Forced Migration of Alaskan Indigenous Communities Due to Climate Change: Creating a Human Rights Response

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Climate Divisions for Alaska Based on Objective Methods Peter A

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Drought Mitigation Center Faculty Publications Drought -- National Drought Mitigation Center 2012 Climate Divisions for Alaska Based on Objective Methods Peter A. Bieniek University of Alaska Fairbanks, [email protected] Uma S. Bhatt University of Alaska Fairbanks Richard L. Thoman NOAA/National Weather Service/Weather Forecast Officea F irbanks Heather Angeloff University of Alaska Fairbanks James Partain NOAA/National Weather Service/Alaska Region See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/droughtfacpub Part of the Climate Commons, Environmental Indicators and Impact Assessment Commons, Environmental Monitoring Commons, Hydrology Commons, Other Earth Sciences Commons, and the Water Resource Management Commons Bieniek, Peter A.; Bhatt, Uma S.; Thoman, Richard L.; Angeloff, Heather; Partain, James; Papineau, John; Fritsch, Frederick; Holloway, Eric; Walsh, John E.; Daly, Christopher; Shulski, Martha; Hufford, Gary; Hill, David F.; Calos, Stavros; and Gens, Rudiger, "Climate Divisions for Alaska Based on Objective Methods" (2012). Drought Mitigation Center Faculty Publications. 15. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/droughtfacpub/15 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Drought -- National Drought Mitigation Center at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Drought Mitigation Center Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator -

Climate Change Impacts in Anchorage

MARCH 2016 STRENGTHENING RESILIENCE CLIMATE CHANGE IMPACTS IN ANCHORAGE Located in Southcentral Alaska, Anchorage is the most losses from extreme events, and threats to the health and populated area of the state and its economic hub, home safety of their employees. The business community in to about 300,000 people, or about half of the state’s resi- Anchorage can work together with city and state agen- dents.1 Energy production is the main driver of the state’s cies, along with other stakeholders to evaluate potential economy, although minerals, seafood, tourism, and agri- risks and take steps toward enhancing the community’s culture also contribute. Many oil and gas companies are resilience. headquartered in Anchorage.2 Anchorage is the state’s primary transportation, communications, trade, service, TEMPERATURE and finance center. The local economy is driven mostly by oil and gas, the military, transportation, and the tour- As a state, Alaska has warmed at more than twice the rate ism industry. The Port of Anchorage serves as the state’s of the rest of the United States, with state-wide average shipping hub. annual temperature increasing by 3°F and average winter temperature increasing by 6°F over the past 60 years.4 Anchorage is a diverse community, with minority groups representing 34 percent of its population and Temperature changes in Anchorage have been similar showing significant growth in these groups (including to the statewide average, with average annual tempera- Asian, Hawaiian, Pacific Islander, Native groups, African ture increasing by 3.2°F and winter temperatures increas- American, and other races). -

MONTHLY WEATHER REVIEW Editor, ALFRED J

MONTHLY WEATHER REVIEW Editor, ALFRED J. HENRY ~ ____~~~~ ~ . ~ __ VOL. 58,No. 3 1930 CLOSEDMAY 3, 1930 W. B. No. 1012 MARCH, ISSUED MAY31, 1930 ____ THE CLIMATES OF ALASKA By EDITHM. FITTON [C‘lark University School of Geography] CONTENTS for Sitka, the Russian capital. Other nations, chiefly Introduction_____---_---------------------------------. the English and Americans, early sent ships of espIoration I. Factirs controlling Alaskan climates- - - - - -.-. - :g into Alaskan waters, and there are ecatt.ered meteoro- 11. Climatic elements- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - ST logical records available for various points where these Sunshine, cloudiness, and fog-- -_--__-----__--- 87 vessels winte,red along Alaskan shores (7, P. 137). Temperature- - - - - __ _____ - - - - - - - - - _____ - _____ 59 Alter the United States purchased Alaska, the United Length of frostless season.. - - - - - - - - - __ - - - - -.- - - States Army surgeons kept weather records in connection Winds and pressure _____._____________________:: January and July _-___-----.--________________91 with the post hospitals. “In 1878 and 1579, soon after Precipitation - - - -.- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 93 the orga,nization of the United Stat,e,s Weather Bureau, SnowfaU_____________________~_________-_____96 first under the Signal Corps of t’heArmy, later as a’bureau Days with precipitatioil- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 111. Seasonal conditions in the cliniatic provinces-_ - - - - 9”; of the nePartlne11t of &Ticulture, a feltrfirst-class observ- I A. Pacific coast and islsnds (marine) - - - - -_- - - - 98 ing stations, together mth several volunt,ary stations of I B. Pacific coast and islands (rain shadow)------ 99 lamer order, were established in Masl<a” (1, p, 133). 11. Bering Sea coast and islands (semi-ice marine) - 99 1917 appropriationof $l~,~~operlilit,ted the estab- 111. Arctic coast (ice-marine) - - - - - - - - - - - - - __ - - - an IV. -

A Century of Climate Change for Fairbanks, Alaska Gerd Wendler University of Alaska, Fairbanks, [email protected]

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Papers in Natural Resources Natural Resources, School of 2009 A Century of Climate Change for Fairbanks, Alaska Gerd Wendler University of Alaska, Fairbanks, [email protected] Martha Shulski University of Nebraska–Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/natrespapers Part of the Climate Commons, Environmental Indicators and Impact Assessment Commons, Environmental Monitoring Commons, Meteorology Commons, Natural Resources and Conservation Commons, Natural Resources Management and Policy Commons, and the Other Environmental Sciences Commons Wendler, Gerd and Shulski, Martha, "A Century of Climate Change for Fairbanks, Alaska" (2009). Papers in Natural Resources. 563. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/natrespapers/563 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Natural Resources, School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Papers in Natural Resources by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. ARCTIC VOL. 62, NO. 3 (SEPTEMBER 2009) P. 295-300 A Century of Climate Change for Fairbanks, Alaska GERD WENDLER1'2 and MARTHA SHULSKI1 (Received 16 June 2008; accepted in revised form 21 November 2008) ABSTRACT. Climatological observations are available for Fairbanks, Interior Alaska, for up to 100 years. This is a unique data set for Alaska, insofar as it is of relatively high quality and without major breaks. Applying the best linear fit, we conclude that the mean annual temperature rose from -3.6°C to -2.2°C over the century, an increase of 1.4°C (compared to 0.8°C worldwide). -

2018 Alaska Climate Summary

Alaska Climate Research Center Geophysical Institute, University of Alaska Annual Report for 2018 prepared for The American Association of State Climatologists The Alaska Climate Research Center (ACRC) is part of the Geophysical Institute, University of Alaska Fairbanks. Historically, the ACRC has shared tasks with the Alaska State Climate Center, and we are excited to report that both centers are currently in the process to merge. The main tasks and objectives of the Alaska State Climate Center have been renewed within the 2018 Alaska State Statutes via Title 14, Chapter 40, Section 085. Specific information can be found about this statute at http://www.legis.state.ak.us/basis/statutes.asp#14.40.085. Funding support for the ACRC comes from the Geophysical Institute and externally funded research projects. Key Personnel: Martin Stuefer, Director ACRC, Research Associate Professor Lea Hartl, Post Doctoral Researcher ACRC Jason Grimes, Research Technician ACRC Gerd Wendler, previous Director, ACRC, Professor Emeritus Blake Moore, Programmer Telayna Gordon, Research Technician Purpose: The purpose of the center is threefold: • Dissemination of climatological information and data. • Research on climate variability and climate change in Alaska and Polar Regions, and • Education and engagement with our stakeholders. Dissemination: For nearly three decades we have made climatological data available to the public, private, and government agencies, and to researchers around the world. Over the course of a year, winter is the busiest season for public inquiries to the Alaska Climate Research Center, probably due to the very cold temperatures (down to -40°F and colder) and ice fog, which makes driving difficult, if not dangerous. -

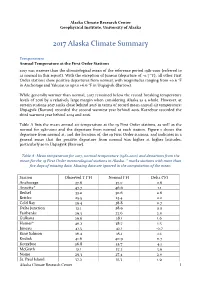

2017 Alaska Climate Summary

Alaska Climate Research Center Geophysical Institute, University of Alaska 2017 Alaska Climate Summary Temperature Annual Temperature at the First Order Stations 2017 was warmer than the climatological mean of the reference period 1981-2010 (referred to as normal in this report). With the exception of Juneau (departure of -0.7 °F), all other First Order stations show positive departures from normal, with magnitudes ranging from +0.6 °F in Anchorage and Yakutat to up to +6.6 °F in Utqiaġvik (Barrow). While generally warmer than normal, 2017 remained below the record breaking temperature levels of 2016 by a relatively large margin when considering Alaska as a whole. However, at certain stations 2017 ranks close behind 2016 in terms of record mean annual air temperature: Utqiaġvik (Barrow) recorded the second warmest year behind 2016. Kotzebue recorded the third warmest year behind 2014 and 2016. Table A lists the mean annual air temperature at the 19 First Order stations, as well as the normal for 1981-2010 and the departure from normal at each station. Figure 1 shows the departure from normal at, and the location of, the 19 First Order stations, and indicates in a general sense that the positive departure from normal was higher at higher latitudes, particularly so in Utqiaġvik (Barrow). Table A: Mean temperature for 2017, normal temperature (1981-2010) and deviations from the mean for the 19 First Order meteorological stations in Alaska. * marks stations with more than five days of missing data. Missing data are ignored in the computation of the mean. Station Observed T (°F) Normal (°F) Delta (°F) Anchorage 37.6 37.0 0.6 Annette* 47.7 46.6 1.1 Bethel 33.2 30.6 2.6 Bettles 25.5 23.4 2.2 Cold Bay 39.4 38.8 0.7 Delta Junction 31.1 28.9 2.2 Fairbanks 29.5 27.6 2.0 Gulkana 29.6 28.1 1.6 Homer* 40.2 38.7 1.5 Juneau 41.3 42.1 -0.7 King Salmon 36.4 35.1 1.3 Kodiak 41.6 40.9 0.7 Kotzebue 26.8 22.7 4.1 McGrath 31.1 27.2 3.9 Nome 29.3 27.4 2.0 St. -

Wildlife Response to Environmental Arctic Change

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Wildlife Response to Environmental Arctic Change Predicting Future Habitats of Arctic Alaska Workshop Sponsors University of Alaska Fairbanks (UAF) International Arctic Research Center ABR Inc. UAF Institute of Arctic Biology Wildlife Conservation Society Workshop and Report Coordination The Arctic Research Consortium of the U.S. (ARCUS) coordinated workshop planning and implementation, and report layout and editing. rctic Res l A ea a r n c o h i t C a e n r n t e e t r n I U s k n n iv a er rb sity ai of Alaska F Workshop Speakers David Atkinson, Erik Beever, Eugenie Euskirchen, Brad Griffith, Geoffrey Haskett, Larry Hinzman, Torre Jorgenson, Doug Kane, Peter Larsen, Anna Liljedahl, Vladimir Romanovsky, Martha Shulski, Matthew Sturm, Amy Tidwell, and Mark Wipfli. Report Reviewers Brian Lawhead, Anna Liljedahl, Wendy Loya, Neil Mochnacz, Larry Moulton, Stephen Murphy, Tom Paragi, Jim Reist, Vladimir Romanovsky, John Walsh, Matthew Whitman, and Steve Zack. Photo Contributors Doug Canfield, Stephanie Clemens, Bryan Collver, Fred DeCicco, Elizabeth Eubanks, Richard Flanders, Larry Hinzman, Marie-Luce Hubert, Benjamin Jones, M. Torre Jorgenson, Jean-Louis Klein, Catherine Moitoret, Mitch Osborne, Leslie Pierce, Jake Schaas, Ted Swem, Ken Tape, Øivind Tøien, Ken Whitten, Chuck Young, Steve Zack, and James Zelenak. Cover Image Ice floating in a lagoon near Collinson Point in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. Photo by Philip Martin. Suggested Citation Martin, Philip D., Jennifer L. Jenkins, F. Jeffrey Adams, M. Torre Jorgenson, Angela C. Matz, David C. Payer, Patricia E. Reynolds, Amy C. Tidwell, and James R. -

Synoptic Climatology of Extreme Snow and Avalanche Events in Southern Alaska Kristy C

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 2016 Synoptic Climatology Of Extreme Snow And Avalanche Events In Southern Alaska Kristy C. Carter University of South Carolina Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the Geography Commons Recommended Citation Carter, K. C.(2016). Synoptic Climatology Of Extreme Snow And Avalanche Events In Southern Alaska. (Master's thesis). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/3764 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SYNOPTIC CLIMATOLOGY OF EXTREME SNOW AND AVALANCHE EVENTS IN SOUTHERN ALASKA by Kristy C. Carter Bachelor of Science Iowa State University, 2013 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Science in Geography College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2016 Accepted by: Cary J. Mock, Director of Thesis April L. Hiscox, Reader Edsel A. Pena, Reader Lacy Ford, Senior Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies © Copyright by Kristy C. Carter, 2016 All Rights Reserved. ii DEDICATION I would like to dedicate this thesis to my late grandparents Dwayne and Marge Shoemaker. Without their initial support and encouragement, I would not have discovered the joy and excitement of studying meteorology at the undergraduate and now graduate level. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the members of my thesis committee for their support and encouragement, Dr. Cary Mock, Dr. April Hiscox and Dr. -

Climate-Induced Displacement of Alaska Native Communities

Climate-Induced Displacement of Alaska Native Communities January 30, 2013 Robin Bronen Alaskan Immigration Justice Project Cover image: Winifried K. Dallmann, Norwegian Polar Institute. http://www.arctic-council.org/index.php/en/about/maps. TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................... i Introduction ................................................................................................................................................... 1 An Overview of Climate Change in Alaska .................................................................................................. 1 The Impact of Climate Change on Alaska Native Rural Villages ................................................................ 4 Gradual Forced Displacement of Communities ............................................................................................ 9 Climate Risks in Eight Communities ...................................................................................................... 10 Communities Requiring Relocation in Their Entirety ............................................................................ 12 Government Response to Climate-Threatened Communities ..................................................................... 18 Conclusion .................................................................................................................................................. 19 References: ................................................................................................................................................. -

Alaska Climate Dispatch Sept 2015

WINTER 2015-16 BROUGHT TO YOU BY THE ALASKA CENTER FOR CLIMATE ASSESSMENT AND POLICY IN PARTNERSHIP WITH THE ALASKA CLIMATE RESEARCH CENTER, SEARCH SEA ICE OUTLOOK, NATIONAL CENTERS FOR ENVIRONMENTAL PREDICTION, AND THE NATIONAL WEATHER SERVICE THE NEW WINTER SEVERITY INDEX IN ALASKA By Brian Brettschneider, Borealis Scientific, LLC, Anchorage Analyses of a broad range of data relating to Alaska climate and weather are available on the Alaska Climate Info Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/AlaskaClimateFacts. The winter of 2015-16 in Alaska will be remembered as one of the mildest on Circumstances beyond our control made record. In fact, according to the newly developed Accumulated Winter Season it impossible to complete the Autumn and Severity Index (AWSSI), it was the least severe winter on record for many Winter 2015 issues of the Alaska Climate locations in Alaska (Figure 1). Dispatch on schedule. We apologize to our Before delving into this new winter severity index, let’s examine how we readers and hope they will enjoy this special describe the intensity, or lack thereof, of winter conditions. At the qualitative 3-season issue, which covers September level, we usually describe winter as being either cold or warm, and either snowy 2015 to May 2016. or not snowy. IN THIS ISSUE During the winter of 2015-16, air temperatures were substantially warmer than normal across the entire state, and snowfall was well below normal in Winter Severity Index ................pages 1-5 most, but not all, places (details pages 16-19). Rivers were slow to freeze up in Weather Impacts ....................................6-8 the fall, and many reported their earliest spring breakup on record—some by large margins. -

A Toolbox for Resilience and Adaptation in Coastal Arctic Alaska 2017 Guide for Alaska Communities, Tribes, Agencies and Citizens Strategies, Actions and Resources

A Toolbox for Resilience and Adaptation in Coastal Arctic Alaska 2017 Guide for Alaska Communities, Tribes, Agencies and Citizens Strategies, Actions and Resources Coast photo courtesy of Molly Mylius. King Salmon Workshop courtesy of Landscape Conservation Cooperatives. Contents Credits ........................................................................................................................................................... 7 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................. 9 Resilience .................................................................................................................................................... 9 Adaptation .................................................................................................................................................. 9 About this Guide ............................................................................................................................................ 10 Toolbox 1: Resilience and Adaptation Strategies ................................................................................. 11 Resilience and Adaptation in a Changing World ....................................................................................... 11 We all have the power to do something. .............................................................................................. 11 Leadership and Communication ............................................................................................................ -

THE FOREST ECOSYSTEM of SOUTHEAST ALASKA L.The Setting

1974 USDA FOREST SERVICE GENERAL TECHNICAL REPORT PNW-12 This file was created by scanning the printed publication. Text errors identified by the software have been corrected; however, some errors may remain. THE FOREST ECOSYSTEM OF SOUTHEAST ALASKA l.The Setting Arland S. Harris 0. Keith Hutchison William R. Meehan Douglas N. Swanston Austin E. Helmers John C. Hendee Thomas M. Collins PACIFIC NORTHWEST FOREST AND RANGE EXPERIMENT STATION U.S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE FOREST SERVICE PORTLAND, OREGON ABSTRACT A description-of the discovery and exploration of southeast Alaska sets the scene for a discussion of the physical and biological features of this region. Subjects discussed include geography, climate, vegetation types, geology, minerals, forest products, soils, fish, wildlife, water, recreation, and esthetic values. This is the first of a series of publications sumnarizing present knowledge of southeast Alaska's forest resources. Pub1 ications will follow which discuss in detail the subjects mentioned above and how this information can be helpful in managing the resources. Keywords: Forest surveys, Alaska, resource planning, researc h. CONTRIBUTORS FORESTRY SCIENCES LABORATORY , JUNEAU ALASKA Arland S. Harris, Vegetation 0. Keith Hutchison, Wood Industries William R. Meehan, Fish and Vildlife FORESTRY SCIENCES LABORATORY , CORVALLIS, OREGON Douglas N. Swanston, Geology INSTITUTE OF NORTHERN FORESTRY, FAIRBANKS , ALASKA Austin E. Helmers, Discovery and History, Geography, Water MILDLAND RECREATION PROJECT, SEATTLE, WASHINGTON John C. Hendee, Recreation and Esthetics ALASKA REGION, U .S. FOREST SERVICE, JUNEAU, ALASKA Thomas pi. Collins, Soizs and Soil Development PREFACE This, the first in a series of pub1 ications summarizing knowledge about the forest resources of southeast dlaska, describes the physical, biological, and socioeconomic setting of southeast Alaska.