Representation and Reinterpretations of Australia's War in Vietnam

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

When Australia Said NO! Fifteen Years Ago, the Australian People Turned Down the Menzies Govt's Bid to Shackle Democracy

„ By ERNIE CAMPBELL When Australia said NO! Fifteen years ago, the Australian people turned down the Menzies Govt's bid to shackle democracy. gE PT E M B E R . 22 is the 15th Anniversary of the defeat of the Menzies Government’s attempt, by referendum, to obtain power to suppress the Communist Party. Suppression of communism is a long-standing plank in the platform of the Liberal Party. The election of the Menzies Government in December 1949 coincided with America’s stepping-up of the “Cold War”. the Communist Party an unlawful association, to dissolve it, Chairmanship of Senator Joseph McCarthy, was engaged in an orgy of red-baiting, blackmail and intimidation. This was the situation when Menzies, soon after taking office, visited the United States to negotiate a big dollar loan. On his return from America, Menzies dramatically proclaimed that Australia had to prepare for war “within three years”. T o forestall resistance to the burdens and dangers involved in this, and behead the people’s movement of militant leadership, Menzies, in April 1950, introduced a Communist Party Dis solution Bill in the Federal Parliament. T h e Bill commenced with a series o f recitals accusing the Communist Party of advocating seizure of power by a minority through violence, intimidation and fraudulent practices, of being engaged in espionage activities, of promoting strikes for pur poses of sabotage and the like. Had there been one atom of truth in these charges, the Government possessed ample powers under the Commonwealth Crimes Act to launch an action against the Communist Party. -

Australian Journal of Emergency Management

Department of Home Affairs Australian Journal of Emergency Management VOLUME 36 NO. 1 JANUARY 2021 ISSN: 1324 1540 NEWS AND VIEWS REPORTS RESEARCH Forcasting and Using community voice Forecasting the impacts warnings to build a new national of severe weather warnings system Pages 11 – 21 Page 50 Page 76 SUPPORTING A DISASTER RESILIENT AUSTRALIA Changes to forcasting and warnings systems improve risk reduction About the journal Circulation The Australian Journal of Emergency Management is Australia’s Approximate circulation (print and electronic): 5500. premier journal in emergency management. Its format and content are developed with reference to peak emergency management Copyright organisations and the emergency management sectors—nationally and internationally. The journal focuses on both the academic Articles in the Australian Journal of Emergency Management are and practitioner reader. Its aim is to strengthen capabilities in the provided under a Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial sector by documenting, growing and disseminating an emergency (CC BY-NC 4.0) licence that allows reuse subject only to the use management body of knowledge. The journal strongly supports being non-commercial and to the article being fully attributed the role of the Australian Institute for Disaster Resilience as a (creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0). national centre of excellence for knowledge and skills development © Australian Institute for Disaster Resilience 2021. in the emergency management sector. Papers are published in Permissions information for use of AJEM content all areas of emergency management. The journal encourages can be found at http://knowledge.aidr.org.au/ajem empirical reports but may include specialised theoretical, methodological, case study and review papers and opinion pieces. -

Report of the Inquiry Into Recognition for Service at the Battle of Long

INQUIRY INTO UNRESOLVED RECOGNITION ISSUES FOR THE BATTLE OF LONG TAN LETTER OF TRANSMISSION Inquiry into Unresolved Recognition Issues for the Battle of Long Tan The Hon Dr Mike Kelly AM MP Parliamentary Secretary for Defence Support Parliament House Canberra ACT 2600 Dear Dr Kelly I am pleased to present the report of the Defence Honours and Awards Tribunal on the Inquiry into Unresolved Recognition Issues for the Battle of Long Tan. The inquiry was conducted in accordance with the Terms of Reference. The panel of the Tribunal that conducted the inquiry arrived unanimously at the findings and recommendations set out in its report. Yours sincerely Professor Dennis Pearce, AO Chair 3 September 2009 2 CONTENTS LETTER OF TRANSMISSION...................................................................................................................... 2 TERMS OF REFERENCE............................................................................................................................. 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY............................................................................................................................... 5 RECOMMENDATIONS................................................................................................................................. 7 REPORT........................................................................................................................................................ 8 ESTABLISHMENT OF INQUIRY AND TERMS OF REFERENCE ............................................................................ -

The Vietnam War an Australian Perspective

THE VIETNAM WAR AN AUSTRALIAN PERSPECTIVE [Compiled from records and historical articles by R Freshfield] Introduction What is referred to as the Vietnam War began for the US in the early 1950s when it deployed military advisors to support South Vietnam forces. Australian advisors joined the war in 1962. South Korea, New Zealand, The Philippines, Taiwan and Thailand also sent troops. The war ended for Australian forces on 11 January 1973, in a proclamation by Governor General Sir Paul Hasluck. 12 days before the Paris Peace Accord was signed, although it was another 2 years later in May 1975, that North Vietnam troops overran Saigon, (Now Ho Chi Minh City), and declared victory. But this was only the most recent chapter of an era spanning many decades, indeed centuries, of conflict in the region now known as Vietnam. This story begins during the Second World War when the Japanese invaded Vietnam, then a colony of France. 1. French Indochina – Vietnam Prior to WW2, Vietnam was part of the colony of French Indochina that included Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam. Vietnam was divided into the 3 governances of Tonkin, Annam, and Cochinchina. (See Map1). In 1940, the Japanese military invaded Vietnam and took control from the Vichy-French government stationing some 30,000 troops securing ports and airfields. Vietnam became one of the main staging areas for Japanese military operations in South East Asia for the next five years. During WW2 a movement for a national liberation of Vietnam from both the French and the Japanese developed in amongst Vietnamese exiles in southern China. -

Darwin 5 • New Accessions – Alice Springs 6 • Spotlight on

June 2005 No.29 ISSN 1039 - 5180 From the Director NT History Grants Welcome to Records Territory. In this edition we bring news of The Northern Territory History Grants for 2005 were advertised in lots of archives collecting activity and snapshots of the range of The Australian and local Northern Territory newspapers in mid- archives in our collections including a spotlight on Cyclone Tracy March this year. The grants scheme provides an annual series of following its 30th anniversary last December. Over the past few fi nancial grants to encourage and support the work of researchers months the NT Archives Service has been busily supporting who are recording and writing about Northern Territory history. research projects through both our public search room and the The closing date for applications was May 06 2005. NT History Grants program. Details of successful History Grant recipients for 2004 can be On the Government Recordkeeping front, we have passed found on page 10. the fi rst milestone of monitoring agency compliance with the We congratulate the following History Grants recipients for Information Act and have survived the fi rst full year of managing completion of their research projects for which they received part our responsibilities under the Act. Other initiatives have or total assistance from the N T History Grants Program. included the establishment of a records retention and disposal review committee and continued coordination of an upgrade of Robert Gosford – Annotated Chronological Bibliography – Northern the government’s records management system TRIM. Territory Ethnobiology 1874 to 2004 John Dargavel – Persistance and transition on the Wangites-Wagait We are currently celebrating the long awaited implementation reserves, 1892-1976 ( Journal of Northern Territory History Issue No of the archives management system, although there is a long 15, 2004, pp 5 – 19) journey ahead to load all of the relevant information to assist us and our researchers. -

AUSTRALIA DAY HOMEWORK CONTRACT – Week 1

HOMEWORK CONTRACT – Week 1 Write your spelling words each day using LOOK – SAY – COVER – WRITE - CHECK Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday AUSTRALIA DAY On the 26th January 1788, Captain Arthur 1) When is Australia Day ? Phillip and the First Fleet arrived at Sydney ______________________________________ Cove. The 26th January is celebrated each 2) Why do we celebrate Australia Day? year as Australia Day. This day is a public ______________________________________ holiday. There are many public celebrations to take part in around the country on 3) What ceremonies take place on Australia Day? Australia Day. Citizenship ceremonies take ______________________________________ place on Australia Day as well as the 4) What are the Australian of the Year and the presentation of the Order of Australia and Order of Australia awarded for? Australian of the Year awards for ______________________________________ outstanding achievement. It is a day of 5) Name this year’s Australian of the Year. great national pride for all Australians. ______________________________________ Correct the following paragraph. Write the following words in Add punctuation. alphabetical order. Read to see if it sounds right. Australia __________________ our family decided to spend australia day at the flag __________________ beach it was a beautiful sunny day and the citizenship __________________ celebrations __________________ beach was crowded look at all the australian ceremonies __________________ flags I said. I had asked my parents to buy me Australian __________________ a towel with the australian flag on it but the First Fleet __________________ shop had sold out awards __________________ Circle the item in each row that WAS NOT invented by Australians. boomerang wheel woomera didgeridoo the Ute lawn mower Hills Hoist can opener Coca-Cola the bionic ear Blackbox Flight Recorder Vegemite ©TeachThis.com.au HOMEWORK CONTRACT – Week 1 Created by TeachThis.com.au Number Facts Problem solving x 4 3 5 9 11 1. -

Newsletter 211997 October 1997

Newsletter 211997 October 1997 Formation of the Duntroon Society P.J. Day An event which occurred nine months before the birth and a preliminary paper reconnaissance by the Team led to the of the Duntroon Society deserves to be recorded even if same conclusion. A detailed site inspection was arranged for 24 only as a footnote to history. I cannot claim it as the to 26 September 1979. A plan to establish a Junior Wing of the moment of conception for, as Major General A.L. (Alan) Command and Staff College at Canungra was the cover for a Morrison (1 945) wrote in Newsletter lN980, the idea of a visit at short notice by three brigadiers. But before the visit it Society was considered as early as 1920. However, the was necessary to consult the Commandant, RMC. event which I shall describe almost certainly induced a birth earlier than might have been the case. Accordingly, on 21 September 1979 we were received by an hospitable but puzzled Commandant. As David Drabsch On Friday, 21 September 1979, the Commandant outlined our task, a range of emotions struggled in the received a visit from three officers forming the 'DBD Study Commandant for expression. However, his self control was Team'. Their visit would probably be described by Alan admirable and he listened in silence. Much to our relief he fully Morrison as a shock rather than an event. appreciated that arguing for the status quo was not an option for us. We noted h~svlews on the matters we had to consider until, The DBD Study Team had its genesis in the controversy finally, he expressed d~sappointmentat the prospect of the RMC surrounding the establishment of the Australian Defence Force moving from Canberra. -

2015 Anne Summers Issue 11 2015

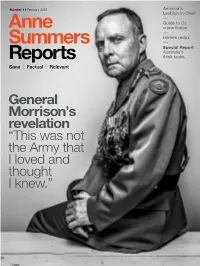

Number 11 February 2015 America’s Lesbian-in-Chief Guide to Oz crime fiction Harlem redux Special Report Australia’s think tanks Sane Factual Relevant General Morrison’s revelation “This was not the Army that I loved and thought I knew.” #11 February 2015 I HOPE YOU ENJOY our first issue for 2015, and our eleventh since we started our digital voyage just over two years ago. We introduce Explore, a new section dealing with ideas, science, social issues and movements, and travel, a topic many of you said, via our readers’ survey late last year, you wanted us to cover. (Read the full results of the survey on page 85.) I am so pleased to be able to welcome to our pages the exceptional mrandmrsamos, the husband-and-wife team of writer Lee Tulloch and photographer Tony Amos, whose piece on the Harlem revival is just a taste of the treats that lie ahead. No ordinary travel writing, I can assure you. Anne Summers We are very proud to publish our first investigative special EDITOR & PUBLISHER report on Australia’s think tanks. Who are they? Who runs them? Who funds them? How accountable are they and how Stephen Clark much influence do they really have? In this landmark piece ART DIRECTOR of reporting, Robert Milliken uncovers how thinks tanks are Foong Ling Kong increasingly setting the agenda for the government. MANAGING EDITOR In other reports, you will meet Merryn Johns, the Australian woman making a splash as a magazine editor Wendy Farley in New York and who happens to be known as America’s Get Anne Summers DESIGNER Lesbian-in-Chief. -

Dungarvan Ceader Leader and SOUTHERN DEMOCRAT for Full Particulars of Rates, Etc

If you want best Test Drive The New STARLET results .... advertise in the Dungarvan Dungarvan Ceader Leader and SOUTHERN DEMOCRAT For full particulars of rates, etc. Circulating throughout the County and City of Waterford, South Tipperary and South-East Cork HORNIBROOKS 'Phone 058/41203 of LISMORE : Tel. 058/54147 Vol. 48. No. 2444 REGISTERED AT THE GENERAL FRIDAY, JANUARY 24, 1986 POST OFFICE AS A NEWSPAPER PRICE 25p (inc. VAT) PBNSMAN TAKES YOU CASUAL TRADERS IN AS LADIES behind the SPOHIGIIT June 18 D-Day For Move FASHIONS PARTY OF THE FUTURE? round about we are aware that MAIN STREET A poll conducted nationwide there is plenty support await- la9t week for a daily paper ing the establishment of a From Dungarvan Square CAPPOQUIN indicated that the new political branch of the new party in the Telephone 058/54125 district and it can only be a The saga of the casual tra now for the legal enforcers to charters. He added that in. the party established by former ders at Grattan Square, Dun- the transition to the new trad- Fianna Fail deputies Des matter of time before that back un the law. negotiations he concentrated ing area at. Davitt's Quay would garvan, and the repeated at- Associating himself with Cllr. more on getting agreement to O'Malley, T.D. and Mary Har- happens. tempts to shift them, made be peaceful. Kyne's remarks, Cllr. Austin move and as the new location The Town Clerk's report was GREAT WINTER T.D., the Progressive With three deputies now in over a long number of years Hallahan added that he was only about 30 yards from ney, which up to this- have proved unanimously adopted and ap- Democrats, had, at that stage, the Dail (since Pearse Wyse thought the £2 charge for tha e Square he was hopeful that proved. -

Two of Us: Shane Withington and Suzette Meade

Upfront I was a neurotic mess by the time the Currawong campaign was won, which makes me wary for Suzette. I always end our calls say- ing, “Look after yourself and don’t burn out.” But she seems to be able to handle the pressure. We get on really well, except she doesn’t answer the phone when I want her to, and when I suggest letting off flares, she doesn’t reply, so it doesn’t happen. But I’ll mention it again, and if it still doesn’t happen, I’ll let flares off without her knowing. UZETTE: I was on maternity leave with Smy second child in 2015 when the NSW government development proposal for 6500 apartments and a retail complex in the Cumberland Hospital precinct reared its head. I went to the North Parramatta Residents Action Group’s first meeting, and was nominated to head the action against the development. Shane was the MC for a Crown land summit at NSW Parliament House. I knew of Shane from when he played nurse Brendan Jones on A Country Practice. Summing up, he said, “We all need to get involved with the Female Factory, because that is too precious to lose.” Afterwards, I thanked him for highlighting our plight in Parramatta. He gave me his num- ber, and said to ring if he could help. I contacted Shane several times, but he was always filming. In 2017, after an Aboriginal land claim had removed a third of the land, a TWO OF US development application was lodged for subdi- STORY BY Rosamund Burton PHOTOGRAPH BY Joshua Morris vision of the site for 2900 units and a retail complex, with 1100 units deferred. -

View Room Judy Green Monitor Productions

sue barnett & associates CELIA IRELAND TRAINING 1998 Practical Aesthetics (Burlington Vermont) 1996 Diploma in Primary Education (Newcastle University) 1990 Post Graduate Certificate Adult T.E.S.O.L (Charles Sturt University) FILM Venice Australian Woman Dragonet Films Dir: Milo Bilbrough Goddess Mary Goddess Productions Pty Ltd Dir: Mark Lamprell Cactus Vesna Barmaid New Town Films Dir: Jasmine Yuen-Carrucan Rogue Gwen Emu Creek Pictures Dir: Greg McLean Australian Rules Liz Black Tidy Town Pictures Dir: Paul Goldman Angst Case Worker Green Light Angst Pty. Ltd My Mother Frank Peggy Intrepid Films Pty Ltd Dir: Mark Lamprell Thank God He Met Lizzie Cheryl Stamen Films Dir: Cherie Nolan Idiot Box Barmaid Dir: David Caesar Floating Life Waitress Dir: Clara Law On Our Selection Sarah Dir: George Whaley Out The Girl (Lead) Dir: Samantha Lang Dallas Doll ABC TELEVISION Five Bedrooms Rhonda Hoodlum Dir: Peter Templeton Total Control Tracey Blackfella Films/ABC Dir: Rachel Perkins Wentworth (Series 7) Liz Fremantle Media Wentworth (Series 6) Liz Fremantle Media Wentworth (Series 5) Liz Fremantle Media Wentworth (Series 4) Liz Fremantle Media Wentworth (Series 3) Liz Fremantle Media Wentworth (Series 2) Liz Fremantle Media Rake (Series 3) Cop ABC Dir: Peter Duncan Redfern Now (Series 2) Nurse Edwards Redfern Pictures Pty Ltd Wentworth Liz Fremantle Media Home and Away Connie Callaghan Seven Network Packed to the Rafters (Series 5) Colleen Burke Seven Network My Place (Series 2) The Bank’s Maid Matchbox Pictures Me and My Monsters Pauline Sticky Pictures Laid Brendan’s Mum ABC TV Bargain Coast Jaqueline Cornerbox Pty Ltd Monster House Mrs. -

It's Taken Almost 49 Years to Uncover Vol 1 No

THE EYES and EARS "FIRST PUBLISHED 22nd JULY 1967 in Nui Dat, South Vietnam” Editor: Paul ‘Dicko’ Dickson email: [email protected] Vol. 9 No. 7 – 31/07/2016 No. 96 Official newsletter of the 131 Locators Association Inc ABN 92 663 816 973 web site: http://www.131locators.org.au Supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs A bit of history has been discovered!!! It’s taken almost 49 years to uncover Vol 1 No IX! This all stared with Barry Guzder sending Grahame Dignam the following email – “Hi Digs, Don’t know if this will make the next E&Es but it’s a good reminder of days gone by! Regards Barry G.” Grahame copied the email to Ed who followed up with Barry as to where the hell did he discover this and here’s his response – “Hi Paul, I had it with all my other Vietnam paraphernalia on returning to Oz in ’68. Put it all away and year and half later sailed to U.K. So mum looked after all that military stuff till I returned in ’75. Just took it all in a box to new house in ’78. Went thru box in 2013, found it and put it into ‘Tracks of the Dragon”. Showed book to friends at bushfire brigade and out it fell! Regards, Barry.” Ed - Bloody amazing “out it fell”, but we are ever so thankful as it now means that Vol 1 No 11 is the only missing issue. Is there anyone else who can perform some magic and produce it? Here’s Barry’s now archived issue - Page 1 of 16 Page 2 of 16 OK, let’s go looking for Vol 1 No IX…someone must have one ferreted away somewhere?? Page 3 of 16 .