writers Festival Adult $20 / Child* $5 (15 years and under) Gratefully acknowledges the support of ~ * Children under age 10 must be accompanied by an adult ** Concessions available for: Pensioner, Healthcare and Disability card holders, and Students – Available only for tickets purchased at the Waterfall PROGRAM Way Information Centre, Bellingen (evidence of status must be sighted) Weekend Pass concession $140 art+design: Walsh Pingala Saturday Pass & Sunday Pass concession each $80 All tickets available online at - • Trybooking - www.trybooking.com/458274 June Long Weekend Or in person from - • Waterfall Way Information Centre, Bellingen 7th - 9th June 2019 www.bellingenwritersfestival.com.au © 2019 www.bellingenwritersfestival.com.au Full festival program overleaf . -

Neelima Kanwar* 70

47 Area Studies : A Journal of International Studies & Analyses Prejudice and Acceptance (?): Issues of Integration in Australia 69. The Deccan Chronicle, October 10, 2011. NEELIMA KANWAR* 70. The New Indian Express, July 13, 2011 71. Strategic Digest, May 2011, p. 399. Look here You have never seen this country, It's not the way you thought it was, Look again. (Al Purdy) Contemporary Australia is a land of varied cultures inhabited by the Aboriginals, the Whites and non-White immigrants. The Indigenous people of Australia have been dominated by the Whites since the very arrival of the Whites. They have not only been colonized but have been permanently rendered as a marginalized minority group. Even in the present times; their predicament has not changed much. They are still under the control of the Whites while limiting the Aboriginal people to the periphery of the continent have occupied the central position. Since the early 1970s, Australia has experienced multiple waves of immigration from Southeast Asia which have transformed the character of Australian society more radically than the earlier post-war immigration from Southern Europe. These non- white/coloured immigrants have remained sympathetic towards the original inhabitants in their new found home. However, the social positioning of these coloured people has somehow followed the same pattern as of the Aboriginals. They * Dr. Neelima Kanwar, Associate Professor, Department of English, International Centre for Distance Education and Open Learning (ICDEOL), Himachal Pradesh University, Shimla. 49 Area Studies : A Journal of International Studies & Analyses Prejudice and Acceptance (?): Issues of Integration in Australia 50 too have been pressurized to abandon and forget their own “ …this country shall remain forever the home of the native culture in an alien land which they have sought to make descendants of those people who came here in peace in order to their second home. -

EN 383: AUSTRALIAN LITERATURE COURSE SPECIFICATIONS Title EN 383: AUSTRALIAN LITERATURE Course Coordinator Dr. Sharon Clarke C

EN 383: AUSTRALIAN LITERATURE COURSE SPECIFICATIONS Title EN 383: AUSTRALIAN LITERATURE Course Coordinator Dr. Sharon Clarke COURSE SYNOPSIS This course is designed to introduce students to the literature of Australia through an eclectic collection of texts covering diverse forms and genres of writing. A critical exploration of these texts will be undertaken in terms of Australia's cultural formation/ evolution. Aspects and contexts of history, geographical location, urban and rural landscape, climate, and people will inform this exploration. Where possible, relevant guest speakers will be invited to address classes. Critical material will be introduced to discussions in which all students are expected to participate. Where appropriate, videotaped footage will also be used and discussed as another form of critical appraisal of a text. FORMAT For this course, formal lectures, group tutorials and seminar presentations have been organised. Attendance at all sessions is compulsory. While lectures will offer certain readings of texts - as well as providing the historical, geographical, social and environmental background to these texts - such readings should be considered by no means exclusive. In seminar presentations, students will be encouraged to explore other meanings and to develop their own textually-based and research-based analytical and evaluative skills. All students will be expected to contribute to all class discussions and therefore need to prepare for each class by completing the reading designated in the following schedule, and by allowing all possible time for the consideration of issues raised in preparatory material provided in advance. Each student will also be expected to partake in a seminar. This presentation should take the form of a prepared informed address, developed around a particular aspect of a text, chosen from the list marked "Presentation Topics. -

Resurrecting Ned Kelly LYN INNES

Resurrecting Ned Kelly LYN INNES In a review of Peter Carey’s True History of the Kelly Gang, the poet Peter Porter commented that the three most potent icons in Australian popular history were Ned Kelly, Phar Lap, and Donald Bradman.1 Of these Ned Kelly has the longest history, and has undergone numerous revivals and reconfigurations. One might also argue that he was the least successful of the three; he was a man who saw himself as a victim of empire, class, race, and the judicial system. At least that is how Kelly presents himself in The Jerilderie Letter, and many of those who have written about him affirm that this view was justified. So the question is why and in what ways Ned Kelly has become so potent; why cannot Australians let him die? And what does he mean to Australians, or indeed the rest of the world, today? This essay will glance briefly at some early representations of Kelly, before discussing in more detail Peter Carey’s revival of Kelly, and considering the significance of that revival in the present. Kelly and his gang became legends in their lifetimes, and promoted themselves in this light. Joe Byrne, one of the gang members, is named as the author of “The Ballad of Kelly’s Gang”, sung to the tune of “McNamara’s Band”: Oh, Paddy dear, and did you hear the news that’s going ‘round? On the head of bold Ned Kelly they have placed two thousand pound, And on Steve Hart, Joe Byrne and Dan two thousand more they’d give; But if the price was doubled, boys the Kelly Gang would live. -

I'm a MAMIL…A Middle-Aged Man in Lycra

December 2015 | January 2016 Beauty & Ghosts Robert Drewe’s Broome Smoked Trout Waffles Breakfast Martini-Style Cat, Garden, House Do We Expect Too Much? Giving Money to the Kids How it Affects Your Pension Twitter, Facebook, Instagram Join the Social Network Roly Sussex “I’m a MAMIL…a Middle-Aged Man in Lycra” editor With four prime ministers in five the damage we’re doing to our Have a fabulous summer. years, mid-term assassinations country over the longer term. Sarah Saunders are starting to define Australian These killings are poll-driven – so Editor politics. It’s something for which why now would a smart politician [email protected] Japan – think five prime ministers make unpopular decisions early in five years from 2007 – has in a first term. always been notorious. These days, it seems the courage To be honest, I’m not a fan. Sure, of conviction is a luxury no-one Publisher the treachery of knifing a sitting seeking longevity can afford. It’s not National Seniors Australia prime minister; the ugly braying the electorate that they answer to A.B.N. 89 050 523 003 from the margins; and the raw but their colleagues – all of whom, ISSN 1835–5404 emotion borne out of an ultimate well-schooled in the Machiavellian Editor humiliation make for great TV. arts, harbour their own ambitions. Sarah Saunders Its mediaeval-ness is thoroughly My hope for 2016 is that we shift s.saunders@ modern. We all have opinions, we away from this hollowness to nationalseniors.com.au all have platforms and we want something authentic and enduring. -

Mimesis, Movies and Media: the 3 Annual Conference of The

Mimesis, Movies and Media: The 3rd Annual Conference of the Australian Girard Seminar 18-19 January 2013 University of Western Sydney Paper Abstracts Session 1 Dr. John O’Carroll (Charles Sturt University), “The All-Too-Human Machine: Mimesis, Scapegoat, Medium”. Media theorists of social crisis frequently have recourse to work in the tradition of Stanley Cohen’s Folk Devils and Moral Panics (1972) to explain the bursts of scapegoating that have, since the advent of mass media in the early twentieth century, dominated public life. More recent social media phenomena, such as hate-pages, trolling and flaming have revealed the inadequacy of such approaches, and indeed, that these approaches never were adequate even to what they purported initially to explain. This is so on two levels, the first of which concerns the way such mechanisms work anthropologically, the second, in terms of how these systems are themselves now interpenetrated with techniques and technologies of mediation. Cohen’s book can be challenged on each of these levels, as the theme of this conference on René Girard and the media suggests. The first challenge arises from Girard’s work because he grasps mimetic behavior not just in the usual terms of copycat imitation, but in terms of acquisitive relations. The second challenge to be posed is more difficult to establish: I draw from a reworked communications tradition extending from Jacques Ellul to Jean Baudrillard. Such a synthesis enables a grasp of how such mimesis is embedded in communications techniques themselves. The trajectory of this inquiry as a whole makes it a shuttle-work of sorts. -

Representation and Reinterpretations of Australia's War in Vietnam

Vietnam Generation Volume 3 Number 2 Australia R&R: Representation and Article 1 Reinterpretations of Australia's War in Vietnam 1-1991 Australia R&R: Representation and Reinterpretations of Australia's War in Vietnam Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/vietnamgeneration Part of the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation (1991) "Australia R&R: Representation and Reinterpretations of Australia's War in Vietnam," Vietnam Generation: Vol. 3 : No. 2 , Article 1. Available at: http://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/vietnamgeneration/vol3/iss2/1 This Complete Volume is brought to you for free and open access by La Salle University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vietnam Generation by an authorized editor of La Salle University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ON THIS SITE WILL BE ERECTED A MEMORIAL FOR THOSE WHO DIED & SERVED IN THE VIETNAM WAR maoKJwmiiMisanc? wmmEsnp jnauKi«mmi KXm XHURST rw svxr Representations and Reinterpretations of Australia's War in Vietnam Edited by Jeff Doyle & Jeffrey Grey Australia ReJR Representations and Reinterpretations o f Australia's war in Vietnam Edited by Jeff Doyle & Jeffrey Grey V ietnam Generation, I n c & Burning Cities Press Australia ReJR is published as a Special Issue of Vietnam Generation Vietnam Generation was founded in 1988 to promote and encourage interdisciplinary study of the Vietnam War era and the Vietnam War generation. The journal is published by Vietnam Generation, Inc., a nonprofit corporation devoted to promoting scholarship on recent history and contemporary issues. Vietnam Generation, Inc. Vice-President President Secretary, Treasurer HERMAN BEAVERS KALI TAL CYNTHIA FUCHS General Editor Newsletter Editor Technical Assistance KALI TAL DAN DUFFY LAWRENCE E HUNTER Advisory Board NANCY AN1SFIELD MICHAEL KLEIN WILLIAM J. -

The Influence of Peter Carey's True History of the Kelly Gang: Repositioning the Ned Kelly Narrative in Australian Popular Culture

<<Please read the copyright notice at the end of this article>> Nathanael O'Reilly: The Influence of Peter Carey's True History of the Kelly Gang: Repositioning the Ned Kelly Narrative in Australian Popular Culture Author: Nathanael O'Reilly Title: The Influence of Peter Carey's True History of the Kelly Gang: Repositioning the Ned Kelly Narrative in Australian Popular Culture Journal: Journal of Popular Culture Imprint: 2007, Volume 40, Number 3, June, Pages 488-502 GROWING UP IN AUSTRALIA DURING THE NINETEEN-SEVENTIES, I became aware of the legendary bushranger1 Ned Kelly at an early age; stories of his exploits were taught in primary school, and children often emulated Kelly and his gang in the school playground. The story of Ned Kelly is an integral part of the Australian childhood. Long before learning other national narratives, such as the stories of the explorers Burke and Wills, the cricket-player Sir Donald Bradman, or the slaughter at Gallipoli during the First World War, we learned about Ned Kelly. However, while the Kelly narrative held a prominent position in educational and social discourse, it did not occupy the dominant position in popular culture that it has attained in recent years. Ned Kelly is currently a dominant figure in the Australian national consciousness, largely due to the commercial and critical success of Peter Carey's novel True History of the Kelly Gang, which repositioned the Kelly narrative firmly at the center of Australian popular culture and created a commercial and cultural environment conducive to the production of further revisions of the narrative. -

Australian Literature and the War in Vietnam Peter Pierce

Vietnam Generation Volume 3 Number 2 Australia R&R: Representation and Article 9 Reinterpretations of Australia's War in Vietnam 1-1991 "The unnF y Place": Australian Literature and the War in Vietnam Peter Pierce Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/vietnamgeneration Part of the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Pierce, Peter (1991) ""The unnF y Place": Australian Literature and the War in Vietnam," Vietnam Generation: Vol. 3 : No. 2 , Article 9. Available at: http://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/vietnamgeneration/vol3/iss2/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by La Salle University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vietnam Generation by an authorized editor of La Salle University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 'The Funny Place': Australian Literature and the W ar in Vietnam. Peter Pierce Men who fought in the Australian and American forces in the Vietnam War were never persuaded for long of a good reason why they were there. Most, however, soon found others who experienced enough to tell them where they were. In Nasho (1984),1 a novel by the Australian conscript Michael Frazer (who did not see service in Vietnam), it is quickly explained to the protagonist. Turner, a journalist with the supposed Army Information Corps, that, It’s not called the funny place because Bob Hope does a concert there eveiy year. It’s really a strange war. It’s a politicians' war, not a soldiers’ war. If the Americans declared war on the Antarctic penguins, Australia would have a battalion there. -

The Australian Beachspace: Flagging the Spaces of Australian Beach Texts

THE AUSTRALIAN BEACHSPACE: FLAGGING THE SPACES OF AUSTRALIAN BEACH TEXTS Elizabeth Ellison Bachelor of Creative Industries (Hons) Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Creative Writing and Literary Studies Discipline School of Media, Entertainment, and Creative Arts Creative Industries Faculty Queensland University of Technology 2013 Supervisory Team Principal Supervisor Dr Lesley Hawkes Creative Writing and Literary Studies Associate Supervisor Dr Sean Maher Film, Television and New Media ii The Australian Beachspace: flagging the spaces of Australian beach texts Keywords Australian beaches, Australian film, Australian literature, Australian studies, gender studies, Indigenous film, Indigenous literature, spatial studies, Thirdspace, beachspace The Australian Beachspace: flagging the spaces of Australian beach texts iii Abstract The Australian beach is a significant component of the Australian culture and a way of life. The Australian Beachspace explores existing research about the Australian beach from a cultural and Australian studies perspective. Initially, the beach in Australian studies has been established within a binary opposition. Fiske, Hodge, and Turner (1987) pioneered the concept of the beach as a mythic space, simultaneously beautiful but abstract. In comparison, Meaghan Morris (1998) suggested that the beach was in fact an ordinary or everyday space. The research intervenes in previous discussions, suggesting that the Australian beach needs to be explored in spatial terms as well as cultural ones. The thesis suggests the beach is more than these previously established binaries and uses Soja’s theory of Thirdspace (1996) to posit the term beachspace as a way of describing this complex site. The beachspace is a lived space that encompasses both the mythic and ordinary and more.