Management of Antithrombotic Drugs in Association with Endoscopic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

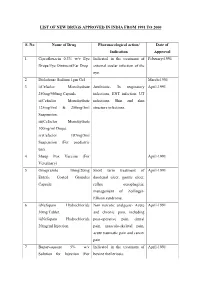

List of New Drugs Approved in India from 1991 to 2000

LIST OF NEW DRUGS APPROVED IN INDIA FROM 1991 TO 2000 S. No Name of Drug Pharmacological action/ Date of Indication Approval 1 Ciprofloxacin 0.3% w/v Eye Indicated in the treatment of February-1991 Drops/Eye Ointment/Ear Drop external ocular infection of the eye. 2 Diclofenac Sodium 1gm Gel March-1991 3 i)Cefaclor Monohydrate Antibiotic- In respiratory April-1991 250mg/500mg Capsule. infections, ENT infection, UT ii)Cefaclor Monohydrate infections, Skin and skin 125mg/5ml & 250mg/5ml structure infections. Suspension. iii)Cefaclor Monohydrate 100mg/ml Drops. iv)Cefaclor 187mg/5ml Suspension (For paediatric use). 4 Sheep Pox Vaccine (For April-1991 Veterinary) 5 Omeprazole 10mg/20mg Short term treatment of April-1991 Enteric Coated Granules duodenal ulcer, gastric ulcer, Capsule reflux oesophagitis, management of Zollinger- Ellison syndrome. 6 i)Nefopam Hydrochloride Non narcotic analgesic- Acute April-1991 30mg Tablet. and chronic pain, including ii)Nefopam Hydrochloride post-operative pain, dental 20mg/ml Injection. pain, musculo-skeletal pain, acute traumatic pain and cancer pain. 7 Buparvaquone 5% w/v Indicated in the treatment of April-1991 Solution for Injection (For bovine theileriosis. Veterinary) 8 i)Kitotifen Fumerate 1mg Anti asthmatic drug- Indicated May-1991 Tablet in prophylactic treatment of ii)Kitotifen Fumerate Syrup bronchial asthma, symptomatic iii)Ketotifen Fumerate Nasal improvement of allergic Drops conditions including rhinitis and conjunctivitis. 9 i)Pefloxacin Mesylate Antibacterial- In the treatment May-1991 Dihydrate 400mg Film Coated of severe infection in adults Tablet caused by sensitive ii)Pefloxacin Mesylate microorganism (gram -ve Dihydrate 400mg/5ml Injection pathogens and staphylococci). iii)Pefloxacin Mesylate Dihydrate 400mg I.V Bottles of 100ml/200ml 10 Ofloxacin 100mg/50ml & Indicated in RTI, UTI, May-1991 200mg/100ml vial Infusion gynaecological infection, skin/soft lesion infection. -

VTE) Cindy Ward, DNP, RN-BC, CMSRN, ACNS-BC

Chronic Complications of Venous Thromboembolism (VTE) Cindy Ward, DNP, RN-BC, CMSRN, ACNS-BC Roanoke, VA Disclosure • The speaker has no conflicts of interest to disclose. Carilion Roanoke Memorial Hospital • 3 time Magnet® designated • Flagship of Carilion Clinic, a 7 hospital system • Region’s only Level 1 Trauma Center • 703-bed academic medical center • System-wide, serves nearly 1 million patients across Virginia, West Virginia and North Carolina Objectives At the conclusion of this education activity, the learner will be able to: • recall VTE risk factors and prevention • describe post-thrombotic syndrome and chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH) • identify nursing implications of caring for patients with post-thrombotic syndrome and CTEPH What is VTE? Pulmonary Embolus Deep Vein (PE) Thrombosis (DVT) Signs/Symptoms of DVT • Swelling • Erythema • Pain • Warmth1 Signs/Symptoms of PE 1 • Sudden onset of dyspnea • Tachycardia • Irregular heartbeat • Chest pain, worse with deep breath • Hemoptysis • Low blood pressure, light-headedness or syncope • 350,000 – 900,000 people per year are affected by VTE1, 2 • VTE is the leading cause of preventable hospital death in the US2 • VTE can occur without symptoms (silent)3 Quick Facts • Patients with DVT who are untreated have a 37% incidence of PE that is fatal4 • Combined mortality from PE (initial and recurrence) is 73%4 Quick Facts • 1 in 20 hospitalized patients will suffer a fatal PE if they have not received adequate VTE prophylaxis5 • For 25% of patients with PE, the first -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 9,498,481 B2 Rao Et Al

USOO9498481 B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 9,498,481 B2 Rao et al. (45) Date of Patent: *Nov. 22, 2016 (54) CYCLOPROPYL MODULATORS OF P2Y12 WO WO95/26325 10, 1995 RECEPTOR WO WO99/O5142 2, 1999 WO WOOO/34283 6, 2000 WO WO O1/92262 12/2001 (71) Applicant: Apharaceuticals. Inc., La WO WO O1/922.63 12/2001 olla, CA (US) WO WO 2011/O17108 2, 2011 (72) Inventors: Tadimeti Rao, San Diego, CA (US); Chengzhi Zhang, San Diego, CA (US) OTHER PUBLICATIONS Drugs of the Future 32(10), 845-853 (2007).* (73) Assignee: Auspex Pharmaceuticals, Inc., LaJolla, Tantry et al. in Expert Opin. Invest. Drugs (2007) 16(2):225-229.* CA (US) Wallentin et al. in the New England Journal of Medicine, 361 (11), 1045-1057 (2009).* (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this Husted et al. in The European Heart Journal 27, 1038-1047 (2006).* patent is extended or adjusted under 35 Auspex in www.businesswire.com/news/home/20081023005201/ U.S.C. 154(b) by Od en/Auspex-Pharmaceuticals-Announces-Positive-Results-Clinical M YW- (b) by ayS. Study (published: Oct. 23, 2008).* This patent is Subject to a terminal dis- Concert In www.concertpharma. com/news/ claimer ConcertPresentsPreclinicalResultsNAMS.htm (published: Sep. 25. 2008).* Concert2 in Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 6(6), 782 (2008).* (21) Appl. No.: 14/977,056 Springthorpe et al. in Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters 17. 6013-6018 (2007).* (22) Filed: Dec. 21, 2015 Leis et al. in Current Organic Chemistry 2, 131-144 (1998).* Angiolillo et al., Pharmacology of emerging novel platelet inhibi (65) Prior Publication Data tors, American Heart Journal, 2008, 156(2) Supp. -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2006/0110428A1 De Juan Et Al

US 200601 10428A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2006/0110428A1 de Juan et al. (43) Pub. Date: May 25, 2006 (54) METHODS AND DEVICES FOR THE Publication Classification TREATMENT OF OCULAR CONDITIONS (51) Int. Cl. (76) Inventors: Eugene de Juan, LaCanada, CA (US); A6F 2/00 (2006.01) Signe E. Varner, Los Angeles, CA (52) U.S. Cl. .............................................................. 424/427 (US); Laurie R. Lawin, New Brighton, MN (US) (57) ABSTRACT Correspondence Address: Featured is a method for instilling one or more bioactive SCOTT PRIBNOW agents into ocular tissue within an eye of a patient for the Kagan Binder, PLLC treatment of an ocular condition, the method comprising Suite 200 concurrently using at least two of the following bioactive 221 Main Street North agent delivery methods (A)-(C): Stillwater, MN 55082 (US) (A) implanting a Sustained release delivery device com (21) Appl. No.: 11/175,850 prising one or more bioactive agents in a posterior region of the eye so that it delivers the one or more (22) Filed: Jul. 5, 2005 bioactive agents into the vitreous humor of the eye; (B) instilling (e.g., injecting or implanting) one or more Related U.S. Application Data bioactive agents Subretinally; and (60) Provisional application No. 60/585,236, filed on Jul. (C) instilling (e.g., injecting or delivering by ocular ion 2, 2004. Provisional application No. 60/669,701, filed tophoresis) one or more bioactive agents into the Vit on Apr. 8, 2005. reous humor of the eye. Patent Application Publication May 25, 2006 Sheet 1 of 22 US 2006/0110428A1 R 2 2 C.6 Fig. -

Role of Thrombin and Thromboxane A2 in Reocclusion Following Coronary

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 86, pp. 7585-7589, October 1989 Medical Sciences Role of thrombin and thromboxane A2 in reocclusion following coronary thrombolysis with tissue-type plasminogen activator (thrombolytic therapy/coronary thrombosis/platelet activation/reperfusion) DESMOND J. FITZGERALD*I* AND GARRET A. FITZGERALD* Divisions of *Clinical Pharmacology and tCardiology, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN 37232 Communicated by Philip Needleman, June 28, 1989 (receivedfor review April 12, 1989) ABSTRACT Reocclusion of the coronary artery occurs against the prothrombinase formed on the platelet surface after thrombolytic therapy of acute myocardlal infarction (13) and the neutralization ofheparin by platelet factor 4 (14) despite routine use of the anticoagulant heparin. However, and thrombospondin (15), proteins released by activated heparin is inhibited by platelet activation, which is greatly platelets. enhanced in this setting. Consequently, it is unclear whether To address the role of thrombin during coronary throm- thrombin induces acute reocclusion. To address this possibility, bolysis, we have examined the effect of a specific thrombin we examined the effect of argatroban {MCI9038, (2R,4R)- inhibitor, argatroban {MCI9038, (2R,4R)-4-methyl-1-[N-(3- 4-methyl-l-[Na-(3-methyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-8-quinolinesulfo- methyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-8-quinolinesulfonyl)-L-arginyl]-2- nyl)-L-arginyl]-2-piperidinecarboxylic acid}, a specific throm- piperidinecarboxylic acid} on the response to tissue plasmin- bin inhibitor, on the response to tissue-type plasminogen ogen activator (t-PA) in a closed-chest canine model of activator in a dosed-chest canine model of coronary thrombo- coronary thrombosis. MCI9038, an argimine derivative which sis. MCI9038 prolonged the thrombin time and shortened the binds to a hydrophobic pocket close to the active site of time to reperfusion (28 + 2 min vs. -

Characterising the Risk of Major Bleeding in Patients With

EU PE&PV Research Network under the Framework Service Contract (nr. EMA/2015/27/PH) Study Protocol Characterising the risk of major bleeding in patients with Non-Valvular Atrial Fibrillation: non-interventional study of patients taking Direct Oral Anticoagulants in the EU Version 3.0 1 June 2018 EU PAS Register No: 16014 EMA/2015/27/PH EUPAS16014 Version 3.0 1 June 2018 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Title ........................................................................................................................................... 5 2 Marketing authorization holder ................................................................................................. 5 3 Responsible parties ................................................................................................................... 5 4 Abstract ..................................................................................................................................... 6 5 Amendments and updates ......................................................................................................... 7 6 Milestones ................................................................................................................................. 8 7 Rationale and background ......................................................................................................... 9 8 Research question and objectives .............................................................................................. 9 9 Research methods .................................................................................................................... -

Stroke Prevention in Chronic Kidney Disease Disclosures

5/18/2020 Controversies: Stroke Prevention in Chronic Kidney Disease Wei Ling Lau, MD FASN FAHA FACP Assistant Professor, Nephrology University of California, Irvine Visiting Fellow at OptumLabsCOPY Disclosures • Prior or current research funding from NIH, AHA, Sanofi, ZS Pharma, and Hub Therapeutics. • Associate Medical Director for home peritoneal dialysis at Fresenius University Dialysis Center of Orange. • Has beenNOT on Fresenius medical advisory board for Velphoro. • No conflicts of interest relevant to the current talk. Controversies: Stroke prevention in CKD Wei Ling Lau, MD DO 1 5/18/2020 Stroke Prevention in CKD • Blood pressure targets • Antiplatelet agents • Statins • Anticoagulation Controversies: Stroke prevention in CKD Wei Ling Lau, MD COPY BP TARGETS Data is limited, as patients with CKD were historically excluded from clinical trials NOT Whelton 2017 ACC/AHA hypertension guidelines [Hypertension 2018] Controversies: Stroke prevention in CKD Wei Ling Lau, MD DO 2 5/18/2020 Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial SPRINT: BP lowering to <120 vs <140 mmHg significantly lowered rate of CVD composite primary outcome; no clear effect on stroke Controversies: Stroke prevention in CKD The SPRINT Research Group. N Engl J Med 2015 p2103 Wei Ling Lau, MD COPY SPRINT subgroup analysis: CKD • Patients with CKD stage 3‐4 (eGFR of 20 to <60) comprised 28% of the SPRINT study population • Intensive BP management seemed to provide the same benefits for reduction in the CVD composite primary outcomeNOT – but did not impact stroke Controversies: Stroke prevention in CKD Cheung 2017 J Am Soc Nephrol p2812 Wei Ling Lau, MD DO 3 5/18/2020 The hazard of incident stroke associated with systolic BP (SBP) and chronic kidney disease (CKD)BP using and an unadjusted stroke model risk: that contained J‐shaped dummy variables association for CKD and BP groups (A) and a fully adjusted model that contained dummy variables for CKD and BP grou.. -

18512582.Pdf

European Heart Journal (2001) 22, 1938–1947 doi:10.1053/euhj.2001.2627, available online at http://www.idealibrary.com on The TRAPIST Study A multicentre randomized placebo controlled clinical trial of trapidil for prevention of restenosis after coronary stenting, measured by 3-D intravascular ultrasound P. W. Serruys1, D. P. Foley1, M. Pieper2, J. A. Kleijne3 and P. J. de Feyter1 on behalf of the TRAPIST investigators 1Department of Interventional Cardiology, Thoraxcenter, Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, The Netherlands; 2Heartcenter Bodensee, Kreuzlingen, Switzerland; and 3Cardialysis, Rotterdam, The Netherlands Background Studies have reported benefit of oral therapy significant difference between trapidil and placebo-treated with the phosphodiesterase inhibitor, trapidil, in reducing patients regarding in-stent neointimal volume (108·6 restenosis after coronary angioplasty. Coronary stenting is 95·6 mm3 vs 93·379·1 mm3; P=0·16) or % obstruction associated with improved late outcome compared with volume (3818% vs 3621%; P=0·32), in angiographic balloon angioplasty, but significant neointimal hyperplasia minimal luminal diameter at follow-up (1·630·61 mm vs still occurs in a considerable proportion of patients. The 1·740·69 mm; P=0·17), restenosis rate (31% vs 24%; aim of this study was to investigate the safety and efficacy P=0·24), cumulative incidence of major adverse cardiac of trapidil 200 mg in preventing in-stent restenosis. events at 7 months (22% vs 20%; P=0·71) or anginal complaints (30% vs 24%; P=0·29). Methods Patients with a single native coronary lesion requiring revascularization were randomized to placebo or Conclusion Oral trapidil 600 mg daily for 6 months did trapidil at least 1 h before, and continuing for 6 months not reduce in-stent hyperplasia or improve clinical outcome after, successful implantation of a coronary Wallstent. -

Toward an in Vitro Bioequivalence Test

TOWARD AN IN VITRO BIOEQUIVALENCE TEST by Jie Sheng A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Pharmaceutical Sciences) In The University of Michigan 2007 Doctoral Committee: Professor Gordon L. Amidon, Chair Professor Henry Y. Wang Associate Professor Nair Rodriguez-Hornedo Associate Professor Steven P. Schwendeman Jie Sheng © 2007 All Rights Reserved To Kurt Q. Zhu, my husband and my very best friend, and to Diana S. Zhu and Brandon D. Zhu, my lovely children. ii Acknowledgements Most of all, I thank Prof. Gordon L. Amidon, for his support, guidance, and inspiration during my graduate studies at the University of Michigan. Being his student is the best step happened in my career. I am always amazed by his vision, energy, patience and dedication to the research and his students. He trained me to grow as a scientist and as a person. I also wish to thank all of my committee members, Professors David Fleisher, Nair Rodriguez-Hornedo, Steven Schwendeman and Henry Wang, for their very insightful and constructive suggestions to my research. It took all their efforts to raise me as a professional scientist in pharmaceutical field. They all contributed significantly to development and improvement of my graduate work. Especially, Prof. Wang has also guided me in thinking of career development as if 20-year later. I felt to be his student in many ways. I thank mentors, colleagues and friends, Prof. John Yu from Ohio State University, Paul Sirois from Eli Lilly, Kurt Seefeldt, Chet Provoda, Jonathan Miller, John Chung, Chris Landoswki, Haili Ping and Yasuhiro Tsume from College of Pharmacy, for many interesting discussions throughout the graduate program. -

CDK4/6 Inhibitors in Breast Cancer Treatment: Potential Interactions with Drug, Gene and Pathophysiological Conditions

Review CDK4/6 Inhibitors in Breast Cancer Treatment: Potential Interactions with Drug, Gene and Pathophysiological Conditions Rossana Roncato 1,*,†, Jacopo Angelini 2,†, Arianna Pani 2,3,†, Erika Cecchin 1, Andrea Sartore-Bianchi 2,4, Salvatore Siena 2,4, Elena De Mattia 1, Francesco Scaglione 2,3,‡ and Giuseppe Toffoli 1,‡ 1 1 Experimental and Clinical Pharmacology Unit, Centro di Riferimento Oncologico (CRO), IRCCS, 33081 Aviano, Italy; [email protected] (E.C.); [email protected] (E.D.M.); [email protected] (G.T.) 2 Department of Oncology and Hemato-Oncology, Università degli Studi di Milano, 20122 Milan, Italy; [email protected] (J.A.); [email protected] (A.P.); [email protected] (A.S-B.); [email protected] (S.S.); [email protected] (F.S.) 3 Clinical Pharmacology Unit, ASST Grande Ospedale Metropolitano Niguarda, Piazza dell'Ospedale Maggiore 3, 20162 Milan, Italy 4 Department of Hematology and Oncology, Niguarda Cancer Center, Grande Ospedale Metropolitano Niguarda, 20162 Milan, Italy * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.:+390434659130 † These authors contributed equally. ‡ These authors share senior authorship. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, x; doi: www.mdpi.com/journal/ijms Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, x 2 of 8 Table S1. Co-administered agents categorized according to their potential risk for Drug-Drug interaction (DDI) in combination with CDK4/6 inhibitors (CDKis). Colors suggest the risk of DDI with CDKis: green, low risk DDI; orange, moderate risk DDI; red, high risk DDI. ADME, absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion; GI, Gastrointestinal; TdP, Torsades de Pointes; NTI, narrow therapeutic index. * Cardiological toxicity should be considered especially for ribociclib due to the QT prolongation. -

GTH 2021 State of the Art—Cardiac Surgery: the Perioperative Management of Heparin-Induced Thrombocytopenia in Cardiac Surgery

Review Article 59 GTH 2021 State of the Art—Cardiac Surgery: The Perioperative Management of Heparin-Induced Thrombocytopenia in Cardiac Surgery Laura Ranta1 Emmanuelle Scala1 1 Department of Anesthesiology, Cardiothoracic and Vascular Address for correspondence Emmanuelle Scala, MD, Centre Anesthesia, Lausanne University Hospital (CHUV), Lausanne, Hospitalier Universitaire Vaudois, Rue du Bugnon 46, BH 05/300, 1011 Switzerland Lausanne, Suisse, Switzerland (e-mail: [email protected]). Hämostaseologie 2021;41:59–62. Abstract Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) is a severe, immune-mediated, adverse drug Keywords reaction that paradoxically induces a prothrombotic state. Particularly in the setting of ► Heparin-induced cardiac surgery, where full anticoagulation is required during cardiopulmonary bypass, thrombocytopenia the management of HIT can be highly challenging, and requires a multidisciplinary ► cardiac surgery approach. In this short review, the different perioperative strategies to run cardiopul- ► state of the art monary bypass will be summarized. Introduction genicity of the antibodies and is diagnostic for HIT. The administration of heparin to a patient with circulating Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) is a severe, im- pathogenic HITabs puts the patient at immediate risk of mune-mediated, adverse drug reaction that paradoxically severe thrombotic complications. induces a prothrombotic state.1,2 Particularly in the setting The time course of HIT can be divided into four distinct of cardiac surgery, where full anticoagulation is required phases.6 Acute HIT is characterized by thrombocytopenia during cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB), the management of and/or thrombosis, the presence of HITabs, and confirma- HIT can be highly challenging, and requires a multidisciplin- tion of their platelet activating capacity by a functional ary approach. -

Trapidil Inhibits Human Mesangiai Cell Proliferation: Effect on PDGF Β

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Kidney International, Vol. 46 (1994), pp. 1002—1009 Trapidil inhibits human mesangial cell proliferation: Effect on PDGF a-receptor binding and expression LORETO GESUALDO, SALVATORE Di PAOLO, ELENA RANIERI, and FRANCESCO PAOLO SCHENA, with the technical assistance of ANNALISA BRUNACCINI Chair and Division of Nephrology, University of Bad, Ban, Italy Trapidil inhibits human mesangial cell proliferation: Effect on PDCF mediate, at least in part, the biological effect of other growth a-receptor binding and expression. Mesangial cell (MC) proliferation, a factors, as demonstrated for EGF, and elects PDGF as a potential histopathologic feature common to many human glomerular diseases, is regulated by several growth factors through their binding to specific cell autocrine regulator of MC proliferation [14]. surface receptors. Platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) is a peptide MC play a pivotal role in the course of glomerular injury: they exerting a potent mitogenic activity on MC. Recently, an increasedfirst act as target cells for several mediators, which are released expression of both PDGF protein and its receptor has been localized in locally or are delivered through the systemic circulation [4, 15, 16]. the mesangial areas of several experimental as well as human proliferative Thereafter, they may drive the evolution of pathologic lesions glomerulonephritides (GN). Thus, it may be postulated that the inhibition of PDGF action could prevent MC proliferation during mesangial prolif- towards resolution or progression of the glomerular disease. MC erative GN. Trapidil, an antiplatelet drug, has been shown to inhibit the proliferation, a histopatologic feature common to different forms growth of several cell types both in vitro and in vivo.